|

Hilton Als For Evgenia This happened in 1967. That year, the American author Truman Capote, then forty-three years old, published a beautiful essay he titled "Ghosts in Sunlight." The piece-it's not very long -describes the author's experience on the set of the film adaptation of his 1966 best-selling book, In Cold Blood. At one point Capote relates how the actors impersonating the real-life protagonists in his famous "non-fiction novel" unsettled him, rattled him, for there they were, alive and interpreting the thoughts and feelings of men he had known long before, dead men he could not shake. Capote describes this experience as being akin to watching "ghosts in sunlight"-a lovely metaphor about memory and the real converging to make the world something else, and the artist someone else, too. Standing on

that film set, the Capote who had written In Cold Blood was a relative ghost

to

the film being made; he was a specter standing in the sunlight of his

former

self. I think I understand something about the anxiety Capote expresses

in the

piece; I certainly understand when he relates how, at some point during

his In

Cold Blood process, he'd fall into bed with a bottle of scotch

and pass out, the

victim of a disorienting emotional flu. Nostalgia is one thing, but

making art

out of the past is another thing altogether, a Herculean effort in that

known

and unknown landscape we might as well call the metaphysical. It's the

land

where all artists dwell, and that your years at Columbia's School of

the Arts

have prepared you to meet head on*; by now you have developed the

stamina of

Hercules, or Sisyphus, as you do the joyful, maddening, and true work

of

artists, those sometimes whistling and sometimes wretched builders and

destroyers of truth and memory, makers who take from the past-their

memories-to

create a present that shimmers with veracity and poetry. ….. Now and

then, the past and the present: didn't Boris Pasternak teach us that

there was

no separating the two, not to mention Suzan-Lori Parks in her plays,

not to

mention William Faulkner, not to mention Billie Holiday in all her

succulence

and disaster, and didn't Claude Lanzmann show in his extraordinary 1985

documentary, Shoah, how the past

weighs the present down? And hasn't Kara Walker told us how memory

works in

America, which she loves like no other place on earth because no other

place on

earth could have created Kara Walker? All of these peoples-Pasternak,

Parks,

Faulkner, Holiday, Lanzmann- they are you, the you you are about to be.

Making

something out of remembering, giving yourself that chance- there is

nothing

like it. In the preface to her haunting poem "Requiem," the great

Russian poet Anna Akhmatova wrote of the accuracy one must employ when

reporting and remembering: INSTEAD OF A

PREFACE During the

frightening years of the Yezhov terror, I spent seventeen months

waiting in

prison queues in Leningrad. One day, somehow, someone "picked me

out." On that occasion there was a woman standing behind me, her lips

blue

with cold, who, of course, had never in her life heard my name. Jolted

out of

the torpor characteristic of all of us, she said into my ear (everyone

whispered there )-"Could one ever describe this?" And I

answered-"I can." It was then that something like a smile slid across

what had previously been just a face. The artist's memory is a dangerous, necessary thing. Never disavow what you see and remember-it's your brilliant stock-in-trade: remembering, and making something out of it. Artists remember the world as it is, first, because you have to know what it is you're reinventing; that's a rule, perhaps the only one: being cognizant of your source material. I've never believed, not for one second, that art is created out of avoiding the world and its various realities. If you avoid that, you avoid life, which is your source material, you dishonor all your ghosts in the sunlight, including the person you were when I began this speech, the Columbia boys I knew and loved long ago, the politically oppressed poet who changed a face, and you, dancing with my former self before we part, and you walk proudly into your sunlit hope, ghosts and all. NYRB July 10, 2014Hilton Als July 10,

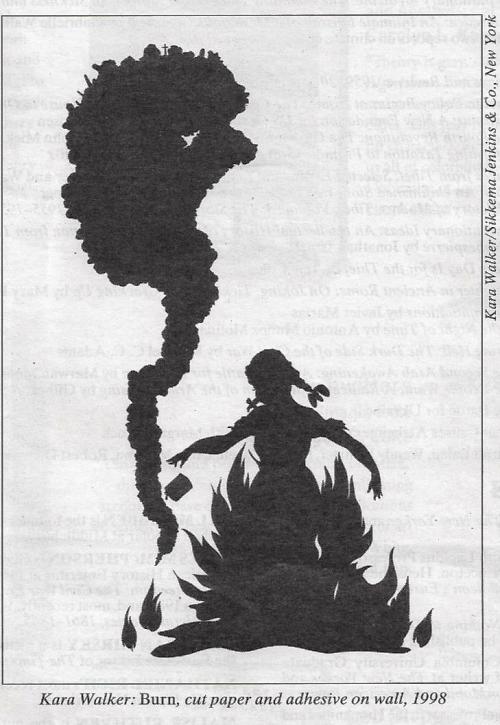

2014 Issue For Evgenia Kara

Walker/Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York Kara Walker:

Burn, cut paper and adhesive on wall, 1998 This

happened in 1967. That year, the American author Truman Capote, then

forty-three years old, published a beautiful essay he titled “Ghosts in

Sunlight.” The piece—it’s not very long—describes the author’s

experience on

the set of the film adaptation of his 1966 best-selling book, In Cold

Blood. At

one point Capote relates how the actors impersonating the real-life

protagonists in his famous “non-fiction novel” unsettled him, rattled

him, for

there they were, alive and interpreting the thoughts and feelings of

men he had

known long before, dead men he could not shake. Capote describes this

experience as being akin to watching “ghosts in sunlight”—a lovely

metaphor

about memory and the real converging to make the world something else,

and the

artist someone else, too. Standing on that film set, the Capote who had

written

In Cold Blood was a relative ghost to the film being made; he was a

specter

standing in the sunlight of his former self. I think I

understand something about the anxiety Capote expresses in the piece; I

certainly understand when he relates how, at some point during his In

Cold

Blood process, he’d fall into bed with a bottle of scotch and pass out,

the

victim of a disorienting emotional flu. Nostalgia is one thing, but

making art

out of the past is another thing altogether, a Herculean effort in that

known

and unknown landscape we might as well call the metaphysical. It’s the

land

where all artists dwell, and that your years at Columbia’s School of

the Arts

have prepared you to meet head on*; by now you have developed the

stamina of

Hercules, or Sisyphus, as you do the joyful, maddening, and true work

of

artists, those sometimes whistling and sometimes wretched builders and

destroyers of truth and memory, makers who take from the past—their

memories—to

create a present that shimmers with veracity and poetry. I wonder if

you, like me, feel, just now, like a ghost in the sunlight, awash in

memories

as your life shifts from student to professional, and your professors

become

your colleagues. I’ll pull rank now—but just for a moment—and say that

my

ghosts are probably older than yours. I mean almost Madonna old, and

her 1980s

music is there in my reminiscences along with so much more as I recall

that the

majority of my ghosts became just that during the AIDS crisis, which I

first

read about while I was a student at Columbia—in 1981 or so. I met those

now

gone boys at Columbia some time before I met you. In memory they wear

what they

wore then: Oxford button-downs, and they smoke and gossip in the sun

that

always makes the steps of Low Library—the very steps you’ve sat on

yourself—look like a sketch in a dream. Tomorrow was faraway then. And

then it

wasn’t. I see those

gone boys and hear their laughter and love them even more as I watch

you all

now in your sunlight. For your time at Columbia and your life in this

particular section of Manhattan is becoming part of your past very

quickly now,

all the moments of making your self—your artist self—mixed up these

final days

and hours before you face other realities, other dangers, other hopes,

and

other presents that are destined to become the past, too. And

undoubtedly you

will try to make art out of this beautiful ephemera, the merging of the

past

with the present, because you’re artists, chroniclers of who you are,

and who

you might be, and who we all are, together. In order to

achieve that—that is, to push further into being the kind of

truth-telling

artists I already know you are—I should tell you something about

myself, so

that we are better friends, and you can accurately transform this

moment or the

next into one of your stories. Let’s begin with my time at Columbia. I

loved

studying with great scholars ranging from Elaine Pagels to Kenneth E.

Silver—I

was an art history major in the General Studies program—but I must

confess that

I wasn’t much of a student. It didn’t

take Elaine and Ken long to suss out that I wasn’t an academic, I was a

writer.

I didn’t know how to call myself that; that is, I didn’t know what you

now

know: that there are professors out there, at the School of the Arts,

for

instance, who can help nurture your voice. So I just bungled along,

finding

much to love along the way, including authoritative reading lists that

gave me

a frame to begin understanding not just emotionally, but

philosophically and

intellectually as well, how the past leads to the present and beyond.

By

reading I discovered that art-making was a tradition that was bigger

and no

bigger than myself. I did not

feel crippled by this knowledge; in fact, I was liberated by it: being

an

artist meant you were connected to other people—ghosts—who had been as

moved by

the enterprise of creating as you are now; evidence of their love was

all the

movies and performances and books and dances and music that informed

your

present so deeply and indelibly, acts of creation that stirred your

imaginings

to the point of making you wonder: How do I make the kind of film I

want to

see, write the kind of story or poem I want to read, perform the music,

play,

or dance that is expressive of the artist I’m meant to be? In her

lovely memoir, Smile, Please, the Caribbean-born writer Jean Rhys says

that she

considered her writing to be the tiniest stream, one that trickles into

the

vast ocean that is world literature. But without those streams there

would be

no ocean, and if there is no ocean there is no shore, and if there is

no shore

there is no place for our ghosts to gather in the sunlight, those

artistic

forebears who wave us back to dry land when a project seems beyond us

and we

lose our way, which is at least half of the time. As I’ve

said, I was a terrible student. Or put in a different way: I was a

miserable

student, a dropout at heart who didn’t know how to look for, let alone

find,

what you found: a conservatory-like atmosphere that affords one the

freedom and

discipline to do one’s true life work. I didn’t come from a world

filled with

much worldly information, other than how to survive. I grew up in a

family of

West Indian women who raised their children in what social workers used

to call

“socio isolation.” First we lived in East New York, and then in Crown

Heights,

and then in Flatbush. When I stepped through those gates on Broadway,

that was

all I knew. I was a student at a time when the school was segregated by

gender,

and also you could smoke in class. This was not

the world I knew, certainly not at home. In order to acclimate myself,

I took a

great many classes at Barnard. Still, I didn’t give myself a chance to

take

advantage of the opportunities Columbia offered up because I didn’t

know how

to: it takes a long time to make it to the welcome table if you’ve been

standing at the sink of making do. Part of what

makes your experience so valuable to me is that you allowed yourself

this

experience, you are graduating with the license or degree you’ve

already

conferred on yourself—to be artists, to be thinkers, to be. As the

artist Kara

Walker noted once vis-à-vis her experience as a woman artist of color,

it just

takes a lot to give yourself permission to get into the studio, to

claim that space. If anything,

your education, the conservatory-like atmosphere the School of the Arts

has

built over the years, has helped minimize those kinds of complications,

no

matter what your race or gender, and anyway all artists feel “other.”

There’s

not an artist on God’s green earth who feels, emotionally speaking,

that he or

she has been invited to the prom. It’s in our DNA—to stand to the left

or

outside of life’s fray, in our tennis shoes, in our painter’s smocks,

in our

director’s caps, in our moth-eaten writer’s sweaters, awash in memory

even as

it becomes that in the just-now past. Your various educators understand

the

humility of creation, and something more: how to encourage and coax you

into

greater accuracy. What does your past look like, what does the present

say, and

what do your ghosts look like in the sunlight? But enough

about you. Actually, I can’t go on without you since, by now, we have

become

friends, and, like any friend, I am not ashamed to say that I am

drawing on

your confidence to admit that I loved studying art history here at

Columbia

because the field involved so many of the things that enthrall me,

still, such

as cultural production, politics, aesthetics, and words. There was an

immediate

benefit to this: it gave me a setting in which to understand the

society that

surrounded me during my time on campus in the early 1980s, a time when

New York

had, for all intents and purposes, been abandoned by the federal

government,

and the city felt strangely lawless—Andy Warhol called it a Wild West

show. It was a

place where visual artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and theater

directors like

Elizabeth LeCompte and Andrei Serban and performers such as Steve

Buscemi and

Anna Kohler and filmmakers ranging from Bette Gordon to Jim Jarmusch to

Charles

Burnett and writers like Margo Jefferson, Susan Minot, Richard Howard,

Elizabeth Hardwick—you will recognize some alumni and past and present

professors from the School of the Arts in that list, I’m no fool—were

making

work that explored New York, which felt, then, like a small exploding

Gotham

filled with extreme sunsets and light, an intense universe shaped as

much by

poverty as it was by hope and creativity. Columbia was

part of that. East Campus had yet to be built, and the whole campus, in

memory,

feels as though it were lit by a thousand cigarettes in the dark. In

fact, the

first reading I ever gave was at Columbia, at night. I was a student; a

friend

who lived downtown came up to hear me. During the reading she sat in

the front

row, eating a hoagie. Afterward, she said I should have something

behind me

while I read. A video? Some slides? I offer all

of this not by way of aimless self-revelation, but as a way of

provoking you to

remember your stories about similar incidents in your life, stories

about the

night, and who smoked what and who was doing who mixed in with outside

events,

such as the politics of your time, mixed in with the books you were

reading,

the films you were seeing, the poems you were memorizing, because all

of it is

your source material. Stories like that girl with the hoagie will end

up being

the stories you end up telling, take it from me: memory is your

greatest ally

and your primary source material, because memory is your body as it was

in the

world and the world as it was and will be; memory is the people you

have loved

or wanted to love in the world, and what are we if not bodies filled

with

reminiscences about all those ghosts in the sunlight? Now and

then, the past and the present: didn’t Boris Pasternak teach us that

there was

no separating the two, not to mention Suzan-Lori Parks in her plays,

not to

mention William Faulkner, not to mention Billie Holiday in all her

succulence

and disaster, and didn’t Claude Lanzmann show in his extraordinary 1985

documentary, Shoah, how the past weighs the present down? And hasn’t

Kara

Walker told us how memory works in America, which she loves like no

other place

on earth because no other place on earth could have created Kara Walker? All of these

people—Pasternak, Parks, Faulkner, Holiday, Lanzmann—they are you, the

you you

are about to be. Making something out of remembering, giving yourself

that

chance—there is nothing like it. In the preface to her haunting poem

“Requiem,”

the great Russian poet Anna Akhmatova wrote of the accuracy one must

employ

when reporting and remembering: INSTEAD OF A

PREFACE

During the

frightening years of the Yezhov terror, I

spent seventeen months

waiting in

prison queues in

Leningrad. One day,

somehow, someone “picked

me out.”

On that occasion there was

a woman standing behind me,

her lips

blue with cold, who, of course, had never in

her life heard my name.

Jolted out of

the torpor characteristic of all of us, she said into my ear

(everyone

whispered there)—“Could one ever describe this?” And I answered—“I

can.” It was

then that

something like a smile

slid across what had previously

been just a face. The artist’s

memory is a dangerous, necessary thing. Never disavow what you see and

remember—it’s your brilliant stock-in-trade: remembering, and making

something

out of it. Artists remember the world as it is, first, because you have

to know

what it is you’re reinventing; that’s a rule, perhaps the only one:

being

cognizant of your source material. I’ve never

believed, not for one second, that art is created out of avoiding the

world and

its various realities. If you avoid that, you avoid life, which is your

source

material, you dishonor all your ghosts in the sunlight, including the

person

you were when I began this speech, the Columbia boys I knew and loved

long ago,

the politically oppressed poet who changed a face, and you, dancing

with my

former self before we part, and you walk proudly into your sunlit hope,

ghosts

and all.

|