|

|

Hãy đốt cuốn

sách này

Freedom

to Write

By Orhan Pamuk

The following was given on

April 25 as the inaugural PEN Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Memorial

Lecture.

Tự Do Viết.

Đọc tại PEN cùng dịp với

DTH.

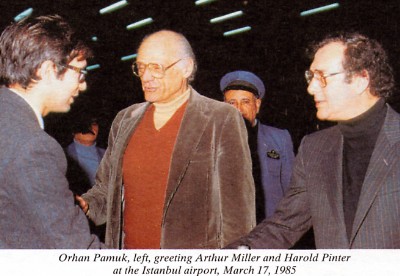

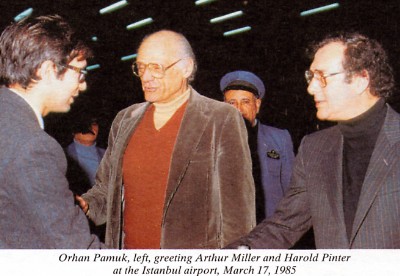

In March 1985 Arthur

Miller and Harold Pinter made a trip together to Istanbul. At the time,

they were perhaps the two most important names in world theater, but

unfortunately, it was not a play or a literary event that brought them

to Istanbul...'I

stand by my words. And even more, I stand by my right to say them...'

When

the acclaimed Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk recalled his country's mass

killing of Armenians, he was forced to flee abroad. As he prepares to

accept a peace award in Frankfurt, he tells Maureen Freely why he had

to break his nation's biggest taboo.

"Tôi giữ vững những lời nói của tôi. Tôi giữ vững quyền của tôi, được

nói những lời đó ra trước bàn dân thiên hạ."

Nhưng

ông ta nói gì vậy?

Pamuk said that 'a million Armenians and 30,000 Kurds were killed in

this country and I'm the only one who dares to talk about it'.

Ông

nói, "một triệu người Armenians, và 30 ngàn người Kurds

đã bị làm cỏ, trong xứ sở này, và tôi là người độc nhất dám nói ra

chuyện làm cỏ này"

Sunday

October 23, 2005

The Observer [Guardian online]

Ông

là nhà văn Thổ Nhĩ Kỳ, và đã xì ra vụ trên, với một tờ báo ở Thuỵ Sĩ,

vì vụ này mà phải chạy trốn quê hương. Ông nhà nước nói, có vài trăm

người bị chết thôi mà, thằng cha đó nói hoảng, tố ẩu!

Gấu

bỗng nghĩ đến vụ Mậu Thân.

Vụ

này, cũng chưa từng xẩy ra!

Mà

nếu có xẩy ra, thì cũng chỉ vài thằng Nguỵ có nợ máu với nhân dân, bị

trừng trị, và nếu như có hàng ngàn người dân Huế bị giết, thì đúng là

thằng Nguỵ nó giết, rồi đổ tội cho Cách Mạng!

Cách Mạng làm sao lại giết người, nhất là những thường dân vô tội?

Nhưng

giá mà có một ông nhà văn 'Cách Mạng nào đó', thí dụ như me-xừ gì gì

đó, bỗng hùng hồn tuyên bố như ông nhà văn Thổ kia, thì thú biết

mấy! (1)

Cuộc chiến Mít, là do VC phịa ra, rồi thực hiện nó, với cái giá thật là

khủng khiếp về con số người chết, trong cuộc chiến, sau đó, và 1 nước

Mít như hiện nay.

I have personally known writers who have

chosen to raise forbidden topics purely because they were forbidden. I

think I am no different. Because when another writer in another house

is not free, no writer is free. This, indeed, is the spirit that

informs the solidarity felt by PEN, by writers all over the world.

Sometimes my friends rightly tell me or someone else, "You shouldn't

have put it quite like that; if only you had worded it like this, in a

way that no one would find offensive, you wouldn't be in so much

trouble now." But to change one's words and package them in a way that

will be acceptable to everyone in a repressed culture, and to become

skilled in this arena, is a bit like smuggling forbidden goods through

customs, and as such, it is shaming and degrading.

Cá nhân tôi, tôi biết, có

những nhà văn dám đụng vô những đề tài cấm đoán, hoàn toàn do, đúng chỉ

vì, trong trắng như 1 lần sự thực [TTT], purely, chúng là những đề tài

bị cấm đoán, Tôi nghĩ, tôi cũng thế. Bởi là vì khi một nhà văn khác,

trong 1 căn nhà khác, không tự do, thì đếch có một nhà văn nào tự do.

Pamuk

Đúng là 'bad' boy!

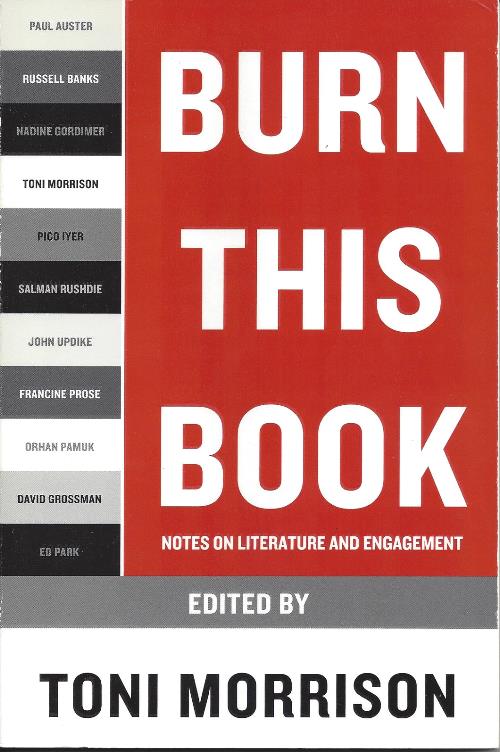

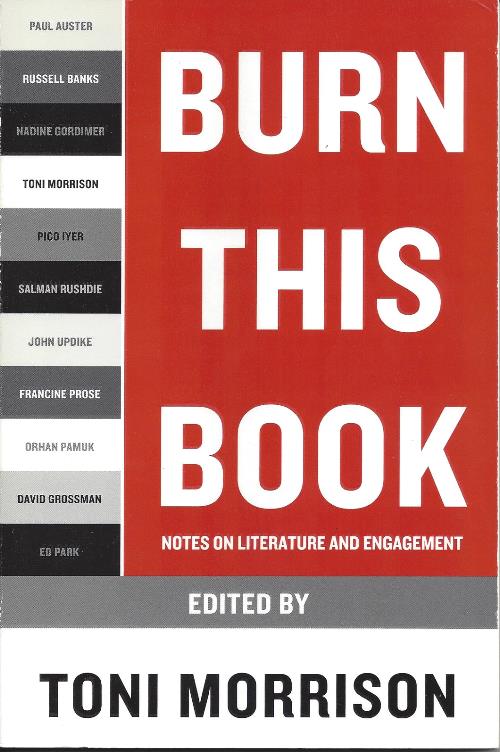

Hãy đốt cuốn sách này!

May quá, có mấy bài đã

giới thiệu trên TV, của Salman Rushdie [Ghi chú về Viết và Nước, Notes on Writing

and Nation], David Grossman [Viết

trong Bóng Tối]. Sẽ giới thiệu tiếp bài của Toni Morrison: Peril:

Hiểm nguy

Peril

Toni Morrison

Authoritarian regimes,

dictators, despots are often, but not always, fools. But none is

foolish enough to give perceptive, dissident writers free range to

publish their judgments or follow their creative instincts. They know

they do so at their own peril. They are not stupid enough to abandon

control (overt or insidious) over media. Their methods include

surveillance, censorship, arrest, even slaughter of those writers

informing and disturbing the public. Writers who are unsettling,

calling into question, taking another, deeper look.

Writers-journalists, essayists, bloggers, poets, playwrights-can

disturb the social oppression that functions like a coma on the

population, a coma despots call peace; and they stanch the blood flow

of war that hawks and profiteers thrill to.

That is their peril.

Ours is of another sort.

How bleak, unlivable, insufferable existence becomes

when we are deprived of artwork. That the life and work of writers

facing peril must be protected is urgent, but along with that urgency

we should remind ourselves that their absence, the choking off of a

writer's work its cruel amputation, is of equal peril to us. The rescue

we extend to them is a generosity to ourselves.

We all know nations that can be identified by the

flight of writers from their shores. These are regimes whose fear of

unmonitored writing is justified because truth is trouble. It is

trouble for the warmonger, the torturer, the corporate thief, the

political hack, the corrupt justice system, and for a comatose public.

Unpersecuted, unjailed, unharassed writers are trouble for the ignorant

bully, the sly racist, and the predators feeding off the world's

resources. The alarm, the disquiet, writers raise is instructive

because it is open and vulnerable, because if unpoliced it is

threatening. Therefore the historical suppression of writers is the

earliest harbinger of the steady peeling away of additional rights and

liberties that will follow. The history of persecuted writers is as

long as the history of literature itself. And the efforts to censor,

starve, regulate, and annihilate us are clear signs that something

important has taken place. Cultural and political forces can sweep

clean all but the "safe," all but state-approved art.

I have been told that there are two human responses

to the perception of chaos: naming and violence. When the chaos is

simply the unknown, the naming can be accomplished effortlessly-a new

species, star, formula, equation, prognosis. There is also mapping,

charting, or devising proper nouns for unnamed or stripped-of-names

geography, landscape, or population. When chaos resists, either by

reforming itself or by rebelling against imposed order, violence is

understood to be the most frequent response and the most rational when

confronting the unknown, the catastrophic, the wild, wanton, or

incorrigible. Rational responses may be censure, incarceration in

holding camps, prisons, or death, singly or in war. There is however a

third response to chaos, which I have not heard about, which is

stillness. Such stillness can be passivity and dumbfoundedness; it can

be paralytic fear. But it can also be art. Those writers plying their

craft near to or far from the throne of raw power, of military power,

of empire building and counting-houses, writers who construct meaning

in the face of chaos must be nurtured, protected. And it is right that

such protection be initiated by other writers. And it is imperative not

only to save the besieged writers but to save ourselves. The thought

that leads me to contemplate with dread the erasure of other voices, of

unwritten novels, poems whispered or swallowed for fear of being

overheard by the wrong people, outlawed languages flourishing

underground, essayists' questions challenging authority never being

posed, un-staged plays, canceled films-that thought is a nightmare. As

though a whole universe is being described in invisible ink.

Certain kinds of trauma visited on peoples are so

deep, so cruel, that unlike money, unlike vengeance, even unlike

justice, or rights, or the goodwill of others, only writers can

translate such trauma and turn sorrow into meaning, sharpening the

moral imagination.

A writer's life and work are not a gift to mankind;

they are its necessity.

TM

Cuộc đời và tác phẩm của một nhà văn đếch phải là một món quà cho nhân

loại. Chúng là sự cần thiết của nó.

|

|