|

|

Trong bài viết

có nhắc tới bà vợ của Hemingway, trên, mà theo tác giả, qua bạn bè của

bà, có

thể đã tự tử.

"I hope

you're not expecting lunch," she said rather sharply. She did bring me

a

glass of ice water, and had laid out a guest towel in her upstairs

bathroom for

me to use. But that was the limit of her hospitality and, by

implication, her

professional encouragement.

A few weeks later, I got a letter from her

scolding me for having made mistakes in my article. I had reported that

the

light in the room was strong, when in fact it had been rather weak.

What

infuriated her most was that I had mentioned she had once been

Hemingway's

wife. You violated the rule of journalism, she wrote. You lied.

Lapham's Winter

2013: Intoxication

“Vẫn là nó. Nhưng không phải là

nó!”

Câu trên là của ông Tổng Giám

Đốc Bưu Điện - và còn là một trong những ông Thầy

dạy Gấu, khi học trường Quốc Gia Bưu Điện - phán về sếp trực tiếp của

GCC, sau

khi ông ra khỏi bịnh viện và trở về Bưu Điện làm việc lại.

Ông bị mất khẩu súng, trong vụ mìn Mỹ Cảnh, GCC đã lèm bèm nhiều lần

rồi.

Sở dĩ

nhắc lại,

là vì trong cái “memoir” viết về cuộc vây hãm Sarajevo, có 1 anh chàng

phóng viên,

trở về lại Berlin, trở về lại căn phòng của mình, và, xỏ vô quần, và,

cái

quần tuột ra khỏi anh ta.

Thoạt đầu, anh ta nghĩ,

đếch phải quần của mình, nhưng

nhìn lại thì đúng là quần của mình. Và anh ngộ ra, mình thì vẫn là

mình, đếch mất

cái chó gì cả - tất nhiên, súng vưỡn còn – nhưng, một cách nào đó, về

thể chất

lẫn tinh thần, anh ta đếch còn như xưa!

Đúng là tình

cảnh của Gấu. Sau cú Mỹ Cảnh, tuy súng ống còn nguyên, nhưng có 1 cái

gì đã mất

đi, theo nó.

MEMOIR

LIFE DURING

WARTIME

Remembering

the siege of Sarajevo

By Janine di

Giovanni

There was

spring rain and pale fog in Sarajevo as my plane approached the city

last

April, veering over the green foothills of Mount Igman. Through the

frosted

window I could see the outline of the road we used to call Snipers'

Alley,

above which Serbian sharpshooters would perch and fire at anyone below.

Twenty

years had passed since I'd arrived in Sarajevo as a war reporter.

During the siege

of the city, most foreign journalists had lived in the Holiday Inn, and

it was

in that grotty hotel that the man who was to become my husband and the

father

of my child professed undying love. I met some of my best friends in

Sarajevo

and lost several others-to alcoholism, drugs, insanity, and suicide. My

own

sense of compassion and integrity, I think, was shaped during those

years.

Since then I

had come back many times to report on Bosnia, on the genocide there,

and to try

to find people who had gone missing during the war. Now I was returning

for a

peculiar sort of reunion that would bring together reporters,

photographers,

and aid workers who, for one reason or another, had never forgotten the

brutal

and protracted siege, which lasted nearly four years. By the end of the

war, in

1995, a city once renowned for its multiculturalism and industrial

vigor had

been reduced to medieval squalor.

Why was it

that Sarajevo, and not Rwanda or Congo or Sierra Leone or Chechnya-wars

that

all of us went on to report-captured us the way this war did? One of

us, I

think it was Christiane Amanpour, called it "our generation's

Vietnam." We were often accused of falling in love with Sarajevo

because

it was a European conflict-a war whose victims looked like us, who sat

in cafes

and loved Philip Roth and Susan Sontag. As reporters, we lived among

the people

of Sarajevo. We saw the West turn its back and felt helpless.

I had begun

my career in journalism covering the First Intifada in the late 1980s.

I came

to Sarajevo because I wanted to experience firsthand the effect war had

on

civilians. My father had taught me to stick up for under-dogs, to be on

the

right side of history. But I had no idea what it would feel like to

stare into

the open eyes of the recently dead; how to count bodies daily in a

morgue; how

to talk to a woman whose children had just been killed by shrapnel

while they

were building a snowman.

During my

first ride into the city from the airport-past a blasted wall on which

the

words WELCOME TO HELL had been grafittied-it was clear that my wish to

see war

up close would be granted. I had gotten a lift from a photographer

named Jon

Jones, and as we careened down Snipers' Alley toward the city, he told

me how

many reporters had already been killed, how close the snipers were and

how

easily they could see us, and about the hundreds of mortar shells that

fell on

Sarajevo each day. He recounted in detail how a CNN camerawoman had

been shot

in the jaw, and told me that a bullet could rip through the metal of a

car as

easily as a needle pierces a piece of cloth.

"Think

of being in a doll's house," he said, edging up to a hundred miles per

hour on the straightaways. "We're the tiny dolls."

He dropped

me off at the Holiday Inn, the only "functioning" hotel in the city,

leaving me to lug inside my flak jacket, battery-operated Tandy

computer,

sleeping bag, and a duffel bag filled with protein bars, antibiotics, a

flashlight, batteries, candles, waterproof matches, pens and notebooks,

and a

pair of silk long johns (which I never took off that entire first

winter of the

war). I had with me just a single book: a copy of The Face

of War, by Martha Gellhorn, a journalist who had covered

the Spanish Civil War, the Allies' invasion of Normandy, Vietnam, the

Six-Day

War, and almost every other major conflict of the twentieth century.

She

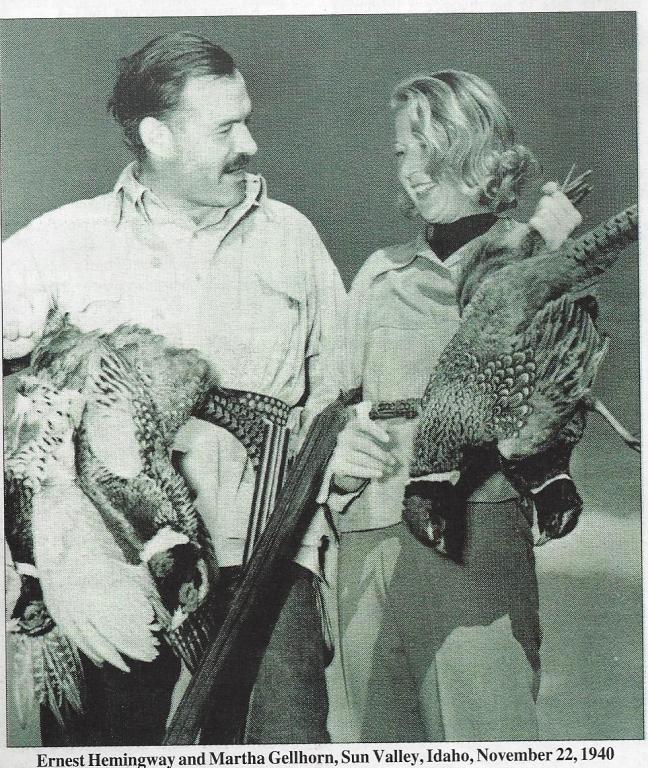

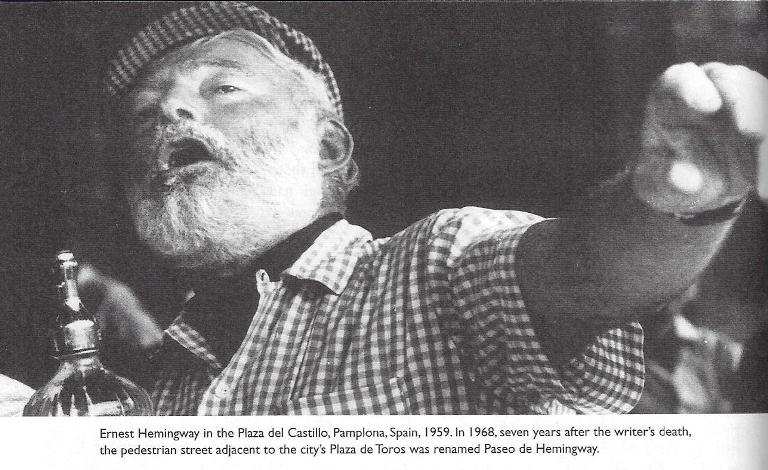

settled in Paris in 1930, married a Frenchman, and began to write for Collier's, The Saturday Evening Post,

and other publications. In 1936, in a bar in Key West (the Frenchman

was long

gone), she met Ernest Hemingway, whom she married, and later moved with

him to

Spain. She was blonde and beautiful and, above all, brave. She was

also, as I

would later find out, very ill-tempered and often not a "woman's

woman."

I had gone to meet Gellhorn in Wales on a hot summer

day in 1991,

having been sent to interview her about a collection of her novels that

was

just being published. History had forgotten her to some extent, but she

had a

loyal cadre, mostly men, who adored her. She drank and smoked, but she

had a

rare femininity.

That day, I

took a train, a bus, then finally hiked over hot fields to reach

Catscradle,

her remote cottage. I was keenly aware of my youth and inexperience,

and felt

embarrassed for all that I had not yet witnessed. She answered

the door in tailored slacks with a long cigarette in her hand. She was

in her

eighties by then and still extremely good-looking. She invited me

inside and

together we watched the invasion of Slovenia on television while she

made

astute comments about the coming destruction of Yugoslavia. I listened

intently, but, as she made clear, she had no interest in taking on a

protégée.

"I hope

you're not expecting lunch," she said rather sharply. She did bring me

a

glass of ice water, and had laid out a guest towel in her upstairs

bathroom for

me to use. But that was the limit of her hospitality and, by

implication, her

professional encouragement.

A few weeks

later, I got a letter from her scolding me for having made mistakes in

my

article. I had reported that the light in the room was strong, when in

fact it

had been rather weak. What infuriated her most was that I had mentioned

she had

once been Hemingway's wife. You violated the rule of journalism, she

wrote. You

lied.

Some years later, shortly before she died (her close

friends believed it

was suicide), we served together on a panel about war reporting for

Freedom

House, and she called me "dear girl," and embraced me affectionately.

By then, I had reported on many sieges and many wars. Someone took a

photograph

of us together, both speaking animatedly, our faces captured in heated

emotion.

*

In the lobby of the

Holiday Inn, I looked around and tried to be brave. To my

surprise, there was an ordinary, if dark, reception area with

cubbyholes for

passports presided over by a rather elegant bespectacled man who took

my

documents, registered them, and handed me the keys to a room on the

fourth

floor.

"There's

no elevator," he said matter-of-factly, "since there's no electricity.

Take the stairs there." He gestured toward a cavernous hallway and told

me

the hours of the communal meals, which were served in a makeshift

dining room

lit by candles.

''And please, madame, don't walk on this side of the

building." He pointed to a wall, through which you could see the sky

and

buildings outside, that looked as though a truck had run into it. ''And

don't

go up on the seventh floor," he added cryptically. The seventh floor, I

soon learned, was where the Bosnian snipers defending the city were

positioned.

And the forbidden side of the building faced the Serbian snipers and

mortar

emplacements. If you emerged from the hotel on that side and a sniper

had you

in his range, you got shot.

Walking into the dining room that first night, I

felt I had made a terrible mistake. I knew no one in Sarajevo, it was a

few

weeks before Christmas, and it was bitterly cold. I had not seen the

photographer since he'd dumped me at the hotel (declaring, in passing,

that he

hated all writers). Perhaps, I thought, staring at the blown-out

windows and

mortar-cracked walls, I should stay a few days and go home.

Around me, I heard

many languages: Dutch, Flemish, French, German, Japanese, Spanish, as

well as

Serbo-Croatian (which is now often referred to as three separate but

nearly

identical tongues: Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian). The huge room was

full of

grizzled reporters, everyone looking slightly dazed-a combination of

exhaustion, hang- over, and shock. In the distance I heard machine-gun

fire and

a mortar shell dropping somewhere in the city. No one paid attention to

the

noise, or to a newcomer like me.

But I soon encountered warmth and even fierce

camaraderie. Over dinner - a plate of rice and canned meat from a

humanitarian-aid box - an American cameraman of Armenian descent named

Yervant

Der Parthogh told me about the toilets. "Find an empty room and follow

your nose," he said, passing me a bottle of Tabasco sauce, standard

issue

in war zones, where the bland diet of rice cried out for a little

seasoning.

(ABC, the BBC, and other TV-news organizations bought the condiment in

bulk,

and it was often shared.)

What exactly did he mean about the toilets? Yervan

explained that certain rooms were always vacant, since their walls had

been

partially blown away, exposing the interior to sniper fire. But in the

attached

bathrooms, the toilets remained- unflushable, full, and stinking. "Find

one and make it your own," he advised.

The window

in my room had been destroyed by a rocket and replaced with plastic by

the

U.N.'s refugee agency. The shelling was continuous. I unpacked my gear,

propped

my flashlight against a cup, brushed my teeth with the mineral water I

had

brought from Zagreb, laid out the St. Jude medallion my mother had

given me,

and unrolled my sleeping bag on top of an orange polyester blanket left

over from

the glory days of 1984, when Sarajevo was an Olympic city and the

gruesome

Soviet-style structure of the Holiday Inn had been built.

As I discovered the

next day, the press corps consisted of a bunch of men with cameras or

notebooks

in a standard uniform: jeans, Timberland boots, and ugly zip-front

fluorescent fleeces.

The sole exception was a tall, thin Frenchman named Paul Marchand, a

radio

reporter, whose outfit consisted of a pressed white shirt, creased

black

trousers, and shiny dress shoes.

There were,

I was relieved to see, other women. I recognized Amanpour, young,

glamorous,

and more visible than ever after her coverage two years earlier of the

Gulf

War. I also encountered a few French female reporters, all of whom

violated the

masculine dress code: a reporter from Le

Parisien who wore cashmere sweaters; the petite radio reporter

Ariane

Quentier, who favored a Russian fur hat; and Alexandra Boulat, a

photographer

with a mane of long blond hair (she died after suffering a brain

aneurysm in Ramallah,

in 2007, at the age of forty-five).

I also met

Kurt Schork, who had a room near mine on the fourth floor. He was a

legendary

Reuters correspondent who had become a war reporter at the age of forty

after working

for New York City's Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Schork

brought me to the Reuters office and showed me how to file my copy on a

satellite phone for fifty dollars a minute. There was a generator in

the next

room, which reeked of gasoline, and if it was running, one dialed the

London

office, then read the copy to a distant, frenetic typist, spelling out

all the

Serbo-Croatian words. It was very World War II. Carrier pigeons would

have been

faster.

Over the

next few weeks, Schork patiently told me where and where not to go. He

showed

me how to rig up a hose as a kind of makeshift shower. On Christmas

Eve, we

went to midnight mass together at St. Josip's Catholic church on

Snipers' Alley

(though not at midnight, since that would have been an invitation to

the Serbs

to shell us); Christian soldiers, who made up perhaps a quarter of

Bosnia's

largely Muslim defense force, came down from the front line at the

outskirts of

the city to receive communion.

Room 437

would be my home, on and off, for the next three years: the mangy

orange

blanket, the plywood desk with cigarette burns, the empty minibar, the

telephone on the bedside table that never rang because the lines were

cut. And

through the plastic sheeting of my window, I had a view of the city,

with its

35,000 destroyed buildings and its courageous populace that refused to

bend to

its oppressors.

*

The 2012

reunion in Sarajevo was to take place over the first week of April,

Holy Week.

This had some resonance for me, since during the siege I often went to

mass

with other Catholic reporters in the battered Catholic church. It had

given me

solace, and seeing the old ladies bent over their rosary beads

reassured me in some

way that wherever I went in the world I could find a common community

bound by

religion.

Shortly

after I arrived for the reunion, I ran into Emma Daly, who had been a

reporter

for the British Independent during the war and now worked for Human

Rights Watch.

She had married the war photographer Santiago Lyon, now a senior AP

boss, and was

the mother of two children. In those days, I don't think either one of

us projected

much into the future or could have imagined ourselves married, with

children,

living more or less normal lives.

"Have

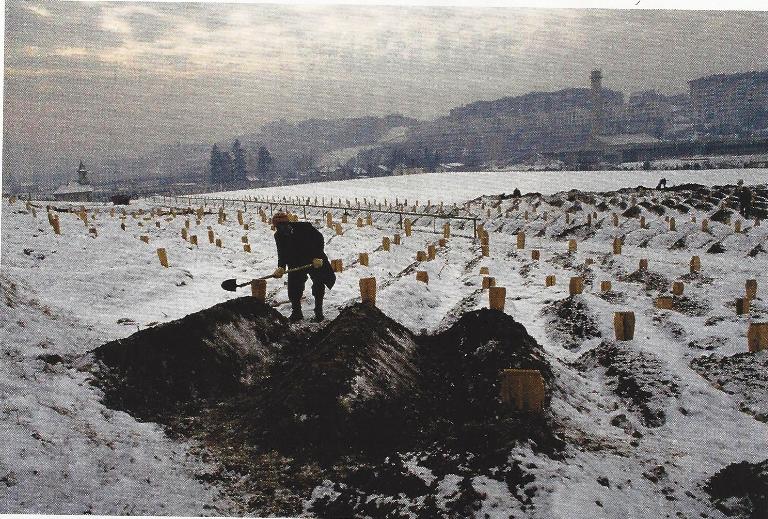

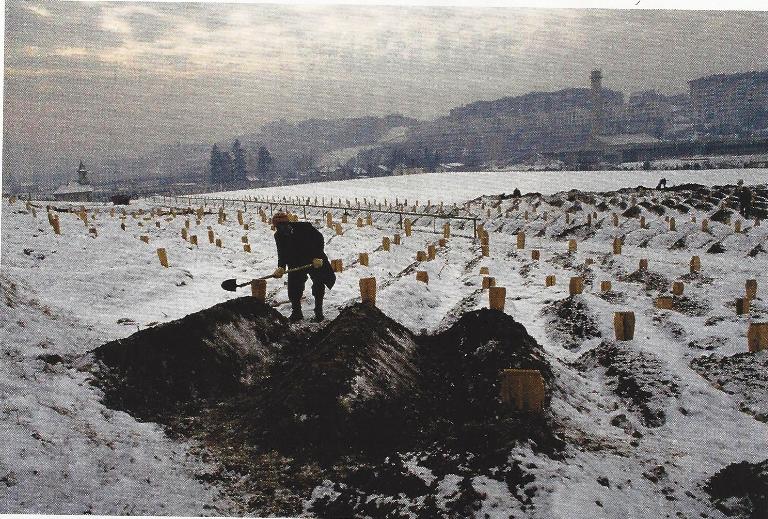

you seen the chairs yet?" she asked.

Emma explained that a kind of temporary

memorial had been set up on Marshal Tito Street, in the center of the

city:

11,541 empty red chairs, one for every resident killed during the

siege.

Walking downtown, we approached the Presidency Building, where we had

risked

sniper fire and stray mortar rounds during the war to interview

President Alija

Izetbegovic or Vice President Ejup Ganic, who always let journalists

into his

office and sometimes offered us hot coffee. "If you're brave enough to

come to this building," Ganic once told me, "then I am going to talk

to you."

The rows of red chairs, some of them scaled down to

represent

children, stretched far into the distance. Later there would be some

grumbling over

the fact that the chairs had been made in a Serbian factory. Yet the

amount of

destruction they represented was overwhelming-everyone of these people

might

still be alive if a sniper had failed to pull the trigger, if a mortar

shell

had landed twenty feet to the east or west.

That night,

at the refurbished Holiday Inn, we all got horribly drunk. Then we

started

taking group pictures. All of us were a little rounder in the face, the

men

with less hair and bigger bellies. The women, though, looked remarkably

good.

The

Holiday Inn now offers Wi-Fi, working toilets, a few restaurants (the

food

still bad), and clean sheets. We gathered in the bar, a group of

veteran

reporters and photographers who hadn't seen one another in twenty

years. There

was Morten Hvaal, a Norwegian photographer who once had driven me

around the

city in the AP's armored car, pointing out landmarks; Shane ("Shaney")

McDonald, an Australian cameraman who had sat in my room one night with

Keith

"Chuck" Tayman and Robbie Wright, watching falling stars from an open

window; and there, in a corner, Jon Jones, the photographer who had

scared me

so on my first ride from the airport. Now he was nice. We had all grown

up.

But

some people were missing from the Holiday Inn lounge where we had spent

years

living on whiskey, cigarettes, and chocolate bars. Shouldn't Kurt

Schork have

been sitting on a barstool, drinking a cranberry juice? Kurt was killed

by rebel

soldiers in Sierra Leone in May 2000, the morning after we ate dinner

together

in a restaurant overlooking the sea. And where was Paul Marchand, with

his

black shoes and white shirt? (He had once called me in the middle of

the night to

shout, "The water is running and she is hot!") After the war he wrote

novels, started drinking, and, one night in 2009, hanged himself. Juan

Carlos

Gumucio was gone, too. A bear of a man-and the second husband of Sunday Times reporter Marie Colvin, also

gone, killed in Homs, Syria, in February 2012-he had introduced himself

to me

in central Bosnia by exclaiming, "Call me JC! Like Jesus Christ. Or

like King

Juan Carlos." We used to go to Sunday mass together in Sarajevo- and in

London too, but then out afterward for bloody marys. In 2002 he shot

himself in

the heart after, in Colvin's words, "seeing too much war." I was in

Somalia at the time, on a hotel rooftop, and someone phoned to tell me.

There

were gunshots all around me, and over that din I began to cry for my

friend.

*

The morning

after our reunion, we all had hangovers. Gradually, we pulled ourselves

together, and shortly after noon, we went to a vineyard owned by a

local former

employee of the AP. There we spent the afternoon drinking wine and

looking out over

the hills at Sarajevo. It was almost unthinkable, but we were sipping

wine and

eating slow-cooked lamb in the exact spot where snipers had set up

twenty years

before.

Our return to our homes in Auckland,

Beirut, Boston, London, Milan, New York, Nicosia, Paris, and Vienna was

followed by a flurry of comradely emails and pictures posted on

Facebook. There

was much talk of getting together again, which we all knew would never

happen.

Then we all plunged into depression. A few days later I received a

letter from

Edward Serotta, who had gone to Sarajevo to document its Jewish

population

during the Bosnian war and now works in Vienna reconstructing family

histories

that were lost during the Holocaust. Serotta said that he remembered

coming

back to his Berlin apartment after weeks in Sarajevo and putting on a

pair of

trousers that slid off him. At first he thought they belonged to

someone else. Then

he realized that they were his-and that he was still himself- but

physically

and emotionally, he was not the same person who first went to Sarajevo.

Serotta

told me he remembered a night he walked through the city, in November

1993,

thinking, "If mankind is going to destroy itself, I feel honored and

privileged to be here to see how it is done."

After I put

his letter away, I gathered up all my Sarajevo mementos - the tiny bits

of

shrapnel, a photograph of me and Ariane in helmets on the front line, a

copper

coffee pot, a love note that Bruno, my husband, had left me in Room 437

after

our first meeting, his English then imperfect: "I won't loose you."

*

At the

airport, a group of us had gathered for coffee: Serotta; the Pulitzer

Prize-winning journalist Roy Gutman; Ariane; Peter Kessler (a U.N.

refugee

worker) and his wife, Lisa; and Anna Cataldi, an Italian writer and

U.N.

ambassador. Ariane and I soon boarded the plane to Paris, and

she-always the

astute little reporter in the fur hat-caught my mood.

"Don't

be sad," she said. "There are many places to go." She fiddled

with her handbag and read Paris Match.

But I was sad. My experience in Sarajevo was the last time I thought I

could

change something. The city was passing below my eyes from the plane

window,

forever broken, resting on a long flowing river. _

(1) Janine

di Giovanni has won four major awards for her war reporting and is a

member of

the Council on Foreign Relations. She is currently writing a book about

Syria,

to be published by Norton. She lives in Paris.

HARPER'S

MAGAZINE / APRIL 2013

|

|