Contents

Introduction

by Alastair Reid

The Divine

Comedy

Nightmares

The Thousand

and One Nights

Buddhism

Poetry

The Kabbalah

Blindness

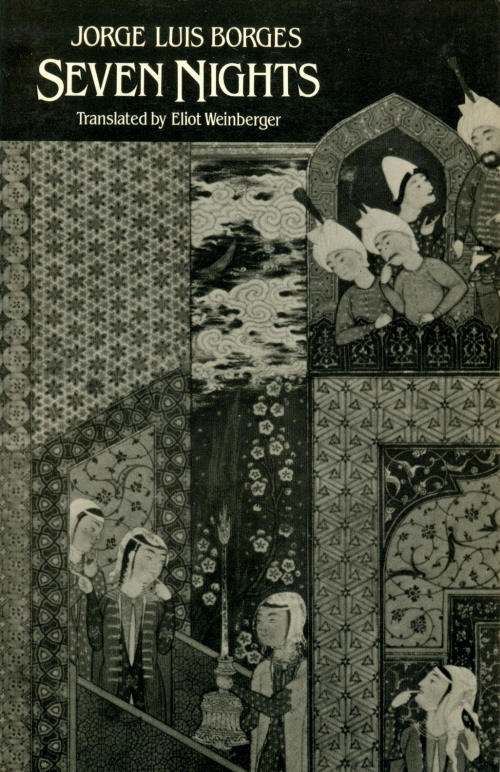

Ngàn

Lẻ Một Đêm

Seven Nights là cuốn Borges đầu

tiên Gấu đọc, những ngày mới qua

Xứ Lạnh.

Mượn thư viện.

Chắc

cũng thẻ thư viện đầu tiên.

CHAPTER

THIRTY-THREE

To Read or

Not to Read:

The Thousand

and One Nights

I read my

first tales from the Thousand and One Nights when I was seven. I had

just

finished my first year of primary school, and my brother and I had gone

to

spend the summer in Geneva, Switzerland, where my parents had moved

after my

father took a job there. Among the books my aunt had given us on

leaving

Istanbul, to help us improve our reading over the summer, was a

selection of

stories from the Thousand and One Nights. It was a beautifully bound

volume,

printed on high- quality paper, and I remember reading it four or five

times

over the course of the summer. When it was very hot, I would go to my

room for a

rest after lunch; stretching out on my bed, I would read the same

stories over

and over. Our apartment was one street away from the shores of Lake

Geneva, and

as a light breeze wafted in through the open window and the strains of

the

beggar's accordion drifted up from the empty lot behind our house, I

would

drift off to lose myself in the land of Aladdin's Lamp and Ali Baba's

Forty

Thieves.

What was the name of the country I visited? My first

explorations told

me it was alien and faraway, more primitive than our world but part of

an

enchanted realm. You could walk down any street in Istanbul and meet

people

with the same names as the heroes, and perhaps that made me feel a

little

closer to them, but I saw nothing of my world in their stories; perhaps

life

was like this in the most remote villages of Anatolia but not in modem

Istanbul. So the first time I read the Thousand and One Nights, I read

it as a

Western child would, amazed at the marvels of the East. 1 was not to

know that

its stories had long ago filtered into our culture from India, Arabia,

and

Iran; or that Istanbul, the city of my birth, was in many ways a living

testament to the tradition« from which these magnificent stories arose;

or that

their conventions – the lies, tricks, and deceptions, the lovers and

betrayers,

the disguises, twists, and surprises-were deeply woven into my native

city's

tangled and mysterious soul. It was only later that I discovered-from

other

books-that the first stories I read from the Thousand and One Nights

had not

been culled from the ancient manuscripts that Antoine Galland, the

French

transla- tor, and the tales' first anthologizer, claimed to have

acquired in

Syria. Galland did not take Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves or Aladdin's

Magic Lamp

from a book, he heard them from a Christian Arab named Hanna Diyab and

only

wrote them down much later, when he was putting together his anthology.

This brings

us to the real subject: The Thousand and One Nights is a marvel of

Eastern

literature. But because we live in a culture that has severed its links

with

its own cultural heritage and forgotten what it owes to India and Iran,

surrendering instead to the jolts of Western literature, it came back

to us via

Europe. Though it was published in many Western languages-sometimes

translated

by the finest minds of the age and sometimes by the strangest, most

deranged,

and most pedantic-it is Antoine Galland's work that was the most

celebrated. At

the same time, the anthology that Galland began to publish in 1704 is

the most

influential, most widely read, and most enduring. One could go so far

as to say

it was the first time this endless chain of tales had appeared as a

finite entity,

and the edition was itself responsible for the worldwide fame these

stories

achieved. The anthology exerted a rich and powerful influence on

European

writing for the better part of a century. The winds of the Thousand and

One

Nights rustle through the pages of Stendhal, Coleridge, De Quincey, and

Poe.

But if we read the anthology from cover to cover, we can also see how

that

influence is bounded. It is preoccupied mostly with what we might call

the

"mystical East"-the stories are replete with miracles, strange and

supernatural occurrences, and scenes of terror-but there is more to the

Thousand and One Nights than that.

I could see this more clearly when I returned

to the Thousand and One Nights in my twenties. The translation I read

then was

by Raif Karadag, who reintroduced the book to the Turkish public in the

1950s. Of

course-like most readers-I didn't read it from cover to cover,

preferring to

wander from story to story as my curiosity took me. On second reading,

the book

troubled and provoked me. Even as I raced from page to page, gripped by

suspense

I resented and sometimes truly hated what I was reading. That said, I

never

felt I was reading out of a sense of duty, as we sometimes do when

reading

classics; I read with great interest, while hating the fact that I was

interested.

Thirty years

later, I think I know what it is that was bothering me so much: In most

of the

stories, men and women are engaged in a perpetual war of deception. I

was

unnerved by their never-ending round of games, tricks, betrayals, and

provocations. In the world of the Thousand and One Nights, no woman can

ever be

trusted. You can't believe a thing women say; they do nothing but trick

men

with their little games and ruses. It begins on the first page, as

Sheherazade

keeps a loveless man from killing her by entrancing him with stories.

If this

pattern is repeated through the book, it can only reflect how deeply

and

fundamentally men feared women in the culture that produced it. This is

quite

consistent with the fact that the weapon women use most successfully is

their

sexual charm. In this sense, the Thousand and One Nights is a powerful

expression

of the most potent fear gripping men of its era: that women might

abandon them,

cuckold them, and condemn them to solitude. The story that provokes

this fear

most intensely-and affords the most masochistic pleasure-is the story

of the

sultan who watches his entire harem cuckold him with their black

slaves. It

confirms all the worst male fears and prejudices about the female sex,

and so

it is no accident that popular Turkish novelists of the modem period,

and even

politically committed "social realists" like Kemal Tahir, chose to

milk this tale for all they could. But when I was in my twenties, and

awash in typically

male fears about never-to-be-trusted women, I found such tales

suffocating,

excessively "Oriental," and even somewhat coarse. In those days, the

Thousand and One Nights seemed to pander too much to the tastes and

preferences

of the back streets. The crude, the two-faced, the evil (if they

weren't ugly

all along, they dramatized their moral depravity by becoming ugly) were

unremittingly repugnant, acting out their worst attributes over and

over, just

to keep the story going.

It could be

that my distaste upon reading the Thousand and One Nights for the

second time

arose from the puritanical streak that sometimes afflicts Westernizing

countries. In those days, young Turks like me who considered themselves

modern

viewed the classics of Eastern literature as one might a dark and

impenetrable

forest. Now I think that what we lacked was a key-a way into this

literature

that preserved the modern outlook but still allowed us to appreciate

the

arabesques, pleasantries, and random beauties.

II was only

when I read the Thousand and One Nights for the third time that I was

able to

warm to it. But this time I want to understand what it was that had so

fascinated Western writers through the ages – what had made the book

into a

classic. I saw it now as a great sea of stories-a sea with no end-and

what

astounded me was its ambition, its secret internal geometry. As before,

I

jumped from story to story, abandoning one midway if it started to bore

me and

moving to another. Though I had decided it wasn't a story's content

that

interested me so much as its shape, its proportions, its passions, in

the end

it was the stories' back-street flavor that most appealed to me-those

same evil

details I had once deplored. Perhaps with time I grew to accept that I

had

lived long enough to know that life is made of treachery and malice. So

on my

third reading, I was finally able to appreciate the Thousand and One

Nights as

a work of art, to enjoy its timeless games of logic, of disguises, of

hide-and-seek, and its many tales of imposture. In my novel The Black

Book, I

drew upon the magnificent story of Harun al Rashid, who goes out in

disguise

one night to watch his double, the false Harun al Rashid, impersonate

him; I

changed the story only to give it the feel of one of those

black-and-white

films of I940s Istanbul. With the help of commentaries and annotated

editions

in English, I was able, by the time I was in my mid-thirties, to read

the

Thousand and One Nights for its secret logic, its inside jokes, its

richness,

its beauties tame and strange, its ugly interludes, its impudences, and

its

vulgarities-it was, in short, a treasure chest. My earlier love-hate

relationship with the book no longer mattered: The child who could not

recognize his world in it was a child who had not yet accepted life as

it was,

and the same could be said of the angry adolescent who dismissed it as

vulgar.

For I have slowly come to see that unless we accept the Thousand and

One Nights

as it is, it will continue to be-like life, when we refuse to accept it

as it

is-a source of great unhappiness. Readers should approach the book

without hope

or prejudice and read it as they please, following their own whims,

their own

logic. Though perhaps I am already going too far-for it would be wrong

to send

a reader into this book with any preconceived ideas at all.

I would

still like to use this book to say something about reading and death.

There are

two things people always say about the Thousand and One Nights. One is

that no

one has ever managed to read the book from start to finish. The second

is that

anyone who does read it from start to finish is sure to die. Certainly

an alert

reader who has seen how these two warnings fit together will wish to

proceed

with caution. But there's no reason for fear. Because we're all going

to die

one day, whether we read the Thousand and One Nights or not.

A thousand

and one nights ...