|

Advertisement

|

|

|

Xác Đại Dâm Tăng

Rasputin

Trong lời mở ra cuốn

tiểu sử Solzhenitsyn, D.M. Thomas nhớ lại cảnh tượng, ngồi uống vodka với

một tay mật vụ, cựu đại tá KGB, đã

về hưu, và được nhà nước ban cho nhiệm vụ 'đánh bóng'

hình ảnh đất mẹ, ở hải ngoại.

Cả hai ngồi tại khách sạn

"Hình ảnh nào ư?", ông ta gật gù, nhìn ra Vịnh Phần Lan.

Vài tuần trước

đó, con tầu phà

Nhưng hình ảnh khởi đầu?

A dubious account of the gruesome murder of Grigory Rasputin

Lost Splendour and the Death of Rasputin. By Felix Yusupov. Adelphi; 304 pages; 288 pages; £12.99.

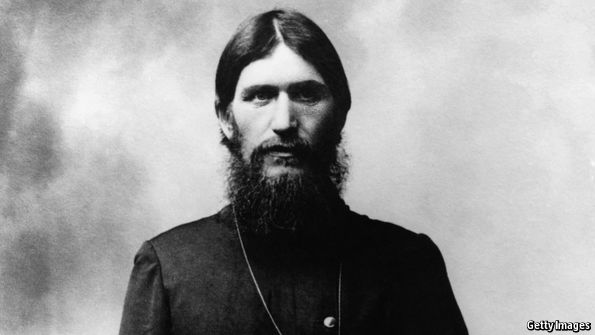

FEW murderers boast about their crimes. But Prince Felix Yusupov was no ordinary killer, and his prey—the “mad monk” Grigory Rasputin—no ordinary victim. On the centenary of the assassination of the Romanovs’ Svengali on December 30th, the republication of Yusupov’s memoir provides a timely glimpse into the charmed, doomed world of the Russian aristocracy, and its hectic collapse amid the Bolshevik revolution.

His grasp of facts is shaky and his motives self-serving. But the princely capers make a gripping, if sometimes repellent, read. Yusupov’s penchants for transvestite dressing and wild evenings with gypsies show an interestingly unconventional side. His childish pranks (such as letting rabbits and chickens loose in the Carlton Club in London) were much funnier for the perpetrator than the hard-pressed servants who had to clear them up.

|

Advertisement

|

|

|

The most important part of the book is the description of Rasputin’s assassination. The humble Siberian peasant bewitched Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, the Tsarina, with his apparently miraculous powers. His aristocratic assassins, recruited by Yusupov, believed Russia, misruled to the point of collapse, could be saved only if the royal family could be freed of the faith-healer’s malign influence.

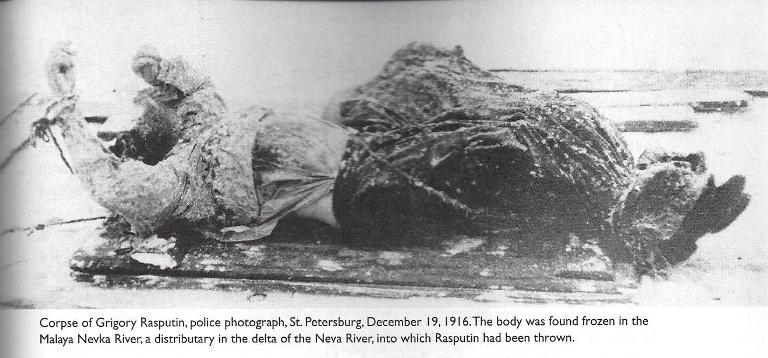

They cast lots, obtained some cyanide, added it to cakes and wine, and tricked Rasputin, whom Yusupov had befriended earlier, into joining them for dinner. The trusting, unarmed guest consumed the poison, but it had no effect. Yusupov, having first advised him to pray, then shot him in the chest at point-blank range. Yet a few minutes later he rose, foaming at the mouth, “raised from the dead by the powers of evil...I realised now who Rasputin really was...the reincarnation of Satan himself.” After several more shots were fired, the assassins dumped the body in a river.

Much of this account, like the prince’s motives, is questionable, The lurid tone may have been useful: the Yusupovs lost most of their vast fortune in the revolution. Other sources suggest that the poison was fake; Rasputin was killed by three shots, but the tale of his satanic resurrection is wholly uncorroborated. Rasputin’s real story is painstakingly told in a compendious new book by Douglas Smith, an American scholar of Russian history. But Prince Yusupov’s account is gripping.