|

Notes

1

|

Thiên An Môn 20 năm

sau

Tiananmen Ghosts.

Twenty

years after China's

tragedy, a secret journal reveals new details of the power struggle

that led to

the massacre

BY

ADI IGNATIUS

WHEN

THE TANKS AND troops

blasted their way into Beijing's Tiananmen Square 20 years ago,

crushing the

student-led protest movement that had captivated the world, the biggest

political casualty was Chinese Communist Party chief Zhao Ziyang, the

man who

had tried hardest to avoid the bloodshed.

Outmaneuvered

by his

hard-line rivals, Zhao was stripped of power and placed under house

arrest. The

daring innovator who had introduced capitalist policies to post-Mao

Zedong

China spent his last r6 years virtually imprisoned, rarely allowed to

venture

away from his home on a quiet alley in Beijing. As his hair turned

white, Zhao

passed many lonely hours driving golf balls into a net in his courtyard.

Yet

as it turns out, Zhao

never stopped thinking about Tiananmen. Through courage and subterfuge,

he

found a way, in the isolation of his heavily monitored home, to

secretly record

his account of what it was like to serve at China's

highest levels of power-and

more amazingly, he sneaked his memoir out of the country. Published

this month,

Prisoner of the State: The Secret Journal of Premier Zhao Ziyang

provides an intimate

look at one of the world's most opaque regimes during some of modern China's

most

critical moments. It marks the first time a Chinese leader of such

stature-as

head of the party, Zhao was nominally China's highest-ranking

official-has spoken frankly about life at the top. Most significantly,

Zhao's

account could encourage future Chinese leaders to revisit the events of

Tiananmen

and acknowledge the government's tragic mistakes there. Hundreds of

people were

killed or imprisoned by government forces, though few Chinese

today know the full story.

In

the book, Zhao, who died

in 2005, details the drama and conflict behind the scenes during the

Tiananmen protests.

The priority of the party's leaders ultimately wasn't to suppress a

rebellion

but to settle a power struggle between conservative and liberal

factions. China's

hard-liners had tried for years to derail the economic and political

innovations that Zhao had introduced; Tiananmen, Zhao demonstrates in

his

journal, gave the conservatives a pretext to set the clock back. The

key moment

in Zhao's narrative is a meeting held at Deng Xiaoping's home on May

17, 1989,

less than three weeks before the Tiananmen massacre. Zhao

argued that the government should back

off from its harsh threats against the protesters and look for ways to

ease

tensions. Two conservative officials immediately stood up to criticize

Zhao,

effectively blaming the escalating protests on him. Deng had the last

word with

his fateful decision to impose martial law and move troops into the

capital. In

a rare historical instance of a split at the party's highest levels,

Zhao

wouldn't sign on: "I refused to become the General Secretary who

mobilized

the military to crack down on students."

With

his political career

more or less finished, Zhao went to Tiananmen

Square

to talk to some of the tens of thousands of protesters massed there.

Premier Li

Peng, Zhao's primary rival, tagged along-though Zhao says Li was

"terrified"

and quickly left the scene. A teary Zhao spoke to student leaders

through a bullhorn. "We have

come too late," he said, urging students to leave the square to help

calm

things down. Few heeded his words. About two weeks later, the tanks and

troops

were sent in.

When

the assault on

Tiananmen

began, he could only wince as he heard the pop-pap-pop of automatic

rifles near

his home: "While sitting in the courtyard with my family, I heard

intense

gunfire," he wrote. "A tragedy to shock the world had not been

averted, and was happening after all."

Zhao's

effort to record and

preserve his memoir required both secrecy and conspiracy. Under the

noses of

his captors, he recorded his material on about 30 tapes, each roughly

an hour

long. Judging from the content, most of the recording took place in or

around

2000. Members of his family say even they were unaware that this was

taking

place. The recordings were on cassettes-mostly Peking

opera and kids' music-that had been lying around the house. Zhao

methodically

noted their order by numbering them with faint pencil marks. There were

no

titles or other notes. The first few recordings were of discussions

with

friends. But most were taped alone, and Zhao apparently read from a

text he had

prepared.

When

Zhao had finished the

taping after a couple of years, he found a way to pass the material to

a few

trusted friends who had also been high-level party officials. Each was

given

only some of the recordings, evidently to hedge against their being

lost or

confiscated. After Zhao died four years ago, some of the people who

knew about

the recordings-they can't be named here because of fears of retaliation

from

Chinese authorities-launched a complex, clandestine effort to gather

the

material in one place and transcribe it for publication. Later, another

set of

tapes, perhaps the originals, was found hidden among his

grandchildren's toys

in his study.

The

power structure described

in the book is chaotic and often bumbling. In Zhao's narrative, Deng is

a

conflicted figure who urges Zhao to push hard for economic change but

demands a

crackdown on anything that seems to challenge the party's authority.

Deng is at

times portrayed not as an emperor but as a puppet subject to

manipulation by

Zhao or his rivals, depending on who presents his case to the old man

first.

Once

placed under house

arrest, Zhao could do little but obsess over past events, rewinding the

clock

to pore over the technicalities of the state's case against him. His

few

attempts to venture out met with almost comically Kafkaesque

resistance. For

example, when authorities finally permitted him to play pool at a club

for

party officials, they first swept the place of other people, ensuring

that Zhao

played alone. His captors ultimately succeeded in keeping him out of

view and

silencing his voice, and they put up enough obstacles to deter all but

the most

determined visitors. As he said in his recordings, "The entrance to my

home is a cold, desolate place."

Yet

inside the gate, Zhao was

busy at work, taping the journal that now gives him a final say about

what

really happened and what might have been. It's a fitting final act for

a man

who made enormous contributions to today's China. Although Deng

generally gets

credit for modernizing China's

economy, it was Zhao who brought about the innovations-from breaking up

Mao's

collective farms to creating free wheeling special economic zones along

the

coast-that jolted China's

economy from its slumber. And it was Zhao who had to continually

outflank powerful

rivals who didn't want to see the system change.

The

China that Zhao

describes is very much alive now. The country's team of leaders

continues to

promote economic freedom yet intimidates or arrests anyone who dares to

call

for political change.

At

the end of last year, more

than 300 Chinese activists, marking the 60th anniversary of the

Universal

Declaration of Human Rights, jointly signed Charter 08, a document that

calls

on the party to reform its political system and allow freedom of

expression. Beijing responded as it

often does: it interrogated many of the signatories and arrested some,

including prominent dissident Liu Xiaobo, who was active during the

Tiananmen

protests.

At

the end of his journal,

Zhao concludes that China

must become a parliamentary democracy to meet the challenges of the

modern

world-a remarkable observation from someone who spent his entire career

in

service to the Communist Party, and one that might well provoke a

debate on China's

Internet discussion boards and in its chat rooms. Zhao's ultimate aim

was a

strong economy, but he had become convinced that this goal was

inextricably

linked to the development of democracy. China's ability to avoid

another

tragedy like Tiananmen might depend on how quickly that comes about. •

TIME

May 25, 2009

Ignatius

is the editor of Harvard Business

Review and

one of the editors of Prisoner of

the State

*

Bài trên Paris

Match

cho

thấy, không một sinh viên nào nghĩ quân đội sẽ bắn vào đám đông, xe

tăng sẽ nghiền nát cuộc biểu tình.

Họ

chỉ nghĩ, cùng lắm là bị bắt, bị bỏ bóp, rồi cho về, và đa số mang

theo lương thực, đủ dùng trong 10 ngày, ngây thơ y chang đám sĩ quan

Ngụy!

Zhao's ultimate

aim was a strong economy, but he had become convinced that this goal

was

inextricably linked to the development of democracy. China's

ability to avoid another tragedy like Tiananmen might depend on how

quickly

that comes about. •

Mục tiêu tối hậu

của Zhao là một nền kinh tế mạnh, nhưng ông tin rằng, nó gắn chặt với

sự phát

triển dân chủ. Khó mà tránh một cú Thiên An Môn trong tương lai, nếu

‘nhất bên

trọng nhất bên khinh’!

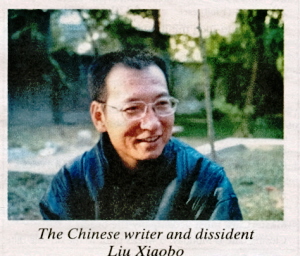

THE POET IN

AN UNKNOWN PRISON

Thi

sĩ trong nhà tù không ai biết

On April 16,

the PEN American Center named the Beijing-based writer and dissident

Liu Xiaobo

the recipient of the 2009 PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award.

The

award honors international literary figures who have been persecuted or

imprisoned

for exercising or defending the right to freedom of expression.

Liu is a

literary critic, activist, and poet who participated in the

prodemocracy

movement in China in the spring of 1989. After the Tiananmen crackdown

he spent

two years in prison, and since then has been often harassed by the

police and

imprisoned several times for his political activism and writing. On

December 8,

2008, he was arrested for signing Charter 08, a declaration calling for

democracy, human rights, and an end to one-party rule in China, which

has now

been signed by over 8,500 people throughout the country. * Since his

arrest Liu

has been held without charges or trial at an unknown location in

Beijing.

*****

* See

www.nybooks.com for a translation of Charter 08, together with a

postscript by

Perry Link ["China's Charter 08," NYR, January 15]; and for remarks

by Vaclav Havel on presenting the Homo Homini Award to Liu and other

signers of

Charter 08 in Prague, as well as the text of speeches given by two of

the

signers of Charter 08 at the award ceremony.

The

following remarks were sent to PEN by Liu's wife, Liu Xia, and read at

the

award ceremony in New York on April 28.

-

The

Editors

Ladies

and

Gentlemen,

It is a pity

that both my husband Liu Xiaobo and I could not be present this evening

to

receive this award.

Twenty-six

years ago, both of us were writing modern poetry. It is through our

poetry that

we became acquainted and eventually fell in love. Six years later, the

unprecedented student democratic movement and massacre occurred in

Beijing.

Xiaobo dutifully stood his ground and, consequently, became widely

known as one

of the so-called June 4 "black hands." His life then changed forever.

He has been put into jail several times, and even when he is at home,

he is

still, for the most part, not a free man. As his wife, I have no other

choice

but to become a part of his unfortunate life.

Yet I am not

a vassal of Liu Xiaobo. I am very fond of poetry and painting, but at

the same

time, I have not come to view Xiaobo as a political figure. In my eyes,

he has

always been and will always be an awkward and diligent poet. Even in

prison, he

has continued to write his poems. When the warden took away his paper

and pen,

he simply pulled his verse out of thin air. Over the past twenty years,

Xiaobo

and I have accumulated hundreds of such poems, which were born of the

conversations between our souls. I would like to quote one here:

Before you

enter the grave

Don't forget

to write me with your ashes

Do not

forget to leave your

address in

the nether world (1)

Another

Chinese poet, Liao Yiwu, has commented on Xiaobo's poem: "He

carries the burden of those who died on June 4 in his love, in his

hatred, and

in his prayers. Such poems could have been written in the Nazis'

concentration

camps or by the Decembrists in Imperial Russia. Which brings to mind

the famous

sentence: 'It is barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz.''' Such

statements

are also characteristic of the situation in China after 1989.

I

understand, however, that this award is not meant to encourage Liu’s

Xiaobo the

poet, but rather to encourage Liu Xiaobo the political commentator and

initiator of Charter 08. I would like to remind everyone of the close

connection between these two identities. I feel that Xiaobo is using

his

intensity and passion as a poet to push the

democracy movement forward in China. He shouts passionately as a poet

"no,

no, no" to the dictators.

In private,

he whispers gently to the dead souls of June 4, who, to this day, have

not

received justice, as well as to me and to all his dear friends: "yes,

yes."

Finally, I

extend my deepest gratitude to the PEN American Center, the Independent

Chinese

PEN Center, and everyone in attendance at this event tonight.

Liu Xia,

April 17, 2009,

at my not-free home in

Beijing

(translated

from the Chinese by Liao Tienchi)

NYRB

May 28, 2009

(1)

Truớc

khi bước

xuống huyệt

Nhớ viết cho

tớ

Bằng tro cốt

của bạn

Đừng

quên

ghi địa chỉ của bạn

Ở

phía bên

cánh cửa (2)

(2)

Hãy

mở giùm

ta cánh cửa này, Gấu đập và khóc ròng!

Ouvrez-moi

cette porte où je frappe en pleurant.

Apollinaire

Vĩnh Biệt

*

Mấy câu thơ

trên làm Gấu nhớ tới câu trả lời của tay blogger Perez Hilton, trên Time, June 8, 2009: Nếu

may mắn, tôi sẽ tìm ra cách để tiếp tục viết blog, từ phía bên kia nấm

mồ.

Cùng

số báo,

có bài viết, liệu cái đói có làm ngỏm nghệ thuật? Curtains: Can The

Arts Survive

The Recession?

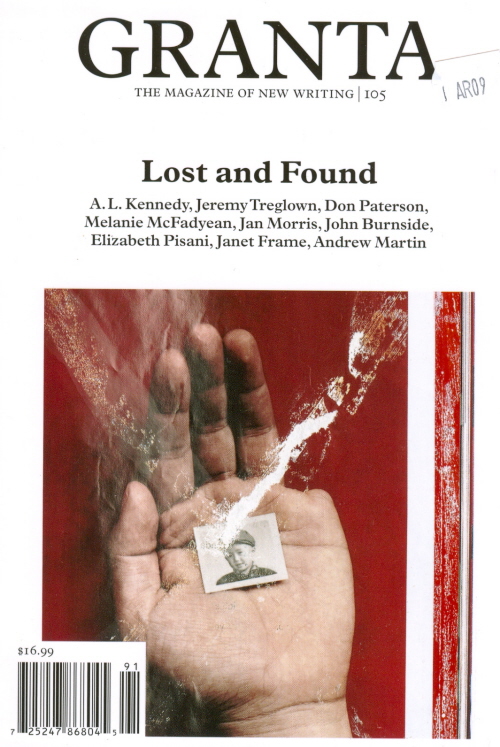

Tờ

Granta số mới

nhất, Mùa Xuân, 2009, đề tài Lost and Found, có mấy bài

viết về Thiên An Môn, 20 năm sau. Một, Chinese Whispers, một hồi ức về Đêm

Thiên

An Môn, của Elizabeth Pisani, một nữ phóng viên mới vô nghề, và những

kinh nghiệm

đầu đời trong đời ký giả của bà, qua những bản tin, records, gửi về toà

soạn: Như Graham, tôi chẳng bao giờ

quên nổi cái đêm trải qua ở Bắc Kinh đó. Nhưng

tôi đành chấp nhận sự kiện, là, những khung cảnh xuất hiện trong hồi ức

về nó,

thì cứ chập chờn thay đổi liên tục. Chúng ta có thể sửa đi sửa lại,

viết tới viết

lui những bản tin, những tường thuật như là chúng ta thích, nhưng chẳng

bao giờ

chúng ta kể, cùng một câu chuyện đó, hai lần

Một,

của một du khách, về kiểm duyệt tại TQ, bôi đen mấy dòng trên tờ

National Geographic.

Câu

bị bôi đen là: ‘... the Japanese

invasion to the Cultural

Revolution to the massacre around Tiananmen Square in 1989'. So this

was an

unusually provocative piece for National Geographic.

Cutting

Off Dissent:

Cắt ngón

tay li khai: Để phản đối biến cố Thiên An

Môn, 1989, nghệ sĩ Sheng Qi cắt ngón tay, tạo ra một số hình ảnh bàn

tay cụt ngón

tay của mình, trong có tấm hình ở nơi lòng bàn tay, là tấm hình một đứa

bé

trai.

Mất đi

và Kiếm lại được

*

EDITOR'S

LETTER

ALEX

CLARK

The

vanishing point:

Điểm biến

When

something is

lost, our

first instinct is often towards preservation: either of the thing

itself, its

memory and its traces in the world, or of the part of us that is

affected by

what is now missing. The pieces in this issue of Granta reflect on the

complex

business of salvage and try to bring into the light what we discover

when we

come face to face with loss.

It

is rarely a

straightforward process.

JeremyTreglown's

thought provoking exploration of the gathering movement to exhume the

victims

of the Spanish Civil War amply demonstrates the tensions created when a

desire

to commemorate clashes with a desire to move forward, and when both

entirely

natural impulses are claimed by other agendas. Although his

investigation

illuminates the continuing aftermath of a particularly dark and

disastrous

episode in Spanish history, it has clear parallels with other

countries'

attempts to recover from traumatic events and forces us to question

whether an

apparently simple urge to remember and to pay tribute can remain

uninflected by

other equally complex concerns.

A

similar ambiguity

informs

Maurice Walsh's dispatch from Ireland,

where he travelled to spend time with the Catholic priests whose

numbers have

been diminishing over the past few decades. He reports of a decline in

vocations that coincided with a widespread rise in secularism and an

attitude

towards the Church that hardened - perhaps irreversibly - after the

wave of

child-abuse scandals in the 1990s, which were seen not merely as

instances of

individual wrongdoing but as evidence of a collusion between a powerful

hierarchy and those whom it had sent into the community as trusted

individuals.

This shift in perspective has been well documented and, when the writer

and I

spoke about the piece in its earliest stages, we agreed that a fruitful

focus

would be what the priests themselves felt about this process of

marginalization.

Elsewhere,

we feature some

extremely personal stories, perhaps none more so than Melanie

McFadyean's

'Missing', which relates the experiences, over nearly two decades, of

the Needham

family. Ben

Needham, a child of twenty-one months, disappeared on the Greek island of Kos in 1991; he has never been

found.

The moment of his disappearance - the moment when he was last seen by

members

of his family - resonates through her account with its utter

simplicity; a

child, playing in the sun, running in and out of doors, being

completely

childlike and completely unselfconscious. Then silence, and absence;

and then

the continuing lives of Ben's mother, Kerry, his grandparents, his

uncles and

the sister born after he disappeared. It is a familiar fictional

device, and

often characteristic of the stories we tell ourselves about defining

periods in

our lives, to suggest that everything can change in an instant. Much of

the

time, that is not really true, and rather more likely that a crisply

delineated

sequence of events allows us to cope with chaos and confusion. In the

case of

the Needhams, though, even that world-altering single moment, viewed

through

the prism of different people and the passage of time, can remain

painfully

resistant to closure.

There

is a different kind of

examination of the past going on in Elizabeth Pisani's 'Chinese

Whispers', in

which the author recalls the night that she spent in Tiananmen Square

twenty

years ago, frantically attempting to phone in reports to her news

agency as

tanks (not to be confused with armored personnel carriers, as her

bosses on the

other end of the line curtly impressed on her) rolled in to crush the

ranks of

pro-democracy protestors filling the Square.

But

Pisani's resurrection of

a night that, to her, an inexperienced reporter of twenty-four, was the

most

momentous she had ever lived through, proves rather harder to pin down

in the

retelling. Is her version of events correct to the last detail? Or has

she

embroidered and finessed her memories in the intervening years?

Sometimes,

of course,

the

changing of the guard makes room for us to cast a lighter eye over

events, as

in Don Paterson's piece of memoir, which tells of his youthful passion

- and

passion is the right word - for evangelical Christianity, an effort to

exoticize his everyday life that led to fervent prayer sessions

enlivened by

the odd bout of angeloglossia. It seems that what he discovered as his

faith

faded was an unshakeable enthusiasm for rational thought. But he also

conjures,

as the best memoirs do, a portrait of another time - in this case, a

world of

weak tea, Jammie Dodgers and fearsome bullies. Equally evocative are

the pipe

smokers, captured in Andrew Martin's ode to a pleasure in peril, who

have found

themselves defending their commitment to a slower, temptingly detached

way of

life - their special brand of 'hypnotic latency', as Martin puts it.

In

among these surveys of

vanishing worlds come three pieces of fiction: an artfully poignant

story by

Janet Frame, a wry tale of dentistry and disarray by A. L. Kennedy and

two

pieces of work by Altan Walker. Of Earthly Love, Walker's debut novel,

was

several years in the writing, rewriting and recasting and had yet to be

finished when the writer died in 2007. As I began to read the

manuscript,

knowing that it would never now be completed, I felt immediately that

if it

were to remain unseen readers would be deprived of a true delight; one

that

would introduce them to a wild, shifting, ungovernable voice, capable

of great

acts of ventriloquism and imagination. It is a real pleasure to be able

to

publish part of Walker's

manuscript here and to know that, in among the varieties of loss that

we are

often subject to, there remain treasures to find. _

Elisabeth

Pisani là phóng viên, phần lớn viết cho Reuters, đã

từng tường thuật, trong khoảng 1986-1995, từ

India, China, Việt Nam, Cambode và những nơi khác. Bài viết cho số Granta, Lost

and Found, là toan tính tái sinh, resurrection, Đêm

Thiên An Môn bà đã từng trải qua, khi còn

là một phóng viên chưa có kinh nghiệm. Kể lại nó thế nào cho đúng sự

thực? Bài

viết là một suy tưởng về hồi ức, khi được viện tới, để kể lại một sự

kiện. Có những

nhận xét thật tuyệt, về sự kiện Thiên An Môn:

Foreigners

with a special interest in China know that 'the Tiananmen massacre'

acts as

a convenient shorthand for a much messier and certainly very bloody

reality

that affected the whole of Beijing. But for many other people

outside

China, the narrative has been rewritten around that single geographical

point.

For many people in China, of course, there's no narrative at all. The

events of

that night have been wiped from the record entirely. So much so that

three

editors on a provincial newspaper were sacked in 2007 because a young

clerk,

clueless about what had happened eighteen years before, allowed a

tribute to

the victims of '4/6' to slip into the classified ads column.

Journalism,

it is said, is the first draft of history. But this first draft is

edited

before it even hits the page, or the airwaves, by individual

journalists who

weave facts into a story that will engage the reader. It then gets

edited over

time into the dominant narrative. Details that seemed important to a

reporter

in the moment - friendly troops, babies on laps - get drowned by larger

events

and eventually disappear.

Nhân đây, post bài phỏng vấn Ma Jian, tác giả Hôn Thuỵ Bắc Kinh, của tờ

L'Express, số đề ngày 14 Tháng Sáu, 2009.

*

DOCUMENT

Ma Jian

« En Chine, chaque jour

est un 4 juin

1989 »

Il serait l' « une des

voix les plus

courageuses et les plus importantes de la litttérature chinoise

actuelle »,

selon Gao Xingjian, prix Nobel de littérature ... Vingt ans après

l'écrasement

sanglant de Tiananmen, le 4 juin 1989, Ma Jian revient sur le Printemps

de

Pékin, qui fournit la trame de son roman magistral, Beijing Coma

(Flammarion),

dont paraît ce mois-ci la version en mandarin. Ancien photographe au

service de

propagande des syndicats chinois, cet écrivain inclassable a fui Pékin,

au

début des années 1980, et traversé le pays de part en part, trois ans

durant.

Après l'interdicction d'une de ses nouvelles, il choisit l'exil à

Hongkong,

puis à Londres, où il vit désormais. Dans son dernier opus, le

narrateur gît

dans un coma éveillé après avoir reçu une balle dans la tête, place

Tiananmen.

Alors qu'il se remémore les événements qui ont précédé la nuit tragique

du 4

juin, le monde change autour de lui...

Tại TQ mỗi ngày là một Tứ

Lục, 1989

|

|