THE PROPHET

OF DECLINE

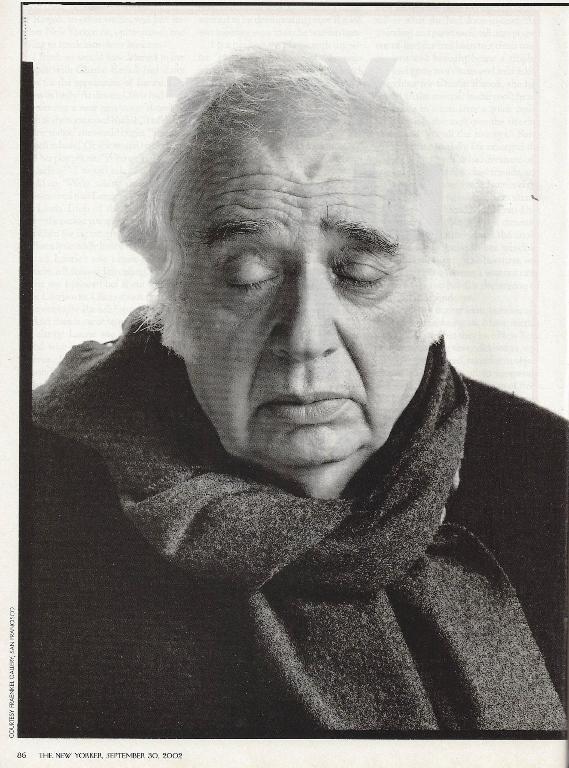

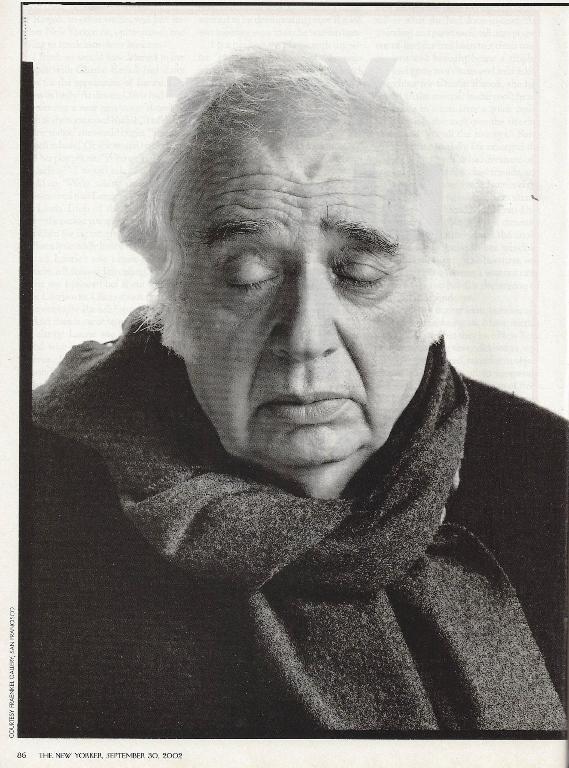

PHOTOGRAPH

BY RICHARD AVEDON

Harold

Bloom, October 28, 2001, New York City.

PROFILES

THE PROPHET

OF DECLINE

Harold

Bloom's influential anxieties.

BY LARISSA

MACFARQUHAR

Harold Bloom, nhà tiên tri

của thoái trào.

Có 1

thời,

xa xưa lắm rồi, khi Gấu chưa từng đọc Thầy Cuốc, lâu lâu… loáng thoáng

thấy, Thầy

hay nhắc đến Harold Bloom.

Giờ thì hết

rồi.

Và Gấu cứ

nghĩ Bloom là Thầy của Thầy Cuốc, như Roland Barthes vân vân và vân vân.

Đếch phải!

Tình cờ vớ

được bài này trong 1 số báo cũ, The New

Yorker, Sept 30, 2002

TV post và dịch,

nếu có thể, để trình ra 1 nhà phê bình đương thời của mũi lõ, xem có

giống những

nhà phê bình Mít mũi tẹt tí nào chăng?

Hà, hà!

THE PROPHET

OF DECLINE

It is

tempting to say that Harold Bloom is a man marooned in the wrong place

and

time, and that living out his late years in twenty-first-century

America is what's

making him miserable. It is so easy, after all, to imagine him

gleefully

roistering through taverns like his Shakespearean hero, Falstaff,

constructing

a tottering folly of puns; or denouncing Aristotelian aesthetics at

some

bacchanal in Rome (although the thought of Bloom in tights or' a toga

is

alarming). One can picture him a- feverish poet in nineteenth-century

Russia,

growing dotty and millennial like the elder Tolstoy. "He's a wandering

Jewish scholar from the first century," Sir Frank Kermode, the English

literary critic, says.

"There's

always a pack of people sitting around him to see if any bread or

fishes are

going to be handed out. And I think there is in him a lurking sense

that when

the true messiah comes he will be very like Harold." But to think this

way

is to make two mistakes. One is to suppose that mere history-a change

of

scene-can alter a spirit. That is a very un-Bloomian notion. And the

second is

to believe that miserable is a bad thing to be. Bloom, in his lyric

sadness,

his grandiloquent fatigue, and his messianic loneliness, is a great

soul.

"He did not seem happy,” a former student says. "But happiness seemed

a trivial quality compared to whatever Harold was." Bloom is not low so

much as over the top. In his misery, he is magnificent.

Bloom is a

prophet of decline. In his view, Western literature reached its apogee

in

Shakespeare, and it has been downhill ever since. Bloom loves Emerson

and

Whitman but he doesn't believe them: to him, belatedness is now a

permanent

condition of man, and there can be no overcoming it-no return, even in

America,

to an original fullness or freshness or purity of spirit. But it would

not be

right to say that Bloom is nostalgic for the past. Unlike the cultural

conservatives with whom he is often (wrongly) grouped, he does not long

for a

more genteel or simpler era. In his view, the fact that Shakespeare

lived in

sixteenth-century England does no credit to the time or the place,

because

Shakespeare's genius was sui generis-it emerged out of no-where. The

truth is,

Bloom has no interest in history as such-no interest, that is, in the

difference between one time and another-because to him all poetry that

is

valuable is timeless. Anything that time has made foreign is a period

piece,

bric-a-brac.

In fact,

it's not just historicizing that Bloom rejects-it's pastness per se. He

reads

poems as though reliving their creation. Bloom likes his poems bloody,

trailing

ruptured veins and muscles torn in struggle. It is the lyric urge and

the

strife of poetic parturition that he values, more than the poem itself

For the

epigraph of his book "Shakespeare," Bloom chose a quotation from

Nietzsche's "Twilight of the Idols" that is an extraordinary

statement to place at the beginning of a book about Shakespeare, or,

indeed,

about any sort of literature: "That for which we find words is

something

already dead in our hearts. There is always a kind of contempt in the

act of

speaking."

Bloom is a

literary critic at Yale and New York University, an authority on the

Romantic poets

and on Yeats and Wallace Stevens. He is the author of "The Anxiety of

Influence" and, more recently, of best-selling books such as "The

Western Canon," "The Book of J," and "How to Read and

Why." Next month, he publishes his twenty-eighth book, eight hundred

pages

long, titled "Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Minds."

Despite these critical credentials, however, Bloom is not, for the most

part, a

close reader. He doesn't dissect stanzas, he doesn't worry words,

because he

doesn't read the way most people do. Bloom is famous for his memory and

his

reading speed. He has memorized a large proportion of canonical poetry

written

in English; once, when drunk, as an undergraduate at Cornell, he

recited Hart

Crane's long poem "The Bridge" backward, word by word. He claims that

in his youth he read a thousand pages an hour. Bloom has had poems

inside him

for so long that he doesn't really read them anymore. They are not a

series of

lines following one after the other--they exist in him all at once. He

has

swallowed them whole.

***

Bloom,

sitting, temporarily unattended, somewhere unfamiliar. He sits with his

arms

hugged around himself, head sunk, blinking miserably, in the posture of

one who

is obliged to wait in the rain without an umbrella or hope of shelter.

From

time to time, he hunches his shoulders and twists with a pained

expression, as

though trying to shift something heavy on his back.

Bloom's face

is a cluster of big, swollen, sensing instruments: a heroic nose,

nostrils

dilating; plump, colossal lips; a giant's heavy eyes, rolling or

tearing; thick,

congested eyebrows, heaving up or thrusting down; deep fissures in the

forehead.

There is no mere skin on his face-it is all membrane. Bloom is an

intensely

sensitive animal, vulnerable to the most delicate waft of emotion. His

stomach

is prodigious, like a great cathedral, in which all the uncountable

poems and

plays that he has swallowed roil and commingle with his own passions.

Bloom has

suffered heart attacks and stomach ulcers and is intermittently, and

with tepid

conviction, on a diet. But his Falstaffian fat is part of his majesty.

When

Bloom teaches, he uncoils and grows even larger. He seems to his

students not

quite in control of himself: he gets carried away, he throws himself

around, he

slips his hand inside his shirt and grasps his chest, he quivers with

feeling.

He is a superb spectacle. He worships, he adores, he falls at a poet's

feet,

but not deferentially-intimately. He

is-rabbinical, prophetic; but he is also, in his bigness and his

emotion, like

a giant mother. He is disarmingly feminine: his voice, emerging out of

the roomy

torso, is a gentle tenor. A number of his female students find the

combination

of these qualities overwhelmingly, destructively, seductive.

Some of

Bloom's students form a kind of Orphic cult about him'. They become

preoccupied

with him, and spend hours engaged in awed or prurient speculation.

Absurd

rumors circulate. It is whispered that, using his astonishing memory,

he worked

as a document courier, in the nineteen-fifties, for the Israeli

government. A

small scar on his forehead is suspected to be the mark of a bullet

wound he

suffered in Palestine in the 1948 war, He was said to be the

best-selling

romance author Harold Robbins, writing under a pseudonym.

Women

students go early to class in order to secure a seat next to him. "I

suppose

he was already on his way to Wordsworth's egotistical sublime," one

former

student says. "There was always something exciting about the way he

staged

that sense that he had some enormous thing inside him, some huge soul

or being

that's too big for this world and his body. But his teaching seemed

crushing to

me. You weren't encouraged to think on your own. He was the sow who

rolls over

and kills her young." "I really feel I am a different person for having

studied with Bloom," another student says. "He changed the scale of

my ambition: he showed me that there was a moral righteousness in

reading. He made

me feel it." "I had the

most intense castration dream of my life after one of his classes,"

says a

third, a woman. "I dreamed that I had a dotted line for cutting drawn

across my neck."

Many of

Bloom's students love him; others grow up to become feminists and

Marxists and

New Historicists, and reject everything he taught them. Bloom is

Falstaff; but

Falstaff was betrayed by only one Hal. Bloom is betrayed by thousands.

***

Every year,

Bloom is invited to Europe, to receive a prize, or to give a lecture,

or for

some other reason. Every year, he accepts, and then, every year at the

end of

the journey, he vows never to travel again. This year, on a radiant

afternoon

in late spring, Bloom boarded a ferry from Barcelona to Majorca.

Some months

previously, he had been approached by a man named Michaelangelo, a

Spanish

psychoanalyst who practices in London and is a passionate Borges

enthusiast.

With the aid of a wealthy local lady, Michaelangelo had established a

Majorcan

Borges society and had invited Bloom to speak at a society dinner.

Bloom had

accepted the invitation because he was planning to be in Spain anyway:

he had

been summoned to Barcelona to receive the Premi Internacional

Catalunya-the

Catalan equivalent, he was told, of the Nobel.

Upon his

arrival in Barcelona, Bloom had been reminded, earlier than usual, of

his

previous year's vow. He had discovered that his acceptance of the prize

obliged

him to submit to two and a half days of interviews, so that by the time

he

departed for the ferry he was utterly exhausted. In the car on the way

to the

dock, Bloom's wife, Jeanne, chatted with the driver about Snowflake,

the famous

albino gorilla who lives in the Barcelona zoo. Jeanne had read in the

newspaper

that specialists at the zoo had been breeding him over and over again

in the

(vain) hope that he would produce an albino heir, even though Snowflake

was now

quite elderly, and the constant fornication had left him visibly

depleted.

"Let us change the subject, please," Bloom entreated weakly from the

front seat. "I am beginning to identify with him."

The ferry

ride, at least, was something to look forward to. Bloom had been told

by an

American friend that travelling by boat between Barcelona and Majorca

was a

beautiful passage, the water as smooth as a sea of glass. Bloom had

been taken

with this phrase, "sea of glass," and during the dark days of

interviews

he had pictured himself sitting on a sunny deck, as peacefully and

solidly as

if he were seated on a stage while a