|

Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938)

Osip Emilievich Mandelstam was born in Warsaw to a Polish

Jewish family; his father was a leather merchant, his mother a piano

teacher. Soon after Osip's birth the family moved to St Petersburg.

After attending the prestigious Tenishev School, Mandelstam studied

for a year in Paris at the Sorbonne, and then for a year in Germany

at the University of Heidelberg. In 1911, wanting to enter St Petersburg

University - which had a quota on Jews - he converted to Christianity;

like many others who converted during these years, he chose Methodism

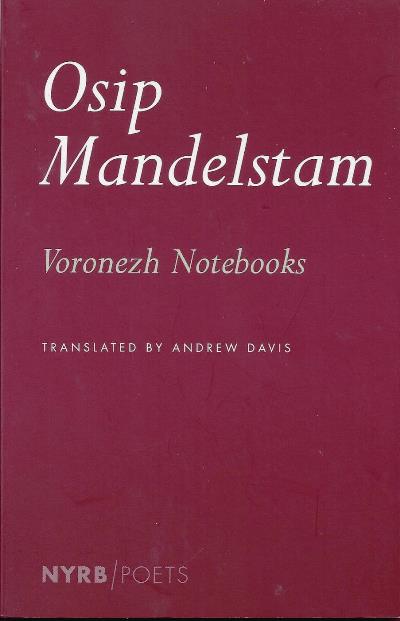

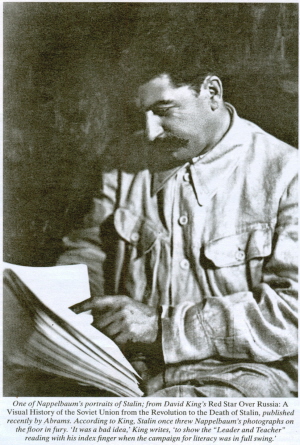

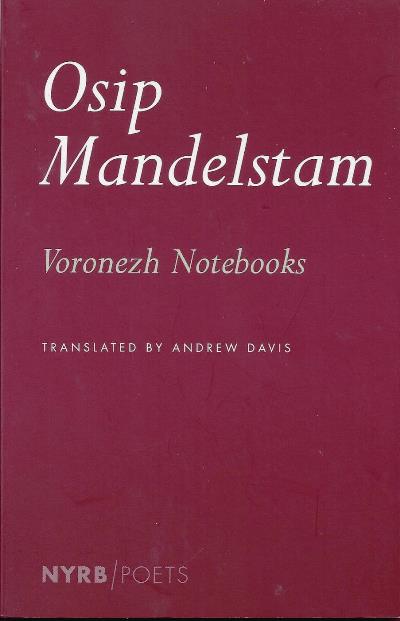

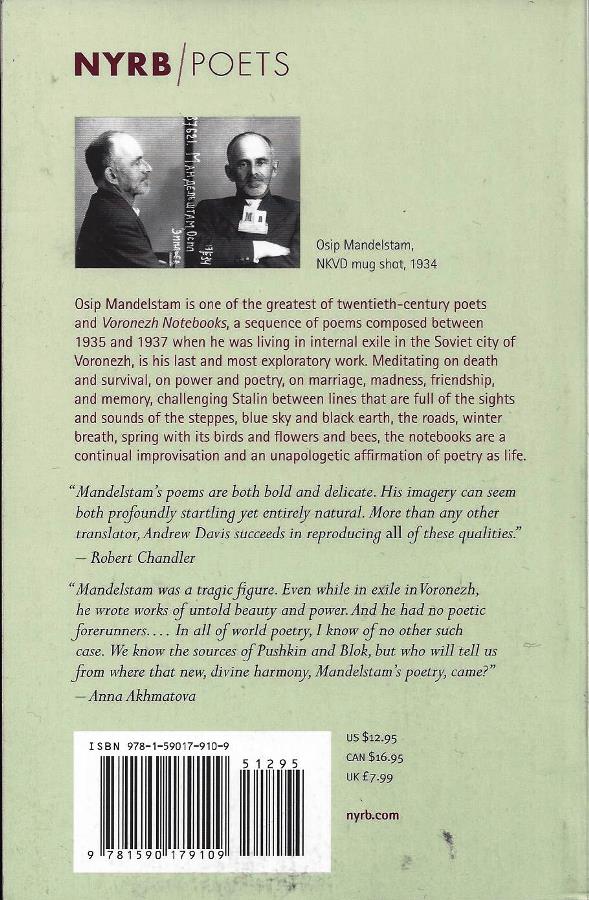

rather than Orthodoxy. [in The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry] Under the leadership of Nikolay Gumilyov, Mandelstam and several other young poets formed a movement known first as the Poets' Guild and then as the Acmeists. Mandelstam wrote a manifesto, 'The Morning of Acmeism' (written in 1913, but published only in 1919). Like Ezra Pound and the Imagists, the Acmeists valued clarity, concision and craftsmanship. In 1913 Mandelstam published his first collection, Stone. This includes several poems about architecture, which would remain one of his central themes. A poem about the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris ends with the declaration: Fortress Notre-Dame, the more attentively I studied your stupendous ribcage, the more I kept repeating: in time I too will craft beauty from sullen weight. In its acknowledgement of earthly gravity and its homage to the anonymous masons of the past, the poem is typically Acmeist. Mandelstam was also a great love poet. Several women - each an important figure in her own right - were crucial to his life and work. An affair with Marina Tsvetaeva inspired many of his poems about Moscow. His friendship with Anna Akhmatova helped him withstand the persecution he suffered during the 1930s. He had intense affairs with the singer Olga Vaksel and the poet Maria Petrovykh. Most important of all was Nadezhda Khazina, whom he married in 1922. Osip and Nadezhda Mandelstam moved to Moscow soon after this. Mandelstam's second book, Tristia, published later in I922, contains his most eloquent poetry; the tone is similar to that of Yeats's 'Sailing to Byzantium' or some of Pound's first Cantos. Several poems were inspired by the Crimea, where Mandelstam had stayed as a guest of Maximilian Voloshin. Once a Greek colony, the Crimea was for Mandelstam a link to the classical world he loved; above all, it granted him a sense of kinship with Ovid, who had also lived by the Black Sea. It was while exiled to what is now Romania that Ovid had composed his own Tristia. The final section of Mandelstam's 1928 volume Poems (the last collection he was able to publish in his life) is titled 'Poems 1921-25'. These twenty poems differ from any of his previous work. Many are unrhymed, and they are composed in lines and stanzas of varying length. This formal disintegration reflects a sense of crisis that Mandelstam expresses most clearly in 'The Age': Buds will swell just as in the past, sprouts of green will spurt and rage, but your backbone has been smashed, my grand and pitiful age. And so, with a meaningless smile, you glance back, cruel and weak, like a beast once quick and agile, at the prints of your own feet. For several years from I925 Mandelstam abandoned poetry or, as he saw it, was abandoned by poetry. Alienated from himself and the world around him, he supported himself by translating. He also wrote memoirs, literary criticism and experimental prose. What helped Mandelstam to recover was a journey to Armenia from May to November 1930. The self-doubt of 'Poems 1921-25' yields to an almost joyful acceptance of tragedy. Armenia's importance to Mandelstam is not surprising: it is a country of stone, and one of the arts in which Armenians have long excelled is architecture. And to Mandelstam Armenia represented the Hellenistic and Christian world where he felt his roots lay; there are ruins of Hellenistic temples not far from Yerevan and it was on Mount Ararat - which dominates the city's skyline - that Noah's Ark is believed to have come to rest. Mandelstam drew strength from a world that felt more solid, and more honest, than the Russia where he had become an outcast. In the autumn of 1933 Mandelstam composed an epigram about Stalin, then read it aloud at several small gatherings in Moscow. It ends: Horseshoe-heavy, he hurls his decrees low and high: in the groin, in the forehead, the eyebrow, the eye. Executions are what he likes best. Broad is the highlander's chest. (trans. Alexandra Berlina) Six months later Mandelstam was arrested. Instead of being shot, he was exiled to the northern Urals; the probable reason for this relative leniency is that Stalin, concerned about his own place in the history of Russian literature, took a personal interest in Mandelstam's case. After Mandelstam attempted suicide, his sentence was commuted to banishment from Russia's largest cities. Mandelstam and his wife settled in Voronezh. There, sensing he did not have long to live, Mandelstam wrote the poems that make up the three Voronezh Notebooks. Dense with wordplay yet intensely lyrical, these are hard to translate. A leitmotif of the second notebook is the syllable 'os'. This means either 'axis' or 'of wasps' - and it is the first syllable of both Mandelstam's and Stalin's first names ('Osip' and 'Iosif' are, to a Russian ear, just different spellings of a single name). In the hope of saving his own life, Mandelstam was then composing an Ode to Stalin," he evidently imagined an axis connecting himself - the great poet - and Stalin - the great leader. In May 1938 Mandelstam was arrested a second time and sentenced to five years in the Gulag. He died in a transit camp near Vladivostok on 27 December 1938. His widow Nadezhda preserved most of his unpublished work and also wrote two memoirs, published in English as Hope Against Hope and Hope Abandoned. Note: A leitmotif of the second notebook is the syllable 'os'. This means either 'axis' or 'of wasps' - and it is the first syllable of both Mandelstam's and Stalin's first names ('Osip' and 'Iosif' are, to a Russian ear, just different spellings of a single name). Tên - first name -của Osip Mandelstam và của Xì, đọc như nhau, trong tiếng Nga. Khi Osip làm bài Ode to Stalin, để vinh danh Xì, tất nhiên, để cứu mạng mình, nhưng thi sĩ tưởng tượng mình "cũng như Xì", the great poet vs the great leader!

8

It's true, I lie in the earth, moving my lips, But what I say will be learned in every school: The round earth is rounder in Red Square, And its slope asserts itself, willingly, The round earth is rounder in Red Square, And its slope is vast, unexpectedly Sloping down-to fields of rice- As long as one last slave is left alive. May 1935 Osip Mandelstam: Voronezh Notebooks Đúng như thế đấy, tớ nằm trong lòng đất, mấp máy môi Nhưng những gì tớ phán thì sẽ được học trong mọi ngôi trường Trái đất tròn, tròn hơn, ở Công Trường Đỏ Và đường cong của nó, khẳng định chính nó, rất ư là hài lòng Trái đất tròn, tròn hơn ở Công Truờng Đỏ Và đường cong của nó rộng rãi, thênh thang, rất ư là không ngờ Đường cong trải dài mãi ra, tới đồng, tới ruộng Trải dài mãi Cho đến khi tên nô lệ cuối cùng, còn lại.

Ta không muốn, như một cánh

bướm trắng kia,

Trả lại mặt đất chút tro than vay mượn. Ta muốn cái thân xác này Biến thành ngã tư, ngã năm, ngã bẩy, Thành phố, thành đường.... Hãy học cùng với Mandelstam, nghệ thuật khó khăn: Lắng Nghe Tiếng Thời Gian. [Như học cùng Phùng Cung: Lắng Nghe Mới Rõ Tiếng Tóc Mình Chuyển Bạc] Nilkiata Struve (Tựa "Tiếng Thời Gian", tập thơ xuôi của nhà thơ Nga Ossip E. Mandelstam) "Pour moi, pour moi, pour moi dit la révolution" "Tout seul, tout seul, tout seul répond le monde" On vivait mieux auparavant, A vrai dire, on ne peut comaprer Comme le sang bruissait alors Et comme il bruit maintenant. Mandelstam

Osip

Mandelstam

Intro 76 A living being is incomparable; don't compare. With a sort of tender fear I embraced the plain's monotony, The circle of the sky my enemy. I appealed to my servant, the air, Waited for its favors, fresh rumors, Gathered for a journey, floated in an arc Of journeys that refused to start ... I'm ready to wander where my sky is greater, But a limpid sadness will not let me leave The still raw hills of Vor6nezh For the clearing, all-human hills of Tuscany. March 16, 1937 77 Rome Where the frogs of the fountains croaked And splashed, they sleep no more. Once wakened, overcome with weeping, With all the power of their throats and shells They water the city, toady to The mighty, with amphibious tears- Summery, cheeky, a light antiquity, With fallen arches and a glance of avidity, Like the untouched bridge of Sant' Angelo Flatfoot over the yellow flow- Light blue, unformed, ashen, In a tumor of houses like a drum, The city's a swallow, made into a dome, A cupola of paths and drafts- You've turned it into a murder-nursery, You-you brown-blood mercenaries- Italian Blackshirts- Vicious whelps of departed Caesars ... They're all your orphans, Michelangelo, Shrouded in marble and shame: The night soaked in tears and the Fleet young David, faultless, And the bed on which Moses Lies like a cataract, without motion- Freedom of power and a lion's portion Fall silent in slavery and sleep. Yieldings of the furrowed stairs, Of flights of rivers flowing to the square: Let those steps ring out like deeds, Let the somnolent citizens of Rome arise, But not for crippled joys like these, Like idle sponges of the sea. The pits of the Forum are dug up anew, And Herod's Gate opened at last- And over Rome hangs the heavy jaw Of the dictator-outcast. March 16, 1937 Osip Mandelstam LENINGRAD I've come back to my city. These

are my own old tears, So you're back. Open wide. Swallow Open your eyes. Do you know

this December day, Petersburg! I don't want to

die yet! Petersburg! I've still got the

addresses: I live on back stairs, and the

bell, And I wait till morning for

guests that I love, Leningrad. December 1930 1972, translated with Clarence

Brown I returned to my city, familiar

to tears, You have returned here-then

swallow Recognize now the day of December

fog Petersburg, I do not want to

die yet Petersburg, I still have addresses

at which I live on a black stair, and

into my temple And all night long I await the

dear guests, [Osip Mandelstam, Selected Poems, translated by David McDuff.

Cambridge: River Press, 1973, p.111] (1) Tôi trở

lại thành phố của tôi, thân quen với những dòng

lệ, Hãy nhận

ra bây giờ ngày tháng Chạp mù sương...

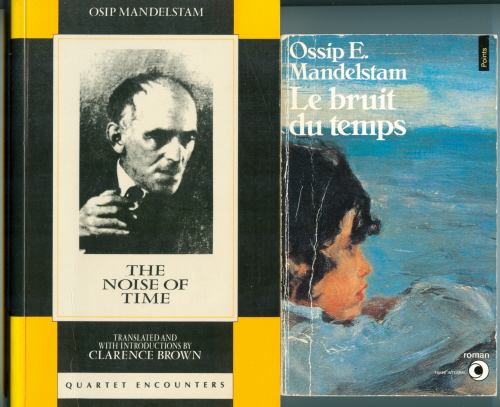

Trong The Noise of Time, Tiếng động của thời gian, lời giới thiệu, có một giai thoại thật thú vị liên quan tới Pasternak, vụ bắt nhà thơ Osip Mandelstam và một cú phôn của Bác Xì, từ Điện Cẩm Linh. Liền sau khi Osip bị bắt, nhà

thơ được Stalin đích thân hỏi tội. Đây là

một đặc ân chưa từng một nhà thơ nào được hưởng,

do quyền uy của nhà thơ [perhaps the profoundest tribute ever paid

by the Soviet regime to the power of Mandelstam’s pen]. Do chính

Boris Pasternak kể lại. -Phải Pạt đó không?

Đây là Xì ta lìn. Chói lọi mới chẳng trói

lại!

8

It's true, I lie in the earth, moving

my lips,

INTRODUCTION But what I say will be learned in every school: The round earth is rounder in Red Square, And its slope asserts itself, willingly, The round earth is rounder in Red Square, And its slope is vast, unexpectedly Sloping down-to fields of rice- As long as one last slave is left alive. May 1935 Osip Mandelstam: Voronezh Notebooks Đúng như thế đấy, tớ nằm trong lòng đất, mấp máy môi Nhưng những gì tớ phán thì sẽ được học trong mọi ngôi trường Trái đất tròn, tròn hơn, ở Công Trường Đỏ Và đường cong của nó, khẳng định chính nó, rất ư là hài lòng Trái đất tròn, tròn hơn ở Công Truờng Đỏ Và đường cong của nó rộng rãi, thênh thang, rất ư là không ngờ Đường cong trải dài mãi ra, tới đồng, tới ruộng Trải dài mãi Cho đến khi tên nô lệ cuối cùng, còn lại. W. H. AUDEN once complained to Joseph Brodsky: "I. don't see why Mandelstam is considered a great poet. The translations that I've seen don't convince me at all"*-a comment that indicates the conflict between Osip Mandelstam's reputation as one of the greatest poets of the twentieth century and his equally notorious impermeability to translation, if not to comprehension itself. Why is Mandelstam so hard to get at? There is, of course, the density of his language and imagery and the prominent role of rhyme and rhythm in his work. He was one of the great “orchestrators" of language, one of the great masters of sound and cadence, which has posed enormous-some would say insuperable-obstacles to translation. Related is the tantalizing, and perennial, question of the differences between Russian and English poetic practice, a question whose scope and complexity is beyond my capacity to deal with here. But underlying everything, I think, is the * Joseph Brodsky, "The Child of Civilization," in Less Than One: Selected Essays (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1987), 142. unique, the radical demand that Mandelstam places on his readers. All of Mandelstam's poetry is excavated from the midden of his experience. This is its fundamental, invariable, characteristic, and essential principle. There was little of the theoretician and nothing of the mystic in him; he was the most earthly of men. One can see this clearly in the highly unusual way he treats three common poetic images, both in the Voronezh Notebooks and in his earlier poetry, images through which he expressed his horror at being separated from life. Not just by death-though death was a real threat when he was composing the Notebooks -by any-thing that prevented him from immersing himself in physical, palpable existence. For Mandelstam, the sky (nebo) most often suggested not some paradise or heaven but sexless, inhuman, asphyxiating emptiness. The appearance of stars in his poetry indicated, as his wife, Nadezhda, pointed out, not a movement toward the eternal but the shrinking away from the essentially human and, therefore, the coming to an end of the poetic impulse. And air (vozduhk)-or rather the lack of it, one of Mandelstam's greatest preoccupations in the Notebooks-stood in not as an animating principle, not as some cipher for the soul, but as an earthly element. It represented the most insistent of the triad of life's physical necessities-food, water, breath-and by extension the freedom to move in a physical world..

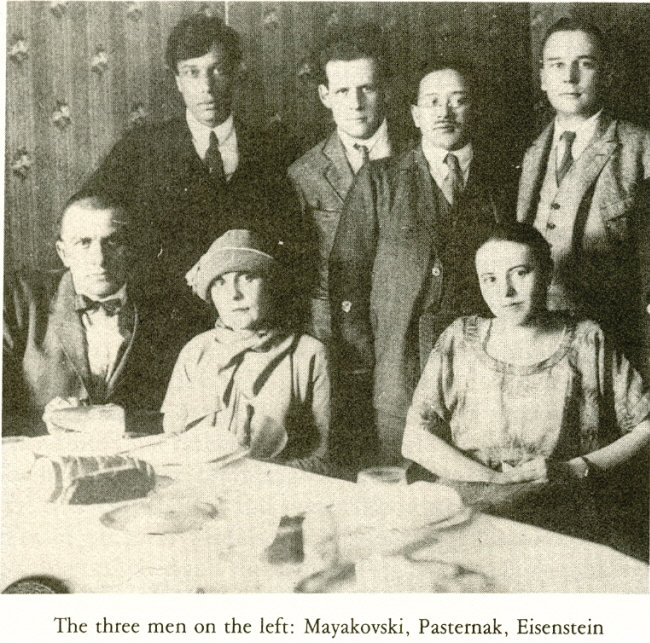

Looking on a Russian Photograph, 1928/1995

It's the classic picture of doom.

Three great poets stand together in 1928, the Revolution just a decade old,

their hearts and brains soon to be dashed out on the rocks of Russian fascism,

the flower of their achievements destined to be crushed by the new czar,

Stalin. The Paris Review Winter 1995: Russian Portraits Quái đản thật. Ở cái

xứ VC Niên Xô này, ngay cả những tay theo

Đảng, phò Đảng thì cũng bảnh, cực bảnh, như bộ ba

trên đây. Ở cái xứ Bắc Kít, toàn Kít! Một bức hình

cổ điển về đọa đầy, trầm luân, bất hạnh…Ba nhà thơ

lớn chụp chung với nhau vào năm 1928, Cách Mạng thì

mới được 10 tuổi, tim và óc của họ sẽ nát bấy

ra trên những hòn đá của phát xít

Nga, bông hoa thành tựu sẽ bị nghiền nát dưới gót

giầy của sa hoàng mới của Nga – Stalin. Eisenstein, Mayakovski, Pasternak

- mỗi người một cái chết,

mỗi người một cuộc tra tấn riêng. Mayakovski, bị cự tuyệt

trong tình yêu, bị cầm tù tại Moscow, tự sát

vào năm 1930, ở tuổi đời 36. Trái tim bể của Eisenstein

ngưng đập vào năm 1948, những đồ án nâng niu bị

phản bội, nhà làm phim 53 tuổi bị truy đuổi bách

hại khi ở hải ngoại, bị canh trừng chặt chẽ khi ở nhà. Pasternak, đã

từ lâu bị nhà cầm quyền của ông chối từ, sau

cùng sống sót chế độ Stalin – tuy nhiên khi

tuyệt tác của ông Bác

Sĩ Zhivago được trao Nobel, ông không được phép

đi nhận giải, sách bị đốt, tên bị trà đạp bôi

nhọ ở quê nhà. Nhưng, như bức

hình cho thấy, ba nhà thơ đứng hiên ngang,

vào năm 1928, ba trái tim trẻ, can đảm, đông

lạnh trong chiến thắng, những biểu tượng sau cùng của 1 nền

văn minh trước khi khùng điên, ba trợn. Tuy nhiên,

riêng tôi, thì lại nhận ra 1 điều, họ mới hạnh

phúc, may mắn biết bao, khi cả ba có thể kinh nghiệm những

cuộc khủng hoảng lớn, và chọn lựa lớn.

Làm sao Ông đã làm sao... Tố Hữu Vào tháng 11 năm 1933,

Osip Mandelstam sáng tác bài thơ trứ danh

“Vịnh Stalin”, ‘người leo núi Cẩm Linh’, ‘kẻ sát

nhân tên làm thịt dân quê’. Tháng

Năm 1934, ông bị bắt vì tội 'phản cách mạng',

bị tra hỏi trong 2 tuần, nhưng lạ lùng làm sao, do lệnh

trên ban xuống, không bị làm thịt hay bỏ tù,

mà chỉ bị ‘cách ly nhưng đừng để chết’. Hai vợ chồng trải

qua 3 năm lưu vong ra khỏi những thành phố lớn; khi trở về, sống

giữa đám bạn bè lòng vòng ở Moscow. Tháng

Năm 1938, ông chồng bị bắt trở lại, kết án 5 năm tù,

và lần này bị đầy đi Vladivostok, chỉ kịp gửi một cái

note, cho ông em/anh, gửi ‘quần áo sạch’; ông không

thoát được mùa đông tại đó. Bà vợ

sống dai hơn ông chồng 42 năm, nhẩn nha nhớ lại thơ chồng. Chúng

ta được biết những chi tiết hiếm quí đó là qua

hồi ký tuyệt vời của bà vợ, “Hy vọng chống lại hy vọng” Có 2 cách đọc Nguyễn

Tuân? 1. Tình cờ ghé Blog

của me- xừ Đông B, ông ta gọi cái món

này là 'mặc cảm dòng chính'! Câu ấy ai cũng nói. Nhưng nó

theo cả đời rồi. Mình phải cầm đóm lấy mới ngon.

Để người châm hộ không ngon. You

invented me. No such person exists, that's for sure,

There's no such creature anywhere in sight. No poet can quench my thirst, no physician has a cure, The shadow of your ghost haunts me day and night. We met in an unbelievable year, The energies of the world were worn through, The world was in mourning, everything sagged with fear, And only the graves were new. In the absence of light, how black the Neva grew, The deaf night surrounded us like a wall . . . That's exactly when I called out to you! What I was doing-I didn't yet understand at all. And, as if led by a star you came to me, As if walking on a carpet the tragic autumn had grown, Into that house ravaged for the rest of eternity, From whence a flock of burned verses has flown. 1956 Mi phịa ra ta. Làm gì có cô gái nào tên là BHD, chắc chắn như thế, Làm gì có thứ bông hoa lạ như thế ở khắp mọi nơi, trong tầm nhìn Chẳng tên thi sĩ nào có thể làm dịu cơn khát của ta, không tên y sĩ nào có thứ thần dược chữa trị, Cái bóng của con ma tình, là mi, tên GCC, làm khổ ta ngày và đêm Hai đứa ta gặp nhau đúng trong cái năm không thể nào tin tưởng được đó Nhiệt tình trọn thế gian đốt trọn cuốn lịch Thế giới ư, tóc tang tang tóc, mọi chuyện chùng xuống vì sợ hãi Chỉ những nấm mồ là mới. Thiếu vắng ánh sáng, con sông Neva bèn càng đen thui Đêm điếc đặc bao quanh đôi ta như bức tường Đúng là vào lúc như thế ta gào tên mi, GCC! Ta đang làm gì đây - Ta chẳng thể nào hiểu Và, như thể được 1 vì sao dẫn dắt, Mi bèn đến với ta.... Selected and Translated by Lyn Coffin OSIP MANDELSTAM

I

July 28, 1957

AND LOZINSKY'S DEATH SOMEHOW broke the thread of my reminiscences. I no longer dare to recall things that he cannot corroborate (about the Poets' Guild, Acmeism, the journal The Hyperborean, and so forth). In recent years we rarely saw each other because of his illness and I didn't get a chance to have a real talk with him about some important matters or to read him my poems from the 1930s (Requiem). Probably that accounts for the fact that he continued to think of me to some degree as the same poet he had known long ago in Tsarskoe Selo. This became clear when we were both reading the proofs of my collection From Six Books in 1940. * * *

Something similar happened

with Mandelstam, who of course knew all my poems,

but in a different way. He did not know how to reminisce

rather it was a different sort of process for him that I don't

have a name for now, but something doubtless akin to creativity.

(For example, Petersburg in The

Noise of Time seen through the bright eyes of a five-year-old

boy.) Mandelstam was one of the most brilliant conversationalists.

He didn't just listen to himself and answer himself, which is what almost

everyone does nowadays. In conversation he was polite, quick to react,

and always original. I never heard him repeat himself or "play the same

old record”. He learned foreign language with unusual ease

http://www.tanvien.net/Tribute_1/Mandelstam.html

Osip

Mandelstam

21 Not as a butterfly, white as flour, Will I return to the earth my borrowed dust- I want my body, intelligent form, In street and country to be transformed: Vertebrate body, charred to ash, Conscious of its own specific size. Cries of dark green needles of the pines, Pine wreathes from the depths of wells Extend our lives and precious time, Support themselves on death machines- Red-banner hoops made out of boughs, Enormous, elementary wreaths! Comrades of the final call-up rose To labor in the leaden skies, In silence the infantry passed by, Their shouldered arms like exclamations. And a thousand antiaircraft guns- Their pupils either brown or blue- Straggled in disorder-men, men, men- And who'll come after them? July 21, 1935-May 30, 1936 OSIP MANDELSTAM

I

July 28, 1957

AND LOZINSKY'S2 DEATH SOMEHOW broke the thread of my reminiscences. I no longer dare to recall things that he cannot corroborate (about the Poets' Guild, Acmeism, the journal The Hyperborean, and so forth). In recent years we rarely saw each other because of his illness and I didn't get a chance to have a real talk with him about some important matters or to read him my poems from the 1930s (Requiem). Probably that accounts for the fact that he continued to think of me to some degree as the same poet he had known long ago in Tsarskoe Selo. This became clear when we were both reading the proofs of my collection From Six Books in 1940. * * *

Something similar happened with Mandelstam, who of course knew all

my poems, but in a different way. He did not know how to reminisce rather

it was a different sort of process for him that I don't have a name for

now, but something doubtless akin to creativity. (For example, Petersburg

in The Noise of Time seen through the bright eyes of

a five-year-old boy.) Mandelstam was one of the most brilliant conversationalists.

He didn't just listen to himself and answer himself, which is what almost

everyone does nowadays. In conversation he was polite, quick to react,

and always original. I never heard him repeat himself or "play the same

old record”. He learned foreign language with unusual ease

To Osip Mandelstam

Nothing's been taken away! We're apart -I'm delighted by this! Across the hundreds of miles that divide us, I send you my kiss. Our gifts, I know, are unequal. For the first time my voice is still. What, my young Derzhavin, do You make of my doggerel? For your terrible flight I baptize you - young eagle, it's time to take wing! You endured the sun without blinking, but my gaze - that's a different thing! None ever watched your departure more tenderly than this or more finally. Across hundreds of summers, I send you my kiss. MARINA TSVETAEVA (1916) Peter Oram Gửi Osip Mandelstam

Chẳng có gì bị lấy đi Đôi ta mỗi người mỗi ngả - Em sướng điên lên vì chuyện này! Qua ngàn dâu xanh biếc một màu, em gửi tới chàng 1 nụ hôn Tài năng thiên bẩm của đôi ta, thì không đồng đều Lần đầu tiên, tiếng nói của ta câm nín Hỡi anh yêu, tên tuổi trẻ Derzhavin của ta ơi Mi đã làm gì với những vần thơ tồi tệ của ta? Dành cho chuyến đi khủng khiếp của mi Tới đây, ta rửa tội cho – Con chim ưng trẻ, tới giờ cất cánh Hãy nhìn thẳng vào mặt trời, chịu đựng chuyến bay, không thèm nháy mắt Nhưng cái nhìn ban phước lành của ta cho mi, thì lại là chuyện khác Chẳng đứa khốn nào theo dõi mi lên đường Dịu dàng như thế này Sau chót như thế này Qua ngàn ngàn mặt trời, ánh nắng, mùa hè Ta gửi cho mi nụ hôn của ta http://www.tanvien.net/new_daily_poetry/29.html Bữa trước Tin Văn có nhắc tới nhà thơ Mẽo Robert Hass. Ông này chê thơ Osip Mandelstam, chúng ta lòa con mắt vì sự tuẫn nạn của ông, chứ thơ có ghê gớm chi đâu! Hóa ra không chỉ Hass, mà Auden, cũng đếch chịu nổi thơ Osip! Mới vớ được tập thơ thần sầu của ông. Quả là quá cả thơ hũ nút của TTT.

LMH giới thiệu Phùng Cung

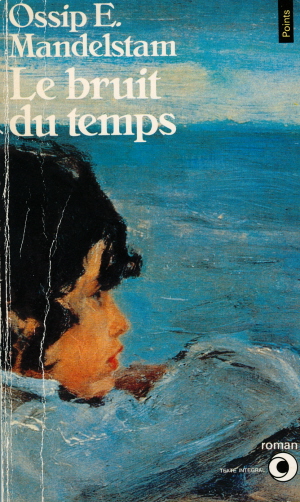

Le Bruit Du Temps

Trong gối vọng tiếng ru Phùng Cung En me privant des mers, de l'élan,

de l'envol Mandelstam [Mi lấy của ta Nhà thơ biết rằng mặc

dù sự cô đơn, tủi nhục, tiếng môi run sẽ có

một ngày nghe được, Ta không muốn, như một

cánh bướm trắng kia, Hãy học cùng với

Mandelstam, nghệ thuật khó khăn: Nilkiata Struve Lời Tựa "Tiếng Thời Gian" "Pour moi, pour moi, pour moi

dit la révolution" On vivait mieux auparavant, Akhmatova: Nửa Thế Kỷ Của Tôi Robert Hass, trong bài

viết “gia đình và nhà tù, families and prisons”

in trong “What light can do”, nhắc tới Mandelstam, ông cảm thấy

khó chịu, về cái sự bị hớp hồn của chúng ta đối

với nhà thơ, vì vài lý do, but I am uneasy

by our fascination with him for a couple of reasons. Đẩy quá lên bước nữa, có thứ văn chương chúng ta đếch cần đọc, vì chẳng bao giờ nó ngó ngàng đến cái độc, cái ác của con người, nhất là Cái Ác Á Châu, trong có Mít. |