|

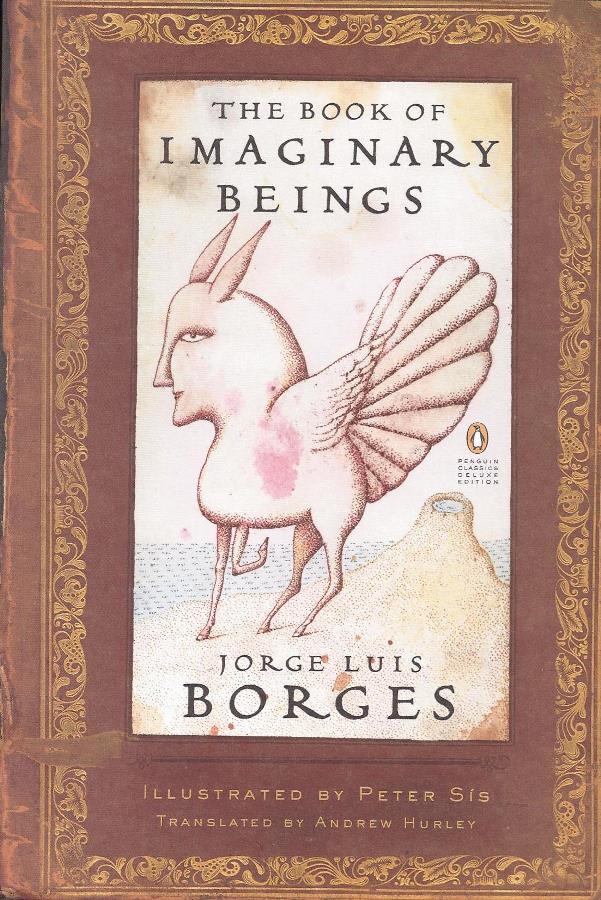

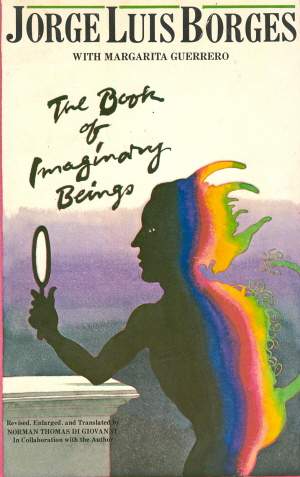

Imaginary Beings

Book

The Sphinx

The Sphinx found on Egyptian monuments (called "Androsphinx" by Herodotus, to distinguish it from the Greek creature) is a recumbent lion with the head of a man; it is believed to represent the authority of the pharaoh, and it guarded the tombs and temples of that land. Other Sphinxes, on the avenues of Karnak, have the head of a lamb, the animal sacred to Amon. Bearded and crowned Sphinxes are found on monuments in Assyria, and it is a common image on Persian jewelry. Pliny includes Sphinxes in his catalog of Ethiopian animals, but the only description he offers is that it has "brown hair and two mammae on the breast." The Greek Sphinx has the head and breasts of a woman, the wings of a bird, and the body and legs of a lion. Others give it the body of a dog and the tail of a serpent. Legend recounts that it devastated the countryside of Thebes by demanding that travelers on the roads solve riddles that it put to them (it had a human voice); it devoured those who could not answer. This was the famous question it put to Oedipus, son of Jocasta: "What has four feet, two feet, or three feet, and the more feet it has, the weaker it is?" (1) Oedipus answered that it was man, who crawls on four legs as a child, walks upon two legs as a man, and leans upon a stick in old age. The Sphinx, its riddle solved, leapt to its death from a mountaintop. In 1849 Thomas De Quincey suggested a second interpretation, which might complement the traditional one. The answer to the riddle, according to De Quincey, is less man in general than Oedipus himself, a helpless orphan in his morning, alone in the fullness of his manhood, and leaning upon Antigone in his blind and hopeless old age. (1) This is apparently the oldest version of the riddle. The years have added the metaphor of the life of man as a single day, so that we now know the following version of it: "What animal walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at midday, and three in the evening? Oedipus and the Enigma

Four-footed at dawn,

in the daytime tall, and wandering three-legged down the hollow reaches of evening: thus did the sphinx, the eternal one, regard his restless fellow, mankind; and at evening came a man who, terror-struck, discovered as in a mirror his own decline set forth in the monstrous image, his destiny, and felt a chill of terror. We are Oedipus and everlastingly we are the long tripartite beast; we are all that we were and will be, nothing less. It would destroy us to look steadily at our full being. Mercifully God grants us the ticking of the clock, forgetfulness. -A.S.T. J.L. Borges [Penguin ed] OEDIPUS AND THE RIDDLE

At dawn four-footed,

at midday erect, And wandering on three legs in the deserted Spaces of afternoon, thus the eternal Sphinx had envisioned her changing brother Man, and with afternoon there came a person Deciphering, appalled at the monstrous other Presence in the mirror, the reflection Of his decay and of his destiny. We are Oedipus; in some eternal way We are the long and threefold beast as well- All that we will be, all that we have been. It would annihilate us all to see The huge shape of our being; mercifully God offers us issue and oblivion. [John Hollander] Thomas Di Giovanni ed Nhân Sư và Thai Đố

Rạng đông bốn chân,

giữa trưa thẳng đứngBa chân, lang thang, nơi không gian hổng vào lúc xế trưa Đó là viễn ảnh của Nhân Sư về người anh em con người của Nàng Vào lúc hoàng hôn, chàng khám phá ra, như trước tấm gương Sự tàn tạ và số mệnh của mình Chúng ta là Ơ Đíp, theo 1 cách miên viễn hằng hằng Chúng ta là con thú, dài dài, ba nếp gấp, chứ còn ai nữa ở đây? Tất cả là như thế, và sẽ là như thế, ngoài ra là hư vô Nó sẽ huỷ diệt chúng ta khi nhìn suốt 1 cõi của mình May mắn thay Chúa bèn ban chúng ta Tiếng tích tắc của cái đồng hồ Và Quên lãng The Lamed Wufniks

On the earth there

are, and have always been, thirty-six just men whose mission is to justify

the world to God. These are the Lamed Wufniks. These men do not know each

other, and they are very poor. If a man comes to realize that he is a Lamed

Wufnik, he immediately dies and another man, perhaps in some other corner

of the earth, takes his place. These men are, without suspecting it, the

secret pillars of the universe. If not for them, God would annihilate the

human race. They are our saviors, though they do not know it. This mystical

belief of the Jewish people has been explained by Max Brod. Its distant roots

may be found in Genesis 18, where God says that He will not destroy the city of Sodom if ten just men can be found within it. The Arabs have an analogous figure, the Qutb, or "saint." Note: Ấn bản mới có tí khác ấn bản cũ, GCC được coi là "Thánh"! The Lamed Wufniks There

are on earth, and always were, thirty-six righteous men whose mission

is to justify the world before God. They are the Lamed Wufniks. They do

not know each other and are very poor. If a man comes to the knowledge that

he is a Lamed Wufnik, he immediately dies and somebody else, perhaps in another

part of the world, takes his place. Lamed Wufniks are, without knowing it,

the secret pillars of the universe. Were it not for them, God would annihilate

the whole of mankind. Unawares, they are our saviors. This mystical belief

of the Jews can be found in the works of Max Brod. Its remote origin may

be the eighteenth chapter of Genesis, where we read this verse: "And the

Lord said, If I find in Sodom fifty righteous within the city, then I will

spare all the place for their sakes."

The Moslems have an analogous personage in the Kutb.

Người Què Gánh Tội

Trên thế giới, có, và luôn luôn có, 36 người què,

còn được gọi là 36 vì công chính, mà sứ mệnh của họ, là, biện minh thế

giới, trước Thượng Đế.

Họ là những tên què gánh tội, Lamed Wufniks. Họ không biết nhau, và rất ư là nghèo khổ. Nếu có 1 tên biết rằng mình là tên què gánh tội, là bèn lập tức, ngỏm củ tỏi. Và một người khác, có lẽ ở đâu đó trên thế giới, thế chỗ anh ta. Không có 36 tên cà chớn này, là liền lập tức, Thượng Đế xóa sổ thế giới.

Cuốn này, mới mua, có minh

họa, cuốn cũ, Cô Út làm từ thiện!

The Sphinx

The Sphinx found on Egyptian monuments (called "Androsphinx" by Herodotus, to distinguish it from the Greek creature) is a recumbent lion with the head of a man; it is believed to represent the authority of the pharaoh, and it guarded the tombs and temples of that land. Other Sphinxes, on the avenues of Karnak, have the head of a lamb, the animal sacred to Amon. Bearded and crowned Sphinxes are found on monuments in Assyria, and it is a common image on Persian jewelry. Pliny includes Sphinxes in his catalog of Ethiopian animals, but the only description he offers is that it has "brown hair and two mammae on the breast." The Greek Sphinx has the head and breasts of a woman, the wings of a bird, and the body and legs of a lion. Others give it the body of a dog and the tail of a serpent. Legend recounts that it devastated the countryside of Thebes by demanding that travelers on the roads solve riddles that it put to them (it had a human voice); it devoured those who could not answer. This was the famous question it put to Oedipus, son of Jocasta: "What has four feet, two feet, or three feet, and the more feet it has, the weaker it is?" (1) Oedipus answered that it was man, who crawls on four legs as a child, walks upon two legs as a man, and leans upon a stick in old age. The Sphinx, its riddle solved, leapt to its death from a mountaintop. In 1849 Thomas De Quincey suggested a second interpretation, which might complement the traditional one. The answer to the riddle, according to De Quincey, is less man in general than Oedipus himself, a helpless orphan in his morning, alone in the fullness of his manhood, and leaning upon Antigone in his blind and hopeless old age. (1) This is apparently the oldest version of the riddle. The years have added the metaphor of the life of man as a single day, so that we now know the following version of it: "What animal walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at midday, and three in the evening?" An Animal Imagined by Kafka It is the animal with the big

tail, a tail many yards long and like a fox's brush. How I should like

to get my hands on this tail some time, but it is impossible, the animal

is constantly moving about, the tail is constantly being flung this way

and that. The animal resembles a kangaroo, but not as to the face, which

is flat almost like a human face, and small and oval; only its teeth have

any power of expression, whether they are concealed or bared. Sometimes I

have the feeling that the animal is trying to tame me. What other purpose

could it have in withdrawing its tail when I snatch at it, and then again

waiting calmly until I am tempted again, and then leaping away once more?

FRANZ KAFKA: Dearest Father (Translated from the

German by Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins) Một con vật

Kafka tưởng tượng ra

Ðó là 1 con vật có 1 cái đuôi lớn, dài nhiều mét, giống đuôi chồn. Ðòi phen tôi thèm được sờ 1 phát vào cái đuôi của em, [hãy nhớ cái cảnh, 1 anh học sinh, xa nhà, trọ học, đêm đêm được chồn viếng thăm, trong Liêu Trai, nhá!] nhưng vô phương, con vật cứ ngoe nguẩy cái đuôi, thân hình luôn uốn oéo. Con vật giống như con kangaro, nhưng cái mặt không giống, bèn bẹt y chang mặt người, nho nhỏ, xinh xinh, như cái gương bầu dục, chỉ có hàm răng là biểu hiện rõ rệt nhất của tình cảm của em chồn này, lúc thì giấu biệt, lúc thì phô ra. Ðôi khi tôi có cảm tưởng em tính thuần hóa tôi, biến tôi thành 1 con vật nuôi trong nhà, quanh quẩn bên em. Hẳn là thế, nếu không tại sao em thu cái đuôi lại, khi tôi với tay tính sờ 1 phát, và sau đó lại nhu mì ngồi, cho tới khi tôi thèm quá, thò tay ra, và em lại nguẩy 1 phát, đau nhói tim? The Lamed Wufniks The Moslems have an analogous personage in the Kutb.

Người Què Gánh Tội

Trên thế giới, có, và luôn luôn có, 36 người què, còn được gọi là 36 vì công chính, mà sứ mệnh của họ, là, biện minh thế giới, trước Thượng Đế. Họ là những tên què gánh tội, Lamed Wufniks. Họ không biết nhau, và rất ư là nghèo khổ. Nếu có 1 tên biết rằng mình là tên què gánh tội, là bèn lập tức, ngỏm củ tỏi. Và một người khác, có lẽ ở đâu đó trên thế giới, thế chỗ anh ta. Không có 36 tên cà chớn này, là liền lập tức, Thượng Đế xóa sổ thế giới.

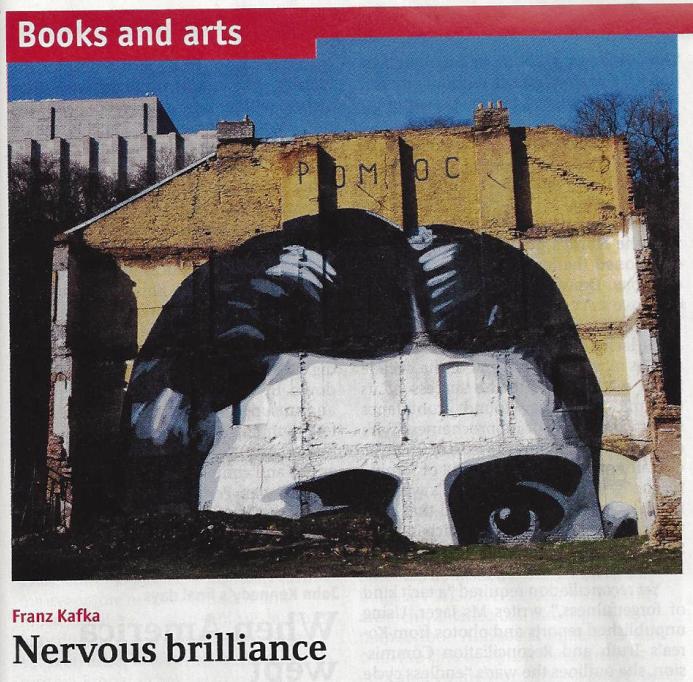

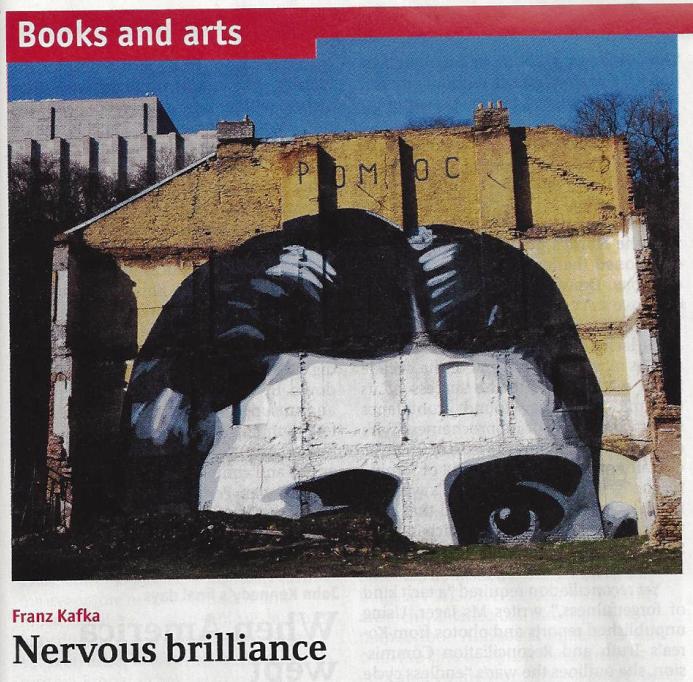

Note: Nervous brilliance, tạm dịch, “sáng

chói bồn chồn”. Nhưng cuốn tiểu sử của Mr Stach

cũng cho thấy cái phần nhẹ nhàng, sáng sủa hơn của Kafka. Trong 1 lần

holyday, đi chơi với bồ, ông cảm thấy mình bịnh, vì cười nhiều quá. Trong

những năm sau cùng của đời mình, ông gặp 1 cô gái ngồi khóc ở 1 công viên,

và cô nàng nói với ông, là cô làm mất con búp bế. Thế là mỗi ngày ông

viết cho cô bé 1 lá thư, trong ba tuần lễ, lèm bèm về con búp bế bị mất.

Với người tình sau cùng, Dora Diamant, rõ là ông tính lấy làm vợ. Cô này

còn dụ ông trở lại được với Do Thái giáo. Kết cục thì nó phải như thế đó: Đếch làm sao

giải thích được! Trên TLS, số 7 Sept 2012,

GABRIEL JOSIPOVIC điểm 1 số sách mới ra lò về Kafka - vị thầy gối đầu giường

của Sến - đưa ra nhận xét, vào cái ngày 23 Tháng Chín này, thì kể như là

đúng 100 năm, ngày Kafka viết cái truyện ngắn khủng ơi là khủng, “Sự

Xét Xử”. Và có thể nói, vào giờ này, độc giả chúng ta cũng chẳng hiểu ông

nhiều hơn, so với những độc giả đầu tiên của ông, và có lẽ sự thể nó phải

như thế, nghĩa là nó phải chấm dứt bằng cái sự đếch làm sao hiểu được Kafka! Ở đây, cũng phải đi 1 đường

ghi chú ngoài lề! 1. Cuốn Bếp Lửa

của TTT, chấm dứt bằng lá thư của 1 tên Mít, là Tâm, bỏ đất mẹ ra

đi, đếch thèm trở về, viết cho cô em bà con, buộc vào quê hương thì phải

là ruột thịt, máu mủ. (1) 2. Cuốn Sinh Nhật

của bạn quí của Gấu, NXH, khi mới ra lò, Gấu đề nghị, nên đổi tít,

là Sinh Nhạt, và còn đề nghị viết bài phê bình điểm sách,

“Đi tìm 1 cái mũ đã mất”: Truyện ngắn mà Brod gọi là

"Prometheus", được kiếm thấy trong Sổ Tay Octavo Notebooks, của Kafka,

đã được gạch bỏ [crossed out]. Câu kết thúc của truyện: “Giai thoại thường

toan tính giải thích cái không thể giải thích; bởi vì dưng không trồi lên

sự thực [chữ của TTT, trong Cát Lầy],

nó phải lại chấm dứt trong không thể cắt nghĩa được” Nói rõ hơn, nhân loại không

làm sao đọc được Kafka, vì có 1 thằng cà chớn Gấu "nào đó", nẫng mẹ mất

cái nón đội đầu của ông!

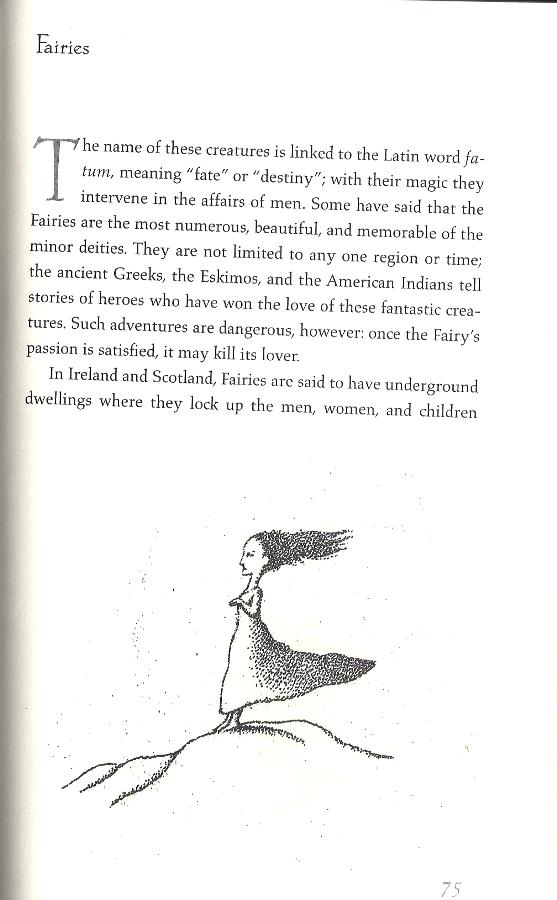

Fairies The name of these creatures is linked to the Latin word faturn, meaning "fate" or "destiny"; with their magic they intervene in the affairs of men. Some have said that the Fairies are the most numerous, beautiful, and memorable of the minor deities. They are not limited to anyone region r time; the ancient Greeks, the Eskimos, and the American Indians tell stories of heroes who have won the love of these fantastic creatures. Such adventures are dangerous, however: once the Fairy's passion is satisfied, it may kill its lover. In Ireland and Scotland, Fairies are said to have underground dwellings where they lock up the men, women, and children that they kidnap. People believe that the neolithic arrowheads they dig up in their fields once belonged to the Fairies, and that these arrowheads possess unfailing medicinal properties. Fairies like singing and music and the color green. In the late seventeenth century, a Scottish cleric, one Reverend Kirk, of Aberfoyle, compiled a treatise titled The Secret Commonwealth of the Elves, Fairies, and Fauns. In 1815, Sir Walter Scott had Kirk's manuscript printed. Mr. Kirk was said to have been carried off by the Fairies because he had revealed their secrets. In the seas off Italy, there is a Fairy, the Fata Morgana, that weaves mirages that con- fuse sailors and make them lose their course. 67

Cuốn sách những sinh vật tưởng tượng An Animal Imagined by Kafka It is the animal with the big

tail, a tail many yards long and like a fox's brush. How I should like to

get my hands on this tail some time, but it is impossible, the animal is

constantly moving about, the tail is constantly being flung this way and

that. The animal resembles a kangaroo, but not as to the face, which is flat

almost like a human face, and small and oval; only its teeth have any power

of expression, whether they are concealed or bared. Sometimes I have the

feeling that the animal is trying to tame me. What other purpose could it

have in withdrawing its tail when I snatch at it, and then again waiting

calmly until I am tempted again, and then leaping away once more? FRANZ KAFKA: Dearest Father (Translated from the

German by Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins) Một con vật

Kafka tưởng tượng ra

Ðó là 1 con vật có 1 cái đuôi lớn, dài nhiều mét, giống đuôi chồn. Ðòi phen tôi thèm được sờ 1 phát vào cái đuôi của em, [hãy nhớ cái cảnh, 1 anh học sinh, xa nhà, trọ học, đêm đêm được chồn viếng thăm, trong Liêu Trai, nhá!] nhưng vô phương, con vật cứ ngoe nguẩy cái đuôi, thân hình luôn uốn oéo. Con vật giống như con kangaro, nhưng cái mặt không giống, bèn bẹt y chang mặt người, nho nhỏ, xinh xinh, như cái gương bầu dục, chỉ có hàm răng là biểu hiện rõ rệt nhất của tình cảm của em chồn này, lúc thì giấu biệt, lúc thì phô ra. Ðôi khi tôi có cảm tưởng em tính thuần hóa tôi, biến tôi thành 1 con vật nuôi trong nhà, quanh quẩn bên em. Hẳn là thế, nếu không tại sao em thu cái đuôi lại, khi tôi với tay tính sờ 1 phát, và sau đó lại nhu mì ngồi, cho tới khi tôi thèm quá, thò tay ra, và em lại nguẩy 1 phát, đau nhói tim? The Bloi and the Morlocks

The hero of the novel The Time Machine, which a young writer

Herbert George Wells published in 1895, travels on a mechanical device into

an unfathomable future. There he finds that mankind has split into two species:

the Eloi, who are frail and defenseless aristocrats living in idle gardens

and feeding on the fruits of the trees; and the Morlocks, a race of underground

proletarians who, after ages of laboring in darkness, have gone blind, but

driven by the force of the past, go on working at their rusted intricate

machinery that produces nothing. Shafts with winding staircases unite the

two worlds. On moonless nights, the Morlocks climb up out of their caverns

and feed on the Eloi. The nameless hero, pursued by Morlocks, escapes back into the present. He brings with him as a solitary token of his adventure an unknown flower that falls into dust and that will not blossom on earth until thousands and thousands of years are over. Nguỵ vs VC

Nhân vật chính trong cuốn tiểu thuyết “Máy Thời Gian”, sử dụng cái

máy thần sầu du lịch xuyên qua thời gian tới những miền tương lai không làm

sao mà dò được. Ở đó, anh ta thấy Mít – nhân loại - được chia thành hai, một,

gọi là Ngụy, yếu ớt, ẻo lả, và là những nhà trưởng giả, bất lực, vô phương

chống cự, sống trong những khu vườn nhàn nhã, ăn trái cây, và một, VC, gồm

những tên bần cố nông, vô sản, sống dưới hầm, địa đạo [Củ Chi, thí dụ], và,

do bao nhiêu đời lao động trong bóng tối, trở thành mù, và, được dẫn dắt

bởi sức mạnh kẻ thù nào cũng đánh thắng, với sức người sỏi đá cũng thành

cơm, cứ thế cứ thế lao động, để thâu hoạch chẳng cái gì. Có những cầu thang

nối liền hai thế giới, và vào những đêm không trăng, VC, từ những hang động,

hầm hố, bò lên làm thịt lũ Ngụy. Nhân vật chính, không tên, bị VC truy đuổi, trốn thoát được, và trở lại thời hiện tại. Anh ta mang theo cùng với anh, một BHD, như chứng tích của cuộc phiêu lưu, và vừa trở lại hiện tại, bông hồng bèn biến thành tro bụi, và, như…. Cô Sáu trong Tiền Kiếp Của GCC, hàng hàng đời sau, sẽ có ngày nào đó, bông hồng lại sống lại… Who knows? Hà, hà! The Tigers of Annam

To the Annamites, tigers, or spirits who dwell in tigers, govern the four corners of space. The Red Tiger rules over the South (which is located at the top of maps); summer and fire belong to him. The Black Tiger rules over the North; winter and water belong to him. The Blue Tiger rules over the East; spring and plants belong to him. The White Tiger rules over the West; autumn and metals belong to him. Over these Cardinal Tigers is a fifth tiger, the Yellow Tiger, who stands in the middle governing the others, just as the Emperor stands in the middle of China and China in the middle of the World. (That's why it is called the Middle Kingdom; that's why it occupies the middle of the map that Father Ricci, of the Society of Jesus, drew at the end of the sixteenth century for the instruction of the Chinese.) Lao-tzu entrusted to the Five Tigers the mission of waging war against devils. An Annamite prayer, translated into French by Louis Cho Chod, implores the aid of the Five Heavenly Tigers. This superstition is of Chinese origin; Sinologists speak of a White Tiger that rules over the remote region of the western stars. To the South the Chinese place a Red Bird; to the East, a Blue Dragon; to the North, a Black Tortoise. As we see, the Annamites have preserved the colors but have made the animals one. Hổ An Nam Trên những hổ này, là hổ thứ năm, Hổ Vàng, ở giữa, cai quản chúng, y chang Hoàng Đế Tẫu, ở Trung Nguyên, tức trung tâm nước Tẫu, và nước Tẫu, đến lượt nó, là trung tâm Thế Giới, chính vì thế mới có tên Vương Quốc Tẫu, hay,Vương Quốc Trung Nguyên. Chính vì thế mà Cha Ricci, của Hội Giê Su, vào cuối thế kỷ 16 đã đi 1 đường bản đồ chỉ dẫn về người nướcTẫu. Lão Tử trao cho Ngũ Hổ thiên chức làm cuộc chiến chống lại quỉ ma. Một cầu nguyện bằng tiếng An Nam Mít, được Louis Cho Chod dịch sang tiếng Tẩy, khẩn cầu sự trợ giúp của Ngũ Hổ Nhà Trời. Sự mê tín có nguồn gốc Tẫu; những nhà Tẫu học nói tới một vì Bạch Hổ trị miền xa xôi của những ngôi sao Tây Phương. Ở Miền Nam, người Tẫu đặt một Chim Đỏ; miền Đông, Rồng Xanh, miền Bắc, Rùa Đen. Như chúng ta thấy, người Mít giữ những mầu sắc, nhưng coi những con vật, là một. The Bloi and the Morlocks

The hero of the novel The Time Machine, which a young writer Herbert

George Wells published in 1895, travels on a mechanical device into an unfathomable

future. There he finds that mankind has split into two species: the Eloi,

who are frail and defenseless aristocrats living in idle gardens and feeding

on the fruits of the trees; and the Morlocks, a race of underground proletarians

who, after ages of laboring in darkness, have gone blind, but driven by the

force of the past, go on working at their rusted intricate machinery that

produces nothing. Shafts with winding staircases unite the two worlds. On

moonless nights, the Morlocks climb up out of their caverns and feed on

the Eloi. The nameless hero, pursued by Morlocks, escapes back into the present. He brings with him as a solitary token of his adventure an unknown flower that falls into dust and that will not blossom on earth until thousands and thousands of years are over. Nguỵ vs VC

Nhân vật chính trong cuốn tiểu thuyết “Máy Thời Gian”, sử dụng cái máy

thần sầu du lịch xuyên qua thời gian tới những miền tương lai không làm

sao mà dò được. Ở đó, anh ta thấy Mít – nhân loại - được chia thành hai,

một, gọi là Ngụy, yếu ớt, ẻo lả, và là những nhà trưởng giả, bất lực, vô

phương chống cự, sống trong những khu vườn nhàn nhã, ăn trái cây, và một,

VC, gồm những tên bần cố nông, vô sản, sống dưới hầm, địa đạo [Củ Chi, thí

dụ], và, do bao nhiêu đời lao động trong bóng tối, trở thành mù, và, được

dẫn dắt bởi sức mạnh kẻ thù nào cũng đánh thắng, với sức người sỏi đá cũng

thành cơm, cứ thế cứ thế lao động, để thâu hoạch chẳng cái gì. Có những cầu

thang nối liền hai thế giới, và vào những đêm không trăng, VC, từ những hang

động, hầm hố, bò lên làm thịt lũ Ngụy. Nhân vật chính, không tên, bị VC truy đuổi, trốn thoát được, và trở lại thời hiện tại. Anh ta mang theo cùng với anh, một BHD, như chứng tích của cuộc phiêu lưu, và vừa trở lại hiện tại, bông hồng bèn biến thành tro bụi, và, như…. Cô Sáu trong Tiền Kiếp Của GCC, hàng hàng đời sau, sẽ có ngày nào đó, bông hồng lại sống lại… Who knows? Hà, hà! The Tigers of Annam

To the Annamites, tigers, or spirits who dwell in tigers, govern the four corners of space. The Red Tiger rules over the South (which is located at the top of maps); summer and fire belong to him. The Black Tiger rules over the North; winter and water belong to him. The Blue Tiger rules over the East; spring and plants belong to him. The White Tiger rules over the West; autumn and metals belong to him. Over these Cardinal Tigers is a fifth tiger, the Yellow Tiger, who stands in the middle governing the others, just as the Emperor stands in the middle of China and China in the middle of the World. (That's why it is called the Middle Kingdom; that's why it occupies the middle of the map that Father Ricci, of the Society of Jesus, drew at the end of the sixteenth century for the instruction of the Chinese.) Lao-tzu entrusted to the Five Tigers the mission of waging war against devils. An Annamite prayer, translated into French by Louis Cho Chod, implores the aid of the Five Heavenly Tigers. This superstition is of Chinese origin; Sinologists speak of a White Tiger that rules over the remote region of the western stars. To the South the Chinese place a Red Bird; to the East, a Blue Dragon; to the North, a Black Tortoise. As we see, the Annamites have preserved the colors but have made the animals one. The Sphinx

The Sphinx of Egyptian monuments (called by Herodotus androsphinx, or

man-sphinx, in order to distinguish it from the Greek Sphinx) is a lion having

the head of a man and lying at rest; it stood watch by temples and tombs:

and is said to have represented royal authority. In the halls of Karnak,

other Sphinxes have the head of a ram, the sacred animal of Amon. The Sphinx

of Assyrian monuments is a winged bull with a man's bearded and crowned

head; this image is common on Persian gems. Pliny in his list of Ethiopian

animals includes the Sphinx, of which he details no other features than

"brown hair and two mammae on the breast." The Greek Sphinx has a woman's head and breasts, the wings of a bird, and the body and feet of a lion. Some give it the body of a dog and a snake's tail. It is told that it depopulated the Theban countryside asking riddles (for it had a human voice) and making a meal of any man who could not give the answer. Of Oedipus, the son of Jocasta, the Sphinx asked, "What has four legs, two legs, and three legs, and the more legs it has the weaker it is?" (So runs what seems to be the oldest version. In time the metaphor was introduced which makes of man's life a single day. Nowadays the question goes, "Which anima] walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three in the evening?") Oedipus answered that it was a man 'who as an infant crawls on all fours, when he grows up walks on two legs, and in old age leans on a staff. The riddle solved, the Sphinx threw herself from a precipice. De Quincey, around 1849, suggested a second interpretation, which complements the traditional one. The subject of the riddle according to him is not so much man in general as it is Oedipus in particular, orphaned and helpless at birth, alone in his manhood, and supported by Antigone in his blind and hopeless old age. The, Elephant

That Foretold the Birth of the Buddha Five centuries before the Christian era, Queen Maya, in Nepal, had a dream that a white Elephant, which dwelled on the Golden Mountain, had entered her body. This visionary beast was furnished with six tusks. The King's soothsayers predicted that the Queen would bear a son who would become either ruler of the world or the savior of mankind. As is common knowledge, the latter came true. In India the Elephant is a domestic animal. White stands for humility and the number six is sacred, corresponding to the six dimensions of space: upward, downward, forward, back, left, and right. An Animal Imagined by Kafka It is the animal with the big

tail, a tail many yards long and like a fox's brush. How I should like to

get my hands on this tail some time, but it is impossible, the animal is

constantly moving about, the tail is constantly being flung this way and

that. The animal resembles a kangaroo, but not as to the face, which is flat

almost like a human face, and small and oval; only its teeth have any power

of expression, whether they are concealed or bared. Sometimes I have the

feeling that the animal is trying to tame me. What other purpose could it

have in withdrawing its tail when I snatch at it, and then again waiting

calmly until I am tempted again, and then leaping away once more? FRANZ KAFKA: Dearest Father (Translated from the

German by Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins) Một con vật

Kafka tưởng tượng ra

Ðó là 1 con vật có 1 cái đuôi lớn, dài nhiều mét, giống đuôi chồn. Ðòi phen tôi thèm được sờ 1 phát vào cái đuôi của em, [hãy nhớ cái cảnh, 1 anh học sinh, xa nhà, trọ học, đêm đêm được chồn viếng thăm, trong Liêu Trai, nhá!] nhưng vô phương, con vật cứ ngoe nguẩy cái đuôi, thân hình luôn uốn oéo. Con vật giống như con kangaro, nhưng cái mặt không giống, bèn bẹt y chang mặt người, nho nhỏ, xinh xinh, như cái gương bầu dục, chỉ có hàm răng là biểu hiện rõ rệt nhất của tình cảm của em chồn này, lúc thì giấu biệt, lúc thì phô ra. Ðôi khi tôi có cảm tưởng em tính thuần hóa tôi, biến tôi thành 1 con vật nuôi trong nhà, quanh quẩn bên em. Hẳn là thế, nếu không tại sao em thu cái đuôi lại, khi tôi với tay tính sờ 1 phát, và sau đó lại nhu mì ngồi, cho tới khi tôi thèm quá, thò tay ra, và em lại nguẩy 1 phát, đau nhói tim? A Crossbreed

I have a curious animal, half-cat, half-lamb. It is a legacy from my father. But it only developed in my time; formerly it was far more lamb than cat. Now it is both in about equal parts. From the cat it takes its head and claws, from the lamb its size and shape; from both its eyes, which are wild and changing, its hair, which is soft, lying close to its body, its movements, which partake both of skipping and slinking. Lying on the window-sill in the sun it curls itself up in a ball and purrs; out in the meadow it rushes about as if mad and is scarcely to be caught. It flies from cats and makes to attack lambs. On moonlight nights its favorite promenade is the tiles. It cannot mew and it loathes rats. Beside the hen-coop it can lie for hours in ambush, but it has never yet seized an opportunity for murder. I feed it on milk; that seems to suit it best. In long draughts it sucks the milk into it through its teeth of a beast of prey. Naturally it is a great source of entertainment for children. Sunday morning is the visiting hour. I sit with the little beast on my knees, and the children of the whole neighborhood stand round me. Then the strangest questions are asked, which no human being could answer: Why there is only one such animal, why I rather than anybody else should own it, whether there was ever an animal like it before and what would happen if it died, whether it feels lonely, why it has no children, what it is called, etc. I never trouble to answer, but confine myself without further explanation to exhibiting my possession. Sometimes the children bring cats with them; once they actually brought two lambs. But against all their hopes there was no scene of recognition. The animals gazed calmly at each other with their animal eyes, and obviously accepted their reciprocal existence as a divine fact. Sitting on my knees the beast knows neither fear nor lust of pursuit. Pressed against me it is happiest. It remains faithful to the family that brought it up. In that there is certainly no extraordinary mark of fidelity, but merely the true instinct of an animal which, though it has countless step-relations in the world, has perhaps not a single blood relation, and to which consequently the protection it has found with us is sacred. Sometimes I cannot help laughing when it sniffs round me and winds itself between my legs and simply will not be parted from me. Not content with being lamb and cat, it almost insists on being a dog as well. Once when, as may happen to anyone, I could see no way out of my business difficulties and all that depends on such things, and had resolved to let everything go, and in this mood was lying in my rocking-chair in my room, the beast on my knees, I happened to glance down and saw tears dropping from its huge whiskers. Were they mine, or were they the animal's? Had this cat, along with the soul of a lamb, the ambitions of a human being? I did not inherit much from my father, but this legacy is worth looking at. It has the restlessness of both beasts, that of the cat and that of the lamb, diverse as they are. For that reason its skin feels too narrow for it. Sometimes it jumps up on the armchair beside me, plants its front legs on my shoulder, and puts its muzzle to my ear. It is as if it were saying something to me, and as a matter of fact it turns its head afterwards and gazes in my face to see the impression its communication has made. And to oblige it I behave as if I had understood and nod. Then it jumps to the floor and dances about with joy. Perhaps the knife of the butcher would be a release for this animal; but as it is a legacy I must deny it that. So it must wait until the breath voluntarily leaves its body, even though it sometimes gazes at me with a look of human understanding, challenging me to do the thing of which both of us are thinking. FRANZ KAFKA: Description of a Struggle (Translated from the German by Tania and James Stern) Jorge Luis Borges: The Book of Imaginary Beings I have a curious animal, half-cat, half-lamb. It is a legacy from my father: Tôi có 1 con vật kỳ kỳ, nửa mèo, nửa cừu. Nó là gia tài để lại của ông già của tôi Không phải ngẫu nhiên mà Gregor Samsa thức giấc như là một con bọ ở trong nhà bố mẹ, mà không ở một nơi nào khác, và cái con vật khác thường nửa mèo nửa cừu đó, là thừa hưởng từ người cha. Walter Benjamin Perhaps the knife of the butcher would be a release for this animal; but as it is a legacy I must deny it that. So it must wait until the breath voluntarily leaves its body, even though it sometimes gazes at me with a look of human understanding, challenging me to do the thing of which both of us are thinking. Có lẽ con dao của tên đồ tể là 1 giải thoát cho con vật, nhưng tớ đếch chịu như thế, đối với gia tài của bố tớ để lại cho tớ. Vậy là phải đợi cho đến khi hơi thở cuối cùng hắt ra từ con vật khốn khổ khốn nạn, mặc dù đôi lúc, con vật nhìn tớ với cái nhìn thông cảm của 1 con người, ra ý thách tớ, mi làm cái việc đó đi, cái việc mà cả hai đều đang nghĩ tới đó! Con chim giận dữ Một con kên kên đợp chân tôi.

Nó xé giầy vớ thành từng miểng; bây giờ tới cẳng. Nó đợp, xỉa tới tấp, lâu

lâu lại lượn vòng, và đợp tiếp. Một vị lữ hành phong nhã đi qua, nhìn ngắm

một lúc, rồi hỏi tôi, tại làm sao mà đau khổ như thế vì con kên kên. “Tôi

làm sao bây giờ?” “Khi con vật bay tới tấn công, lẽ dĩ nhiên tôi cố đuổi

nó đi, tôi còn tính bóp cổ nó nữa, nhưng loài thú này khoẻ lắm, nó chồm

tới, tính đợp vô mặt tôi, và tôi đành hy sinh cặp giò. Bây giờ nó xé nát

ra từng mảnh rồi.” Kafka: Years of insight

Note: Nervous brilliance, tạm

dịch, “sáng chói bồn chồn”. Nhưng cuốn tiểu sử của Mr Stach

cũng cho thấy cái phần nhẹ nhàng, sáng sủa hơn của Kafka. Trong 1 lần holyday,

đi chơi với bồ, ông cảm thấy mình bịnh, vì cười nhiều quá. Trong những năm

sau cùng của đời mình, ông gặp 1 cô gái ngồi khóc ở 1 công viên, và cô nàng

nói với ông, là cô làm mất con búp bế. Thế là mỗi ngày ông viết cho cô bé

1 lá thư, trong ba tuần lễ, lèm bèm về con búp bế bị mất. Với người tình

sau cùng, Dora Diamant, rõ là ông tính lấy làm vợ. Cô này còn dụ ông trở

lại được với Do Thái giáo. Kết cục thì nó phải như thế đó: Đếch làm sao

giải thích được! Trên TLS, số 7 Sept 2012, GABRIEL

JOSIPOVIC điểm 1 số sách mới ra lò về Kafka - vị thầy gối đầu giường của

Sến - đưa ra nhận xét, vào cái ngày 23 Tháng Chín này, thì kể như là đúng

100 năm, ngày Kafka viết cái truyện ngắn khủng ơi là khủng, “Sự Xét Xử”.

Và có thể nói, vào giờ này, độc giả chúng ta cũng chẳng hiểu ông nhiều hơn,

so với những độc giả đầu tiên của ông, và có lẽ sự thể nó phải như thế, nghĩa

là nó phải chấm dứt bằng cái sự đếch làm sao hiểu được Kafka! Ở đây, cũng phải đi 1 đường

ghi chú ngoài lề! 1. Cuốn Bếp Lửa

của TTT, chấm dứt bằng lá thư của 1 tên Mít, là Tâm, bỏ đất mẹ ra đi, đếch

thèm trở về, viết cho cô em bà con, buộc vào quê hương thì phải là ruột

thịt, máu mủ. (1) 2. Cuốn Sinh Nhật

của bạn quí của Gấu, khi mới ra lò, Gấu đề nghị, nên đổi tít, là Sinh Nhạt, và còn đề nghị viết bài phê bình điểm sách, “Đi

tìm 1 cái mũ đã mất”: Truyện ngắn mà Brod gọi là "Prometheus",

được kiếm thấy trong Sổ Tay Octavo Notebooks, của Kafka, đã được gạch bỏ

[crossed out]. Câu kết thúc của truyện: “Giai thoại thường toan tính giải

thích cái không thể giải thích; bởi vì dưng không trồi lên sự thực [chữ của

TTT, trong Cát Lầy], nó phải lại

chấm dứt trong không thể cắt nghĩa được” Nói rõ hơn, nhân loại không

làm sao đọc được Kafka, vì có 1 thằng cà chớn Gấu "nào đó", nẫng mẹ mất cái

nón đội đầu của ông! Youwarkee

In his Short History of English Literature,

Saintsbury finds the flying girl Youwarkee one of the most charming heroines

of the eighteenth-century novel. Half woman and half bird, or-as Browning

was to write of his dead wife, Elizabeth Barrett-half angel and half bird,

she can open her arms and make wings of them, and a silky down covers her

body. She lives on an island lost in Antarctic seas and was discovered there

by Peter Wilkins, a shipwrecked sailor, who marries her. Youwarkee is a gawry

(or flying woman) and belongs to a race of flying people known as glumms.

Wilkins converts them to Christianity and, after the death of his wife, succeeds

in making his way back to England. The story of this strange love affair may

be read in the novel Peter Wilkins (1751) by Robert Paltock.Trong Lịch sử bỏ túi văn học Anh,

Saintsbury nhận ra người đẹp bay, Youwarkee, là nhân vật nữ tuyệt vời nhất

của tiểu thuyết thế kỷ 18. Nửa đờn bà, nửa chim, hay là - như Browning viết

về bà vợ đã mất của mình, là Elizabeth Barrett- nửa thiên thần, nửa chim,

nàng có thể mở rộng đôi tay, làm thành đôi cánh, và mượn mà phủ nó lên cái

body thần tiên của nàng. The Double Suggested or stimulated by reflections

in mirrors and in water and by twins, the idea of the Double is common to

many countries. It is likely that sentences such as A friend is another

self by Pythagoras or the Platonic Know thyself were inspired by it. In

Germany this Double is called Doppelganger, which means "double walker."

In Scotland there is the fetch, which comes to fetch a man to bring him

to his death; there is also the Scottish word wraith for an apparition thought

to be seen by a person in his exact image just before death. To meet oneself

is, therefore, ominous. The tragic ballad "Ticonderoga" by Robert Louis

Stevenson tells of a legend on this theme. There is also the strange picture

by Rossetti ("How They Met Themselves") in which two lovers come upon themselves

in the dusky gloom of a woods. We may also cite examples from Hawthorne ("Howe's

Masquerade"), Dostoyevsky, Alfred de Musset, James ("The Jolly Corner"),

Kleist, Chesterton ("The Mirror of Madmen"), and Hearn (Some Chinese Ghosts). The ancient Egyptians believed

that the Double, the ka, was a man's exact counterpart, having his same

walk and his same dress. Not only men, but gods and beasts, stones and trees,

chairs and knives had their ka, which was invisible except to certain priests

who could see the Doubles of the gods and were granted by them a knowledge

of things past and things to come. To the Jews the appearance of

one's Double was not an omen of imminent death. On the contrary, it was

proof of having attained prophetic powers. This is how it is explained by

Gershom Scholem. A legend recorded in the Talmud tells the story of a man

who, in search of God, met himself. In the

story "William Wilson" by Poe, the Double is the hero's conscience. He kills

it and dies. In a similar way, Dorian Gray in Wilde's novel stabs his portrait

and meets his death. In Yeats’s poems the Double is our other side, our

opposite, the one who complements us, the one we are not nor will ever become. Plutarch writes that the Greeks gave the name other self to a king's ambassador. Kẻ Kép Ðược đề xuất, dẫn dụ, huých

huých bởi những phản chiếu từ gương soi, từ mặt nước, từ cặp song sinh, ý

tưởng về Kẻ Kép thì thông thuộc trong nhiều xứ sở. Thí dụ câu này “Bạn Quí

là một GNV khác”, của Pythagore, và cái tư tưởng Hãy Biết Mình của trường

phái Platonic được gợi hứng từ đó. Trong tiếng Ðức, Kẻ Kép được gọi là Doppelganger,

có nghĩa, “người đi bộ sóng đôi, kép”. Trong tiếng Scotland thì là từ fetch,

cũng có nghĩa là “bạn quí”, nhưng ông bạn quí này đem cái chết đến cho bạn.

Còn có từ wraith, tiếng Scottish, có nghĩa là hồn ma, y chang bạn, và bạn

chỉ vừa kịp nhìn thấy, là thở hắt ra, đi một đường ô hô ai tai! Thành ra cái chuyện “Gấu gặp

bạn quí là Gấu”, ngồi bờ sông lâu thể nào cũng thấy xác của mình trôi qua,

quả đáng ngại thật. Ðiềm gở. Khúc “ba lát” bi thương "Ticonderoga" của Robert

Louis Stevenson kể 1 giai thoại về đề tài này. Bức họa lạ lùng của Rossetti

[Họ gặp chính họ như thế nào, "How They Met Themselves"], hai kẻ yêu nhau

đụng đầu trong khu rừng âm u vào lúc chạng vạng. Còn nhiều thí dụ nữa, từ

Hawthorne ("Howe's Masquerade"), Dostoyevsky, Alfred de Musset, James ("The

Jolly Corner"), Kleist, Chesterton ("The Mirror of Madmen"), and Hearn (Some

Chinese Ghosts). Những người Ai Cập cổ tin tưởng,

Kẻ Kép, the “ka”, là cái phần đối chiếu đích thị của 1 con người, kẻ đối

tác có cùng bước đi, cùng chiếc áo dài. Không chỉ con người mà thần thánh,

thú vật, đá, cây, ghế, dao, đều có “ka” của chúng, vô hình, trừ một vài ông

thầy tu là có thể nhìn thấy Kẻ Kép của những vị thần và được thần ban cho

khả năng biết được những sự vật đã qua và sắp tới. Với người Do Thái, sự xuất hiện

Kẻ Kép không phải là điềm gở, [tới giờ đi rồi cha nội, lẹ lên không lỡ chuyến

tầu suốt, rồi không làm sao mà đi được, như Cao Bồi, bạn của Gấu, như Võ

Ðại Tướng, vừa mới chợp mắt tính... đi, là đã thấy

3 triệu oan hồn hau háu, đau đáu chờ đòi mạng, thì đi thế đéo nào được?].

Ngược lại, họ tin đó là bằng chứng bạn tu luyện đã thành, đạt được những

quyền năng tiên tri. Ðó là cách giải thích của Gershom Scholem. Một giai thoại được ghi lại

trong Talmud kể câu chuyện một thằng cha GNV, suối đời tìm hoài Thượng Ðế,

và khi gặp, hóa ra là… GCC! Trong “William Wilson” của Poe,

Kẻ Kép là lương tâm của nhân vật trong truyện. Anh ta thịt nó, thế là bèn

ngỏm theo. Cũng cùng đường hướng như vậy, Dorian Gray, trong tiểu thuyết

của Wilde, đâm bức hình của anh ta, và bèn gặp gỡ Thần Chết. Trong những

bài thơ của Yeats, Kẻ Kép là phía bên kia của chúng ta, kẻ bổ túc, hoàn thiện

chúng ta, kẻ mà chúng ta không, và sẽ chẳng bao giờ trở thành. An Animal Imagined by Kafka It is the animal with the big

tail, a tail many yards long and like a fox's brush. How I should like to

get my hands on this tail some time, but it is impossible, the animal is

constantly moving about, the tail is constantly being flung this way and

that. The animal resembles a kangaroo, but not as to the face, which is flat

almost like a human face, and small and oval; only its teeth have any power

of expression, whether they are concealed or bared. Sometimes I have the

feeling that the animal is trying to tame me. What other purpose could it

have in withdrawing its tail when I snatch at it, and then again waiting

calmly until I am tempted again, and then leaping away once more? FRANZ KAFKA: Dearest Father (Translated from the

German by Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins) Một con vật

Kafka tưởng tượng ra

Ðó là 1 con vật có 1 cái đuôi lớn, dài nhiều mét, giống đuôi chồn. Ðòi phen tôi thèm được sờ 1 phát vào cái đuôi của em, [hãy nhớ cái cảnh, 1 anh học sinh, xa nhà, trọ học, đêm đêm được chồn viếng thăm, trong Liêu Trai, nhá!] nhưng vô phương, con vật cứ ngoe nguẩy cái đuôi, thân hình luôn uốn oéo. Con vật giống như con kangaro, nhưng cái mặt không giống, bèn bẹt y chang mặt người, nho nhỏ, xinh xinh, như cái gương bầu dục, chỉ có hàm răng là biểu hiện rõ rệt nhất của tình cảm của em chồn này, lúc thì giấu biệt, lúc thì phô ra. Ðôi khi tôi có cảm tưởng em tính thuần hóa tôi, biến tôi thành 1 con vật nuôi trong nhà, quanh quẩn bên em. Hẳn là thế, nếu không tại sao em thu cái đuôi lại, khi tôi với tay tính sờ 1 phát, và sau đó lại nhu mì ngồi, cho tới khi tôi thèm quá, thò tay ra, và em lại nguẩy 1 phát, đau nhói tim? The Lamed Wufniks The Moslems have an analogous personage in the Kutb.

Người Què Gánh Tội

Trên thế giới, có, và luôn luôn có, 36 người què, còn được gọi là 36 vì công chính, mà sứ mệnh của họ, là, biện minh thế giới, trước Thượng Đế. Họ là những tên què gánh tội, Lamed Wufniks. Họ không biết nhau, và rất ư là nghèo khổ. Nếu có 1 tên biết rằng mình là tên què gánh tội, là bèn lập tức, ngỏm củ tỏi. Và một người khác, có lẽ ở đâu đó trên thế giới, thế chỗ anh ta. Không có 36 tên cà chớn này, là liền lập tức, Thượng Đế xóa sổ thế giới. http://www.tanvien.net/TG2/tg2_camus_ke_la.html

The, Elephant

That Foretold the Birth of the Buddha

Five centuries before the Christian era, Queen Maya, in Nepal, had a dream

that a white Elephant, which dwelled on the Golden Mountain, had entered

her body. This visionary beast was furnished with six tusks. The King's soothsayers

predicted that the Queen would bear a son who would become either ruler of

the world or the savior of mankind. As is common knowledge, the latter came

true. In India the Elephant is a domestic animal. White stands for humility

and the number six is sacred, corresponding to the six dimensions of space:

upward, downward, forward, back, left, and right. A Crossbreed

I have a curious animal, half-cat, half-lamb. It is a legacy from my father. But it only developed in my time; formerly it was far more lamb than cat. Now it is both in about equal parts. From the cat it takes its head and claws, from the lamb its size and shape; from both its eyes, which are wild and changing, its hair, which is soft, lying close to its body, its movements, which partake both of skipping and slinking. Lying on the window-sill in the sun it curls itself up in a ball and purrs; out in the meadow it rushes about as if mad and is scarcely to be caught. It flies from cats and makes to attack lambs. On moonlight nights its favorite promenade is the tiles. It cannot mew and it loathes rats. Beside the hen-coop it can lie for hours in ambush, but it has never yet seized an opportunity for murder. I feed it on milk; that seems to suit it best. In long draughts it sucks the milk into it through its teeth of a beast of prey. Naturally it is a great source of entertainment for children. Sunday morning is the visiting hour. I sit with the little beast on my knees, and the children of the whole neighborhood stand round me. Then the strangest questions are asked, which no human being could answer: Why there is only one such animal, why I rather than anybody else should own it, whether there was ever an animal like it before and what would happen if it died, whether it feels lonely, why it has no children, what it is called, etc. I never trouble to answer, but confine myself without further explanation to exhibiting my possession. Sometimes the children bring cats with them; once they actually brought two lambs. But against all their hopes there was no scene of recognition. The animals gazed calmly at each other with their animal eyes, and obviously accepted their reciprocal existence as a divine fact. Sitting on my knees the beast knows neither fear nor lust of pursuit. Pressed against me it is happiest. It remains faithful to the family that brought it up. In that there is certainly no extraordinary mark of fidelity, but merely the true instinct of an animal which, though it has countless step-relations in the world, has perhaps not a single blood relation, and to which consequently the protection it has found with us is sacred. Sometimes I cannot help laughing when it sniffs round me and winds itself between my legs and simply will not be parted from me. Not content with being lamb and cat, it almost insists on being a dog as well. Once when, as may happen to anyone, I could see no way out of my business difficulties and all that depends on such things, and had resolved to let everything go, and in this mood was lying in my rocking-chair in my room, the beast on my knees, I happened to glance down and saw tears dropping from its huge whiskers. Were they mine, or were they the animal's? Had this cat, along with the soul of a lamb, the ambitions of a human being? I did not inherit much from my father, but this legacy is worth looking at. It has the restlessness of both beasts, that of the cat and that of the lamb, diverse as they are. For that reason its skin feels too narrow for it. Sometimes it jumps up on the armchair beside me, plants its front legs on my shoulder, and puts its muzzle to my ear. It is as if it were saying something to me, and as a matter of fact it turns its head afterwards and gazes in my face to see the impression its communication has made. And to oblige it I behave as if I had understood and nod. Then it jumps to the floor and dances about with joy. Perhaps the knife of the butcher would be a release for this animal; but as it is a legacy I must deny it that. So it must wait until the breath voluntarily leaves its body, even though it sometimes gazes at me with a look of human understanding, challenging me to do the thing of which both of us are thinking. FRANZ KAFKA: Description of a Struggle (Translated from the German by Tania and James Stern) Jorge Luis Borges: The Book of Imaginary Beings I have a curious animal, half-cat, half-lamb. It is a legacy from my father: Tôi có 1 con vật kỳ kỳ, nửa mèo, nửa cừu. Nó là gia tài để lại của ông già của tôi Không phải ngẫu nhiên mà Gregor Samsa thức giấc như là một con bọ ở trong nhà bố mẹ, mà không ở một nơi nào khác, và cái con vật khác thường nửa mèo nửa cừu đó, là thừa hưởng từ người cha. Walter Benjamin Perhaps the knife of the butcher would be a release for this animal; but as it is a legacy I must deny it that. So it must wait until the breath voluntarily leaves its body, even though it sometimes gazes at me with a look of human understanding, challenging me to do the thing of which both of us are thinking. Có lẽ con dao của tên đồ tể là 1 giải thoát cho con vật, nhưng tớ đếch chịu như thế, đối với gia tài của bố tớ để lại cho tớ. Vậy là phải đợi cho đến khi hơi thở cuối cùng hắt ra từ con vật khốn khổ khốn nạn, mặc dù đôi lúc, con vật nhìn tớ với cái nhìn thông cảm của 1 con người, ra ý thách tớ, mi làm cái việc đó đi, cái việc mà cả hai đều đang nghĩ tới đó!

|