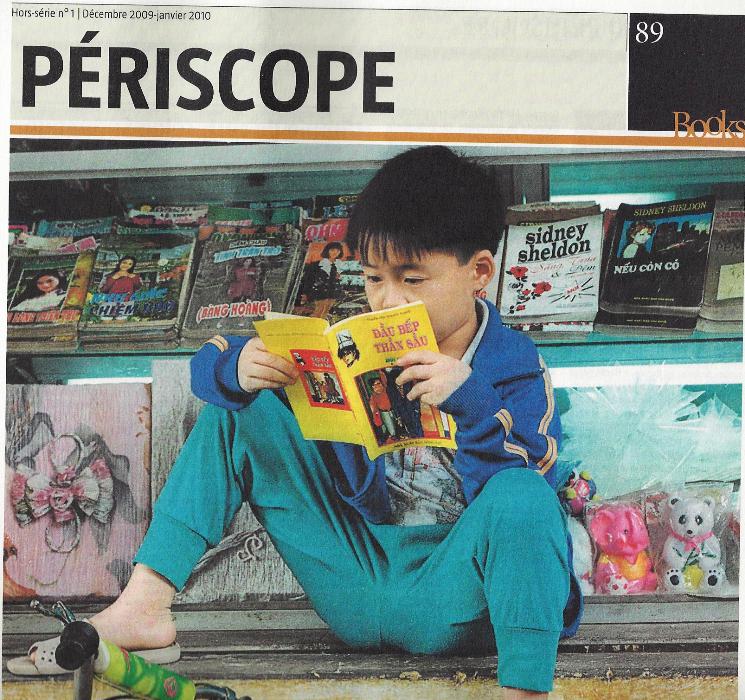

Trang Thiếu Nhi

|

Something

Wonderful Out of Almost Nothing

Một điều gì

tuyệt vời bò ra từ chẳng có gì!

Anh Cu Tí mắc cái bịnh, kể như

là bịnh xấu tính, mà theo những nhà tâm lý học,

có thể là do xì-trét, đì-prét, hoặc do buồn

quá, đếch có bạn chơi.

Nó vứt tình yêu của bố mẹ vô thùng rác:

Một bữa má nó nói

Khi Cu Tí vừa bỏ ra khỏi

giường

Chào Cu Tí cưng của má

Cu Tí bèn buông một

câu,“Con đếch cần!”

Cũng bằng 1 cách cáu giận như

thế, cu cậu lắc đầu trước mọi dụ dỗ

của bà mẹ.

Bất cứ ai nói cái gì, đưa cho cái gì, là Anh Cu Tí phán,“Ta đếch cần”!

Và khi bố mẹ đi làm, một con "sử tử đói" xuất hiện:

Nó nhìn vào

tận mắt Cu Tí

Và hỏi, mi muốn sống hay muốn chết?

Anh Cu Tí buông 1 câu, “Tao đếch cần”!

Thế

là nó bèn xơi tái Anh

Cu Tí!

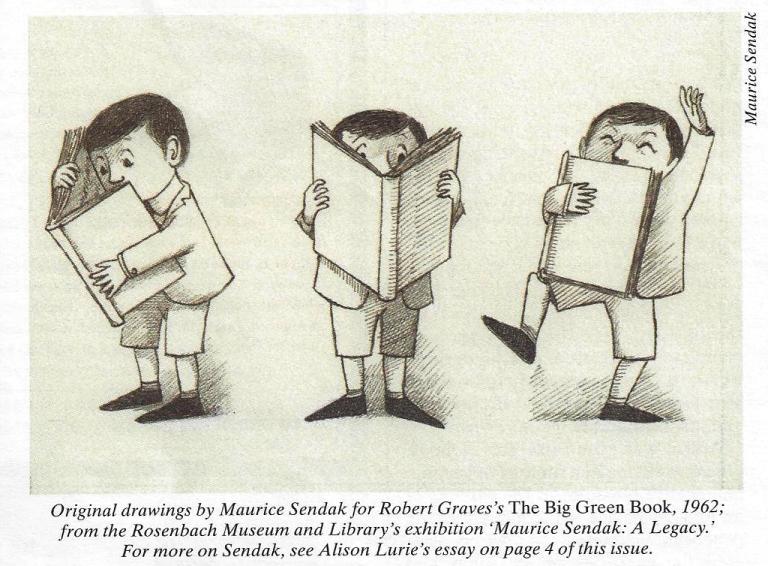

Something

Wonderful Out of Almost Nothing

Alison Lurie

Only a few

people have been both great writers and great illustrators of

children's books.

In the nineteenth century there was Edward Lear, and in the twentieth

Dr. Seuss

and – perhaps the most gifted of them all – Maurice Sendak, who died in

May at

the age of eighty-three.

Sendak's

best-known work, Where the Wild

Things Are (1963), shocked some adult readers

at first; later it was recognized as a brilliant breakthrough. It gave

graphic

expression to what every parent knows - that kids are sometimes angry

and even

violent; and it proposed that these impulses could be explored and

enjoyed

rather than repressed and denied. Within a few

years Where the Wild Things Are

was a recognized classic. It wasn't a fluke:

the same originality and psychological insight was already evident in

Sendak's

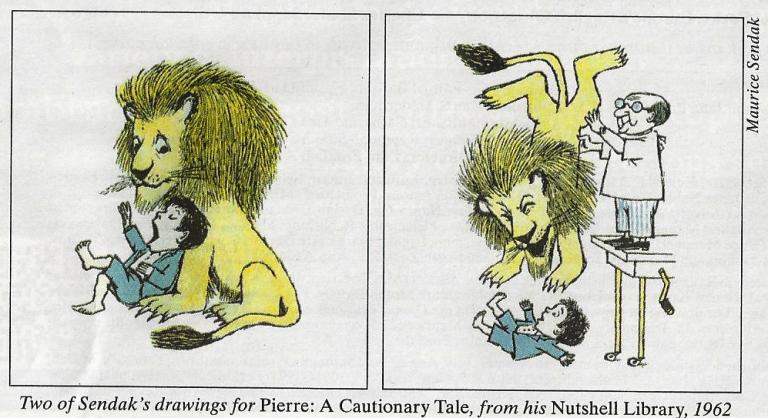

earlier work, most notably perhaps in Pierre: A Cautionary Tale, the

best of

the four tiny books (each less than 3 by 4 inches) in his Nutshell

Library (1962).

The classic

cautionary tale is a story, often in verse, in which a child misbehaves

and is

severely punished. Usually the tone is

exaggerated and comic, but it can also be frightening. In Heinrich

Hoffmann's Struwwelpeter (1845), which terrified

generations of kids, a little boy who

sucks his thumbs gets them cut off by giant scissors. Hilaire Belloc's Cautionary Tales (1907) are lighter in

tone, but they follow the standard plot of bad behavior and awful

retribution.

(1) As usual in such tales, adult friends and relatives utter warnings,

but they

don't do anything to protect the child or seem very upset by what

happens. In

Belloc's "Jim, who ran away from his Nurse, and was eaten by a Lion,"

his mother merely remarks afterward:

"Well-it gives me no

surprise,

He would not do as he was told!"

His Father, who was self-

controlled

Bade all the children round attend

To James's miserable end,

And always keep a-hold of Nurse

For fear of finding something worse.

This is a

joke, of course, but not a very pleasant one.

Philadelphia,

June 10, 2012-May 26, 2013

***

Sendak's

Pierre suffers from what looks like bad temper and sulkiness, but could

be the

kind of apathy that, according to psychologists, is one of the symptoms

of

depression. He rejects his parents' love:

One day his mother said

when Pierre climbed out of bed,

"Good morning, darling boy,

you are my only joy."

Pierre said, "I don't

care!"

With

similar

angry indifference, Pierre responds to offers of cream of wheat with

syrup and

a trip to town. No matter what anyone says, he replies, "I don't

care!" After his parents leave, "a hungry lion" appears:

He looked Pierre right in

the eye

and asked him if he'd like to die.

Pierre said, "I don't care!

"

...

"Is that all you have to

say?"

"I

don't care! "

"Then I'll eat you, if I

may."

"I

don't care! "

So the lion ate Pierre.

When his

parents get home they find the lion sick in Pierre's bed. Unlike Jim's

parents,

they do not accept this with equanimity:

They pulled the lion by

the hair.

They hit him with the folding

chair.

His mother asked, "Where is

Pierre?"

The lion answered, "I don't

care!"

His father said, "Pierre's

in

there!"

There

are

several ways of understanding this. One is that the incorporation,

physical or

psychological, of hostile, unpleasant persons can make you ill. It may

also be

that the lion, like Max's Wild Things in Where the Wild Things Are, is an

emanation from Pierre's psyche, or Pierre turned inside out. It would

be a

mistake to think that Sendak was unaware of these possibilities, or of

the

psychological sophistication of his story. After all, he lived with the

child

psychiatrist Eugene Glynn for fifty years-until Glynn's death in 2007

at the

age of eighty-one.

Unlike most

earlier cautionary tales, Pierre has a happy ending. The parents take

the lion

to a doctor, who turns him upside down, and Pierre falls out:

He rubbed his eyes and

scratched

his head and laughed because he

wasn't

dead.

***

The lion

looks happier too; he goes home with Pierre and his family, and stays

on

"as a weekend guest." As in Where the Wild Things Are, disruptive

impulses

are not rejected or suppressed, but accepted and incorporated into real

life,

though within limits: the lion visits but does not join the family.

Pierre is

not punished, but saved. As Sendak says at the end:

The moral of Pierre

is CARE! (2)

***

A brilliant

illustrator can transform any story, revealing its possible meanings

and

sometimes changing them. Alice

in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass would

be less

scary without John Tenniel's drawings (especially those of the Duchess

and the Jabberwocky),

and Winnie-the-Pooh less

lovable without the help of Ernest Shepard. Maurice

Sendak brought his artistic talents to over seventy works by other

writers,

always making them more interesting.

Most popular

illustrations of the Grimms' fairy tales, for instance, soften and

prettify

them. Sendak turns them into crowded dreams full of strange birds and

beasts,

in which there is understanding for the villains, including the

crippled witch

in "Hansel and Gretel" and Snow-White's stepmother with her fading

beauty and fixed stare. He also notably illustrated three collections

of tales

by Isaac Bashevis Singer with drawings full of wise animals and flying

demons

that heighten their fantastic side and recall the paintings of Marc

Chagall.

As well as

interpreting classic tales, Sendak could make something wonderful out

of almost

nothing. In We Are All in the Dumps

with Jack and Guy (1993), for instance, he transforms two old British

non-sense

rhymes into a tale about homelessness, crime, and charity. His pictures

make it

clear that the story takes place in New York, and that the first lines

can be

understood in different ways:

We are all in the dumps

For diamonds are trumps

Sendak's

characters are both depressed and living in a kind of abandoned dump.

Evil-looking rats are cheating at cards, and the Trump Tower and a

huge,

worried-looking moon rise above a city where money triumphs over

everything.

Lost children shelter in cardboard boxes or huddle under pages of The New York Times full of ads for cheap

mortgages and news of lost jobs.

Presently a

lot of kittens and a little African-American boy are kidnapped by the

rats. But

up in the sky three angels are reading all about it in the newspaper,

and help

is on the way. The moon turns into a huge white cat who rescues the

kittens.

The kidnapped boy escapes and is discovered by two young toughs:

Jack and Guy went out in

the rye

And they found a little

boy with

one black eye

Come says Jack let's

knock him

on the head

No says Guy let's buy him

some

bread

You buy one loaf, and

I'll buy two

And we'll bring him up as other

folk do

The last

picture in the book shows all three of them and other homeless children

asleep

in their urban jungle, surrounded by smiling kittens. Life in the city

is

scary, mean, and precarious, Sendak's pictures tell us, but impulsive

goodness

also exists. There are other possibilities here too: one critic has

interpreted We Are All in the Dumps as, among

other things, a kind of Christian allegory. (3)

One proof

that some work of art is a classic is that each time you revisit it you

see it

differently. When I reread We Are All in

the Dumps this week, I realized that it can also be viewed as a

story about

the interracial adoption, by two males, of an abused and abandoned

child. No doubt

other readers will continue to find new meanings in all of Sendak's

best work,

for many years to come.+

(1) Belloc

also illustrated his own verses, but not always very well.

(2) In an

odd coincidence, over thirty years later Sendak would illustrate

another book

called Pierre: Herman Melville's strange and awkward novel, whose

eponymous

hero is far more conflicted and negative than the earlier Pierre, and

fails to

escape his problems.

(3) See Peter F. Neumeyer,

"We Are All in the Dumps

with Jack and Guy: Two

Nursery

Rhymes with Pictures by Maurice Sendak," Children's Literature in

Education, Vol.25, No 1 (1994)

The NYRB

July 12, 2012

|