CHINA is smarting. A tribunal in The Hague ruled on July 12th that its claims to most of the South China Sea had no basis in international law. In the days since, China’s government has shown no sign of wanting to dig itself out of a diplomatic hole—or any sign that it thinks it is in one.

Officials had two opportunities to be emollient and passed them both up. The first came when discussing bilateral talks with the Philippines, which had brought the case. Before the verdict the Philippines’ new president, Rodrigo Duterte, had said “let’s talk.” But according to his foreign minister, Perfecto Yasay, China demanded the talks take place without reference to the tribunal’s ruling. When Mr Yasay said no, the Chinese side muttered that “we might be headed for a confrontation.” China also continued to block Philippine fishermen from their traditional grounds.

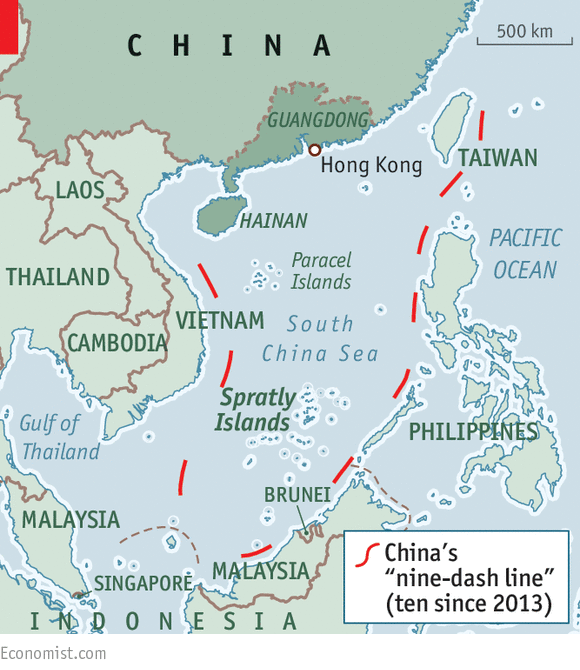

The other chance to step back came during a visit to Beijing by the chief of America’s navy, Admiral John Richardson. His opposite number, Wu Shengli, did not miss the opportunity to miss an opportunity. “We will never stop our construction on the Nansha [Spratly] islands half way, no matter what country or person applies pressure,” he said, referring to China’s controversial building of harbours and runways on disputed outcrops in the South China Sea. At least they were talking.

Bellicosity from the brass is the order of the day. According to Reuters, another Chinese admiral, Sun Jianguo, told a forum in Beijing that “freedom of navigation” by American warships in the South China Sea, designed to ensure sea lanes stay open, could “play out in a disastrous way”. A vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission, the Communist Party body that controls the armed forces, talked about beefing up combat preparedness during an inspection tour in the southern province of Guangdong. And so on.

More worrying than words were the actions. The maritime authority of Hainan, an island province off Guangdong, said it was closing an area in the South China Sea for three days while naval exercises took place. Xinhua, an official news agency, said China had recently dispatched a combat air patrol, consisting of H-6K bombers and fighters, over the South China Sea. China has been talking about setting up an Air Defence Identification Zone in the area, requiring incoming aircraft to identify themselves to its authorities. The air patrols could help China implement one. John Kerry, America’s secretary of state, has called the idea of such a zone “provocative and destabilising”.

Two things are clear. One is that stubborn nationalism is a strong feature of China’s foreign policy. The other is that Xi Jinping—China’s president, Communist Party leader and commander-in-chief—is determined to control it, just he is to dominate all aspects of China’s politics. State media have dismissed the tribunal as an American puppet, but Mr Xi does not want anti-US fervour to disrupt his diplomacy. China’s navy is still taking part in biennial naval drills called RIMPAC, hosted by America and joined by more than 20 other countries, that are under way off Hawaii. It appears to relish the prestige.

After the verdict, China’s social media started to call on people to boycott bananas from the Philippines and American brands such as iPhones and KFC, a fast-food chain. But the last thing Mr Xi wants are public demonstrations. (In the past century, patriotic protests have had a habit of turning against the government in China.) So this week, Xinhua and People’s Daily, a party newspaper, started criticising the “irrational patriotism” of social media. A picture (left) that circulated on social media of a protest outside a KFC outlet was deleted by censors. If there is one thing more important than Chinese nationalism, it seems, it is party control.

That was borne out on July 17th when the Chinese National Academy of Arts forced the closure of one of China’s most important and few remaining liberal magazines, Yanhuang Chunqiu. The decision to close it was remarkable because Mr Xi’s late father, Xi Zhongxun, was one of its most important fans. The closure was inconceivable without the younger Mr Xi’s say-so. The magazine won its spurs by challenging the party’s account of events ranging from the Communist takeover of China in 1949 to the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. But nothing may now challenge the official version—as the government’s angry defence of its “historical” claims in the South China Sea shows.