|

Kỳ vương ra đi

Đứa nào cũng muốn

làm thịt kỳ vương, "Đả biến thiên hạ vô địch thủ, Kim Diện Phật, Miêu

Nhân Phượng" [Đánh khắp thiên hạ, chẳng kiếm ra địch thủ, ông Phật mặt

vàng, Miêu Nhân Phượng]. Và kỳ vương thì lúc nào cũng sẵn sàng chờ đám

khốn kiếp. Trong chiếc cà tạp có khóa, là đủ thứ kỳ hoa dị thảo, được

Độc Thủ Dược Vương, sư phụ Trình Linh Tố ban cho, dùng để trị độc,

phòng khi tụi khốn bỏ vô đồ ăn. Riêng về bộ cẩm nang kỳ, thư từ, hình

ảnh, trong có cả của Tổng Thống Nixon, được cất giữ trong một cái két

sắt hai lần khoá, tại California.

Và ngay cả khi kỳ vương toan tính xuất hiện, trong những chương trình radio, tại Hungary, hay tại Phi Luật Tân, vô ích, chẳng có gì đem lại an toàn cho kỳ vương, đối với đám Nga xô, hay Do Thái, hay "chuột Xịa làm việc cho Do Thái". Nhưng, kỳ vương vẫn cố thử thời vận của mình. Chúng cố phá hoại luôn cả cuộc chơi. Và trong lần tranh chức vô địch, với địch thủ Nga xô, Boris Spassky, tại cuộc Hoa Sơn luận kỳ, 1972, tại Reykjavik, chúng kiếm đủ mọi cách làm nhiễu, chia trí kỳ vương, nào camera TV để ngay kế bên vai, nào bàn chơi sáng quá, nào trò phản chiếu ánh sáng, nào ho, nào hắng, khiến ông phải yêu cầu bỏ trống 7 hàng ghế đầu, khán thính giả. Và trong khi địch thủ Nga phải cầu cứu tới 35 đại sư phụ, trong lịch sử cờ vua của nước này, ông vẫn chỉ trông cậy, vào cái đầu độc nhất của mình, một cái đầu thê thảm và thông minh [his own long, lugubrious, clever head], và cuốn sổ ghi. Và ông thắng. Đúng như thế đấy. Anh hùng Cuộc Chiến Lạnh. Một anh chàng kỳ kỳ, the quirky individual, cho cả một guồng máy nhà nước, đi chỗ khác chơi. Mẽo làm thịt [thrash: nện] Liên Xô, ngay trong trò chơi "quốc hồn quốc túy", niềm tự hào, của nó! Nhưng Mr. Fischer, trong những bộ đồ lịch sự, và thiên tài trẻ thơ của mình, đả biến thiên hạ vô địch thủ, quán quân cờ từ khi 15 tuổi, và trận thắng kinh thiên động địa, 20-game, đợt 1968-71, vẫn luôn chỉ là một cậu bé ngờ ngệch, do dự, chẳng có gì là dứt khoát, trên tấm biển quảng cáo, an unsettling poster-boy. Mục đích của tôi, ông nói với mọi người, không chỉ là, thắng, nhưng mà là, quần cho cái đầu của địch thủ mê tơi, rồi, "em" đã biết tay anh chưa? [It was to crush the other man's mind until he squirned]. Và, trong cái phong cách hơi bị tư bản hoá, trở thành giầu có. Chính ông đã nài nỉ, đòi cho bằng được, và thế là giải thưởng vô địch được tăng lên, từ $1,400 thành $250,000. Tuyệt! Và, trong trận tái đấu với me-xừ Nga xô, Mr. Spassky, vào năm 1992, ông bỏ túi $3.5m. Tuyệt! * Kỳ vương Nga

tưởng niệm kỳ vương Mẽo

The Chessman At Fischer's

peak, even his adversaries had to admire his game.

Khi mà Fischer ở trên đỉnh, thì địch thủ cũng phải cúi đầu ngưỡng mộ ngón đòn của ông! [Time, 4 Tháng Hai 2008] Hình như Steiner

đi cả một cuốn sách về kỳ vương Fischer và cuộc Hoa Sơn luận cờ giữa

hai phe Đông Tà - Tây Độc? (1)

* (1) FIELDS OF FORCE [Những trường của lực], by

GEORGE STEINER 86 pages. Viking Press. $8.95.

Time có bài điểm: Critic's Gambit To be sure, Steiner admits, Bobby inoculated the world with chess fever singlehanded. Piling demands upon tantrums, he elevated the first prize from $3,000 to $2 million and transformed a board game into a blood sport. But Steiner, a literary critic first and a chess patzer second, is appalled by Fischer's xenophobic rancor, his avarice and below all, his literary taste (Fu Manchu, Tarzan and Playboy). * Fields of Force: Fischer and Spassky at Reykjavik (1974) * Vua cờ ra đi Kim Dung có nhiều xen, xen nào cũng ly kỳ, về kỳ [cờ]. Ván cờ Hư Trúc, khỏi nói. Ván cờ, chưa đánh, chỉ mới vẽ bàn cờ, mà đã mở ra một trường tình trường, và một trường tai kiếp: cuộc gặp gỡ giữa Côn Luân Tam Thánh, trước, với Quách Tường, và sau, với nhà sư già gánh nước đổ vô giếng, trên Thiếu Lâm Tự. Ván cờ thổ huyết mở cõi tù cho Nhậm Ngã Hành... Ván cờ Fischer vs Spassky được coi là ván cờ của thế kỷ. Một trong những yêu cầu của cờ liên quan tới trí nhớ của con người. Và cái sự nhớ đó, cũng rất ly kỳ, mỗi thiên tài có một kiểu nhớ khác nhau. Gấu còn nhớ, có đọc một bài báo, nói về trí nhớ của vua cờ Kasparov. Truớc một trận đấu, ông coi lại một số trận đấu lừng danh trên chốn giang hồ, và bộ não của ông chụp [copy] chúng, khi gặp nước cờ tương tự, là cả bàn cờ lộ ra, cùng với sự thắng bại của nó. Cũng trong bài viết, còn nhắc tới một diễn viên, nhớ, và nhập vai, trong một vở tuồng, xong, là xóa sạch, để nạp cái mới. Ván cờ trên núi Thiếu Thất. Khi hứng cờ nổi lên, Côn Luân Tam Thánh vận nội lực, dùng chỉ lực vẽ bàn cờ, Giác Viễn thiền sư nghĩ tay này muốn so tài, bèn vận nội lực vô bàn chân, đi từng bước, xóa sạch: Cửu Dương thần công lần đầu tiên dương oai. Ván cờ không xẩy ra, nhưng trước đó, Côn Luân Tam Thánh, ngồi buồn, tự vẽ bàn cờ, hai tay là hai địch thử, phân thua thắng bại, Quách Tường đứng ngoài, mách nước, sao không bỏ Trung Nguyên lấy Tây Vực, giang hồ kể như đã phân định. Độc giả say mê Kim Dung và

say mê

môn chơi cờ, chắc khó quên nổi ván cờ của chưởng môn nhân phái Tiêu

Dao. Ván cờ ma quái, chính không ra chính, tà không phải tà. Dùng chính

đạo phá không xong mà theo nẻo tà phá cũng chẳng đặng. Có người ví nó

với thế Quốc Cộng ở một số quốc gia trên thế giới. Sau, Hư Trúc, chẳng

biết chơi cờ nên cũng chẳng màng đến chuyện được thua, cũng chẳng luận

ra đâu là tà, đâu là chính, đi đại một nước chỉ nhằm mục đích nhất thờI

là cứu người, vậy mà giải được. Nước cờ của Hư Trúc, cao thủ đều lắc

đầu vì là một nước cờ tự diệt, nhờ vậy mà tìm ra sinh lộ. Có những nhà văn suốt đời chỉ viết đi viết lại một cuốn sách. Tất cả những tác phẩm lớn của Kafka đều là những cái bóng được phóng lên từ những truyện ngắn, những "ngụ ngôn, ẩn dụ" của ông. *

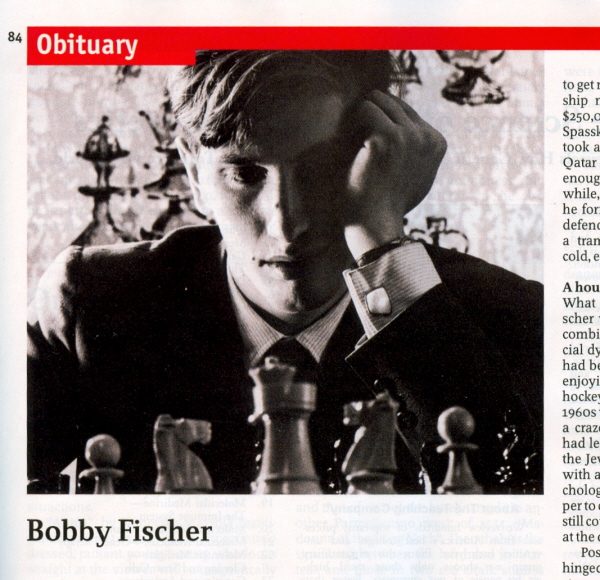

Bobby Fischer, an unsettling chess-player, died on January 17th aged 64 PEOPLE were always coming to get Bobby Fischer. And he was ready for them. In a locked suitcase he kept bottles and bottles of vitamin pills and herbal potions and a large orange-juicer in case they tried to put toxins in his food. His most precious memorabilia-match notebooks, photo albums, letters from President Nixon-were kept in a filing cabinet in a safe behind two combination locks in a ten-by-ten storage room in Pasadena, California. In the end, as he railed to radio talk show hosts in Hungary and the Philippines, even all this couldn't keep him safe from Russians, or Jews, or "CIA rats who work for the Jews". But he had tried. They tried to disrupt his chess games, too. As he wrestled for the world championship against Boris Spassky at Reykjaavik in 1972 they poked whirring TV cameras over his shoulder. They made the board too shiny, reflecting the lights, and fidgeted and coughed until he cleared out the first seven rows of the audience. By the third game he insisted on retreating to a tiny back room, where he could think. He was always better in dingy, womb-like spaces: the cabinet room of the Marshall Chess Club in New York City, where as a boy he skipped school to spend his mornings reading through old file-cards of 19thhcentury games; a particular table in the New York Public Library, where he sat for hours immersed in chess history, openings and strategy; or the walk-up family flat in Brooklyn where, once his mother and sister had moved out, he set up continuous chess games beside each bed, ignoring the outside sunshine to compete against himself. If you could see inside his brain, as his enemies no doubt hoped to, you would find it primed to attack and defend in every way possible, with a straight moving rook or a sidling bishop, or with both in his favorite Ruy Lopez opening, or with the queen swallowing an early pawn in the "poisoned" version of the Sicilian, or a thousand others. At Reykjavik, when Mr. Spassky was advised between games by 35 Russian grand masters, Mr. Fischer had a notebook and his own long, lugubrious, clever head. And he won. That made him a cold-war

hero. The quirky individual had

outplayed the state machine, and America had thrashed the Soviet Union

at its

own favorite game. But Mr. Fischer, for all his elegant suits and

childhood

genius, his grand mastership at 15 and his 2o-game winning streak at

championship level in 1968-71, was always an unsettling poster-boy. His

objective, he told everyone, was not just to win. It was to crush the

other

man's mind until he squirmed. And, in proper capitalist style, to get

rich. At

his insistence, the championship money was raised from $1,400 to

$250,000; from

the rematch with Mr. Spassky in 1992, which he also won, he took away

$3.5m.

Since few venues, even Qatar or Caesar's Palace, offered him enough to

make

public playing worth his while, he spent the years after 1975 (when he

forfeited his world title by refusing to defend it) largely wandering

the world

like a tramp, castigating his enemies. Only cold, eccentric Iceland

welcomed

him. A house like a rook What exactly was wrong with Bobby Fischer was a subject of much debate. The combination of high intelligence and social dysfunction suggested autism; but he had been a normal boy in many respects, enjoying Superman comics and going to hockey games. He had got mixed up in the 1960s with the worldwide Church of God, a crazed millenarian outfit, and perhaps had learned from them to hate and revile the Jews; though he was Jewish himself, with a Jewish mother who had tried psychologists and the columns of the local paper to cure him of too much chess, but who still couldn't stop the pocket set coming out at the dinner table. Possibly-some said-he had been unhinged by the American government's stern pursuit of him after the 1992 rematch, which was played illegally in the former Yugoslavia. He cursed "stinking" America to his death, and welcomed the 2001 terrorist attacks as "wonderful news"-at which much of the good he had done for chess in his country, from inspiring clubs to instructing players to simply making the game, for the first time, cool, drained away like water into sand. Perhaps, in the end, the trouble was this: that chess, as he once said, was life, and there was nothing more. Mr. Fischer was not good at anything else, had not persevered in school, had never done another job, had never married, but had pinned every urgent minute of his existence to 32 pieces and 64 black and white squares. He dreamed of a house in Beverly Hills that would be built in the shape of a rook. Within this landscape, to be sure, he was one of the world's most creative players; no one was more scathing about the dullness of chess games that were simply feats of memorizing tactics. Most world championship games, he claimed, were pre-arranged, proof that the "old chess" was dead, and rotten to the core. He invented a new version, Fischer Random, in which the back pieces were lined up any old how, throwing all that careful book learning to the winds. Yet the grid remained and the rules remained: attack, defend, capture, sacrifice. Win at all costs. From this grid, and from this war, Mr. Fischer could never escape. The Economist 26 Jan, 2008 APPRECIATION The Chessman. Yes, he had deep flaws. But Bobby Fischer should be remembered for his genius BY GARRY KASPAROV IT IS HARD TO SAY EXACTLY when I first heard the name Bobby Fischer, but it was quite early in my life. When he was battling Boris Spas sky for the world title in 1972, I was a 9-year-old club player in my native Baku in the Soviet Union. I followed the games avidly. The newspapers had extensive daily coverage of the match, although that waned as it became clear the Soviet champion was headed for defeat. Fischer's My 60 Memorable Games was one of my first chess books. (It had been translated into Russian and sold in the U.S.S.R. with no respect for copyright or royalties, infuriating its author.) As I improved during the 1970S, my coach, Alexander Nikitin, made charts to track my progress and to set goals for me. A rating above 2500 was grand master; 2600 meant membership in the Top 10; 2700 was world-champion territory. And even above that was Bobby Fischer, at the very top with 2785. I became world champion in 1985, but true to Nikitin's vision, I had an even loftier goal; it took me four full years to surpass Fischer's rating record. It was Fischer's attitude on and off the board that infused his play with unrivaled power. Before Fischer, no one was ready to fight to the death in every game. No one was willing to work around the clock to push chess to a new level. But Fischer was, and he became the detonator of an avalanche of new chess ideas, a revolutionary whose revolution is still in progress. At Fischer's peak, even his adversaries had to admire his game. At the hallowed Moscow Central Chess Club, top Soviet players gathered to analyze Fischer's crushing 1971 match defeat of one of their colleagues, Mark Taimanov. Someone suggested that Taimanov could have gained the upper hand with a queen move, to which David Bronstein, a world-championship challenger in 1951, replied, "Ah, but we don't know what Fischer would have done." Not long afterward, the grim Soviet sports authorities dragged in Taimanov and his Briefing peers to discuss Taimanov's inability to defeat the American. How had he failed? Was he not a worthy representative of the state? Spassky finally spoke up: "When we all lose to Fischer, will we be interrogated here as well?" By World War II, the once strong U.S. chess tradition had largely faded. There was little chess culture, few schools to nurture and train young talent. So for an American player to reach world-championship level in the 1950S required an obsessive degree of personal dedication. Fischer's triumph over the Soviet chess machine, culminating in his 1972 victory over Spassky in Reykjavik, Iceland, demanded even more. Fischer declined to defend his title in 1975, and by forfeit, it passed back into the embrace of the Soviets, in the person of Anatoly Kasparov. According to all accounts, Fischer had descended into isolation and anger after winning that final match game against Spassky. Fischer didn't play again until a brief and disturbing reappearance in 1992, after which his genius never again touched a piece in public. Having conquered the chess Olympus, he was unable to find a new target for his power and passion. I am often asked if I ever met or played Bobby Fischer. The answer is no, I never had that opportunity. But even though he saw me as a member of the evil chess establishment that he felt had robbed and cheated him, I am sorry I never had a chance to thank him personally for what he did for our sport. Much has already been written about Fischer's disappearance and apparent mental instability. Some are quick to place the blame on chess itself for his decline, which would be a foolish blunder. Pushing too hard in any endeavor brings great risk. I prefer to remember his global achievements instead of his inner tragedies. It is with justice that Fischer spent his final days in Iceland, the place of his greatest triumph. There he was always loved and seen in the best possible way: as a chess player Kasparov, author of How Life

Imitates Chess, was the world's

top-ranked player from 1985 until he retired from the game in 2005 Critic's Gambit FIELDS OF FORCE by GEORGE

STEINER 86 pages. Viking Press. $8.95. &

|