Self

Portrait

Subject

Brodsky

Tưởng

Niệm Czeslaw Milosz [1911-2004]

Old

Marx

Our

World

Trong căn phòng nhỏ

Reading Milosz

Greene House

1

2

3

|

OUR WORLD

IN

MEMORIAM W. G. SEBALD

I never met him, I only knew

his books and the odd photos, as if

purchased in a secondhand shop, and human

fates discovered secondhand,

and a voice quietly narrating,

a gaze that caught so much,

a gaze turned back,

avoiding neither fear

nor rapture;

and our world in his prose,

our world, so calm-but

full of crimes perfectly forgotten,

even in lovely towns

on the coast of one sea or another,

our world full of empty churches,

rutted with railroad tracks, scars

of ancient trenches, highways,

cleft by uncertainty, our blind world

smaller now by you.

One Response to “The

Perfect Present for

Sebald Readers

- Ivo Kievenaar Says:

February 8, 2009 at 8:14 am

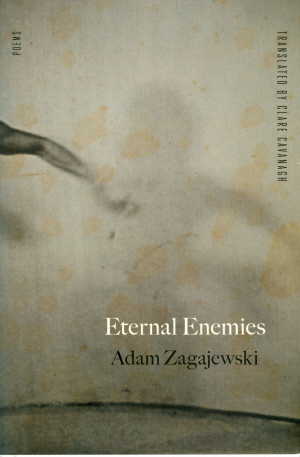

I just bought: Adam Zagajewski / Eternal enemies, a marvelous

book of poems, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008. One of the poems is

dedicated to W.G. Sebald.

Trang

thơ Adam Zagajewski

Letter from a Reader

Too much

about death,

too many shadows.

Write about life,

an average day,

the yearning for order.

Take the

school bell as your model

of moderation,

even scholarship.

Too much

death,

too much

dark radiance.

Take a look,

crowds packed

in cramped stadiums

sing hymns of hatred.

Too much

music

too little harmony, peace,

reason.

Write about

those moments

when friendship's foot-bridges

seem more enduring

than despair.

Write about

love,

long evenings,

the dawn,

the trees,

about the endless patience

of the light.

Adam Zagajewski

Dịch từ tiếng Ba Lan: Clare Cavanagh

*

Từ một

độc giả Tin Văn

Đen

thui,

Ngoại

trừ

những dòng

Về

BHD

Quá

nhiều về

chết chóc

Quá

nhiều bóng

tối

Hãy

viết về

cuộc đời

một

ngày,

khoảng đó,

khát

khao trật

tự

Adam

Zagajewski

OLD MARX

He can't think. London

is damp,

in every room someone coughs.

He never did like winter.

He rewrites past manuscripts

time and again, without passion.

The yellow paper

is fragile as consumption.

Why does life race

Stubbornly toward

destruction?

But spring returns in dreams,

with snow that doesn't speak

in any known tongue.

And where does love fit

within his system?

Where you find blue flowers.

He despises anarchists,

idealists bore him.

He receives reports from Russia,

far too

detailed.

The French grow rich.

Poland

is

common and quiet.

America

never stops growing.

Blood is everywhere,

perhaps the wallpaper needs

changing.

He begins to suspect

that poor humankind

will always trudge

across the old earth

like the local lunatic

shaking her fists

at an unseen God.

[Eternal

Enemies p.67]

OLD MARX (2)

I try to

envision his last winter,

London, cold and

damp, the snow's curt kisses

on empty streets, the Thames' black water.

Chilled prostitutes lit bonfires in the park.

Vast locomotives sobbed somewhere in the night.

The workers spoke so quickly in the pub

that he couldn't catch a single word.

Perhaps Europe was richer and at peace,

but the Belgians still tormented the Congo.

And Russia? Its tyranny? Siberia?

He spent evenings staring at the shutters.

He couldn't concentrate, rewrote old work,

reread young Marx for days on end,

and secretly admired that ambitious author.

He still had faith in his fantastic vision,

but in moments of doubt

he worried that he'd given the world only

a new version of despair;

then he'd close his eyes and see nothing

but the scarlet darkness of his lids.

-Adam Zagajewski

(Translated,from the

Polish, by Clare Cavanagh.)

[The New Yorker, Jan 21, 2008]

[Eternal Enemies p. 97]

Cụ Mác

Tôi cố tưỏng tượng ra mùa đông

cuối cùng

của ông,

Luân Đôn, lạnh, ẩm.

Tuyết đè ngửa, hôn tàn bạo lên phố vắng, lên mặt nước đen thui của dòng

sông Thames.

Bướm co ro, run rẩy nhóm lửa nơi công viên.

Có tiếng sụt sùi của những đầu máy, ở đâu đó trong đêm.

Những người thợ nói quá nhanh trong tiệm rượu,

khiến ông không kịp bắt, dù chỉ một từ.

Có lẽ Âu Châu thì giầu có hơn, và thanh bình,

nhưng người Bỉ vẫn hành hạ xứ Congo.

Còn Nga xô thì sao? Bạo chúa của nó? Siberia,

chốn lưu đầy ư?

Ông trải qua những buổi tối mắt

dán lên

những tấm màn cửa.

Ông không thể nào tập trung, viết lại những tác phẩm đã xưa, cũ,

đọc lại Marx trẻ cho tới hết ngày,

và thầm lén ngưỡng mộ tay tác giả tham vọng này.

Ông vẫn còn niềm tin ở cái viễn ảnh thần kỷ, quái đản của mình,

nhưng vào những lúc hồ nghi,

ông đau lòng vì đã đem đến cho thế giới,

chỉ một viễn ảnh mới của sự thất vọng, chán chường;

rồi ông nhắm mắt và chẳng nhìn thấy gì nữa, ngoài bóng tối của mí mắt

của mình.

*

READING

MILOSZ

I read your poetry once more,

poems written by a rich man, understanding all,

and by a pauper, homeless, an emigrant, alone.

You always want to say more

than we can, to transcend poetry, take flight,

but also to descend, to penetrate the place

where our timid, modest realm begins.

Your voice at times persuades us,

if only for a moment,

that every day is holy

and that poetry, how to put it, rounds our life,

completes it, makes it proud

and unafraid of perfect form.

I lay the book aside

at night and only then the city's normal tumult starts again,

somebody coughs or cries, somebody curses.

-Adam Zagajewski (Translated from the Polish by Clare Cavanagh)

The New York

Review, 1 March, 2007.

[Eternal Enemies

p. 40]

Đọc Milosz

Tôi đọc thơ ông,

thêm

một lần nữa,

những

bài thơ viết bởi một người giầu có, thông tuệ,

và

bởi một người nghèo mạt hạng, không nhà cửa, di dân, cô độc.

Ông

luôn muốn nói nhiều hơn

chúng

tôi có thể nói,

để

chuyển hóa thơ, để cất cánh,

nhưng

cũng để hạ cánh, dấn sâu vào khoảng đất

nơi

cõi đời của chúng ta, dụt dè, chơn chất, bắt đầu.

Tiếng

nói của ông, nhiều lần, chỉ trong một khoảnh khắc,

khiến

chúng tôi ngộ ra một điều là,

mỗi

ngày, một ngày, mọi ngày, thì thiêng liêng.

và

rằng, thơ, thể hiện điều đó, bằng cách,

quanh

quẩn bên đời ta,

hoàn

tất nó, làm cho nó tự hào, hãnh diện,

và,

đâu cần một dạng hoàn hảo nào, cho thơ.

Tôi

để cuốn sách qua một bên.

Đêm,

và chỉ tới lúc đó, cái xô bồ, thường lệ, của thành phố lại khởi

động,

một

người nào đó ho, hay là, la khóc, một người nào đó, nguyền rủa.

Adam

Zagajewski

STAR

I returned to you years

later,

gray and lovely city, unchanging city,

buried in the waters of the

past.

I'm no longer the student

of philosophy, poetry, and

curiosity,

I'm not the young poet who wrote

too many lines

and wandered in the maze

of narrow streets and

illusions.

The sovereign of clocks and

shadows

has touched my brow with his hand,

but still I'm guided by

a

star by brightness

and only brightness

can undo or save me.

Bài thơ

trên, tả cảnh Gấu trở

về Hà Nội.

Gấu phóng dịch:

Ta trở

về với mi, nửa thế kỷ

sau,

Thành phố xám xịt, đáng yêu,

và chẳng có gì thay đổi

Chôn dưới những con nước của

những con hồ Bẩy Mẫu, Thuyền Cuông, Hồ Gươm, Hồ Tây

Ta đâu

còn là chàng sinh viên

của triết học, của thơ ca, và của tò mò

Cũng không còn là nhà thơ trẻ

viết rất nhiều dòng thơ

và lang

thang trong mê cung

của những con phố hẹp và của

những ảo tưởng

Chúa Cả Ngôi Cao, với những cái

đồng hồ và những cái bóng của nó,

Thò cánh tay xuống, chạm vào lông

mày của ta

Nhưng

ta vẫn được dẫn dắt bởi

một ngôi sao, bởi sự sáng ngời

Và chỉ sự sáng ngời

Là có thể làm lại, hay, cứu vớt

đời ta.

Chúa Cả

Ngôi Cao, là Gấu muốn

nói tới Nhà Thờ Hà Nội, khu Nhà Chung, trường Dũng Lạc... ở kế

bên Bờ Hồ.

Bài thơ, đọc song song với

bài thơ Những con phố sau của Hà Nội,

thì mới đã.

Những con phố

sau của Hà Nội

Nhà trại thui thủi, chẳng cần

Gấu

Và con chó già của Gấu thì lùi lũi chuồn ra khỏi cửa

Chúa biểu Gấu, thôi, hãy về chết ở trong những con phố sau.

Và Gấu tôi không có thể về nhà được nữa.

Gấu thì yêu đến khốn khổ khốn

nạn cái

thành phố quá chớn này.

Nó thì mới dơ dáy, bệ rạc làm sao.

Và làm Gấu nhớ đến những câu chuyện cổ tích ru giấc ngủ ngày nào

Và những âm thanh của con phố làm tim Gấu đau nhói.

Quá nửa đêm, Gấu đi ra ngoài

kiếm một cái

gì đó cho đỡ khổ

Và cái mà Gấu kiếm đó, là danh vọng.

Thế là Gấu đi đến một quán rượu ở những con phố sau.

Nơi ai cũng biết tên Gấu.

Ồn, dơ, say, và, xỉn.

Nhưng chẳng ai độc ẩm ở đó.

Ở những con phố sau của Hà Nội.

Mấy tay bồi riệu mua cuốc lủi cho Gấu,

Mấy chị em ta khóc ròng khi nghe đọc thơ của Gấu

Tim Gấu đập, mỗi lúc một nhanh

thêm

Và Gấu nói với tên say gần bên cửa –

“Ta thì cũng như mi thôi, đời ta là một thảm họa

Và ta không thể trở về nhà được nữa.”

Nhà trại thui thủi, chẳng cần

Gấu, cũng

thui thủi

Và con chó già của Gấu thì lùi lũi chuồn ra khỏi cửa

Chúa biểu Gấu, thôi, hãy về chết ở trong những con phố sau.

Và Gấu không có thể về nhà được nữa.

THE

BACK STREETS OF MOSCOW

Ui chao, hồi này già quá, cơ thể rệu rạo, hệ thống miễn nhiễm hết còn

OK,

thành thử con vai rớt Bắc Kít

hoành hành, đáng sợ thực! NQT

POETRY

Light in the grime

JON STALLWORTHY

Adam Zagajewski

ETERNAL ENEMIES

Translated by Clare Cavanagh

116pp. Farrar, Straus and

Giroux. Paperback, $14. 9780374531607

Adam

Zagajewski's "Try

to praise the mutilated world", first published in the post-September

11

"black" issue of the New Yorker, takes its title from its opening

line:

Try to praise the mutilated

world.

Remember June's long days,

and wild strawberries, drops

of rose wine.

The nettles that methodically

overgrow

the abandoned homesteads of

exiles.

You must praise the mutilated

world.

You watched the stylish

yachts and ships;

one of them had a long trip

ahead of it,

while salty oblivion awaited

others.

You've seen the refugees

going nowhere,

you've heard the executioners

sing joyfully.

You should praise the

mutilated world.

Remember the moments when we

were together

in a white room and the

curtain fluttered.

Return in thought to the

concert where music

flared.

You gathered acorns in the

park in autumn

and leaves eddied over the

earth's scars.

Praise the mutilated world

and the gray feather a thrush

lost,

and the gentle light that

strays and vanishes

and returns.

When I read it I was struck,

first, by an awareness that, far from lecturing his reader, the speaker

was

speaking to himself; his use of "You" (a Zagajewski trademark) a

welcome change from the self-important I-deology of so many

contemporary poets.

It struck me, then, that he had brilliantly obeyed his own imperatives

-

"Remember .... Remember .... Return .... Praise" - and had made me do

the same. More generally, I was arrested by the authority of the voice,

the

courage and wisdom of a call to praise in a time (like any other) of

mutilation: praise, a word with Christian associations, repeated with

increasing urgency in the refrain, acquiring the force of a liturgical

response, a prayer. Behind the distinctive new voice, one can hear a

voice

heard in Auden's "Musée des Beaux Arts" ("About suffering they

were never wrong / The Old

Masters"), juxtaposing "miraculous birth" with "dreadful martyrdom"

in which "the torturer" plays a part. At some level, Zagajewski

remembers this as well as his own love, a fluttering curtain (in a

window Auden

had opened), and a "mutilated world" where "the executioners

sing joyfully". Surely, too, Auden's "expensive delicate ship"

must be one of Zagajewski's "stylish ships" - perhaps one heading for

the "salty oblivion" that awaits Icarus in the Bruegel painting on

which Auden's poem is based.

Zagajewski's praise poem has

the variable line-length of Auden's which, despite its unobtrusive

rhymes,

gives it the easy assurance of the best free verse; and one cannot l

pay Clare

Cavanagh a greater compliment than to say her English poem does not

suffer by

comparison with Auden's. These poems have a similarly antithetical

structure: Auden's

moving from birth to death to life continuing; Zagajewski's, from

"June's

long days" to "light that strays and vanishes / and returns".

They tell us "we must praise" the life continuing, the light

returning. They are both Christian poets, intimately involved in human

tragedy,

yet endowed with the detached perspective of the Old Masters.

Adam Zagajewski was born

sixty-four years ago in Lvov and went

to

university in Cracow,

two cities he loves and celebrates in his essays and poems. He

emigrated to France

in 1982 and now lives between Cracow, Paris and Chicago. Early

collections ( of his poems in English translation were presented in

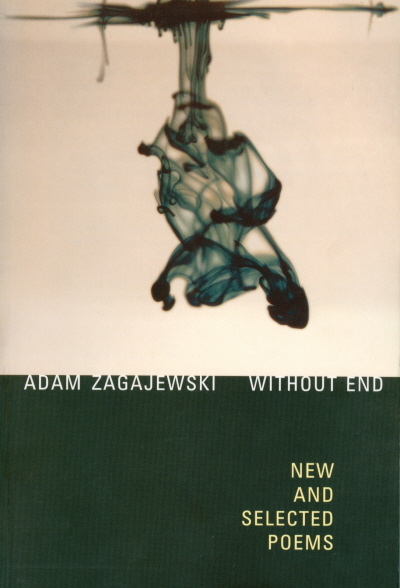

Without End

(2002) - a title echoing the Book of Common Prayer - with a section of

New

Poems translated by Cavanagh. She has achieved something just as

remarkable with

Eternal Enemies. These are identified in n "Epithalamion", a poem

beginning "Without a silence there would be no music", that goes on

to assert: "Only in marriage do love and time, eternal enemies, join

forces". An earlier poem, "Little Waltz", ends: "love sets

us free, time kills us". The coming together of man and woman is imaged

in

that of the earth and "The Sea",

In love with the earth,

always drawn to shore

….

In love with the earth,

thrusting into cities, Stockholm,

Venice, listening to tourists laugh and chatter

before returning to its dark,

unmoving source.

The most frequent pairing and

dis-pairing of the many antitheses in these

poems are those a of light and darkness (themselves linked to a life

and

death), often in a religious context, as a in "The Churches of

France", described as "dark vessels, where the shy flame of mighty

light wanders". Again, in a more a: recent poem, "At the Cathedral's

Foot",

[we] spoke softly about

disasters,

about what lay ahead, the

coming fear,

and someone said this was the

best

we could do now -

to talk of darkness in that

bright shadow.

Such poems remind us that

when this Polish Roman Catholic Adam was born, "the pock- marked /

Georgian

still lived and reigned". With a bitter parody of the opening of St John's

Gospel, he now

remembers:

In the beginning, freezing

nights and hatred.

Red Army soldiers fired

automatic pistols

at the sky, trying to strike

the Highest Being.

The title of that poem,

"Life is Not a Dream", is echoed by the end of the next, "It

Depends": "I push" through a dense thicket of onlookers and ask:

/ What's happening? God's coming back. But it's just a dream".

Zagajewski resembles Yeats in

the skill with which he links poem to poem, so that the power of both

poets'

collections is greater than the sum of individual poems. The Arch-poet

liked to

quote Blake: "Without contraries is no progression". Zagajewski would

agree but, whereas the Irish agnostic celebrated the conflict of

contraries

that, in his "System", made the world and history go round, the

Christian Pole seeks and celebrates harmony, love: "Remember the

moments

when we were together". The title of a key poem proclaims his creed,

"Poetry Searches for Radiance", the creed of creative artists (made

in their Creator's image) such as Blake-

I watch William Blake, who spotted

angels

every day in treetops

and met God on the staircase

of his little house and found

light in grimy

alleys –

and like others whom he

celebrates: Milosz and Brodsky, Caravaggio and Vermeer, Bach and

Schubert.

Last but not least, the

composers: indeed, Zagajewski would seem to believe that life as well

as art

"aspires to the condition of music". A sentence borrowed from Conrad

Aiken - "Music I heard with you was more than music" - finds its way

into three poems of his new book; and music in some form is the means

of

communication/communion in the joyful epiphanic moments to which he and

his

fellow makers aspire. The music of the translator's English free verse,

in its

happy marriage to the poet's European themes, makes Cavanagh's

Zagajewski as rare

and rewarding an experience as that of Milosz's Englished Collected

Poems.

TLS Dec 4 2009

TLS điểm tập thơ Eternal Enemies,

Những kẻ thù thiên thu, của Adam

Zagajewski.

Chắc

bạn còn nhớ dòng thơ của

Brodsky:

Bao thơ tôi, ít nhiều chi, là

về cùng một điều - về Thời Gian. Về thời gian làm gì con người.

"All my poems are more

or less about the same thing – about Time. About what time does to Man."

Đây là câu trả lời của Adam

Zagajewski:

"Only in marriage do

love and time, eternal enemies, join forces"

"love sets us free, time

kills us".

Adam

Zagajewski

Giáng

Sinh, ngồi nhà đọc chơi vài bài thơ!

NEW YEAR’S EVE, 2004

You're at home listening

to recordings of Billie

Holiday,

who sings on, melancholy,

drowsy.

You count the hours still

keeping you from midnight.

Why do the dead sing peacefully?

while the living can't free

themselves from fear?

Adam

Zagajewski

Đêm Giao Thừa

Bạn ở nhà nghe Duy Khánh ca

Xuân này con không về

Bạn đếm từng giờ,

Chờ cúng giao thừa

Tại sao người chết ca nghe thật

hiền hòa?

Trong khi người sống không thể

nào rũ ra khỏi sự sợ hãi?

ANECDOTE OF RAIN

I was strolling under the

tents of trees

and raindrops occasionally

reached me

as though asking:

Is your desire to suffer,

to sob?

Soft air, wet leaves;

-the scent was spring, the

scent sorrow.

Giai thoại

mưa

Anh lang thang dưới tàng cây

và những hạt mưa thỉnh thoảng

lại đụng tới anh

như muốn hỏi:

thèm gì, ước gì?

đau khổ

hay nức nở?

Trời nhẹ, lá ướt;

-Mùi xuân, mùi buồn

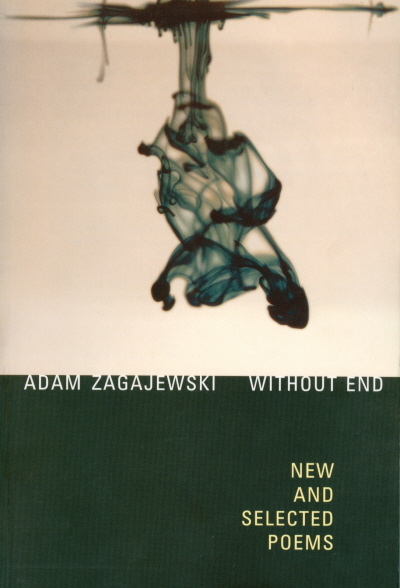

"His

poems celebrate

those rare moments when we catch a glimpse of a world from which all

labels

have been unpeeled."

-Charles Simic, The New York

Review of Books

"Seldom has the muse of

poetry spoken to anyone with such clarity and urgency," wrote Joseph

Brodsky, "as in Zagajewski's case." Without End draws from each of

Adam Zagajewski's English-language collections, both in and out of

print- Tremor,

Canvas, and Mysticism for Beginners-and features new work that is among

his

most refreshing and rewarding. In lucid translations by Clare Cavanagh,

Renata

Gorczynski, Benjamin Ivry, and C. K. Williams, these poems share the

vocation

that allows us, in Zagajewski's words, "to experience astonishment and

to

stop still in that astonishment for a long moment or two."

"These poems enter and

possess you quietly. It is the quiet of a train halted on its lines.

The engine

throbs like a pulse, and there is always music in these verses, or the

echo of

music ... His is the quiet voice at the corner of the immense

devastations of

an obscene century, more intimate than Auden, yet as cosmopolitan as

Milosz,

Celan, or Brodsky."

- Derek Walcott, The New

Republic

"Filled with splendid

moments of spiritual lucidity ... [These poems] transport us into a

realm that

is majestic, boundless and unknown."

-Edward Hirsch, The Washington

Post Book

World

"Zagajewski's poems pull

us from whatever routine threatens to dull our senses, from whatever

might lull

us into mere existence. This is an astonishing book." -Philip Boehm,

The

New York Times Book Review

Những

ngày Noel, Gấu ngồi nhà

“đọc chơi” [chữ của nhà đại phê bình] ba nhà thơ, mong tìm ra cái

chung, và cái

riêng của mỗi người.

Một, nữ thi sĩ Mít, một nữ

thi sĩ và một nam thi sĩ Ba Lan.

Thâu hoạch cũng không tệ.

Adam

Zagajewski

Thơ của

ông ngợi ca những khoảnh

khắc, khi chúng ta thoáng nắm bắt một thế giới mà mọi nhãn hiệu dán lên

nó đều là

nhảm cả.

-Charles Simic, The New York Review of Books

“Thật hiếm hoi, nàng thơ nói,

với bất cứ ai, rõ ràng như thế, khẩn trương như thế, như là trong

trường hợp

Zagajewski,” Brodsky viết. “Không tận

cùng, lọc ra từ những tập có trước đó, có

những tập đã tuyệt bản, như Trémor,

Canvas, Mysticism for Beginners, ngoài ra còn những bài thơ mới,

trong số

những bài tươi mát, hách nhất, bảnh nhất của ông. Qua những bản dịch

thật sáng

suốt của Clare Cavanagh, Renata Gorczynski, Benjamin Ivry, và C. K.

Williams, …

những bài thơ chia sẻ một thiên hướng, nó cho phép chúng ta, qua những

từ của

Zagajewski, ‘kinh nghiệm sự kinh ngạc, và đứng sững trong kinh ngạc,

trong một

khoảnh khoắc, một chốc lát. Hoặc lâu hơn tí nữa: hai chốc lát’.”

Giáng

Sinh, ngồi nhà đọc chơi vài bài thơ!

Một đóng góp

cho ngành thống

kế

Trong số 100 người

những người luôn luôn hiểu biết,

bảnh hơn người khác

- 52 mạng

nghi ngờ, từng bước chân

- gần như hết, số còn lại

vui mừng vì đưa tay ra,

nếu chuyện đó không mất công,

- 49, nhỉnh hơn một tí

luôn luôn tốt

bởi vì không thể làm khác

- 4 đấng, ồ, may ra có thể 5

có thể ngưỡng mộ,

mà không thèm

muốn, hay ghen tị,

-18 mống

đau khổ vì ảo tưởng

tuổi trẻ qua quá nhanh

- 60, hơn, hoặc kém, một tí

không coi nhẹ chuyện đời

- 40 mạng, thêm 4 mạng

luôn sống trong sợ hãi

một kẻ nào đó, hay một chuyện

gì đó

- 77 mạng

có thể hạnh phúc

hai chục, cỡ đó, ở trên đỉnh

từng cá nhân vô hại, hoang dại

giữa đám đông

- nửa con số trên, ít ra là vậy

độc ác khi hoàn cảnh bắt buộc

- tốt nhất, đừng nên biết

dù con số đại khái

khôn ngoan, sau

sự kiện

-

chỉ vài cặp khôn

ngoan hơn trước

chỉ lấy sự kiện từ đời sống

- ba chục

(tôi mong mình lầm)

còng lưng vì nỗi đau

không ánh sáng loé lên trong

bóng tối

- tám muơi ba

sớm hay muộn

ngay thẳng

- ba muơi lăm, vậy là quá nhiều

ngay thẳng và hiểu biết

- ba

đáng thông cảm

- chín mươi ba

ngỏm

- một trăm phầm trăm

con số này cho tới nay chưa

thay đổi

WISLAWA

SZYMBORSKA

[Nobel

văn chương]

Stanislaw

Baranczak

và Clare

Cavanagh

dịch

từ tiếng Ba Lan

Partisan

Review

1998

|