|

|

Naipaul's

Book of the World

Hilary

Mantel

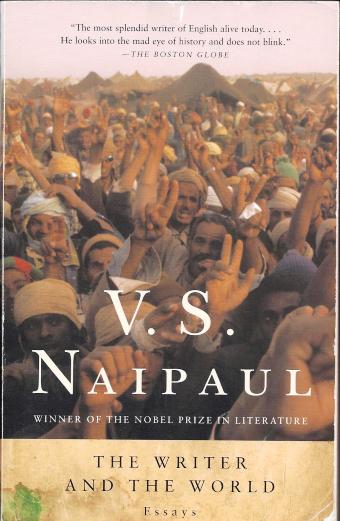

Trong cuốn

"Nhà văn và Thế giới", có bài diễn thuyết của Naipaul, Nền văn minh phổ

cập của

chúng ta, “Our Universal Civilization”, tại Học Viện Manhattan, NY. TV

sẽ giới

thiệu, vì nó liên quan tới vấn nạn khủng bố, và cùng với nó, như 1 đối

trọng, “bịnh

Tây Phương”, a “Western disease”. Ngoài ra TV sẽ giới thiệu bài Naipaul

viết về

cuốn sách thân cận với ông nhất, Ngôi nhà cho me-xừ [A House for Mr.]

Biswas. Bài

này cho Mít chúng ta thấy, có 1 cách viết khác hẳn chúng ta thường

viết, do bị ảnh

hưởng của Tẩy, belles lettres, văn là phải đẹp.

Bài trong sách, dài hơn

nhiều, so với bài trên net, và được ghi là Postscript: Our Universal Civilization.

Our

Universal Civilization

Đúng hơn, là bài này:

Our

Universal Civilization

Sir V.S.

Naipaul

On October

30, 1990, V S. Naipaul, considered by many to be the greatest living

English

language novelist, delivered the fourth annual Walter B. Wriston

lecture in

Public Policy, sponsored by the Manhattan Institute. Mr. Naipaul takes

as his

subject the “universal civilization” to which the Western values of

tolerance,

individualism, equality, and personal liberty have given birth. He

describes

the personal and philosophical turmoil of those who find themselves

torn

between their native civilizations and the valued of universal

civilization. We

are pleased to present his remarks here in full.

Diễn văn Nobel

Naipaul Page

Typical sentence

Easier to pick two of them. What’s most typical is the

way one sentence qualifies another. “The country was a tyranny. But in

those days not many people minded.” (“A Way in the World”, 1994.)

Câu văn điển hình:

Dễ kiếm hai câu, điển hình nhất, là cái cách mà câu này

nêu phẩm chất câu kia:

"Xứ sở thì là bạo chúa. Nhưng những ngày này, ít ai "ke" chuyện này!"

Naipaul rất

tởm cái gọi là quê hương là chùm kế ngọt của ông. Khi được hỏi, giá như

mà ông

không chạy trốn được quê hương [Trinidad] của mình, thì sao, ông phán,

chắc nịch,

thì tao tự tử chứ sao nữa! (1)

Tuyệt.

(1)

INTERVIEWER

Do you ever wonder what

would have become of you if you had stayed in Trinidad?

NAIPAUL

I would have killed

myself. A friend of mine did-out of stress, I think. He was a boy of

mixed race. A lovely boy, and very bright. It was a great waste.

Sir V.S.

Naipaul (1932- ): Nobel văn chương 2001

“Con người

và nhà văn là một. Đây là phát giác lớn lao nhất của nhà văn. Phải mất

thời

gian – và biết bao là chữ viết! – mới nhập một được như vậy.”

(Man and writer were the same

person. But that

is a writer’s greatest discovery. It took time – and how much writing!

– to arrive

at that synthesis)

V.S. Naipaul, “The Enigma of

Arrival”

Trong bài tiểu luận “Lời

mở đầu cho một Tự thuật”

(“Prologue to an Autobiography”), V.S. Naipaul kể về những di dân Ấn độ

ở

Trinidad. Do muốn thoát ra khỏi vùng Bắc Ấn nghèo xơ nghèo xác của thế

kỷ 19, họ

“đăng ký” làm công nhân xuất khẩu, tới một thuộc địa khác của Anh quốc

là

Trinidad. Rất nhiều người bị quyến rũ bởi những lời hứa hẹn, về một

miếng đất cắm

dùi sau khi hết hợp đồng, hay một chuyến trở về quê hương miễn phí, để

xum họp

với gia đình. Nhưng đã ra đi thì khó mà trở lại. Và Trinidad tràn ngập

những di

dân Ấn, không nhà cửa, không mảy may hy vọng trở về.

Vào năm

1931, con tầu SS Ganges đã đưa một ngàn di dân về Ấn. Năm sau, trở lại

Trinidad, nó chỉ kiếm được một ngàn, trong số hàng ngàn con người không

nhà nói

trên. Ngỡ ngàng hơn, khi con tầu tới cảng Calcutta, bến tầu tràn ngập

những con

người qui cố hương chuyến đầu: họ muốn trở lại Trinidad, bởi vì bất cứ

thứ gì họ

nhìn thấy ở quê nhà, dù một tí một tẹo, đều chứng tỏ một điều: đây

không phải

thực mà là mộng.

Ác mộng.

“Em ra đi

nơi này vẫn thế”. Ngày nay, du khách ghé thăm Bắc Ấn, nơi những di dân

đợt đầu

tiên tới Trinidad để lại sau họ, nó chẳng khác gì ngày xa xưa, nghĩa là

vẫn

nghèo nàn xơ xác, vẫn những con đường đầy bụi, những túp lều tranh vách

đất, lụp

xụp, những đứa trẻ rách rưới, ngoài cánh đồng cũng vẫn cảnh người cày

thay

trâu… Từ vùng đất đó, ông nội của Naipaul đã được mang tới Trinidad,

khi còn là

một đứa bé, vào năm 1880. Tại đây, những di dân người Ấn túm tụm với

nhau, tạo

thành một cộng đồng khốn khó. Vào năm 1906, Seepersad, cha của Naipaul,

và bà mẹ,

sau khi đã hoàn tất thủ tục hồi hương, đúng lúc tính bước chân xuống

tầu, cậu

bé Seepersad bỗng hoảng sợ mất vía, trốn vào một xó cầu tiêu công cộng,

len lén

nhìn ra biển, cho tới khi bà mẹ thay đổi quyết định.

Duyên Văn

1 2

Chính là nỗi đau

nhức trí thức thuộc địa, chính nỗi chết không rời đó, tẩm thấm mãi vào

mình, khiến cho Naipaul có được sự can đảm để làm một điều thật là giản

dị: “Tôi gọi tên em cho đỡ nhớ”.

Em ở đây, là đường

phố Port of Spain, thủ phủ

Trinidad. Khó khăn, ngại ngùng, và

bực bội – dám nhắc đến tên em – mãi sau này, sau sáu năm chẳng có chút

kết quả ở Anh Quốc, vẫn đọng ở nơi ông, ngay cả khi Naipaul bắt đầu tìm

cách cho mình thoát ra khỏi truyền thống chính quốc Âu Châu, và tìm

được can đảm để viết về Port of Spain như ông biết về nó. Phố Miguel (1959), cuốn sách đầu

tiên của ông được xuất bản, là từ quãng đời trẻ con của ông ở Port of

Spain, nhưng ở trong đó, ông đơn giản và bỏ qua rất nhiều kinh nghiệm.

Hồi ức của những nhân vật tới “từ một thời nhức nhối. Nhưng không phải

như là tôi đã nhớ. Những hoàn cảnh của gia đình tôi quá hỗn độn; tôi tự

nhủ, tốt hơn hết, đừng ngoáy sâu vào đó."

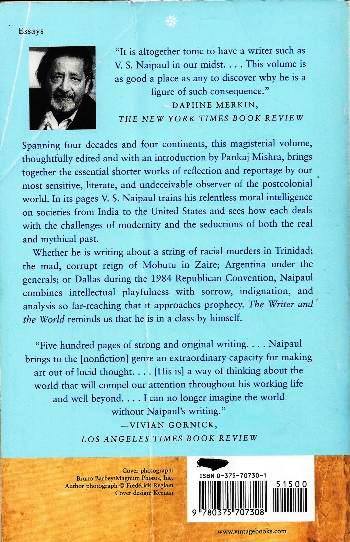

In this third instalment of our series on what makes distinctive writers

distinctive, Robert Butler tackles V.S. Naipaul on the eve of his 31st

book

From INTELLIGENT LIFE Magazine, Autumn 2010

V.S. Naipaul was born in Trinidad in 1932, when literacy

among Indian men on the island stood at 23%. Naipaul’s father had

taught himself to read and write and became a journalist for the Trinidad

Guardian. He gave his son the idea of the writer’s life and the

idea that it was a noble calling. The young Vidia slept on the

verandah, where the varied life of Port of Spain, captured in his first

book “Miguel Street” (1959), “unrolled every day in front of my eyes”.

The conditions that made his literary ambitions so raw and improbable

also gave Naipaul his unique perspective. His early exposure to

Trinidad’s diverse population—Africans, East Indians, Venezuelans,

Chinese, Portuguese, Americans, Syrians and Lebanese—ensured that he

wouldn’t sentimentalise other cultures. This gift was immeasurably

deepened by his travels in South America, Africa, India, Pakistan, Iran

and South-East Asia.

Naipaul attaches equal value to his fiction and

non-fiction and has mastered (as the Nobel committee said) a form of

writing that combines the two. His 31st and latest book, “The Masque of

Africa” (out now in Britain, and in October in America), sees this

tireless observer return, albeit in a slightly more leisurely style

(“we went in his ambassador’s car”), to a continent he first visited 44

years ago.

Golden rule

After university, Naipaul decided the way he had written

undergraduate essays was not “proper writing”. He set himself the task

of learning to write all over again, this time using only simple direct

statements. “Almost writing ‘the cat sat on the mat’. I almost began

like that.” For three years he stayed with those rules. He recently

provided a list of seven rules for beginners at the request of an

Indian newspaper: (1) write sentences of no more than ten to 12 words;

(2) make each sentence a clear statement (a series of clear linked

statements makes a paragraph); (3) use short words—average no more than

five letters; (4) never use a word you don’t know the meaning of; (5)

avoid adjectives except for ones of colour, size and number; (6) use

concrete words, avoid abstract ones; (7) practise these rules every day

for six months.

Key decision

To discard the metropolitan notion of the writer that he

had grown up with—a Somerset Maugham or Evelyn Waugh who moves from a

place of civilised security to investigate the world beyond his own

shores. That kind of “I” was not available to Naipaul. “My subject was

not my sensibility, my inward development, but the worlds I contained

within myself.” (“The Enigma of Arrival”, 1987.)

Strong point

Something he admires in other writers: “Kipling looked

hard at a real town.”

Favourite trick

In his later work, he repeats a phrase from one

paragraph in the next one, which gives his prose an almost biblical

sense of progress. The mythic tone is heightened by short words and

inverted sentences: “In the morning there came the fighter plane.” (“A

Bend in the River”, 1979.) Every evening Naipaul reads out loud what he

has written during the day. Or used to—nowadays he has what he has

written read out to him. This lifelong habit gives his prose the

weightiness of considered thought and the lightness of conversation.

Role models

His father—“possibly the first writer of the Indian

diaspora”—for his short stories about Trinidad’s Indians. Joseph

Conrad, for seriousness and a sense of those living on “the other side

of the fence”. Flaubert, for the “selection and achievement of

detail”. Shakespeare, for freshness of language and the power of his

simplest lines.

Typical sentence

Easier to pick two of them. What’s most typical is the

way one sentence qualifies another. “The country was a tyranny. But in

those days not many people minded.” (“A Way in the World”, 1994.)

"The Masque of Africa"

was published by Picador on August 31st, and by Knopf in America on

October 19th

|

|