|

Bản dịch tiếng Anh mới nhất IN FRONT OF

THE LAW IN FRONT OF

the Law stands a doorman. A man from the country comes to this doorman

and asks

to be admitted to the Law, but the doorman says that he can't allow him

to

enter. The man reflects on this and then asks if he can assume that

he'll be

allowed to enter later. "It's possible," says the doorman, "but

not now." Since the gate to the Law remains open and the doorman steps

to

the side, the man bends down to look through the gate into the

interior. When

the doorman notices this, he laughs and says, "If it tempts you so

much,

try to get in despite my warning. But know this: I'm powerful, and I'm

only the

lowliest doorman. In every chamber stands another doorman, each more

powerful

than the one before. Though powerful myself, the very gaze of the third

is more

than I can endure." The man from the country hadn't anticipated such

difficulties; the Law is supposedly accessible to anyone at any time,

he

thinks, but now, as he looks at the doorman in his fur coat more

carefully, at

his large, pointed nose, the long, thick, black Cossack beard, he

decides to

continue waiting until he receives permission to enter. The doorman

gives him a

stool and lets him sit down to the side of the door. There he sits for

days and

years. He makes many attempts to be admitted and wears out the doorman

with his

pleas. The doorman often subjects him to a series of questions, asks

him about

his home and many other things, but they're questions posed in a

detached way,

the sort that great lords pose, and in the end he always repeats that

he still

can't grant him entry. The man, who had fully equipped himself for his

journey,

uses everything he has, no matter how valuable, to bribe the doorman.

The

latter accepts everything but says at the same time: "I'm only

accepting

this so that you won't think that you've overlooked something." Over

the

many years the man watches the doorman almost constantly. He forgets

about the

other doormen, and this first one seems to him to be the only obstacle

between

him and access to the Law. He curses his bad luck, in the first years

recklessly and loudly; later, as he grows old, he continues only to

grumble to

himself quietly. He becomes like a child, and since in his perennial

observations of the doorman he has come to know even the fleas in the

collar of

his fur coat, he even asks the fleas to help him change the doorman's

mind.

Finally, his vision becomes weak, and he doesn't know whether it's

getting

darker around him or his eyes are only deceiving him. But now he

recognizes in

the darkness a brilliance which radiates inextinguishably from the door

of the

Law. He doesn't have much longer to live now. As he's near the end, all

of his

experiences of the entire time culminate in a question that he hasn't

yet asked

the doorman. Since he can no longer raise his stiffening body, he

motions to

him. The doorman must bend very low for him since their difference in

height

has changed much to the latter's disadvantage. "What do you want to

know

now?" asks the doorman. "You're insatiable." "Everyone

strives for the Law," says the man. "How is it that in these many

years no one except me has asked to be admitted?" The doorman realizes

that the man is already near the end, and to reach his failing ears he

roars at

him: "No one else could be admitted here because this entrance was for

you

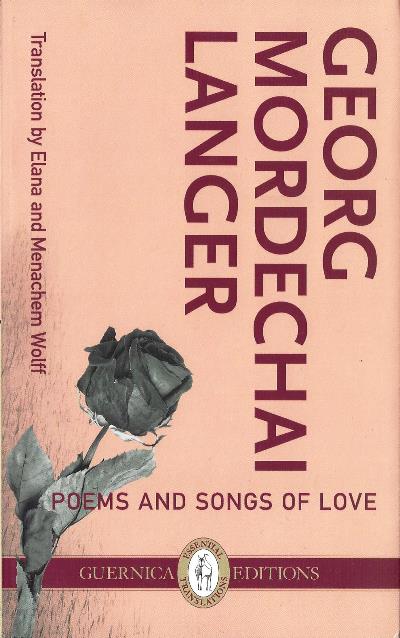

alone. I'll now go and close it." Trước Pháp Luật Trước Pháp Luật có tên gác cửa. Một người nhà quê tới và xin phép vô, nhưng tên gác nói, ta không thể cho phép. Người nhà quê suy nghĩ, rồi hỏi, liệu lát nữa, có được không. Tên gác nói, “có thể”, nhưng “lúc này thì chưa”. Bởi là vì cửa mở, và tên gác thì đứng né qua 1 bên, cho nên người nhà quê bèn cúi xuống dòm vô bên trong. Tên gác bèn cười và nói, "Nếu mi thèm như thế, thì cần gì ta, cứ vô đại đi. Nhưng hãy nhớ điều này, ta có quyền, và ta chỉ là tên gác cửa thấp nhất. Ở mỗi phòng thì có 1 tên gác cửa, mỗi tên như thế có quyền hơn tên trước. Có quyền như ta đây, vậy mà cái nhìn của tên thứ ba, ta không chịu nổi.” Người đàn ông nhà quê chưa từng đụng những khó khăn như thế; Pháp Luật thì ai cũng có thể tới được, vào bất cứ lúc nào, anh ta nghĩ, nhưng bây giờ, nhìn tên gác cửa trong cái áo khoác bằng lông thú một cách kỹ luỡng, cái mũi to, nhọn, bộ râu Cossack đen, dài, dầy, anh bèn quyết định tiếp tục đợi tới khi được phép vô. Người gác cửa cho anh ta một cái ghế đẩu, và anh ngồi xuống kế bên cửa. Anh ta ngồi như thế, những ngày, rồi những năm. Anh ta bày điều này, kế nọ để mong được cho phép, và làm tên gác mệt nhoài với những lời khẩn cầu của mình. Tên gác thì lại trút lên anh ta hàng lố câu hỏi, nhà cửa, gia đình ra làm sao, và nhiều điều khác nữa, nhưng theo kiểu, hỏi cho có, như mấy ông lớn thường làm, và sau cùng, luôn lập lại, anh ta không thể cho phép. Người nhà quê, do đã trang bị thật tới chỉ, cho chuyến đi, bèn sử dụng tất cả những gì mà anh ta có, dù quí giá tới mức nào, để hối lộ tên gác. Tên này nhận hết mọi thứ, nhưng vẫn nói, lần nào cũng vậy: "Ta nhận như thế này là để cho mi đừng nghĩ, mi bỏ qua một điều gì.” Nhiều năm qua đi, người nhà quê hầu như lúc nào cũng quan sát tên gác cửa. Anh ta quên những tên gác cửa khác, và tên này có vẻ là trở ngại độc nhất, giữa anh, và tới với Pháp Luật. Anh ta trù ẻo tên gác, những năm đầu thật dữ dằn, thật lớn tiếng; sau đó, trở nên già, anh chỉ lặng lẽ tiếp tục gầm gừ với chính mình. Anh trở thành, như 1 đứa con nít…  Cuốn này quái quá, một nửa dành cho Kafka, một nửa, cho Langer, bạn của Kafka. Gấu thú thực chưa từng nghe đến tên của tác giả này. Phần thơ & nhạc, song ngữ [tiếng Hebreu] Phần Kafka, bản dịch mới Gõ Google, ra bài này: Kafka &

Langer: An Unusually Complex Friendship

IN FRONT OF

THE LAW IN FRONT OF

the Law stands a doorman. A man from the country comes to this doorman

and asks

to be admitted to the Law, but the doorman says that he can't allow him

to

enter. The man reflects on this and then asks if he can assume that

he'll be

allowed to enter later. "It's possible," says the doorman, "but

not now." Since the gate to the Law remains open and the doorman steps

to

the side, the man bends down to look through the gate into the

interior. When

the doorman notices this, he laughs and says, "If it tempts you so

much,

try to get in despite my warning. But know this: I'm powerful, and I'm

only the

lowliest doorman. In every chamber stands another doorman, each more

powerful

than the one before. Though powerful myself, the very gaze of the third

is more

than I can endure." The man from the country hadn't anticipated such

difficulties; the Law is supposedly accessible to anyone at any time,

he

thinks, but now, as he looks at the doorman in his fur coat more

carefully, at

his large, pointed nose, the long, thick, black Cossack beard, he

decides to

continue waiting until he receives permission to enter. The doorman

gives him a

stool and lets him sit down to the side of the door. There he sits for

days and

years. He makes many attempts to be admitted and wears out the doorman

with his

pleas. The doorman often subjects him to a series of questions, asks

him about

his home and many other things, but they're questions posed in a

detached way,

the sort that great lords pose, and in the end he always repeats that

he still

can't grant him entry. The man, who had fully equipped himself for his

journey,

uses everything he has, no matter how valuable, to bribe the doorman.

The

latter accepts everything but says at the same time: "I'm only

accepting

this so that you won't think that you've overlooked something." Over

the

many years the man watches the doorman almost constantly. He forgets

about the

other doormen, and this first one seems to him to be the only obstacle

between

him and access to the Law. He curses his bad luck, in the first years

recklessly and loudly; later, as he grows old, he continues only to

grumble to

himself quietly. He becomes like a child, and since in his perennial

observations of the doorman he has come to know even the fleas in the

collar of

his fur coat, he even asks the fleas to help him change the doorman's

mind.

Finally, his vision becomes weak, and he doesn't know whether it's

getting

darker around him or his eyes are only deceiving him. But now he

recognizes in

the darkness a brilliance which radiates inextinguishably from the door

of the

Law. He doesn't have much longer to live now. As he's near the end, all

of his

experiences of the entire time culminate in a question that he hasn't

yet asked

the doorman. Since he can no longer raise his stiffening body, he

motions to

him. The doorman must bend very low for him since their difference in

height

has changed much to the latter's disadvantage. "What do you want to

know

now?" asks the doorman. "You're insatiable." "Everyone

strives for the Law," says the man. "How is it that in these many

years no one except me has asked to be admitted?" The doorman realizes

that the man is already near the end, and to reach his failing ears he

roars at

him: "No one else could be admitted here because this entrance was for

you

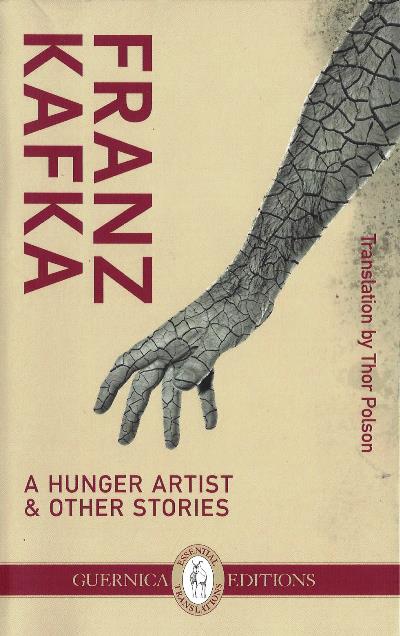

alone. I'll now go and close it." TRANSLATOR'S

NOTES Like the

work of any other seminal figure in world literature, Franz Kafka's

writing

defies any attempt at a tidy categorization. One can look for

antecedents in

his writing, one can compare his writing with that of his

contemporaries, and

one can trace the Nachleben of his

writings and their influence on later writers, but all of this is

doomed to

remain an ill-considered construct, a theoretical crowbar used to

wrench him

willfully into an arbitrary context of some kind. What to do with Franz

Kafka?

This question is best left to literary scholars to ponder, but I can't

help but

think that Kafka himself would only react with his typically bemused

smile at

their ongoing efforts to define him. I've been working on this

translation project intermittently

since 1994. The inspiration came to me from the Austrian writer Stefan

Zweig,

who considered his translations of Baudelaire, Verlaine, and Verhaeren

to be

integral to his own development as a writer. In short, Zweig believed

that

becoming intimately acquainted with a foreign author's writing style is

invaluable in developing one's own and that there's no better way of

doing so

than by translating that author's writing. Because of his immense

appeal to me,

Kafka was an obvious choice in my case, and I chose these two

collections in

particular (Ein Landarzt and Ein

Hungerkunstler) because they don't

tend to receive as much attention as some of Kafka's other works. In

any case,

Zweig's point is well taken: like James Joyce, Kafka was a consummate

craftsman, and what I've learned from having so minutely examined his

writing

style will certainly serve me well as I return to writing my own

fiction. I

assert that a translator can only be defined as an arbitrary

collaborator

working figuratively with an absent author,' living or dead, who more

often

than not and for various reasons has' nothing whatsoever to do with the

translation process. This was obviously true in this case, and I can

describe

my approach to the process in the following way: 1. 2.

With all of this and other factors in

mind, including various editorial considerations (see below), I

continued to

subject the text to repeated revisions while referring frequently to

the German

as a corrective in cases where my translation wasn't clear or seemed to

lack

cohesion. This took time. 3.

At various points during the process I

consulted native speakers for help in translating a few of the thornier

passages. They often found these passages just as puzzling as they were

to me,

a fact attributable to the language of the time and to what I would

call a

studied ambiguity on the part of the author, a hallmark of good prose

and

poetry in the hands of a capable author. (After all, a poem isn't an

automobile

manual.) Finally, being able to refer to words and collocations

accessible

through various Internet search engines was also of considerable help

in

answering these questions. This book,

then, is the result of countless hours of work, with painstaking

attention

given to every detail. If asked, I could in fact offer a carefully

reasoned argument

for every single word choice, but as in the case of any translation,

there will

always remain a few problems, things that have been overlooked and even

mistranslated. As a language teacher, for example, I've regularly

presented my

students with a series of translations of passages from German, Greek,

and

Latin authors, and there are always problems of some kind (the very

purpose of

the exercise, of course). That's inevitable, but in this case I'd like

to think

that almost 100 per cent of what you've read is what Franz Kafka

intended to

convey. For further thoughts on the process of translating, I would

recommend

Douglas Hofstadter's "Translator, Trader: An Essay on the Pleasantly

Pervasive Paradoxes of Translation", co- bound with his translation of

Francoise Sagan's La Chamade (Basic

Books, 2009). I once spoke to an Italian

translator at a Goethe Institute

in Germany who pointed out that there's no money to be made in

translating and

that, like the process involved in the creation of the very literature

we

translate, it's ultimately a labor of love. That's certainly true in

this case,

and I've often asked myself why Kafka appeals to me so much. His

exquisite

sense of absurdity is certainly one factor, and much of his writing

(e.g. ''A

Report for an Academy" in this collection) amuses me. It's Kafka's

sensitivity and delicacy, however, that appeal to me more than anything

else.

These qualities can be clearly seen, for example, in the piece "Seated

in

the Gallery", in which the narrator is reduced to tears by the sheer

beauty of a woman on horseback. To Kafka, the world's beauty must have

been

every bit as excruciating as its darker side, and I can only see his

almost

compulsive need to write as well as the occasionally grotesque quality

of his

writing as being coping mechanisms which allowed him to receive,

process, and

ultimately accept the many conflicting and disturbing impressions

encountered

in his everyday life. In the summer of 2009 I had the opportunity to

visit both

the house in which Kafka was born and the house in which he died of

tuberculosis, and the visit to the latter (including a terse, bizarre

conversation at the door with a Hausmeister

who could very well have just stepped out of a Kafka narrative) moved

me deeply

as I viewed the handful of items displayed in a sparsely furnished

room. Franz

Kafka must have had a very gentle soul. The texts used are those

which appear in Paul Raabe's edition

of Kafka's stories: Franz Kafka: Samtliche

Erzahlungen (Fischer Taschenbuchverlag, 1970). Any changes in

Kafka's

sentence structure, phrasing, and punctuation have been made for the

sake of

clarity within the English idiom and were undertaken only after a

protracted

consideration of every conceivable option. Some additional comments

follow: 1.

As is true of all German

prose, Kafka's paragraphs can be at

times very long (as in "Josephine the Singer") or very short (as in

"Jackals and Arabs"). These have in all cases been retained.

Furthermore, I see the author's use of paragraphs and punctuation in

general as

indicating a clear form of prioritization ranging from the paragraph

through

the period, semi-colon and colon to the comma. 2.

Some of Kafka's sentences are

extremely long, and their structure and tempo can be characterized in

turn by

varying degrees of parataxis, hypotaxis, and asyndeton. In a very small

number

of cases I have chosen to break up a long sentence into two shorter

ones.

Almost all of the incomplete sentences have been left intact. 3.

I have followed the convention according

to which interior monologues appear in italics in order to set them

apart from

direct discourse and from the narrative per

se. 4.

On occasion, Clauses have been

reversed for the sake of clarity. Embedded clauses (normally involving

parenthetical

information) have only rarely been repositioned within the given

sentence. 5.

Kafka makes abundant use of

semi-colons, and his usage differs from the English usage in that it

occasionally causes a subordinate clause to dangle. In general, I have

chosen

to leave this punctuation unaltered. 6.

Single dashes are used by Kafka to set

off parts of sentences and paragraphs from the preceding text. These

have been

retained. Double dashes have been replaced by parentheses or commas so

that no

confusion will arise from interpreting the first dash as a colon. 7.

Kafka occasionally omits question

marks in direct questions. I have inserted them in accordance with

standard

English usage. 8.

Comma splices are perfectly acceptable

at all levels of written German. Where encountered, I have replaced the

given

comma with a colon, semi-colon, or period. (I have occasionally, though

rarely,

retained the comma and added a conjunction, and in one instance an

appositive

was formed by repeating the noun after the comma and adding a relative

clause.)

Comma splices and other forms of asyndeton have been occasionally

retained for

effect, a choice determined in each case by the given context. 9.

With very few exceptions (e.g. in ''A

Report for an Academy"), 1 have chosen to use contractions freely

throughout this translation as being reflective of the normally

familiar tone

used by the narrator. 10.

Kafka's use of the historical present

(e.g. in "A Country Doctor" and "A Message from the

Emperor") can seem rather abrupt at times, but the tenses have been

left

unaltered. In closing,

I wish to thank Mag. Walter Neumayr, Mag. Martha Schofbeck, Irene

Augsburger,

and Nils Weisensee for having helped me with some of the more difficult

and

enigmatic passages in the text, and my sincerest gratitude also goes to

the

reviewers whose comments appear below and on my website

(www.thorpolson.com).

Many thanks to you all.

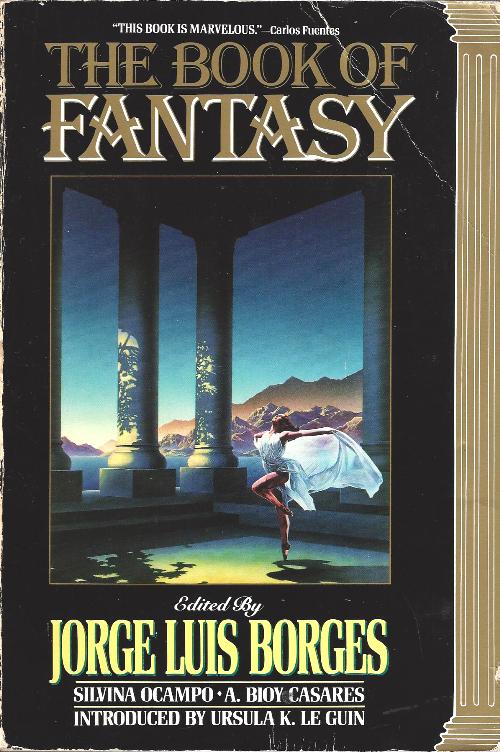

Vô tiệm sách cũ, vớ được

cuốn lạ, Borges biên tập. GCC chưa từng nghe tới cuốn này! Kafka đóng

góp hai truyện, Josephine và Trước Pháp Luật. Trang Tử, Bướm mơ người

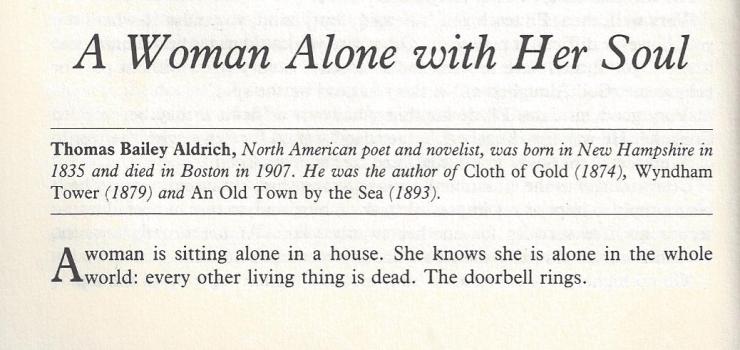

hay người mơ bướm. Một truyện trong cuốn sách.  The

Shadow of the Players

In one of the tales which

make up the series of the Mabinogion,

two enemy kings play chess while in a nearby valley their respective

armies battle and destroy each other. Messengers arrive with reports of

the battle; the kings do not seem to hear them and, bent over the

silver chessboard, they move the gold pieces. Gradually it becomes

apparent that the vicissitudes of the battle follow the vicissitudes of

the game. Toward dusk, one of the kings overturns the board because he

has been checkmated, and presently a blood-spattered horseman comes to

tell him: 'Your army is in flight. You have lost the kingdom.' Bóng Kỳ

Thủ

Một trong những truyện của

chuỗi truyện Mabinogion, hai ông vua kẻ thù ngồi chơi cờ,

trong lúc trong thung lũng kế đó, hai đạo binh của họ quần

thảo, làm thịt lẫn nhau. Giao liên, thiên sứ… liên

tiếp mang tin về, họ đếch thèm nghe, chúi mũi vô mấy con cờ bằng

vàng. Rõ ràng là tuồng ảo hoá bày ra ở thung lũng nhập thành

một với tuồng cờ tướng. Sau cùng, vào lúc chập tối, 1 ông

vua xô đổ bàn cờ, khi bị chiếu bí, đúng lúc đó, tên kỵ sĩ từ

chiến trường lao về, thưa hoàng thượng, VC lấy mẹ mất Xề Gòn

rồi! Hà, hà!

Before the

Law stands a doorkeeper. To this doorkeeper there comes a man from the

country

and prays for admittance to the Law. But the doorkeeper says that he

cannot

grant admittance at the moment. The man thinks it over and then asks if

he will

be allowed in later. 'It is possible,' says the doorkeeper, 'but not at

the

moment.' Since the gate stands open, as usual, and the doorkeeper steps

to one

side, the man stoops to peer through the gateway into the interior.

Observing

that, the doorkeeper laughs and says: 'If you are so drawn to it, just

try to

go in despite my veto. But take note: I am powerful. And I am only the

least of

the doorkeepers. From hall to hall there is one doorkeeper after

another, each

more powerful than the last. The third doorkeeper is already so

terrible that

even I cannot bear to look at him.' These are difficulties the man from

the country

has not expected; the Law, he thinks, should surely be accessible at

all times

and to everyone, but as he now takes a closer look at the doorkeeper in

his fur

coat, with his big sharp nose and long, thin, black Tartar beard, he

decides that

it is better to wait until he gets permission to enter. The doorkeeper

gives him

a stool and lets him sit down at one side of the door. There he sits

for days and

years. He makes many attempts to be admitted, and wearies the

doorkeeper by his

importunity. The doorkeeper frequently has little interviews with him,

asking

him questions about his home and many other things, but the questions

are put

indifferently, as great lords put them, and always finish with the

statement

that he cannot be let in yet. The man, who has furnished himself with

many

things for his journey, sacrifices all he has, however valuable, to

bribe the doorkeeper.

The doorkeeper accepts everything, but always with the remark: 'I am

only

taking it to keep you from thinking you have omitted anything.' During

these

many years the man fixes his attention almost continuously on the

doorkeeper.

He forgets the other doorkeepers, and this first one seems to him the

sole

obstacle preventing access to the Law. He curses his bad luck, in his

early

years boldly and loudly; later, as he grows old, he only grumbles to

himself.

He becomes childish, and since in his yearlong contemplation of the

doorkeeper

he has come to know even the fleas on his fur collar, he begs the fleas

as well

to help him and to change the doorkeeper's mind. At length his eyesight

begins

to fail, and he does not know whether the world is really darker or

whether his

eyes are only deceiving him. Yet in his darkness he is now aware of a

radiance

that streams inextinguishably from the gateway of the Law. Now he has

not very

long to live. Before he dies, all his experiences in these long years

gather

themselves in his head to one point, a question he has not yet asked

the doorkeeper.

He waves him nearer, since he can no longer raise his stiffening body.

The

doorkeeper has to bend low towards him, much to the man's disadvantage.

'What

do you want to know now?' asks the doorkeeper; 'you are insatiable.'

'Everyone

strives to reach the Law,' says the man, 'so how does it happen that

for all

these many years no one but myself has ever begged for admittance?' The

doorkeeper recognizes that the man has reached his end, and, to let his

failing

senses catch the words, roars in his ear: 'No one else could ever be

admitted

here, since this gate was made only for you. I am now going to shut

it.' Frank Kafka The Book of

Fantasy Edited by Jorge Luis Borges, Silvina Ocampo, A. Bloy Casares A collection of classic

fantasy stories which resulted from a chance conversation between three

friends in Buenos Aires in 1937. The friends were Jorge Luis Borges,

Adolfo Bioy Casares and his wife Silvina Ocampo and they decided to

gather together their favourite stories.

|