|

Notes

1

|

Kỷ

niệm, kỷ niệm

Trong

số những đệ tử của

Faulkner, tệ nhất, [không có, để lận lưng, trên chuyến tầu suốt,

một cuốn

tiểu thuyết (1)], hẳn là Gấu, và, trong số những đệ tử làm dạng danh

Thầy,

hẳn có tay Llosa.

Gấu đã từng kể, trong những

ngày Mậu Thân, mỗi khi bí, mỗi khi bị những trái hoả tiễn VC làm "vãi

linh hồn", là lôi thầy ra, để chôm, một câu văn, một ý tưởng, làm mồi

nhử

những con chữ, từ xó xỉnh đâu đâu, mò về…

Llosa cũng có những

kỷ niệm y chang những ngày đầu đọc Faulkner.

(1) Một độc giả, và cũng là văn

hữu, đọc Gấu, phán, tất cả những truyện ngắn của Gấu, trên cái toàn thể

của nó,

có thể coi như là một truyện dài. Ý này, một nhà văn Miền Nam,

đã tử trận,

Doãn Dân, cũng đã nói ra, với một tay bạn thân của Gấu. Anh bạn cho Doãn Dân mượn đọc, cuốn Những

Ngày Ở Sài Gòn. Đọc xong, anh gật gù ra đòn:

1. Thời

gian viết, dàn trải, kéo dài cả một thời mới lớn. Trên cái nền đó, dư

sức nối kết thành

một cuốn tiểu thuyết.

Thưở con nít, ở Hà Nội. Rồi di cư, rồi lớn lên ở Sài Gòn, nhưng lúc nào

cũng hướng về Hà Nội, và rồi gặp lại nó, trong BHD, rồi bị thằng bố Bắc

Kít của BHD cấm cửa, rồi hai đứa rủ nhau vô Chợ Lớn rung răng rung rẻ,

rồi ông bố bắt tại trận....

2. Tay “NQT” này, là một gã quá

nhát, và rất sợ “hạnh phúc”, đến nỗi, giả như có được, thì cũng nghĩ

phận mình

“hèn mọn, không xứng đáng

với nó”!

Và anh ta dẫn câu của BHD:

Ta

cấm mi không bao giờ được nói, mi không xứng đáng xách dép suốt đời cho

ta!

-

Nadine

Sautel. La Fête au Bouc fait penser à la fois

à

une fugue à trois voix, à un film de Costa Gavras mâtiné de David

Lynch, et aux

romans de Faulkner, dont Mallraux disait qu'il abordait le thème de la

condition humaine comme « l'intrusion de la tragédie grecque dans le

roman

policier " ...

- Mario Vargas Llosa. J'aime

beaucoup votre idée de roman faulknérien. Faulkner est le premier écrivain

que

j'ai lu avec un crayon et un bout de papier à la main, essayant de

déchiffrer

ses structures temporelles, la façon dont il organisait les points de

vue.

Tragédie grecque? Roman policier? Certainement ! Les faits dépassaient

en

horreur l'imaginable, et il fallait les débusquer. Ça peut choquer

qu'on fasse

de la douleur ou de l'atrocité une matière pour la création. Mais c'est

la

condition de l'écrivain, de convertir ce qu'il lit, ce qu'il vit, en

œuvre

d'art. Et la dictature, Mallraux l'a bien montré, est un thème

particulièrement

riche, parce que c'est une expérience-limite qui oblige à affronter la

peur.

C'est l'épreuve dans laquelle on peut observer ce qu'il y a de meilleur

et ce

qu'il y a de pire dans l'être humain. Et la dictature de Trujillo, quand

j'étais jeune, était

considérée comme la forme emblématique de la dictature en Amérique

latine. Elle

en avait poussé à l'extême les caractéristiques: la cruauté, la

corrruption,

mais aussi la théâtralité. Trujillo

était insurpassable dans le grotesque: nommer colonel son fils Ramfis à

neuf

ans, puis général à douze ans, dans une cérémonie publique à laquelle

assistaient

tous les ambassadeurs ... Il dessinait luimême ses uniformes

extraodinaires, et

la forme de sa moustache hitlérienne, aidé par un top model newyorkais

qu'il

avait adopté. C'était à la fois son chef de protocole et son ministre

des

plaisirs. Je l'appelle Manuel Alfonso. J'ai gardé ces images. A

l'époque

j'étais étudiant en lettres à l'université San Marrcos, à Lima.

*

Llosa trả lời tờ Le Magazine Littéraire

Note: Bài phỏng vấn

này thật

tuyệt, và thật có ích cho đám nhà văn VC, Yankee mũi tẹt!

Tin Văn sẽ cố gắng dịch để gửi cho những bạn văn VC, vốn chỉ khoái

viết, đọc và dịch

thứ văn chương vô ích, vô hại, hay quá đát!

Bạn

biết đấy, với

tôi, viết là

một “lý do đủ”, để sống. Nó cứu tôi khỏi tình trạng tuyệt vọng tuyệt

đối, và sự

tuyệt vọng tuyệt đối gây bại liệt. Nhà văn không được xấu hổ về cái

chuyện “đâm

xầm vào chính trị” [“từ” của một đấng bạn quí của Gấu]. Nhà văn phải có

trách

nhiệm, do quyền năng của những chữ của người đó, lên những độc giả của

mình. Tôi

luôn trung thành với Sartre, cho tới khi ông ta phán một câu thật khó

nghe với

tờ Le

Monde, vào

năm 1964 [“Đứng trước

một đứa trẻ đang chết, cuốn Buồn Nôn chẳng

là cái đéo gì!]. (1) Vào cái lúc mà người ta thay thế

lý trí bằng những hành động của niềm tin, [đây là quan điểm của tôi về

ý thức hệ],

nhà văn là kẻ chứng tỏ cái thực, một cách thuần lý. Điều này thật quan

trọng, là

vì, một khi mà con người xử sự một cách phi lý, thì đó là lúc bạo lực

xuất hiện.

Điều quan trọng với nhà văn là phải một lòng một dạ, chân thực, với

chính mình,

và sống với tất cả sự toàn vẹn khả hữu, điều mà anh ta viết. Tôi, tôi

cần phải

thò cái chân của mình xuống đường phố, ngọ ngoạy trong cái gì đang xẩy

ra, đang

thành hình.

(1) Cái tật ưa xổ nho này, Gấu học ở CM, một cô bạn. Sorry abt that. NQT

carnets de lecture

par Enrique Vila-Matas

INTERVIEWS INVENTÉES

propos

imaginaires de Marion Brando, Noureïev, Anthony Burgess ...

Comme disait

Barthes, la fortune que connaissent les interviews de nos jours est

surtout due

à des raisons économiques. Quand il s'agit, par exemple, d'un écrivain,

l'interview est un article rémunéré: «Vous n'avez pas le temps de nous

rédiger

un texte? Accordez- nous donc une interview! » Dans l'interview,

l'interviewé

travaille gratuitement et l'intervieweur en tire les bénéfices

économiques. Il

est vrai que les interviewés sont des saints.

Cela dit, je dois dire que

j'étais dans ma jeunesse d'une extrême cruauté car, pour gagner ma vie,

je

faisais des interrviews, j'importunais de pauvres gens qui, répondant à

mes

questions, me donnaient à manger. Certains de mes interrviewés furent

doublement mes victimes. Je vais m'expliquer. Non seulement je les

importunais

et leur faisais perdre leur temps avec mes interviews, mais en plus,

j'inventais cerrtaines d'entre elles. Tout commença quand, peu après

avoir

déniché à la rédaction du magazine

Fotogramas le premier travail de ma vie, on

me chargea de traduire à toute vitesse de l'anglais une interview

exclusive de

Marlon Brando par Julie Gilmore. Comme je ne comprenais pas un mot

d'anglais et

craignais qu'on ne me renvoie, j'inventai tout de A à Z- je faisais

dire à

l'acteur de solennelles sottises -, et elle fut publiée telle quelle,

sans que

personne se rende compte qu'elle était fausse. Vu le succès de la

friponnerie,

je ne tarrdai pas à inventer une autre interview. Le danseur Noureïev

passa par

Barcelone et je pris un rendez-vous pour l'interviewer dans son hôtel,

un jeudi

matin. Le mercredi soir, je tombai par hazard sur lui dans une

discothèque et

un absurde incident au compptoir de la boîte fit que nous nous

disputâmes.

Naturelleement,le lendemain matin, je n'osai pas me rendre à l'hôtel

avec mon

œil au beurre noir et lui dire que j'étais l'intervieweur qu'il

attendait, si

bien que je décidai - après tout, j'étais déjà expert en la matière -

d'inventer l'interrview. Je fis dire à Noureïev des horreurs

historiques sur le

ballet et les corridas.

Les jours suivants, je fus

entraîné dans un tourbillon d'interviews inventées. On me demanda d'en

faire

une avec Anthony Burgess et je me

rendis au rendez-vous avec le texte déjà écrit: un puzzle d'interviews

précédentes, accordées par Burgess lui-même. Cinq minutes avant que je

ne

commence à formuler mes questions, Burgess, voyant que je ne notais

rien, me

demanda, logiquement inquiet, pourquoi je l'écoutais sans magnétophone,

bras

croisés. Je lui expliquai, sans broncher, que, comme la rédaction

voulait que

je lui remette au plus vite mon travail, j'avais décidé de l'écrire à

l'avance.

Je craignais le pire et ce fut le contraire qui se passa: l'auteur

d'Orange

mécanique sourit, m'offrit un whisky et me dit qu'à Ceylan, lorsqu'il

était

jeune et jourrnaliste, il avait, lui aussi, inventé beaucoup

d'interviews.

Ce fut un tel encouragement

que, quinze jours plus tard, interviewant dans ce même hôtel Patricia

Highsmith, j'étais parfaitement serein, même si, comme à son habitude,

ses

réponses étaient d'une sobriété étonnante, presque toutes

monosyllabiques.

Personne, sauf son amie Noëlle Loriot, n'avait réussi à faire une

bonne, très

bonne interview avec elle: une interview pour un magazine français au

cours de

laquelle, pour la première et dernière fois, elle révéla des choses

intimes,

une grande interview. Après avoir interrogé patiemment Highsmith et

achoppé sur

sa sobriété, de retour à la maison, je recopiai intégralement

l'interview de

Noëlle Loriot et décidai de ne plus y revenir: elle fut publiée et ce

fut mon

premier grand succès dans le monde du journalisme. Je fus promu aux

articles

d'humeur et laissai dans mon sillage l'époque des interviews inventées,

après

avoir eu toutefois le temps d'en faire une - terrible - avec Cornelius

Castoriadis. Et une autre avec Tony Curtis. Les effets négatifs?

Aujourd'hui,

sachant qu'il ne serait guère éthique que je proteste, des jeunes gens

de

partout inventent impunément des interviews avec moi qui rivalisent en

ridicule

ou en excentricité. Ce qui veut dire, comme s'il s'agissait d'une

fatalité bien

mériitée, que, ces dernières années, je dis, partout en ce bas monde,

toutes

sortes de sottises .•

Traduit de l'espagnol par André Gabastou

Bài viết tuyệt vời,

làm Gấu nhớ tới, lần ngồi Quán Chùa với ông anh, và

ông rất khoái ba cái vụ phỏng vấn tưởng tượng, và, sau này, Gấu

cũng đã tự phỏng vấn Gấu, và mở hẳn một chương, [nghề

riêng ăn đứt hồ cầm một chương] trên Tin Văn, Phỏng

vấn dởm, nhưng dởm quá, đi

chưa được

một đường, thì đã tắc tị!

Vì sao

bác viết

tiếng Việt

kiểu Tây vậy?

*

Hỗn,

hách, phách lối, là Nabokov,

qua

Bạo Miệng. Nhưng

cũng thật xác đáng, là những nhận xét của ông.

Làm

Gấu nhớ đến… Gấu!

Chứng

cớ, chỉ nội câu phán nhỏ

nhẹ, NS là nhà văn dễ dãi và hạnh phúc, là đủ để ông nhà thơ kiêm thầy

giáo ‘anh

thay mực cho vừa mầu áo tím’ nhớ đến tận già!

Nhờ

vậy mà Gấu có

nick thật là tuyệt vời là "tên sa đích văn nghệ"!

Khi

ra hải ngoại, nhớ đến nick của mình, Gấu đã tự nhủ lòng, bye bye

cái nghề khốn nạn phê bình, điểm sách, chính vì thế mà một nhà văn ra

đi từ Miền Bắc, nhận xét, chú viết thật hiền, khác hẳn "mấy ông kia",

nhưng, cuối cùng, bị chúng chọc giận, chịu không thấu, bèn tái xuất

giang hồ!

Hà,

hà!

*

-

Gogol?

-

J'ai pris grand soin à ne

rien apprendre de lui. En tant que maître, c'est un écrivain dangereux

et

traître. A son niveau le plus bas, comme dans ses machins ukrainiens,

il est un

écrivain sans valeur; à son niveau le plus haut, il est incomparable et

inimitable.

[-Gogol?

Tôi

cẩn trọng chính tôi, đừng

bao giờ học, bất cứ cái chó gì từ thằng cha này. Như là một bậc

thầy, thì ông ta là một nhà văn

nguy hiểm và phản phúc. Ở cái mức tệ hại, ông ta là một anh Cu Sài

Ukranien vứt đi,

ở cái mức đỉnh cao, không ai so được với ông ta, và chẳng ai bắt chước

được ông.]

Nhắc

tới Gogol nhân mới đọc một bài viết trên TLS, thật tuyệt vời, về cuốn Những Linh Hồn Chết, bản dịch mới

nhất, có kèm theo minh họa của Chagall, trước khi ông này vĩnh viễn rời

bỏ nước Nga.

Bài điểm so sánh mối lương duyên lạ lùng giữa minh họa và tiểu thuyết:

Chagall minh họa Dead Souls như một món quà vĩnh biệt Nga xô, đi, tái

định cư nơi xứ trời Tây phương, và không bao giờ trở lại Nga xô nữa.

Gogol viết Dead Souls ở ngoài nước Nga, và khi trở về, không thể nào

tái định cư ở trên quê hương Nga xô của ông.

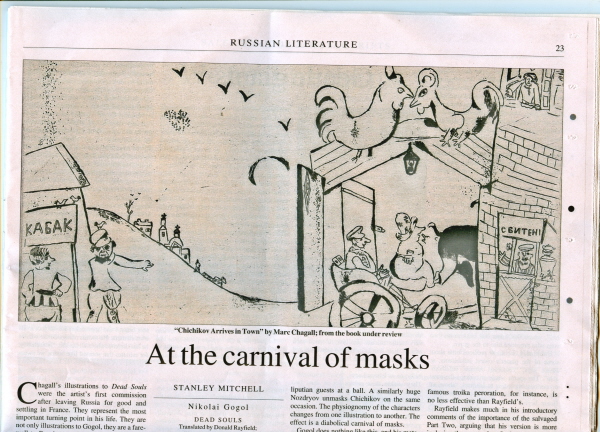

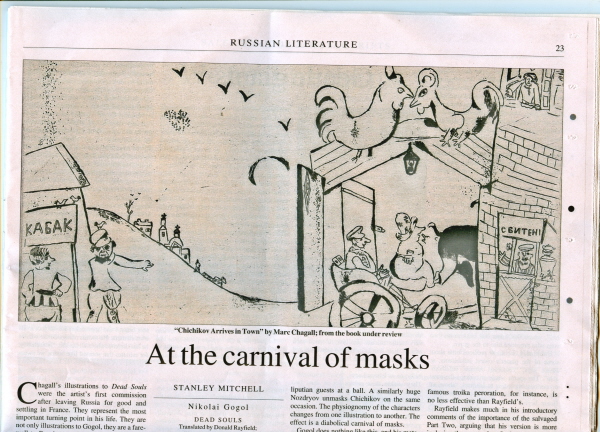

STANLEY MITCHELL

Nikolai Gogol

DEAD SOULS

Translated by

Donald Rayfield; illustrated by Marc Chagall 366pp.

Garnett Press. £29.99.

978095358 787 8

Chagall's

illustrations to Dead Souls were the artist's

first

commission after leaving Russia

for good and settling in France.

They represent the most important turning point in his life. They are

not only

illustrations to Gogol, they are a farewell to Russia - to the Jewish shtetl and to Chagall's

brief political

service to the Bolsheviks in the new Art Academy of his native Vitebsk.

The

etchings are often extraordinarily grotesque and belong to a turbulent

stream

of grotesque art in the early years of the Revolution. Bely, Bulgakov

and Babel were among the

writers of the

time who felt a

particular kinship with Gogol, and had Chagall remained in Russia

he might

well have become the artist of Meyerhold's scandalous production of

Gogol's Inspector

General in

1926. He had

already sketched figures for the play when Moscow's

Theatre of Revolutionary Satire visited Vitebsk.

So, too, with Gogol's other plays, The

Gambler and

The

Marriage;

and to

the same year belongs a watercolor, "In Honor of Gogol" (1919). The

Russian satirist was in his blood. There is also the coincidence that

Gogol

left Russia

for twelve years in order to write Dead

Souls.

This, too was a kind of farewell, for although Gogol

returned to his

homeland he was never able to settle there again. Shortly before his

death in Russia

in 1852,

he burned the drafts of the second part of his masterpiece; only

fragments have

survived.

This

is

the first edition of Dead Souls to include all

Chagall's

illustrations since their original appearance in Paris in 1948. However

important the

etchings, they have remained the Cinderella of Chagall's work. His

dealer

Ambroise Vollard, who had commissioned him to illustrate the Fables of La Fontaine and

his sketches

for the Bible (sending him to Palestine

for the purpose), kept them in a cellar for twenty years. They were

published

by Tériade nine years after Vollard's death and were awarded a grand

prix at

the Venice

graphics biennale immediately afterwards. They have been routinely

ignored by

curators and scholars ever since.

The

illustrations marked a

new direction for Chagall. With the one exception, an earlier

experiment in

autobiography, he was etching for the first time, searching exuberantly

for new

techniques that ranged from drypoint to aquatint. To quote from Marx in

a

different context: all that is solid melts into air. When Chichikov

visits the

landowner, Manilov, the two men are done in aquatint and look

relatively human.

When they part, their bodies become transparent, as if they are

themselves the

dead souls. Magnitudes vary crazily and the humor is magnificent. A

monstrous

Sobakevich prepares to settle into a diminutive armchair. The clerks in

the

court office are reduced to tiny heads, wielding matchstick pens at

barely

visible desks, or faces floating in a void. A giant condescending

Chichikov

appears before the Lilliputian guests at a ball. A similarly huge

Nozdryov unmasks

Chichikov on the same occasion. The physiognomy of the characters

changes from

one illustration to another. The effect is a diabolical carnival of

masks.

Gogol does nothing like this, and his metaphorical flights are by

comparison

realistic. For this reason, a commentary on the relationship of the

images to

the text would have been welcome. Gogol himself refused any request to

illustrate

his work, commenting that any illustration could only "sweeten" the

novel.

In his short introduction, Donald Rayfield claims that Gogol found in

Chagall

his true illustrator, calling Chagall's imagination "surreal". Yet in

his comments on the novel, Rayfield sides with the nineteenth-century

"realist"

interpretations. Gogol's characters, he suggests, are alive and well in

today's Russia.

All the more reason, then, to shed some light on the notable

nineteenth-century

illustrators of Dead Souls, Alexander

Agin and Pyotr Boklevsky. Boklevsky's portraits of Sobakevich and the

miser,

Plyushkin, are marvellous satires in the spirit of the writer Mikhail

Saltykov-Shchedrin.

Chagall's Plyushkin is very similar to Boklevsky's. Rayfield

accompanies the

etchings with a new translation which has a twofold aim: to correct the

mistakes

of previous translators and to make the novel sound like a theatrical

text in

which even the longest sentences (and there are many) can be read out

loud

without loss of breath. Certainly, he succeeds with his first aim, and

his

translation is fresher and more energetic than the best previous

version, by

David Magarshack (1961). In other respects it is not a marked

improvement. Magarshack's

rendering of Gogol's famous troika peroration, for instance, is no less

effective than Rayfield's.

Rayfield

makes much in his

introductory comments of the importance of the salvaged Part Two,

arguing that

his version is mort inclusive than any other. In fact, Christophel

English's

translation (1987) includes both the stories that Rayfield misses in

earlier

translations. More importantly, Rayfield suggest that Part Two

prefigures the

novels of Goncharov, Turgenev, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. Since Part Two

sets out

on the road of redemption, where we behold a freshly burnished

Chichikov,

accompanied by figures who on the whole are less imaginative than those

in Part

One, we are unlikely to find the future Russian literature germinating

here.

Nor can I imagine Chagall wanting to illustrate Part Two. Nikolai

Dobrolyubov

spotted the only convincing connection between Part Two and later

Russian

fiction in his essay What is Oblomovvism?

(1859-60), where he linked the landowners Tentetnikov and Platonov with

Gonchaarov's hero, Oblomov. But in Part One, Gogol had already

characterized an

idle dreamer in Manilov who is much more perniciously comic than this

pair. The

famous remark often attributed to Dostoevsky that "We all emerged from

Gogol's overcoat" (a reference to Gogol's story of 1842) remains more

accurate.

TLS

JULY 10 2009

Cùng

số báo, có bài điểm

Những đứa

trẻ của Dr. Zhivago: Giới trí thức

sau cùng của Nga xô, trong bài điểm, có

một nhận xét thật tuyệt

vời về

đám trí thức "sau cùng" này: "Nếu hệ thống Xô Viết của chúng tớ không

sụp

đổ một cách hòa bường, thì một Thế Chiến Thứ Ba không thể nào tránh

được, và hãy thử tưởng ra những nỗi ghê rợn của nó."

Nhưng,

bởi vì Liên Xô sụp đổ mà mới có hai cuộc chiến của

me-xừ Bụi Cây, và Cuộc Đại Suy Thoái hiện nay! NQT

Vì sao

bác viết

tiếng Việt

kiểu Tây vậy?

Gấu

đọc Tô Hoài rất sớm, và

giấc

mộng, sẽ có ngày tới được nước Nam Kỳ, là do đọc ông mà có.

Khi còn ở xứ Bắc, mỗi

lần đói,

mỗi lần rét, mỗi lần ăn miếng ăn, ăn thêm một câu nói, là giấc mơ sẽ có

ngày tới được nước Nam Kỳ lại trỗi dậy.

Cho tới khi tới được

nước Nam

Kỳ.

Tưởng thoả mãn, mà

thoả mãn

thực, nhưng, oái oăm thay, một nước Nam Kỳ khác xuất hiện!

Lúc thì ở nơi BHD, và

cái nước

Nam Kỳ lần này, khốn nạn thay, lại chính là cái xứ Bắc Kỳ mà Gấu đã bỏ

chạy!

Và ở trong bao nhiêu

nước Nam Kỳ khác,

do đọc sách mà có!

Trong những “nước Nam Kỳ” do đọc

sách những ngày mới lớn mà có đó, có “Sa mạc Tartares” của Dino Buzzati.

Mới đây, đọc A

Reading Diary,

Alberto Manguel có viết về cuốn này, ông nói là đọc nó vào thời mới

lớn, cũng

như Gấu, đọc nó vào lúc mới lớn, tại nưóc Nam Kỳ, tại Sài Gòn, khi có

BHD.

*

Gấu mua cuốn A Reading Diary

Nhật Ký Đọc, cũng lâu rồi. Quăng vào một xó, rồi quên luôn, cho tới khi

dọn nhà, nhặt nó lên…

Buzzati notes that,

from the

very beginning of his writing career, people heard Kafka's echoes in

his work.

As a consequence, he said, he felt not an inferiority complex but "an

annoyance complex." And as a result, he lost any desire to read Kafka's

work

Buzzati and Kafka:

Perhaps it is not only impossible to achieve justice. Perhaps we have

even made

it impossible for a just man to persevere in seeking justice.

Buzzati cho biết, vào lúc khởi nghiệp, người ta nói, có mùi Kafka ở

trong những gì ông viết ra. Nghe vậy, ông cảm thấy, không phải mặc cảm

tự ti, mà là bực bội. Và sau cùng, ông mất cái thú đọc Kafka!

Buzzati và Kafka:

Có lẽ không phải chỉ là bất khả, cái chuyện đi tìm công lý.

Nhưng bất khả còn là vì: Chúng ta làm cho nó trở thành bất khả, để chỉ

cho có một thằng cha, cố đấm ăn sôi, cứ đâm sầm vào cái chuyện tìm công

lý!

"Không con, thì ai bi giờ hả mẹ?"

[Gửi NTT. NQT]

Gấu đọc Sa mạc Tác Ta [Tartar là một giống dân], bản tiếng Pháp, và

không hiểu làm sao, bị nó ám ảnh hoài, câu chuyện một anh sĩ quan, ra

trường, được phái tới một đồn biên xa lắc, phòng ngừa sự tấn công của

dân Tác Ta từ phía sa mạc phía trước. Chờ hoài chờ huỷ, tới khi già

khụ, ốm yếu, hom hem, sắp đi, thì nghe tin cuộc tấn công sắp sửa xẩy

ra....

Đúng cái air Kafka!

Trên tờ Bách Khoa ngày nào còn Sài Gòn có đăng truyện ngắn K. của

Buzatti. Đây là câu chuyện một anh chàng, sinh ra là bị lời nguyền,

đừng đi biển, đi biển là sẽ gặp con quái vật K, nó chỉ chờ gặp mày để

ăn thịt. Thế là anh chàng chẳng bao giờ dám đi biển, cho đến khi già

cằn, sắp đi, bèn tự bảo mình, giờ này mà còn sợ gì nữa.

Thế là bèn ra Vũng Tầu, thuê thuyền đi một tua, và quả là gặp con K

thật. Con quái vật cũng già khòm, sắp đi, nó thều thào bảo, tao có viên

ngọc ước quí, chờ gặp mày để trao, nó đây này...

Ui chao Gấu lại nhớ đến Big Minh, thều thào, tao chờ chúng mày để bàn

giao viên ngọc quí Miền Nam, và con K bèn biểu, tao lấy rồi, cám ơn

lòng tốt của mày!

Doãn Quốc Sĩ, có chuyện Sợ Lửa, tương tự. Đây là câu chuyện một anh

chàng sinh ra đời là bị thầy bói nguyền chớ có đến gần lửa. Thế rồi,

một ngày đẹp trời, thèm lửa quá, bèn đến gần nó, và ngộ ra một điều,

sao mà nó đẹp đến như thế.

Thế là về, và chết!

Gấu cũng thấy lửa rồi. Và đang sửa soạn về...

Sự thực, Gấu

không gặp lửa, mà

gặp… xác của Gấu, trôi lều bều trên dòng Mékong, lần tá túc chùa Long

Vân,

Parksé, chờ vuợt sông qua trại tị nạn Thái Lan. Gấu đã kể chuyện này

nhiều lần

rồi.

C'est à

Paris, à la fin de 1939 ou au début de

1940, alors que j'étais terrassé par une attaque de névralgie

intercostale, que

je sentis la première petite palpitation de Lolita. Autant qu'il m'en

souvienne, ce frisson avant-coureur fut déclenché, je ne sais trop

comment, par

la lecture d'un article de journal relatant qu'un savant avait réussi,

après des

mois d'efforts, à faire esquisser un dessin par un grand singe du

Jardin des

Plantes; ce fusain, le premier qui eût été exécuté par un animal,

représentait

les barreaux de la cage de la pauvre bête.

Nabokov: A PROPOS DE «

LOLITA

»

*

1989. Trong một bài viết ở

phía sau tác phẩm, Nabokov kể lại, phút hạnh ngộ giữa ông và cô bé kiều

diễm,

thời gian ông bị những cơn đau đầu thường trực hành hạ. Và một thoáng

nàng - la

palpitation de Lolita - đã lung linh xuất hiện, khi ông đang đọc mẩu

báo, thuật

câu chuyện về một nhà bác học đã thành công trong việc dậy vẽ cho một

chú khỉ ở

một vườn thú. "Tác phẩm đầu tay" của "con vật đáng thương"

là hình ảnh mấy chấn song của cái chuồng giam giữ nó.

Trong chuyến đi dài chạy trốn

quê hương, trong mớ sách vở vội vã mang theo, tôi thấy hai cuốn, một

của

Nabokov, và một của Koestler. Tôi đã đọc Darkness at Noon" qua bản dịch

"Đêm hay Ngày" do Phòng Thông Tin Hoa Kỳ xuất bản cùng một thời với

những cuốn như "Tôi chọn Tự do"... Chúng vô tình đánh dấu cuộc di cư

vĩ đại với gần một triệu người, trong có một chú nhỏ không làm sao quên

nổi

chiếc chuồng giam giữ thời ấu thơ của mình: Miền Bắc, Hà-nội.

Lần thứ nhì bỏ chạy quê

hương, cùng nỗi nhớ Sài-gòn là sự thật đắng cay mà tuổi già càng làm

thêm cay

đắng: Một giấc mộng, dù lớn lao dù lý tưởng cỡ nào, cũng không làm sống

lại,

chỉ một sợi nắng Sài-gòn: Trong những đêm chập chờn mất ngủ, hồn thiêng

của thành

phố thức giấc ở trong tôi, tôi tưởng hồn ma của chính mình đang lang

thang trên

những nẻo đường xưa cũ, sống lại cái phần đời đã chết theo cùng với Sài

Gòn,

bởi cái phần đời đó mới đáng kể. Tôi đọc lại Nabokov và lần ra sợi dây

máu mủ,

ruột thịt giữa tác giả-nhà văn lưu vong-con vật đáng thương-nàng

nymphette tinh

quái. Đọc Koestler để hiểu rằng, tuổi trẻ của tôi và của bao lớp trẻ

sau này,

đều bị trù yểm, bởi một ngày mai có riêng một con quỷ của chính nó:

Miền Bắc,

Hà-nội.

Lần

Cuối Sài Gòn

Như vậy, BHD thoát ra từ cái

bóng của Lolita, và cả hai thoát ra từ bóng của một con khỉ ở nơi

chuồng thú, đằng

sau tất cả, là cái chuồng giam giữ tuổi thơ của cả hai [của Gấu và

BHD]: Miền Bắc.

Hà Nội.

Gấu đọc những dòng trên,

trong trại tị nạn, cùng lúc viết Lần Cuối Sài Gòn. Lần đầu tiên xuất

hiện trên

báo Làng Văn, Canada. Báo về tới trại, 'gây chấn động' trong đám người

tị

nạn. Bây

giờ, nhớ lại, vẫn còn cảm thấy bồi hồi xúc động. Nhưng phần hồn của

Gấu, để lại

Trại, phải là

Bụi.

CHÙA

SIKIEW Khu C

"Nhưng nếu không vì dung nhan

tàn tạ,

chắc gì Thầy đã nhận ra em?"

Sikiew nổi tiếng trong đám người tị nạn vì bụi của nó.

Ngay những giấc mơ của họ cũng đầy bụi.

|

|