|

Auden thought of poetry as dual: poetry as song, poetry as truth. It's perhaps this that, in his poem Their Lonely Betters', written in 1950, made him sceptical of birds who sing without feeling and with no regard for truth. Auden coi thơ là song ẩm: Thơ như bài hát, thơ như sự thực. Vì thế ông không khoái tiếng chim hót: Cảm xúc, chân lý cái con mẹ gì ở trong đó? Their Lonely Betters

As I listened from a beach-chair in the shade To all the noises that my garden made, It seemed to me only proper that words Should be withheld from vegetables and birds. A robin with no Christian name ran through The Robin-Anthem which was all it knew, And rustling flowers for some third party waited To.say which pairs, if any, should get mated. Not one of them was capable of lying, There was not one which knew that it was dying Or could have with a rhythm or a rhyme Assumed responsibility for time. Let them leave language to their lonely betters Who count some days and long for certain letters; We, too, make noises when we laugh or weep: Words are for those with promises to keep.

W.H. Auden

A Passion of Poets By Joseph Brodsky Oct 1983 I

When a writer resorts to a language other than his mother

tongue, he does so either out of necessity, like Conrad, or because

of burning ambition, like Nabokov, or for the sake of greater estrangement,

like Beckett. Belonging to a different league, in the summer of 1977,

in New York, after living in this country for five years, I purchased

in a small typewriter shop on Sixth Avenue a portable "Lettera 22"

and set out to write (essays, translations, occasionally a poem) in

English for a reason that had very little to do with the above. My

sole purpose then, as it is now, was to find myself in closer proximity

to the man whom I considered the greatest mind of the twentieth century:

Wystan Auden.https://www.enotes.com/topics/less-than-one Khi Brodsky bị lưu đày nội xứ vì cái tội ăn bám xã hội, ông nhận được 1 tuyển tập thơ, của ai đó, gửi tặng, trong có bài thơ của Auden,“In Memory of W.B. Yeats”. Bài thơ làm ông ngộ ra, như Remnick viết. Trong bài viết "Để làm hài lòng 1 cái bóng", được trích đoạn với cái tít "Một đam mê thi sĩ", ông kể, về cái chuyện ông mua 1 cái máy đánh chữ, tập viết bằng tiếng Anh, chỉ để thân cận với nhà thơ Auden, "cái đầu vĩ đại nhất của thế kỷ 20", khác với một Conrad, do cần thiết, hay Nabokov, do háo danh, hay Beckett, do thèm ghẻ lạnh. Tôi hết còn tin vào nơi chốn ấy Sau cùng ông bị kết án năm năm, lưu đầy nội xứ. Ông làm việc tại một trang trại ở Norinskaya, vùng đất sũng nước gần Bạch Hải. Chỉ có Akhmatova, người đã từng trải qua những nỗi thống khổ nhiều hơn thế nữa, đã từng mất bao nhiêu thân quyến, bao nhiêu bạn bè trong cái lò xay thịt người là những năm tháng dưới sự thống trị của Lênin và Stalin, chỉ có bà mới có thể nở một nụ cười kèm theo lời nhận xét cay đắng: "Hãy tưởng tượng bản tự thuật mà họ đang sáng tạo cho thằng em tóc hung của chúng ta? Chính anh ta đã mướn tụi nó làm đấy!" Khi được hỏi ông nghĩ gì về những năm tháng tù đầy, Brodsky nói cuối cùng ông đã vui với nó. Ông vui với việc đi giầy ủng và làm việc trong một nông trại tập thể, vui với chuyện đào xới. Biết rằng mọi người suốt nước Nga hiện cũng đang đào xới "cứt đái", ông cảm thấy cái gọi là tình tự dân tộc, tình máu mủ. Ông không nói giỡn. Buổi chiều ông có thời giờ ngồi làm những bài thơ "xấu xa", và tự cho mình bị quyến rũ bởi "chủ nghĩa hình thức trưởng giả" từ những thần tượng của ông. Hai đoạn thơ sau đây của Auden đã làm ông "ngộ" ra: Time that is intolerant Of the brave and innocent, And indifferent in a week To a beautiful physique, Worships language and forgives Everyone by whom it lives; Pardons cowardice, conceit, Lays its honor at their feet. Thời gian vốn không khoan dung Đối với những con người can đảm và thơ ngây, Và dửng dưng trong vòng một tuần lễ Trước cõi trần xinh đẹp, Thờ phụng ngôn ngữ và tha thứ Cho những ai kia, nhờ họ, mà nó sống; Tha thứ sự hèn nhát và trí trá, Để vinh quang của nó dưới chân chúng. Auden Ông bị xúc động không hẳn bởi cách mà Auden truyền đi sự khôn ngoan - làm bật nó ra như trong dân ca - nhưng bởi ngay chính sự khôn ngoan, ý nghĩa này: Ngôn ngữ là trên hết, xa xưa lưu tồn dai dẳng hơn tất cả mọi điều khác, ngay cả thời gian cũng phải cúi mình trước nó. Brodsky coi đây là đề tài cơ bản, trấn ngự của thi ca của ông, và là nguyên lý trung tâm của thơ xuôi và sự giảng dạy của ông. Trong cõi lưu đầy như thế đó, ông không thể tưởng tượng hai mươi năm sau, khăn đóng, áo choàng, ông bước lên bục cao nơi Hàn lâm viện Thụy-điển nhận giải Nobel văn chương, nói về tính độc đáo của văn chương không như một trò giải trí, một dụng cụ, mà là sự trang trọng, bề thế xoáy vào tinh thần đạo đức của nhân loại. Nếu tác phẩm của ông là một thông điệp đơn giản, đó là điều ông học từ đoạn thơ của Auden: "Sự chán chường, mỉa mai, dửng dưng mà văn chương bày tỏ trước nhà nước, tự bản chất phải hiểu như là phản ứng của cái thường hằng - cái vô cùng - chống lại cái nhất thời, sự hữu hạn. Một cách ngắn gọn, một khi mà nhà nước còn tự cho phép can dự vào những công việc của văn chương, khi đó văn chương có quyền can thiệp vào những vấn đề của nhà nước. Một hệ thống chính trị, như bất cứ hệ thống nào nói chung, do định nghĩa, đều là một hình thức của thời quá khứ muốn áp đặt chính nó lên hiện tại, và nhiều khi luôn cả tương lai..." Trong số báo trên TV đã giới thiệu bài viết của Gordimer. Kiếm mãi không thấy, bèn post lại. (1) WOLE SOYINIKA

Albert Camus wrote, "One either serves the whole of man or one

does not serve him at all. And if man needs bread and justice, and if

what has to be done must be done to serve this need, he also needs pure

beauty which is the bread of his heart," and so Camus called for "courage

in one's life and talent in one's work." Wole Soyinka. This great Nigerian

writer has in his writings and in the conduct of his life served the whole

of humankind. He endured imprisonment in his dedication to the fight for

bread and justice, and his works attain the pure beauty of imaginative

power that fulfills that other hungry need, of the spirit. He has "courage

in his life and talent in his work." In Soyinka's fearless searching of

human values, which are the deep integument of even our most lyrical poetry,

prose, and whatever modes of written-word-created expression we devise,

he never takes the easy way, never shirks the lifetime commitment to write

as well as he can. In every new work he zestfully masters the challenge that

without writing as well as we can, without using the infinite and unique

possibilities of the written word, we shall not deserve the great responsibility

of our talent, the manifold sensibilities of the lives of our people which

cannot be captured in flipped images and can't be heard in the hullabaloo

of mobile-phone chatter. Bread, justice, and the bread of the heart-which

is the beauty of literature, the written word-Wole Soyinka fulfills all these.THE LITERARY LION By Nadine Gordimer JULY 2007 (1): Kiếm thấy rồi: http://www.tanvien.net/Day_TV/35.html "One either serves the whole of man or one does not serve him at all. And if man needs bread and justice, and if what has to be done must be done to serve this need, he also needs pure beauty which is the bread of his heart," and so Camus called for "courage in one's life and talent in one's work." Hoặc là mi phục vụ, trọn con người, hoặc là mi vờ nó, cái gọi là trọn con người. Và nếu con người cần bánh mì, và công lý, và nếu hai cái cần này của nó được thoả mãn, thì nó còn cần cái đẹp tinh khiết, là bánh mì của trái tim của nó, và thế là Camus bèn la lớn, "bớ người ta", hãy "can đảm trong cuộc đời và tài năng trong cuộc viết". Cái gọi là can đảm của đàn ông Mít, bị cuộc chiến Mít làm thịt sạch. Đéo có tí can đảm, là đéo viết được. Tinh anh Ngụy, chết vì mảnh bằng, là vì vậy. Nhắc tới Camus, bèn giới thiệu cuốn mới mua

Six

Poets Hardy to Larkin

W H. Auden 1907-1973 Wystan

Hugh Auden was born in York, brought up in Birmingham, where his father

was a physician, and educated at Gresham's School, Holt, and Christ Church,

Oxford. His student contemporaries included poets Cecil Day Lewis, Louis

MacNeice and Stephen Spender. After graduating in 1929, he spent several

months in Berlin, often in the company of Christopher Isherwood, his future

collaborator. His first book, Poems, was published in 1930 by T. S. Eliot

at Faber and Faber and he later became associated with Rupert Doone's Group

Theatre, for which he wrote several plays, sometimes in collaboration with

Isherwood. In January 1939 the two of them left England for the United

States, where Auden became a citizen in 1946. His later works include The

Age of Anxiety, Nones, The Shield of Achilles and Homage to Clio, and he

also wrote texts for works by Benjamin Britten and (with Chester Kallman)

the libretto for Stravinsky's opera The Rake's Progress. Elected Professor

of Poetry at Oxford in 1956, he died in Vienna in 1973.

Nobody

in the thirties was quite sure what war would be like, whether there

would be gas, for instance, or aerial bombardment. There's a stock and

rather a silly question: 'Why was there no poetry written in the Second

World War?' One answer is that there was, but it was written in the ten

years before the war started.

Auden was a landscape poet, though of a rather particular kind. The son of a doctor, he was born in York in 1907 but brought up in Solihull in the heart of the industrial Midlands. Not the landscape of conventional poetic inspiration but, for Auden, magical: from Letter to Lord Byron

But let me

say before it has to go, It's the most lovely country that I know; Clearer than Scafell Pike, my heart has stamped on The view from Birmingham to Wolverhampton. Long, long ago, when I was only four, Going towards my grandmother, the line Passed through a coal-field. From the corridor I watched it pass with envy, thought 'How fine! Oh how I wish that situation mine.' Tramlines and slagheaps, pieces of machinery, That was, and still is, my ideal scenery. At Oxford, he was already writing and

publishing poetry. To his contemporaries, he was a magnetic figure, partly

because he seemed to have all the answers, a characteristic that his

later self came to deplore, though he remained a bit of an intellectual

bully all his life. As a man, he was insecure and unhappy and doesn't

seem to have fallen in love until he went to America in 1939, but this didn't

stop him prescribing for the love affairs of his friends. The Danish philosopher

Kierkegaard says that there are two ways: one is to suffer; the other is

to become a professor of the fact that another suffers. Auden was to play

both roles in His time; but when he was an undergraduate, he was undoubtedly

a professor.

Who's Who How Father beat him, how he ran away, What were the struggles of his youth, what acts Made him the greatest figure of his day: Of how he fought, fished, hunted, worked all night, Though giddy, climbed new mountains; named a sea: Some of the last researchers even write Love made him weep his pints like you and me. With all his honours on, he sighed for one Who, say astonished critics, lived at home; Did little jobs about the house with skill And nothing else; could whistle; would sit still Or potter round the garden; answered some Of his-long marvellous letters but kept none. Auden taught at various prep schools in the early thirties, and one of the criticisms that contemporaries made of his poetry was that his view of the world was dictated by his unhappy experiences at school. The best reason I have for opposing Fascism', he said, 'is that at school I lived in a Fascist state.' Not a statement that would commend itself to someone actually having to live in a Fascist state, and the kind of remark that made him blush once he got away from England in 19.39. 'All the verse I wrote,' Auden said later, all the positions I took in the thirties didn't save a single Jew. These writings, these attitudes only help oneself They merely make people who think like one admire and like one, which is rather embarrassing. Which is true, but which says nothing about the poetry, and embarrassing though the older Auden found his younger self, the poetry of that younger self survives the embarrassment. The turning point in Auden's life came, or is supposed to have come, when he and Isherwood went to the Umted States at the start of 1939 and stayed there, both eventually becoming American citizens. Silly people at the time took this to be cowardice, which it wasn't, and even people who admired him thought Auden's poetry was never as good afterwards. But this wasn't true either. Why Auden left England has been much discussed. Auden liked feeling at home, but he didn't like feeling at home where he felt at home. England was too cosy. He would never grow up there, he thought. He would always be the enfant terrible, the prisoner of his public and court poet to the Left. At least this is how Auden came to see it. But it wasn't quite like that either. All that had happened was that he had gone to America in 1939, seemingly with no plans to stay, and, for the first time in his life, he had fallen in love - with Chester Kallman, with whom he was to live happily and unhappily for the rest of his life. It just happened that change in private places went with change in public places, love and war coinciding: Auden really was just an early 'GI bride'. Somebody who cared more about what people thought would have come back when war started, but Auden - and it was one of the winning characteristics in a personality that was not always attractive - didn't care tuppence what people thought. As it transpired, going to America turned out to be a deliverance, the kind of escape an established writer often craves, a way of eluding his public, of not having to go on writing in the same way, of not having to imitate himself 'By the time you have perfected any style of writing', said George Orwell, 'you have always outgrown it.' 'You spend twenty-five years learning to be yourself,' said Auden, 'and then you find you must now start learning not to be yourself - and it took him a while. This next poem Auden called a 'hangover from home'. He wrote it in America, but one of the reasons he left England, he said, was to stop writing poetry like this. In America, Auden's poetry began to take on a different tone. His 'old grand manner', as he described it, proceeded from 'a resonant heart'. With the war and the Cold War that followed: from We Too Had Known Golden Hours All sane affirmative speech, Had been soiled, profaned, debased To a horrid mechanical screech.

Hardy never said much about writing or the difficulties of it, or the moral difficulties of it. Kafka said that a writer was doing the devil's work, writing a wholly inadequate response to the brutishness of the world, and Hardy increasingly felt this. It's not that it's an immoral activity or an amoral one; it's just that the act of creation is something to which the ordinary standards of human behavior do not apply. Hardy never liked to be touched. He always walked in the road to avoid brushing against people, and servants were told never to help him on with his coat and just to drop the shawl around his shoulders and not tuck him in. The pen had been his weapon in his struggle for life - and it had been a struggle. The next poem is a dialogue with the moon. Hardy chẳng hề lầu bầu về viết, hay những khó khăn về viết, hay khó khăn đạo đức của nó. Kafka phán nhà văn làm, việc của quỉ, viết trọn một phúc đáp không thoả đáng về tính thú vật của thế giới, và Hardy càng ngày càng cảm thấy đúng như thế. Nó không phải là 1 hành động đạo đức, hay không đạo đức, mà cái hành động sáng tạo có 1 điều gì mà lũ chó, hay phường mắt trắng dã, không hiểu được, hay, không áp dụng được. Hardy đếch khoái ai đụng vô ông ta. Cây viết là vũ khí của ông ta, trong cuộc chiến đấu với đời – và quả có cuộc chiến đấu đó thực. Bài thơ sau đây là 1 cuộc lèm bèm với trăng. I Looked Up from My Writing

I looked up

from my writing, And gave a start to see, As if rapt in my inditing, The moon's full gaze on me. Her meditative misty head Was spectral in its air, And I involuntarily said, 'What are you doing there?' 'Oh, I've been scanning pond and hole And waterway hereabout For the body of one with a sunken soul Who has put his life-light out. 'Did you hear his frenzied tattle? It was sorrow for his son Who is slain in brutish battle, Though he has injured none. 'And now I am curious to look Into the blinkered mind Of one who wants to write a book In a world of such a kind.' Her temper overwrought me, And I edged to shun her view, For I felt assured she thought me One who should drown him too.

Cuốn này,

do Anthony biên tập và viết Tựa, cũng có 1

bản dịch bài Golem. THE PLOT

To

make his horror complete, Caesar, pursued to the base of a statue

by the relentless daggers of his friends, discovers among the faces

'and blades the face of Marcus Junius Brutus, his favorite, his son perhaps,

and he ceases to defend himself to exclaim: "You too, my son!" Shakespeare

and Quevedo echo the pathetic cry. Fate takes pleasure in repetitions,

variants, symmetries. Nineteen centuries later, in the south of Buenos Aires province, a gaucho is assaulted by other gauchos, and, as he falls, recognizes a godson and with gentle reproach and gradual surprise exclaims (these words must be heard, not read): "But che!" He is killed and never knows he dies so that a scene may be re-enacted. -Translated by ELAINE KERRIGAN Để cho nỗi kinh hoàng ghê rợn, được trọn vẹn, Sáu Dân, bị rượt đuổi bởi những đấng bạn quí Bắc Kít, đấng nào cũng lăm lăm 1 cây dao găm, nhận ra rằng, trong số đó, có cả đứa con nuôi của mình, đứa mà ông quí nhất, là Tà Lọt, Ô Sin, ông bèn ngưng chống cự, và la lên, "Con đó ư, Bố, Sáu Dân nè!" [Cả con nữa ư, Osin!] Shakespeare và Quevedo lập lại tiếng kêu thống thiết. Số mệnh - Cái Ác Bắc Kít thì cũng được - khám phá ra cái thú vui sa đích của nó, trong lập lại, ứng tác, đối xứng Note: Bài viết ngắn của Borges, cũng là 1 sự lập lại. Đoạn sau, đúng như trên, là câu chuyện Tà Lọt & Sáu Dân: 19 thế kỷ qua đi, tại thành phố Xề Gòn.... Những từ này, phải nghe bằng tiếng Nam Kít, không đọc được... THE GIFTS

Let

no one debase with pity or reprove This declaration of God's mastery Who with magnificent irony Gave me at once books and the night. Of this city of books he made two Lightless eyes the owners, eyes that can Read only in the library of dreams Those senseless paragraphs that surrender The dawns to their desire. In vain the day Lavishes on them its infinite books, Arduous as those arduous manuscripts That were destroyed in Alexandria. Of hunger and thirst (a Greek story has it) A king dies amid fountains and gardens; I drudge aimlessly about the limits Of this enormous library of my blindness. Encyclopedias, atlases, the East And the West, centuries, dynasties, Symbols, cosmos, and cosmogonies Entice from the walls, but uselessly. Within my darkness I slowly explore The hollow half light with hesitant cane, I who always imagined Paradise To be a sort of library. Something, which certainly is not named By the word chance, governs these things; Some other already received on other faded Afternoons the many books and the dark. Wandering through the heavy galleries, I often feel with sacred vague horror That I am that other, the dead one, who will Have walked here too and on these very days. Which of us is writing this poem With plural I and a single darkness? What difference the word that names me If the curse is undivided and single? Groussac or Borges, I look at this dear World which collapses and goes out In a pale indefinite ash That resembles both the dream and oblivion. -Translated by IRVING FELDMAN THE MOON

History

tells us that in such time past when so many real, imaginary and doubtful things took place, one m~n conceived the unwieldy Plan of ciphering the universe in one book and, infinitely rash, built his high and mighty manuscript, shaping and declaiming the final line. But when about to praise his luck, he lifted up his eyes, and saw a burnished disk upon the air; startled, he realized he'd left out the moon. Though contrived, this little story might well exemplify the mischief that involves us all who take on the job of turning real life into words. Always the essential thing gets lost. That's one rule holds true of every inspiration. Nor will this resume of my long association with the moon escape it. I don't know when I saw it first- if in the sky prior to the doctrine of the Greek, or in the evening darkening over the patio with the fig tree and the well. As they say, this unpredictable life can be, among other things, quite beautiful. That's how it was the evening we looked at you, she and I--oh, shared moon! Better than real nighttime moons, I can recall the moons of poetry: the bewitched dragon moon that thrills one in the ballad, and, of course, Quevedo's bloody moon. Then there was that other blood-red moon John wrote of in his book of dreadful prodigies and terrifying jubilees; still other moons are clearer, silvery. Pythagoras (according to one tradition) used blood to write upon a mirror, and men read it by reflection in that other mirror called the moon. There's an iron forest where a huge wolf lives whose strange fate is to knock the moon down and murder it when the last dawn reddens the sea. (This is well known in the prophetic North; also, that on that day the ship made out of all the fingernails of the dead will spread a poison on the world's wide-open seas.) When in Geneva or in Zurich once, luck had it I too should become a poet, it imposed on me, as on the rest, the secret duty to define the moon. By dint of scrupulous study, I rang all the modest changes under the lively apprehension that Lugones might have used my amber or my sand. As for exotic marble, smoke, cold snow- these were for moons that lit up verses never destined, in truth, to attain the difficult distinction of typography. I thought the poet such a man as red Adam was in Paradise- he gave everything its true, precise, still unknown name. Ariosto taught me that living in the doubtful moon are all dreams, the unattainable, lost time, all possibles or impossibles (they're pretty much the same). Apollodorus showed me the magic shadow of triform Diana; Hugo disclosed its golden sickle; an Irishman his tragic moon of black. So, while I was poking in this mine of moons out of mythologies, along it came, around the corner: the celestial moon of every day. Among the words, I know there's only one for remembering or imagining it. For me the secret is to use the word humbly. And the word is-moon. Now I don't dare stain its immaculate appearance with one vain image. I see it as indecipherable, daily and apart from all my writing. I know the moon, or the word moon, is a: character created for the complex inditing of the rare thing we all are, multiple and unique. It's one of the symbols which fate or chance gave man so that one day in a glorious blaze, or agony, he'd learn to write his own true name. -Translated by EDWIN HONIG Trăng

( Đặng Lệ Khánh)

TRĂNG Em bước ra vườn, trăng chảy tràn trên vai Vườn rất im không một tiếng thở dài Chỉ có con dế quen cất giọng chào đêm tới Và nước trong hồ gờn gợn cá gọi mời Em ngước nhìn trời, trăng thật sáng, thật trong Lành lạnh khuya dâng, mình ôm mình vào lòng Trăng cứ lăn hoài làm sao trăng còn nhớ Những câu thề theo trăng rồi tan vào hư không Em nói với trăng dù biết trăng rất xa Những lời dịu êm em dành cho người ta Chỉ có con dế quen và em và đêm biết Trăng nhẹ nhàng theo em vào giấc ngủ thêu hoa Năm rồi năm đi qua trăng vẫn còn lăn hoài Trời vẫn rất trong và đêm vẫn miệt mài Con dế quen thôi không còn cất tiếng Em ôm vai mình dỗ tròn cơn mộng dài Thế giới quay cuồng, đất và trời chuyển rung Có rất nhiều tiếng cười, và tiếng khóc chập chùng Em vẫn nằm co người đếm trừu chờ giấc ngủ Níu một vầng trăng đã lạnh tuổi thu đông Đặng Lệ Khánh

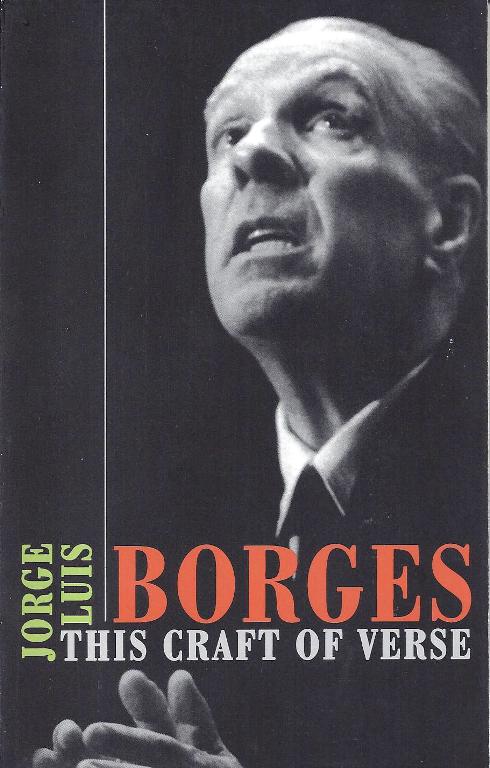

The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures 1967-1968 Trong

bài viết Ẩn Dụ, trong cuốn This Craft of Verse,

Borges có nhắc tới 1 câu thơ, "phản bác" trăng -

đây cũng là ý nghĩa bài thơ Tặng Phẩm, theo

GCC, vì trao cho cả thư viện sách, cùng lúc

trao cho món quà, mù - mà ông

nghĩ là của Plato:

Tớ mong tớ là đêm để có thể ngắm em của tớ ngủ, với cả ngàn con mắt! I wish I were the night so that I might watch your sleep with a thousand eyes Hardy never said much about writing or the difficulties of it, or the moral difficulties of it. Kafka said that a writer was doing the devil's work, writing a wholly inadequate response to the brutishness of the world, and Hardy increasingly felt this. It's not that it's an immoral activity or an amoral one; it's just that the act of creation is something to which the ordinary standards of human behavior do not apply. Hardy never liked to be touched. He always walked in the road to avoid brushing against people, and servants were told never to help him on with his coat and just to drop the shawl around his shoulders and not tuck him in. The pen had been his weapon in his struggle for life - and it had been a struggle. The next poem is a dialogue with the moon. Hardy chẳng hề lầu bầu về viết, hay những khó khăn về viết, hay khó khăn đạo đức của nó. Kafka phán nhà văn làm, việc của quỉ, viết trọn một phúc đáp không thoả đáng về tính thú vật của thế giới, và Hardy càng ngày càng cảm thấy đúng như thế. Không phải đạo đức, hay không đạo đức, hành động sáng tạo có 1 điều gì, lũ chó, hay phường mắt trắng dã, không hiểu được, hay, không áp dụng được. Hardy đếch khoái ai đụng vô ông ta. Cây viết là vũ khí của ông ta, trong cuộc chiến đấu với đời – và quả có cuộc chiến đấu đó thực. Bài thơ sau đây là 1 cuộc lèm bèm với trăng. I Looked Up from My Writing

I looked

up from my writing, And gave a start to see, As if rapt in my inditing, The moon's full gaze on me. Her meditative misty head Was spectral in its air, And I involuntarily said, 'What are you doing there?' 'Oh, I've been scanning pond and hole And waterway hereabout For the body of one with a sunken soul Who has put his life-light out. 'Did you hear his frenzied tattle? It was sorrow for his son Who is slain in brutish battle, Though he has injured none. 'And now I am curious to look Into the blinkered mind Of one who wants to write a book In a world of such a kind.' Her temper overwrought me, And I edged to shun her view, For I felt assured she thought me One who should drown him too. Tớ nhìn lên từ trang

viết của mình

Tớ nhìn lên từ trang viết Và rất ư hài lòng vì cái viết của mình Và bèn ngắm trăng Và trăng bèn dành trọn cái nhìn, đáp lại tớ Cái đầu mù sương mù suy tư của nàng Thì mới ma mị làm sao trong cái "air" của nó Và tớ bèn vô tình phán, Em đang làm gì ở trên ấy? Ôi, ta đang soi ao, và hố Và sông hồ đâu đây Để kiếm tìm một cái xác Của một kẻ, với linh hồn đắm chìm Đã trút cạn ánh sáng cuộc đời của nó Mi có nghe hắn lèm bèm khùng điên? Về nỗi đau buồn đứa con trai Chết trong 1 trận đánh tàn bạo Dù thằng con chẳng gây thương tích cho ai Và bây giờ ta tò mò muốn nhìn vào cái đầu mù của mi Kẻ muốn viết 1 cuốn sách Trong 1 thế giới khốn kiếp như thế đó! Tính khí của nàng làm tôi mệt nhoài Và tôi tránh cái nhìn của nàng Bởi là vì tôi cảm thấy Nàng nghĩ Tôi cũng là 1 trong số những người đẩy anh ta tự trầm

Auden

thought of poetry as dual: poetry as song, poetry as truth. It's

perhaps this that, in his poem Their Lonely Betters', written in 1950,

made him sceptical of birds who sing without feeling and with no regard

for truth.

Auden nghĩ thơ thì lưỡng, kép, có đôi: thơ như bài hát, bài ca;thơ như sự thực. Có lẽ vì thế, mà trong bài thơ dưới đây, cho thấy, ông hoài nghi chim chóc, chúng hát, mà không có "feeling" cái con mẹ gì, và cũng đếch thèm để ý đến sự thực! Their Lonely Betters

As I listened from a beach-chair in the shade To all the noises that my garden made, I t seemed to me only proper that words Should be withheld from vegetables and birds. A robin with no Christian name ran through The Robin-Anthem which was all it knew, And rustling flowers for some third party waited To.say which pairs, if any, should get mated. Not one of them was capable of lying, There was not one which knew that it was dying Or could have with a rhythm or a rhyme Assumed responsibility for time. Let them leave language to their lonely betters Who count some days and long for certain letters; We, too, make noises when we laugh or weep: Words are for those with promises to keep. Auden died in Vienna in 1973, when he was only sixty-six, but it would be hard to say his work was not finished. His output had been prodigious, and he went on working right until the end in a routine that was every bit as rigid as that of Housman, whom he so briskly diagnosed when he was a young man (,Deliberately he chose the dry-as-dust, / Kept tears like dirty postcards in a drawer'). But you're no more likely to find consistency in a writer than you would in a normal human being. Besides, as Auden himself said: 'At thirty I tried to vex my elders. Past sixty it's the young whom I hope to bother.' I would be hard put to say what a great poet is, but part of it, in Auden's case, is the obscurity with which I started. If his life has to be divided into two parts, there are great poems in both. Perhaps he was too clever for the English. Bossy and not entirely likeable, when he died his death occasioned less regret than that of Larkin or Betjeman, though he was the greater poet. This would not have concerned him as he was not vain: criticism seldom bothered him nor did he covet praise or money. And though he would have quite liked the Nobel Prize, all he demanded at the finish was punctuality. I'll end with the final part of the poem Auden wrote in memory of another poet, W. B. Yeats, who died in January 1939. The last two lines are inscribed on Auden's memorial in Westminster Abbey. Hai dòng thơ chót bài thơ tưởng niệm Yeats được khắc trên mộ bia của Auden. In the prison of his days Teach the free man how to praise. Bài thơ thần sầu này mở ra cõi thơ của Brodsky, như David Remnick viết: Hai đoạn thơ sau đây của Auden đã làm ông "ngộ" ra: Time that is intolerant Worships language and forgives Thời gian vốn không khoan

dung Thờ phụng ngôn ngữ và

tha thứ Auden from In Memory of W B. Yeats

Earth,

receive an honoured guest: (d. Jan. /939) William Yeats is laid to rest. Let the Irish vessel lie Emptied of its poetry. Time that is intolerant Of the brave and innocent, And indifferent in a week To a beautiful physique, Worships language and forgives Everyone by whom it lives; Pardons cowardice, conceit, Lays its honours at their feet. Time that with this strange excuse Pardoned Kipling and his views, And will pardon Paul Claudel, Pardons him for writing well. In the nightmare of the dark All the dogs of Europe bark, And the living nations wait, Each sequestered in its hate; Intellectual disgrace Stares from every human face, And the seas of pity lie Locked and frozen in each eye. Follow, poet, follow right To the bottom of the night, With your unconstraining voice Still persuade us to rejoice; With the farming of a verse Make a vineyard of the curse, Sing of human unsuccess In a rapture of distress; In the deserts of the heart Let the healing fountain start, In the prison of his days Teach the free man how to praise. http://tanvien.net/Dayly_Poems/Auden.html

Tưởng niệm Yeats

I Nhà thơ biến mất vào cái chết mùa đông Những con suối đóng băng, những phi trường gần như bỏ hoang Và tuyết huỷ hoại những pho tượng công cộng Thời tiết chìm vào trong miệng của ngày chết Ôi, tất cả những công cụ thì đều đồng ý Ngày nhà thơ mất đi là một ngày lạnh giá, âm u. Thật xa sự bịnh hoạn của ông Những con chó sói băng qua những khu rừng xanh rờn Con sông nơi quê mùa chẳng bị cám dỗ bởi những bến cảng sang trọng Bằng những giọng tiếc thương Cái chết của thi sĩ được tách ra khỏi những bài thơ của ông. Nhưng với ông, thì đây là buổi chiều cuối cùng, như chính ông Một buổi chiều với những nữ y tá và những tiếng xầm xì; Những địa phận trong cơ thể ông nổi loạn Những quảng trường trong tâm trí ông thì trống rỗng Sự im lặng xâm lăng vùng ngoại vi Dòng cảm nghĩ của ông thất bại: ông trở thành những người hâm mộ ông Bây giờ thì ông phân tán ra giữa hàng trăm đô thị Với trọn một mớ cảm xúc khác thường; Tìm hạnh phúc của ông ở trong một cảnh rừng khác Bị trừng phạt bởi một luật lệ ngoại về lương tâm. Nhưng trong cái quan trọng và tiếng ồn của ngày mai Khi đám brokers gầm rú như những con thú ở sàn Chứng Khoán, Và những người nghèo đau khổ như đã từng quen với đau khổ, Và mỗi kẻ, trong thâm tâm của chính kẻ đó, thì hầu như đều tin tưởng ở sự tự do của nhà thơ; Và chừng vài ngàn người sẽ nghĩ về ngày này Như 1 kẻ nghĩ về một ngày khi một kẻ nào đó làm một điều không giống ai, khác lệ thường Ôi, bao nhiêu công cụ thì đều đồng ý Ngày nhà thơ ra đi thì là một ngày âm u, giá lạnh II Bạn thì cũng cà chớn như chúng tớ: Tài năng thiên bẩm của bạn sẽ sống sót điều đó, sau cùng; Nào cao đường minh kính của những mụ giầu có, sự hóa lão của cơ thể. Chính bạn; Ái Nhĩ Lan khùng đâm bạn vào thơ Bây giờ thì Ái Nhĩ Lan có cơn khùng của nó, và thời tiết của ẻn thì vưỡn thế Bởi là vì thơ đếch làm cho cái chó gì xẩy ra: nó sống sót Ở trong thung lũng của điều nó nói, khi những tên thừa hành sẽ chẳng bao giờ muốn lục lọi; nó xuôi về nam, Từ những trang trại riêng lẻ và những đau buồn bận rộn Những thành phố nguyên sơ mà chúng ta tin tưởng, và chết ở trong đó; nó sống sót, Như một cách ở đời, một cái miệng. III Đất, nhận một vị khách thật là bảnh William Yeats bèn nằm yên nghỉ Hãy để cho những con tầu Ái nhĩ lan nằm nghỉ Cạn sạch thơ của nó [Irish vessel, dòng kinh nguyệt Ái nhĩ lan, theo nghĩa của Trăng Huyết của Minh Ngọc] Thời gian vốn không khoan dung Đối với những con người can đảm và thơ ngây, Và dửng dưng trong vòng một tuần lễ Trước cõi trần xinh đẹp, Thờ phụng ngôn ngữ và tha thứ Cho những ai kia, nhờ họ, mà nó sống; Tha thứ sự hèn nhát và trí trá, Để vinh quang của nó dưới chân chúng. Thời gian với nó là lời bào chữa lạ kỳ Tha thứ cho Kipling và những quan điểm của ông ta Và sẽ tha thứ cho… Gấu Cà Chớn Tha thứ cho nó, vì nó viết bảnh quá! Trong ác mộng của bóng tối Tất cả lũ chó Âu Châu sủa Và những quốc gia đang sống, đợi, Mỗi quốc gia bị cầm tù bởi sự thù hận của nó; Nỗi ô nhục tinh thần Lộ ra từ mỗi khuôn mặt Và cả 1 biển thương hại nằm, Bị khoá cứng, đông lạnh Ở trong mỗi con mắt Hãy đi thẳng, bạn thơ ơi, Tới tận cùng của đêm đen Với giọng thơ không kìm kẹp của bạn Vẫn năn nỉ chúng ta cùng tham dự cuộc chơi Với cả 1 trại thơ Làm 1 thứ rượu vang của trù eỏ Hát sự không thành công của con người Trong niềm hoan lạc chán chường Trong sa mạc của con tim Hãy để cho con suối chữa thương bắt đầu Trong nhà tù của những ngày của anh ta Hãy dạy con người tự do làm thế nào ca tụng. Six

Poets Hardy to Larkin

W H. Auden 1907-1973 Wystan

Hugh Auden was born in York, brought up in Birmingham, where his father was

a physician, and educated at Gresham's School, Holt, and Christ Church, Oxford.

His student contemporaries included poets Cecil Day Lewis, Louis MacNeice

and Stephen Spender. After graduating in 1929, he spent several months in

Berlin, often in the company of Christopher Isherwood, his future collaborator.

His first book, Poems, was published in 1930 by T. S. Eliot at Faber and

Faber and he later became associated with Rupert Doone's Group Theatre, for

which he wrote several plays, sometimes in collaboration with Isherwood.

In January 1939 the two of them left England for the United States, where

Auden became a citizen in 1946. His later works include The Age of Anxiety,

Nones, The Shield of Achilles and Homage to Clio, and he also wrote texts

for works by Benjamin Britten and (with Chester Kallman) the libretto for

Stravinsky's opera The Rake's Progress. Elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford

in 1956, he died in Vienna in 1973.

Nobody

in the thirties was quite sure what war would be like, whether there would

be gas, for instance, or aerial bombardment. There's a stock and rather a

silly question: 'Why was there no poetry written in the Second World War?'

One answer is that there was, but it was written in the ten years before

the war started.

Auden was a landscape poet, though of a rather particular kind. The son of a doctor, he was born in York in 1907 but brought up in Solihull in the heart of the industrial Midlands. Not the landscape of conventional poetic inspiration but, for Auden, magical: from Letter to Lord Byron

But let me say

before it has to go, It's the most lovely country that I know; Clearer than Scafell Pike, my heart has stamped on The view from Birmingham to Wolverhampton. Long, long ago, when I was only four, Going towards my grandmother, the line Passed through a coal-field. From the corridor I watched it pass with envy, thought 'How fine! Oh how I wish that situation mine.' Tramlines and slagheaps, pieces of machinery, That was, and still is, my ideal scenery. At Oxford, he was already writing and

publishing poetry. To his contemporaries, he was a magnetic figure, partly

because he seemed to have all the answers, a characteristic that his later

self came to deplore, though he remained a bit of an intellectual bully all

his life. As a man, he was insecure and unhappy and doesn't seem to have

fallen in love until he went to America in 1939, but this didn't stop him

prescribing for the love affairs of his friends. The Danish philosopher Kierkegaard

says that there are two ways: one is to suffer; the other is to become a

professor of the fact that another suffers. Auden was to play both roles

in His time; but when he was an undergraduate, he was undoubtedly a professor.

Who's Who How Father beat him, how he ran away, What were the struggles of his youth, what acts Made him the greatest figure of his day: Of how he fought, fished, hunted, worked all night, Though giddy, climbed new mountains; named a sea: Some of the last researchers even write Love made him weep his pints like you and me. With all his honours on, he sighed for one Who, say astonished critics, lived at home; Did little jobs about the house with skill And nothing else; could whistle; would sit still Or potter round the garden; answered some Of his-long marvellous letters but kept none. Auden taught at various prep schools in the early thirties, and one of the criticisms that contemporaries made of his poetry was that his view of the world was dictated by his unhappy experiences at school. The best reason I have for opposing Fascism', he said, 'is that at school I lived in a Fascist state.' Not a statement that would commend itself to someone actually having to live in a Fascist state, and the kind of remark that made him blush once he got away from England in 19.39. 'All the verse I wrote,' Auden said later, all the positions I took in the thirties didn't save a single Jew. These writings, these attitudes only help oneself They merely make people who think like one admire and like one, which is rather embarrassing. Which is true, but which says nothing about the poetry, and embarrassing though the older Auden found his younger self, the poetry of that younger self survives the embarrassment. The turning point in Auden's life came, or is supposed to have come, when he and Isherwood went to the Umted States at the start of 1939 and stayed there, both eventually becoming American citizens. Silly people at the time took this to be cowardice, which it wasn't, and even people who admired him thought Auden's poetry was never as good afterwards. But this wasn't true either. Why Auden left England has been much discussed. Auden liked feeling at home, but he didn't like feeling at home where he felt at home. England was too cosy. He would never grow up there, he thought. He would always be the enfant terrible, the prisoner of his public and court poet to the Left. At least this is how Auden came to see it. But it wasn't quite like that either. All that had happened was that he had gone to America in 1939, seemingly with no plans to stay, and, for the first time in his life, he had fallen in love - with Chester Kallman, with whom he was to live happily and unhappily for the rest of his life. It just happened that change in private places went with change in public places, love and war coinciding: Auden really was just an early 'GI bride'. Somebody who cared more about what people thought would have come back when war started, but Auden - and it was one of the winning characteristics in a personality that was not always attractive - didn't care tuppence what people thought. As it transpired, going to America turned out to be a deliverance, the kind of escape an established writer often craves, a way of eluding his public, of not having to go on writing in the same way, of not having to imitate himself 'By the time you have perfected any style of writing', said George Orwell, 'you have always outgrown it.' 'You spend twenty-five years learning to be yourself,' said Auden, 'and then you find you must now start learning not to be yourself - and it took him a while. This next poem Auden called a 'hangover from home'. He wrote it in America, but one of the reasons he left England, he said, was to stop writing poetry like this.

|