|

Họ đợp giấc

ngủ của họ Herta Muller

Even inside the Zeppelin, love had its

seasons. The

wildcat weddings came to end in our second year, first because of the

winter and later because of the hunger. When the hunger angel was

running rampant during the skin-and-bones time, when male and female

could not be distinguished from each other, coal was still unloaded at

the silo. But the path in the weeds was overgrown.

Purple-tufted vetch

clambered among the white yarrow and the red orache, the blue burdocks

bloomed and the thistles as well. The Zeppelin slept and belonged to

the rust, just like the coal belonged to the camp, the grass belonged

to the steppe and we belonged to hunger. _

GRANTA,

Spring, 2010 Note:

Tờ Granta, số mới nhất, sex, có truyện ngắn trên. Và nhất là, làm nhớ cú "sex" ở trại tù Đỗ Hòa! Nhưng

cái xen, hàng đêm Đức Quốc Trưởng phải hì hục tiếp các cháu gái ngoan,

đứng xếp hàng chờ tới lượt, mới thú! Nhớ

nhắc Bác cạo râu đấy nhé: Cháu có mắc

tiểu không? Để Bác chỉ chỗ cho mà tiểu

(1) Cái tay Đại Gìáo Sư VC, [theo ông cậu, Cậu Toàn của GGC, thì hai người cùng promo, hình như cùng lớp], NDM, viện Dos để giải thích “cas” này. Theo GCC,

không phải. Ngày thì Bác

Hát là Thần “Bác” lúc

nào cũng tơ tưởng chuyện đó, cho nên, bất thần, phọt ra. Cũng thế, là cas Bùi Tín,

“Chúng mày còn cái đéo gì nữa mà bàn giao”! Trường hợp Bác

H, GCC cũng đã từng gặp, nhưng không đến nỗi tục tĩu như của Bác. GCC

cũng

đã lèm bèm

đôi lần rồi, và nó liên quan tới cái sẹo ở cổ tay “cô bạn”. Vào những ngày đầu mới tới xứ lạnh, không biết

GCC nghe qua ai kể những ngày đầu khi gia đình của cô được một cơ quan

thuộc

Nhà Thờ bảo lãnh qua, rồi tất tả hội nhập, tất tả kiếm việc, đi

làm, công việc chân

tay chắc

cũng nặng nề, và cái gân ở cổ tay bị nhão, bị chùng, phải giải phẫu… Thế là cứ

mơ tưởng so sánh hoài, bàn tay ngày nào khi còn là nữ sinh viên con nhà

giầu, lỡ

thương đúng thằng chồng cô bạn thân, và bàn tay khi lưu vong... Mơ

tưởng

hoài, thế là đêm nằm, lầm tay vợ đang nằm kế bên với tay cô bạn,

thế là mò

mò cái sẹo

ở cổ tay, chẳng thấy đâu, thế là bèn buột miệng la, như Bác H buột

miệng, cái sẹo

đâu rồi! Ui chao, cái

bà bạn của cả hai bà, từ hồi còn học tiểu học, trường Đốc Binh Kiều,

Cai

Lậy, cái

bà nghe kể "5 năm trời không dám đụng", bèn bĩu môi, làm sao biết ma ăn

cỗ, nhưng

khi nghe kể chuyện cái sẹo thì lại gật gù, giả như mà tui gặp được 1

người đàn ông

thương tui như thế, thì cũng bõ 1 đời nhan sắc! Hà, hà!  NYRB May 24, 2012 điểm Thiên Thần Đói, của Herta Muller. Họ đợp giấc

ngủ của họ Thiên Thần Đói, một tác phẩm tuyệt vời,

sôi nổi, thơ,

được viết - như 1 nhà phê bình phán - bằng máu của trái tim của chính

tác giả. Truyện Tù Xứ Mít thì được viết bằng thơ của Mai-a-cóp-ki! Lạ, là trong

số báo mới này còn đi 1 bài điểm Khi Tôi Hấp Hối, “On ‘As I Lay Dying’”

của

Faulkner. GCC coi lại, đây là lời

giới thiệu ấn bản mới nhất của Khi

tôi hấp hối The Hunger

Angel là bản dịch tiếng Anh của Atemschaukel.

Tuyệt. Đây mới

đúng là hồi ký tù, hồi ký Trại. Nobel

2009

C’est

la fin de la guerre, partout en Europe les prisonniers rentrent chez

eux, les

familles sont à nouveau réunies mais en Roumanie il en va différemment,

les

hasards des derniers combats ont livré le pays aux soviétiques. Les

russes exigent

que tous les citoyens roumains d’origine allemande, qui vivent en

Transylvanie,

soient arrêtés. Certains ont collaboré avec les allemands mais tous les

ressortissants hommes et femmes de 17 à 45 ans sont déportés,

collaboration ou

pas.

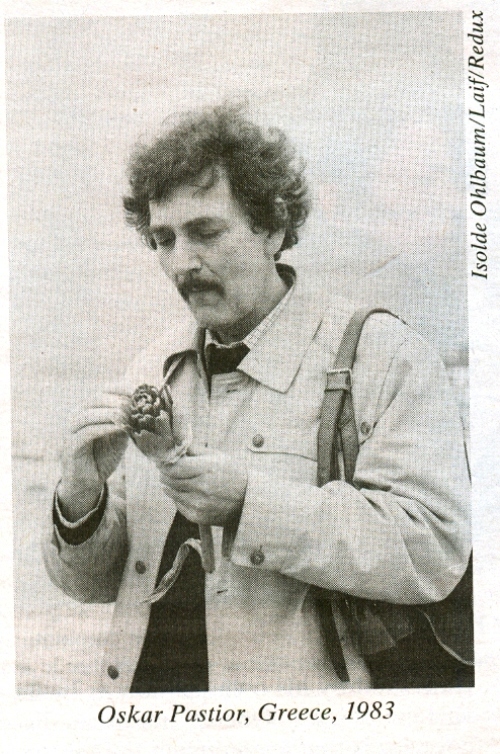

Le héros du roman, Léopold, a 17 ans et il doit partir, dans la boite d’un vieux phonographe il entasse ses biens les plus précieux: un exemplaire de Faust, un de Zarathoustra et une anthologie poétique. Bien sûr il emporte aussi des vêtements chauds car il sait qu’il part pour le nord, la Russie, pour un pays de neige. C’est avec de courts chapîtres qu’Herta Müller nous fait entendre la voix de Léopold. La vie quotidienne prend forme à travers des mots simples, des mots de tous les jours. Des mots pour dire le froid «Car dès la fin du mois d’octobre, il grêla des clous de glace», les appels interminables dans la neige, les poux, les vols, les dénonciations, l’horreur de voir Irma Pfeiffer engloutie par le mortier dans lequel elle s’est jetée par désespoir, ce désespoir qui fait dire à Léopold qu’il y a une loi qui «vous interdit de pleurer quand on a trop de raisons de le faire. Je me persuadais que les larmes étaient dues au froid, et je me crus.» Par dessus tout c’est la faim qui accompagne les prisonniers au long de ces 5 années, l’ange de la faim «qui vous dévore le cerveau» qui vous poursuit jour et nuit, qui vous fait manger votre salive, du sable. «En guise de cerveau, on n’a plus dans la tête que l’écho de la faim» et longtemps après on y pense encore «Aujourd'hui encore, je dois montrer à cette faim que j’y ai échappé. C’est tout bonnement la vie que je mange, depuis que je n’ai plus le ventre creux.» Des phrases puissantes, dures, vibrantes, pour nous transmettre la fatigue, l'épuisement «Quand la chair à disparu, porter ses os devient un fardeau qui enfonce dans le sol». La folie qui s’empare de chacun: Mitzi la sourde, Karli, le terrible Tur, Katie le planton, Fenia. Tenir, un jour encore, avec dans l’oreille la voix de sa grand-mère qui lui a dit en partant «Je sais que tu reviendras». Les années passent et le retour lui-même est souffrance, on retourne au camp encore et encore, par la pensée, par le rêve et néanmoins vivre est un devoir parce que toutes ces années Léopold a lutté contre la mort «Je n’ai jamais été aussi résolument contre la mort que durant ces cinq années de camp. Pour être contre la mort on n’a pas besoin d’avoir une vie à soi, il suffit d’en avoir une qui ne soit pas tout à fait terminée» Il reste alors à Léopold l’écriture, les mots car dit-il «Il y a des mots qui font de moi ce qu’ils veulent.» et un jour il achète un cahier. Un livre bouleversant, une œuvre forte, des images porteuses de symboles. Le récit d’Herta Müller allie réalisme et onirisme, les objets du quotidien sont personnifiés, les détails crus se mêlent aux images poétiques. Les mots sont détournés pour permettre à la souffrance de s’exprimer. Et c’est cette alliance et ce contraste qui donnent force à ce roman. Une grande œuvre. Dans la postface Herta Müller explique la genèse de son roman, sa famille victime de la déportation, le projet qu’elle a partagé avec le poète Oskar Pastior d’écrire l’expérience de celui-ci. La disparition de Pastior la contraint à s’emparer de ce récit et d’en faire ce roman tout à fait exceptionnel. Faites

une place à ce livre dans votre

bibliothèque! (1)

Chấm dứt cuộc chiến, ở Âu Châu, tù nhân về nhà, gia đình đoàn tụ, nhưng ở Lỗ Mã Ni thì không phải như thế. Tụi Nga ra lệnh, tất cả những công dân Lỗ gốc Đức sống ở Transylvanie, phải bị bắt. Có một số làm cớm cho Đức, nhưng tất cả đàn ông đàn bà, từ 17 tới 45, cớm hay không cớm, thì đều bị tống xuất. La Bascule

du souffle, de Herta Müller

Le Magazine Littéraire Review  Hơi thở đảo

điên Gác lại một

bên ánh hào quang Nobel để đọc Herta Müller, tôi chọn quyển tiểu thuyết

vừa xuất

bản và hoàn toàn bị chinh phục bởi quyển tiểu thuyết này. Dominique They Ate

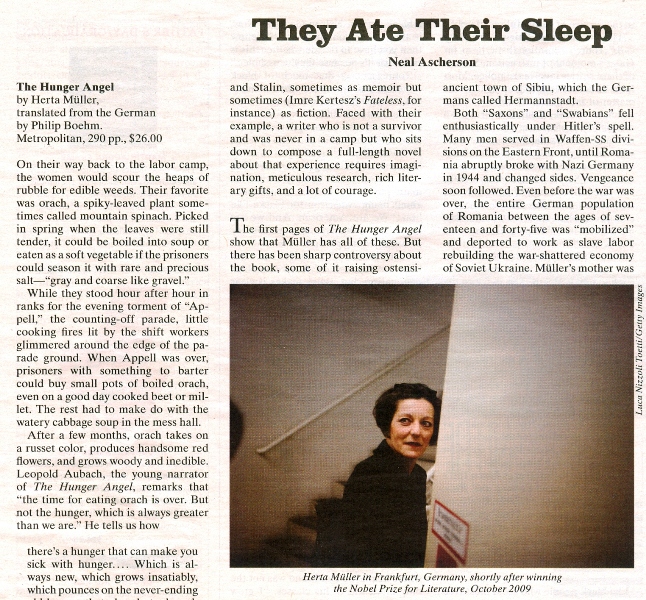

Their Sleep Neal

Ascherson The Hunger Angel by Herta

Muller, translated

from the German by Philip

Boehm. Metropolitan,

290 pp., $26.00 On their way

back to the labor camp, the women would scour the heaps of rubble for

edible

weeds. Their favorite was orach, a spiky-leaved plant sometimes called

mountain

spinach. Picked in spring when the leaves were still tender, it could

be boiled

into soup or eaten as a soft vegetable if the prisoners could season it

with

rare and precious salt-"gray and coarse like gravel." While

they

stood hour after hour in ranks for the evening torment of "Appell,"

the counting-off parade, little cooking fires lit by the shift workers

glimmered around the edge of the parade ground. When Appell was over,

prisoners

with something to barter could buy small pots of boiled orach, even on

a good

day cooked beet or millet. The rest had to make do with the watery

cabbage soup

in the mess hall. After a

few

months, orach takes on a russet color, produces handsome red flowers,

and grows

woody and inedible. Leopold Aubach, the young narrator of The Hunger

Angel,

remarks that "the time for eating orach is over. But not the hunger,

which

is always greater than we are." He tells us how there's a hunger that can

make you sick with hunger .... Which is always new, which grows

insatiably, which

pounces on the never-ending old hunger that already took such effort to

tame

.... Your mouth begins to expand, its roof rises to the top of your

skull, all

senses alert for food. When you can no longer bear the hunger, your

whole head

is racked with pain, as though the pelt from a freshly skinned hare

were being

stretched out to dry inside. Your cheeks wither and get covered with

pale fur.

... The red flower clusters were jeweled ornaments around the neck of

the

hunger angel. Leopold will

spend five years in the domain of the hunger angel, and of the hunger

angels

settled in the bodies and souls of each fellow inmate in this corner of

Stalin's Gulag. Sixty years later, as an old man looking back on his

past

before, during, and after the camp, he recognizes that his angel did

not desert

him when he was eventually released and returned to his Romanian home.

Instead,

it changed functions to become a "disabler," a bleak possessing

spirit that for the rest of his life has denied him the capacity to

show his

feelings. Herta

Muller, Nobel laureate, is a writer who releases great emotional power

through

a highly sophisticated, image-studded, and often expressionist prose.

It must

have been a combination of her own

technical self-confidence and the urge to break silence about the fate

of her

parents' generation that led her to attack a project as difficult as

this.

Celebrated survivors from Primo Levi to Varlam Shalamov have written

unforgettable books about life and death in the camp empires of Hitler

and

Stalin, sometimes as memoir but sometimes (Imre Kertesz's Fateless, for

instance) as fiction. Faced with their example, a writer who is not a

survivor

and was never in a camp but who sits down to compose a full-length

novel about

that experience requires imagination, meticulous research, rich

literary gifts,

and a lot of courage. *

The first

pages of The Hunger Angel

show that Muller has all of these. But there has been

sharp controversy about the book, some of it raising ostensibly

literary

objections but some that are indirectly ethical or political and

some-fumes

from certain Romanian gutters-simply slanderous. The narrative of the

novel is

about the miseries and rare epiphanies of the Gulag as they have an

impact,

physically and imaginatively, on a young boy; the political background

of it

all is confined to allusions. But it's unfair to any reader not to know

something about where Muller-and her story are coming from. In

pre-1939

Romania, within its unstable frontiers, there lived two large

German-speaking

minorities. One was the mainly Protestant "Saxon" population in the

hills of Transylvania. The other group, the "Banat Swabians," lived

in the plains toward Hungary and were mostly Catholic.* Herta Muller

grew up in

a Swabian village, and most of her fiction-like her brave struggles

against the

Communist police state- has been concerned with the experience of the

Banat

Germans. This time, however, her novel's protagonist Leopold comes from

the

other community, from a Transylvanian family in the ancient town of

Sibiu,

which the Germans called Hermannstadt. Both

"Saxons" and "Swabians" fell enthusiastically under

Hitler's spell. Many men served in Waffen-SS divisions on the Eastern

Front,

until Romania abruptly broke with Nazi Germany in 1944 and changed

sides.

Vengeance soon followed. Even before the war was over, the entire

German

population of Romania between the ages of seventeen and forty-five was

"mobilized" and deported to work as slave labor rebuilding the

war-shattered economy of Soviet Ukraine. Muller's mother was among

them. When

their exile ended five years later, some 15 percent had died of

exhaustion,

hunger, and disease. That

setting

gave a special edge of bitterness and loneliness to the suffering of

that

generation. Even after they were allowed to return to Romania, several

thick

layers of silence still covered what had happened to them. The postwar

Communist regime treated the German minority as potential "fascist

saboteurs"; later, the ultra-nationalist tyranny of Nicolae Ceausescu,

constructing its own "Dacian-Thracian" myth of origin, persecuted

them as racial aliens. To publicly describe their deportation would

have been

taken not only as "anti-Soviet propaganda" but also as an un-welcome

reminder of Romania's own fascist period under the pro-Nazi

dictatorship

(1940-1944) of Ion Antonescu. So this

segment of the past was blanked out. Herta Muller, born in 1953, grew

up in a

society where the fate of her parents' generation was mentioned only

within the

family, and then as seldom as possible. the private dream was to reach

Germany-the non-Communist West Germany. But the frontiers were tightly

closed;

alone among Central and East European states in the immediate aftermath

of war,

Romania did not expel its German minorities. As Muller has recorded in

two

devastating earlier novels (The Appointment and The Land of Green

Plums), the

only escape routes were either to risk death under the bullets of

frontier

guards or to earn a passport by becoming an informer for the Securitate

secret

police. Only when the borders began to ease open, in the late 1980s and

then

after the bloody over throw of Ceausescu's tyranny, did mass emigration

to

Germany and Austria begin. Of the 115,000 "Saxons" still in

Transylvania in 1989, some 90,000 had left by 1992. *

The Hunger

Angel is an album of brief or sometimes longer sketches. Each is

a literary

work complete in itself, but the sketches are set more or less

chronologically.

They begin in the train of cattle cars that drags its victims over many

days

and nights deeper and deeper into the Soviet Union, and end with the

released

but psychically "disabled" Leopold confronting the house and family

that is supposed to be his home. As the scenes follow one another, a

cast of

characters emerges. The camp commandant is a bawling Russian brute of

no

significance; real authority rests with the "kapo," Tur Prikulitsch,

a prisoner rewarded with almost every privilege. "He doesn't know the

hunger angel." Muller's description of him is a good example of her

rather

Kafkaesque prose, her cunning use of simile and metaphor that here

inverts the

animate and the inanimate: He has the whole

day to admire himself .... He's athletically built, with brass-colored

eyes and

an oily gaze, small ears that lie flat like two brooches, a porcelain

chin,

nostrils pink like tobacco flowers, a neck like candle wax. At

another

level, this passage subtly reminds the reader that Leo is gay. Still a

teenager, he was deported just at the moment when he was embarking on

deliciously perilous cruising in the local park at home. But in the

camp

homosexuality would mean death. The only tolerated form of sex takes

place in

an abandoned drainpipe between women deportees and German prisoners of

war,

until both parties become too starved and cold to bother. Leopold

draws close to Bea Zakel, the prisoner-mistress of the kapo who

uneasily shares

the kapo's privileges: "she wants to live like him but still be one of

us." Hunger--the struggle not to die-is the scale on which everything

is

weighed, in a place where Leopold creeps by night to the garbage heap

to wolf

down frozen potato peelings, and even Tur Prikulitsch is somehow aware

that in

a bunger-world there are debts that he must pay. So when Bea Zakel

takes

Leopold's treasured silk scarf and, instead of trading it for food,

gives it to

her lover, the kapo discreetly arranges that Leopold will be left alone

in front

of a mound of potatoes. (He manages to stuff nearly three hundred of

them into

his clothing; back in his barrack hut, he puts some aside for himself

but uses

the rest to payoff borrowed salt or sugar.) Other

memorable figures include Kati, a tiny half-witted woman who does not

even

understand that she is in a camp, Leo's friend Trudi from Hermannstadt

who is

assigned to stacking frozen corpses after her foot is mangled by a

wagon

carrying rubble, and the Gasts. Frau Heidrun Gast is clearly dying;

"she already

had the dead-monkey face, the slit mouth running from one ear to the

other,

swollen eyes and the white hare in the hollows of her cheeks." (The

white

hare belongs to one of Muller's typically involuted wordplays. One of

the

varieties of coal the prisoners have to shovel is "gas coal"-gazovy,

which in Ukrainian becomes hazoviy; this sounds to Muller like the

words

Hase-vey (hare woe), which in turn become a term running through the

novel as a

synonym for death.) When Frau Gast becomes too weak to eat, her husband

can't

help thrusting his spoon into her bowl and .. stealing her cabbage

soup. And

Leo puts his spoon in too. How could he not? "That was the way of the

world: because each person couldn't help it, no one could." *

And yet

shafts of light break into this horrible landscape. Leo holds tightly

to his

grandmother's words as he left the house: "I know you'll come back." He

is

reminded of them when he and a workmate are dosed with milk as a lung

remedy

for boiler fumes: To help us

last longer, once a month at the factory guard shack they pour half a

liter of

healthy milk into a tin bowl. It's a gift from another world. It tastes

like

the person you could have remained if you hadn't gone into the service

of the

hunger angel. I believe the milk. And the milk

in turn reminds him of a different moment of humanity, another "gift

from

another world." Begging for food around village doors, he is taken in

by a

Russian woman whose own son, denounced for some remark by a neighbor,

has been

sent to a penal battalion. She gives him a bowl of wonderful soup and

then,

seeing his nose dripping, pushes into his hand a snow- white batiste

handkerchief embroidered in tsarist times with a decorated silk border.

"I

was convinced that my grandmother's parting sentence ... had turned

into a

handkerchief." Although he could have traded it for food, Leopold hides

and treasures it: "I'm not ashamed to say that the handkerchief was the

only person who looked after me in the camp."

Dexterous

with imagery and wordplay, Herta Muller is also amazingly at home with

the

nature of material things. The Hunger Angel is full of confident

descriptions

of the stuff the prisoners are working with, and of what it feels like

to

shovel, scrape, or carry it. She knows the foulness of hefting leaky

cement

bags in wet weather, the delight of acquiring almost balletic

proficiency at

wielding a heavy "heart-shovel" of coal, the taxonomy of different

kinds of boiler slag that each require different skills to remove them,

the

polychrome layers in a sand quarry, the nightmare of carrying a

ten-kilo,

freshly pressed, and still unstable cinder block from its pressing

frame to the

drying area without letting it collapse: In the

evening a spotlight cast a beam of harsh light on the scene. Moths

twirled around,

and the mixing drum and the press loomed in the light like machines

covered

with fur. The moths weren't drawn only to the light. The moist smell of

the mix

attracted them, like night- blooming flowers. They settled on the

blocks that

were drying .... They also

settled on the block you were carrying and distracted you from your

balancing

act. ... Occasionally two or three appeared at once and sat there as

though

they'd hatched out of the block itself. As though the wet mix on the

board were

not made of slag, cement, and lime slurry but was a square lump of

larvae from

which the moths emerged. How does she

know all this? How does she. know all the various smells encountered

across the

rusting industrial mess of the work site, and what they remind you

of-the

fire-clay crystals smelling like chrysanthemum bushes, the tank water

like

naphthalene mothballs, the rotting asphalt like shoe polish, the

abandoned and

solidified chemical fertilizer like alum? In the

novel, those comparisons are part of a technique Leo Aubach has in-

vented to

refuse "to let the chemicals have their poisonous way with me." He

reinterprets the odors as fragrances and "succeeded in creating a

pleasant

addiction for myself." In the same way, he joins the camp women in

escaping hunger by eating sumptuous imaginary meals, reciting elaborate

recipes

(hazelnut noodles, boiled pig's head with horseradish). Climbing into

their

bunks at night, they climb into their hunger and proceed to eat their

sleep,

greedy dream by dream. *

Nobody has

any idea when they will be released, if ever. By the fourth year over

three

hundred of them have died, their bodies stacked in frozen snow behind

the

sickbay until the spring thaw allows them to be dismembered and buried

in a

pit. When the only ethnic Romanian dies-a woman apparently grabbed off

the

street by the train guards in order to make up the prisoner numbers-Bea

Zakel

orders her long hair to be cut off in order to stuff a window cushion

to stop

drafts. To strip the clothes off a fresh corpse, or to share out his or

her

little hoard of bread fragments-that is normal. "When all you are is

skin

and bones, feelings are a brave thing." But Bea Zakel has crossed the

line

of what is tolerable. A

little

later, Leo receives a postcard, his first message from home in the

years since

he entered the camp. It consists of

the photograph of a baby, sewn to the card; underneath in his mother's

hand is

written: "Robert b. April 17 1947." Not a word for Leo, who concludes

that his parents have had another baby because they have given up on

him. His

mother might as well have written: "As far as I'm concerned, you can

die

where you are, we'll have more room at home." He

forces

himself not to answer the card or make any effort to contact his

family. More

and more, he feels that the camp, or rather existence in the camp, has

become

his only real home: Some people

speak and sing and walk and sit and sleep and silence their

homesickness, for a

long time and to no avail. Some say that over time homesickness loses

its

specific content, that it starts to smolder and only then becomes

all-consuming, because it's no longer focused on a concrete home. I am

one of

the people who say that. Even the

hideous figure of Fenya, the Russian woman who holds the power of life

and

death each morning as she weighs out the miserable bread ration,

trimming each

piece with her huge knife, comes to seem majestic rather than hateful.

"Fenya seemed to exude a Communist saintliness." She is just.

"She gives me my share of food .... I have the camp, and the camp has

me.

All I need is a bunk and Fenya's bread and my tin bowl. I don't even

need Leo

Auberg." When he

is

released, into the bleak Stalinist landscape of Romania in 1950, it is

not only

fear of political consequences that makes Leo keep his memories to

himself.

It's a sort of shame, which he knows will be shared and understood by

other

survivors. He thinks he spies Bea Zakel in a window, her blond braid

turned

gray, but walks on without

making a sign to her. In the main square of Hermannstadt, he meets his

camp

friend Trudi limping toward him. She drops her cane on the ground and

bends

down as if to lace up her shoe: For our own

sakes we preferred to act as though we didn't know each other. There's

nothing

to understand about that. I quickly turned my head, but how gladly I

would have

put my arms around her and let her know that I agreed with her. A

letter

comes from another camp comrade in Vienna; Tur Prikulitsch has been

found dead

under a Danube bridge, his skull split by an axe. Leo buys some lined

notebooks

and begins to write. At first he tries to tell the truth. But as time

passes he

tears up the passages recording those shafts of light-the milk, the

batiste

handkerchief-and instead writes a story of how he triumphed over

starvation by

his own ingenuity and self-discipline: When I got

to the hunger angel I went into raptures, as if he'd only saved me and

not

tormented me .... *

The Hunger

Angel is a wonderful, passionate, poetic work of literature,

written-as one

entre put it, in the blood of Herta Muller's own heart. The

novel

wasn't welcomed every-where, when it appeared in its original German in

2009.

The basest criticism of all came from some of Muller's fellow

Romanian-German

exiles, egged on by the numerous veterans of the old Securitate who are

still

all too active. Having

failed to blackmail her into becoming an informer, they took revenge by

spreading the false rumor that she had agreed to inform as the price of

getting

out of Romania in the 1980s. The exiles also took the view that Muller

had

treacherously “befouled her nest" by recalling the Nazi past of the

previous generation. This

rubbish

was predictable and worthless. More surprising and much more

interesting was a

harsh and elaborate attack in the liberal-intellectual German weekly

Die Zeit

by the critic Iris Radisch. She denounced The Hunger Angel on two

distinct

grounds: that it was written in an affected and inappropriate style,

and that

what Radisch referred to as "Gulag literature" should not be

attempted "at second hand," by somebody who had never experienced the

camp. Before

considering Radisch's comments, a foreigner ought to remember that

German

literary criticism has a tradition of theatrical, annihilating

ferocity. The

writings of the powerful German critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki, himself a

refugee

from Poland, are a case in point. Some of his reviews of the later

fiction of

Gunter Grass seemed to leave only a blackened crater where once there

was a

novel. Iris Radisch dismisses The Hunger Angel as "powdered and stagey

...

a childish-magical tenderness nestles around the horror as a foot-wrap

nestles

itself around a prisoner's foot, and veils everything and everyone in

the

gruesomely prettified melancholy of a woebegone lullaby." She

particularly objects to Muller's old-fashioned Expressionist reliance

on

metaphor and simile, and to her lyrical vocabulary that ornaments the

grimmest

experiences. The result is "an artificial-snow prose that buries pain

under an antiquarian pathos." This

seems

an eccentric complaint. Herta Muller's imagery is often complex and

obscure,

more so than in her previous novels set in the Romania of the Ceausescu

dictatorship, but never sentimental. Radisch contrasts this book with

the

spare, metaphor-free style of Imre Kertesz, who turned his time in

Buchenwald

into fiction. But there are many ways to write a good novel. Projecting

bizarre

fantasies and surreal, anthropomorphic scenery into a Soviet labor camp

might

not have worked with a lesser artist than Muller, but there's never a

moment in The Hunger Angel in

which a reader will lose confidence in her command of

language. Mention

of

Kertesz brings up the other point: Radisch's strange objection to

"secondhand" writing about the twentieth century's prison camps and

genocides. She declares that "the era of Gulag literature, which took

our

breath away, has come to its natural end, and can't be revived as a

second-hand

industry by harp-twanging and angelic choirs." But the Polish writer

Eva

Hoffman dealt with this problem in her remarkable book After Such

Knowledge

(2004). There she asked for recognition for the "second generation"

of survivors. Those who did not directly can't be revived as a

second-hand

industry by harp-twanging and angelic choirs." But the Polish writer

Eva

Hoffman dealt with this problem in her remarkable book After Such

Knowledge

(2004). There she asked for recognition for the "second generation"

of survivors. Those who did not directly suffer the Gulag or the

Holocaust, she

wrote, have grown up to be an organic part of that experience through

their

bond with their parents. "The second generation is the hinge generation

in

which received; transferred knowledge of events is transmuted into

history, or

into myth." Or in the case of Herta Muller, precisely of that hinge

generation, into superb imaginative fiction. + NYRB May 24,2012 |