http://www.economist.com/…/21723423-communist-party-does-no…

Tờ Người Kinh Tế có

bài về vụ Đồng Tâm, GCC bị đụng tường, không

đọc được, không làm sao báo cáo, sorry.

Nhưng hãy nhớ, Hannah Arendt phán,

muốn hiểu chủ nghĩa toàn trị, chỉ cần nhớ 1 câu,

nó đếch thí cho nhân dân của nó,

dù chỉ 1 tí tự do.

Cái toàn trị của xứ Mít còn

ghê gớm hơn nữa, vì đằng sau nó, là

Cái Ác Bắc Kít, cực kỳ tàn nhẫn.

Note: Bài này đuợc 1 vị bằng hữu chôm

giùm. Tks.

Post ở đây.

Cục Ung Thư

Đồng Tâm (1)

Sẽ đi bản tiếng Mít

liền. Câu kết bài viết mới... đểu/đã/độc như

thịt vịt... làm sao:

Expect more battles to come

Âm Thanh & Cuồng Nộ:

Đây là câu chuyện của xứ Mít,

Được kể bởi Cái Ác Bắc Kít

Nó sẽ còn dài dài.

Hy vọng sẽ có nhiều cú ĐT trong

những ngày sẽ tới!

(1) Ung Thư: Từ này, chôm của TTT. TTT chôm

của Malraux, làm cái tít cho 1 bài viết,

bị đấng Trần Phong Giao, thư ký báo Văn, chôm

tiếp, làm nhan đề cho 1 tập truyện ngắn do xừ lúy biên

tập, của Thế Uyên & Duy Lam:

Nổi Chết Không Rời

[from Blog NL]

Bếp Lửa, "miêu tả không

khí Hà-nội trước 1954; đi và ở đều là

những chọn lựa miễn cưỡng, chia lìa hoặc cái chết. Lập

tức có phản ứng của những nhà văn cách mạng.

Trong một bài điểm sách trên Văn Nghệ, một nhà

phê bình hỏi tôi: "Trong khi nhân dân

miền Bắc đất nước ra công xây dựng xã hội chủ nghĩa,

nhân vật trong Bếp Lửa đi đâu?". Tôi trả lời: "Anh

ta đi đến sự huỷ diệt của lịch sử," mỗi nhà văn là một

kẻ sống sót.

Tác phẩm thứ nhì của tôi, Ung Thư

(1970) có thể coi như tiếp nối Bếp Lửa. Ung Thư là chấp

nhận giữa "vô thường", và chút hơi ấm của nỗi chết

(l'existence de notre acceptation entre la vanité et la tièdeur

de mort). Cuốn sách chẳng bao giờ được in ra...

TTT trả lời Le Huu Khoa, trong Thơ giữa chiến tranh

và Trại Tù

“Thơ Thanh Tâm Tuyền

phải được đặt trong vị trí 'di cư' và 'chiến tranh'

của một thành phố mở ra thế giới bên ngoài là

Sài Gòn. Không có hoàn cảnh hay

khung cảnh ấy, người ta khó cảm hay yêu thơ của ông.”

Quỳnh Giao.

Hai cái tít

Ung Thư, và Nỗi Chết Không Rời, như trên cho thấy,

là từ câu của Malraux, GCC nhớ đại khái, hình

như trong La Voie

Royale, mais accepter vivant la vanité de son existence,

comme un cancer, vivre avec cette tièdeur de mort dans la main.

Nhưng hãy chấp nhận cái "vanité"

[tạm dịch, theo cái nội dung, context, ỏ đây, cái

vô thường] của hiện hữu, như cục ung thư, sống với nỗi ấm áp

của cái chết ở trong lòng bàn tay

V/v Vưỡn chuyện Cái Ác Bắc Kít:

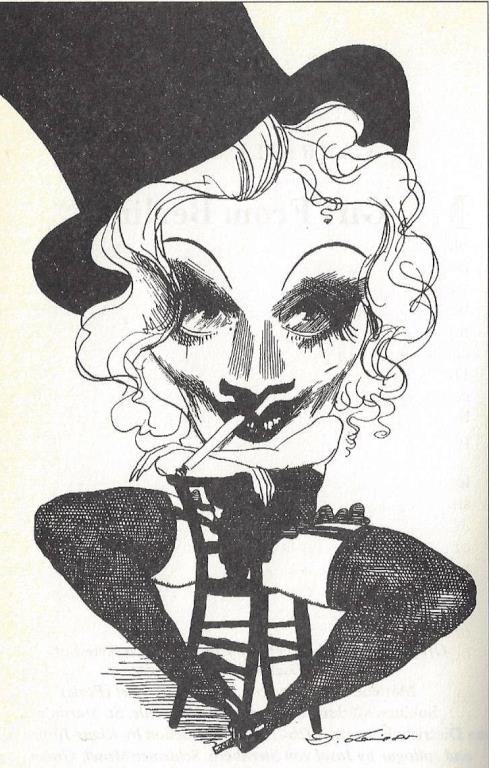

Marlene Dietrich by David

Levine

GABRIELE ANNAN

Girl From Berlin

Originally published February

14,1985, as a review of Marlene Dietrich's ABC, Ungar Marlene D.

by Marlene Dietrich. Grasset (Paris) Sublime Marlene by Thierry de

Navacelle. St. Martin's

Marlene Dietrich: Portraits

1926-1960, introduction by Klaus-Jurgen Sembach, and epilogue by

losefvon Sternberg. Schirmer/Mosel; Grove Marlene a film directed

by Maximilian Schell, produced by Karel Dirka. Dietrich by Alexander

Walker. Harper and Row

Among the rarities Schell

has to show is a scene from Orson Welles's Touch of Evil (1958), in which

Dietrich was only a guest star. She plays the madame of a Texas brothel,

Welles a corrupt, alcoholic police chief on the skids. He comes into the

brothel and finds her alone at a table in the hall.

"You've been reading the cards, haven't you?" [he says].

"I've been doing the accounts."

"Come on, read the future for me."

"You haven't got any."

"Hm ... what do you mean?"

"Your future's all used up. Why don't you go home?"

Dietrich's voice is deadpan, but it breaks your heart

all right with a Baudelairean sense of the pathos of human depravity,

degradation, and doom.

“Cô gái từ Berlin”

là 1 bài viết về nữ tài tử điện ảnh người Đức,

Marlene Dietrich.

Trong phim “Cánh Đồng

Bất Tận", em đóng vai 1 bướm Xề Gòn, buồn buồn ngồi

bói Kiều. Một tên cớm Bắc Kít bước vô, ra

lệnh:

-Coi cho ta 1 quẻ về tương lai.

Ngài đâu còn?

-Mi nói sao?

Tương lai của Ngài xài hết rồi, sao Ngài

không về lại xứ Bắc Kít của Ngài đi?

Giọng em bướm trong Cánh Đồng Bất Tận mới dửng

dưng, bất cần đời làm sao, nhưng bất cứ 1 tên Mít nào

nghe thì cũng đau thốn dế, khi nghĩ đến 1 xứ Mít tàn

tạ sau khi Bắc Kít chiếm trọn cả nước.

Đúng là THNM!

No man’s land

Property disputes are Vietnam’s biggest political

problem

The Communist party does not know how to handle

them

Miền đất không người

[Thuật ngữ này, cũng

cực đểu, với tờ báo cực đểu - dưới con mắt của Vẹm, tờ

báo đã từng ví đại hội Đảng như là

của 1 loài bò sát, nhớ đại khái (1)

– và thường dùng trong văn học, để chỉ một miền

đất còn trinh nguyên, chờ con người khai phá]

Những cuộc tranh luận về tài sản là

vấn đề chính trị lớn lao nhất của Việt Nam

Đảng CS không biết làm sao “xử lý”

chúng.

Trong nhiều năm những cư dân Đồng Tâm,

một làng ở bìa của thủ đô Việt Nam, đã

chiến đấu cho cái quyền được tiếp tục chăm nom những mảnh

vườn, thửa đất của họ, trên 1 vùng đất được khoanh

vùng là thuộc quyền sở hữu của quân đội, cho

mục đích phát triển của họ. Sự nhẫn nại của họ “bốc

hơi” vào Tháng Tư khi nhà cầm quyền bắt giữ một

nhóm người già cả mà được dân làng

tin cậy, và chọn họ là những người đại diện cho họ để

“thúc đẩy, nài ép” trường hợp của họ với nhà

cầm quyền. Dân làng bèn áp đảo chừng trên

chục cớm VC được phái tới để bảo đảm công cuộc định

cư, và giam giữ họ ở nhà hội của làng (như trong

hình). Những người ủng hộ dựng chướng ngại vận, ngăn chặn mọi con

đường tới nhà hội, và đe doạ sẽ nổi lửa, thiêu sống

Cớm VC!

Hà, hà!

(1)

http://www.tanvien.net/thoi_su/Trong_Lu_by_Nguoi_Kinh_Te.html

Carry on, Nguyen Phu Trong

Cứ thế tiếp tục, Trọng Lú!

Chính trị xứ Mít VC

Politics in Vietnam

Reptilian manoeuvres

Trò ma nớp của loài bò sát

A colourful prime minister goes, as the grey men

stay

Một tên thủ tướng màu mè ra

đi, một lũ muối tiêu ở lại

Cuộc vây hãm kéo dài cả tuần lễ tiếp

theo, đánh dấu cú leo thang mới, trong những trận đánh

vô phương kết thúc - endless battles - ở Việt Nam, về đất

đai - duyên do đầu tiên của những khiếu nại- dùng danh

từ lịch sự thì là "nguyện vọng" của nhân dân

- ở xứ Mít, và là 1 trong những cơn nhức đầu to đầu

nhất, của Đảng CS. Người dân Mít theo dõi "bi kịch

của chúng ta", trên từng cây số trên mạng xã

hội, và sau cùng thì mới ghé mắt nhòm

báo chí nhà nước.

Bi kịch vươn tới bưóc ngoặt sững sờ nhất, với màn

ông Trùm Thủ Đô, để giải thoát con tin, đã

hứa lèo, sẽ không truy cứu hình sự dân làng,

và sẽ tái cứu xét nguyện vọng của họ.

Note: BBC đi bài này, ở đây:

http://www.bbc.com/vietnamese/vietnam-40285093

No man’s land

Property disputes are Vietnam’s biggest

political problem

The

Communist party does not know how to handle them

FOR years residents of Dong Tam, a village on the edge of Vietnam’s capital,

have fought for the right to continue tending farms on land earmarked for

military development. Their patience evaporated in April, when authorities

arrested a group of elders whom they had chosen to press their case with

the government. The villagers overpowered dozens of policemen who had been

sent to secure the settlement, holding them captive in a municipal hall (pictured

above). Supporters blocked nearby lanes with rubble, and at least one hothead

threatened to set the hall on fire.

The week-long siege that followed marked a new escalation in Vietnam’s

endless battles over land—the primary cause of complaints in the country

and one of the ruling Communist Party’s biggest headaches. Vietnamese followed

the drama on social media and, eventually, in the state press. But just as

startling was the government’s capitulation, negotiated in person by Hanoi’s

mayor. Authorities secured the hostages’ release by promising not to prosecute

the villagers, and by pledging to re-examine their complaint.

Vietnam’s zippy economy, growing at more than 6% annually, demands ever

more room for roads, bridges, dams and industrial parks. Each year swelling

cities must find space for a million new arrivals. The total area of farmland

lost to development over the past two decades is difficult to quantify. One

certainty is that it far exceeds the acreage that changed hands during violent

upheavals in the 1950s, when the Communist rulers of North Vietnam forcibly

redistributed farmland.

Transformation on this scale would provoke ire anywhere, but it is especially

problematic in Vietnam, a one-party state where the government grants usage-rights

but insists all land belongs to the state. Compensation for forcible acquisitions

is far below market rates. Consultations can be superficial, and courts

rarely entertain appeals. Evicted residents sometimes complain of collusion

between local officials and developers. Spotty registries make it hard to

adjudicate competing claims, as seems to be the case in Dong Tam.

These foibles distort Vietnam’s development. For one thing, the cheap price

of land on the fringes of cities has encouraged sprawl. Last year the World

Bank warned that by building outwards rather than upwards urban authorities

are raising the cost of providing public services, and negating efforts

to build zesty business clusters. But far more worrying for the party is

the visceral anger that forced relocations and weak land rights can unleash.

Official figures suggest that land disputes of one sort or another lie behind

more than two-thirds of all the complaints made to bureaucrats. Unhappiness

among country-dwellers undermines support for the Communist Party in its

core constituency.

Too often authorities have resorted to roughing up hold-outs in land disputes,

even when resistance is peaceful. In September a court in the capital handed

a 20-month jail sentence to Can Thi Theu, a well-known land-rights campaigner

who has been banged up once before. But lately the party has also been re-examining

its rules. A new land law passed in 2013 failed to recognize private ownership

but did extend by 50 years a slew of leases that were about to expire. It

re-centralized some decision-making over land use (in part to restrain corrupt

provincial officials) and required party bigwigs to use stricter tests when

evaluating projects that would require mass displacements. It also gave

officials more discretion over compensation, to allow more generous settlements.

The results are mixed. An annual survey published by the UN finds that

the total number of land seizures has fallen over the past three years.

But a third of those affected still report receiving no compensation, and

another quarter think their pay-outs unfair. Cadres in Hanoi have been slow

to issue the guidelines needed to make the new rules effective. John Gillespie

of Monash University says that so far the reforms have added up to “very

little”.

Petitioners are at least finding it ever easier to draw the public’s attention

to their problems. Although journalists in Vietnam remain shackled by censorship,

the party has neither the will nor the wealth to sanitize social media.

Facebook has become an outlet for popular anger about all sorts of unfairness

(posts on the platform are still helping to sustain outrage over a toxic

spill that poisoned miles of coastline last year). Had the dispute in Dong

Tam happened ten years ago “no one would have heard about it”, says a local.

The government’s surrender was probably inevitable given online attention.

Two months on, the government is still trying to close the case without

setting precedents it may regret. Inspectors have yet to release their report

into the villagers’ claims, which they had promised within 45 days. Campaigners

lambasted what looked like a U-turn on June 13th, when police announced

that they would, after all, mount cases against some of Dong Tam’s residents.

The party has presumably decided that doing nothing risked encouraging other

aggrieved citizens to resort to attention-grabbing violence.

One theory in the capital is that the courts will pass relatively lenient

sentences, and that some kind of quiet compromise will be found to save

face. But even if the government finds a fudge for the dispute in Dong Tam,

lots more farmland will be paved over before Vietnam’s galloping urbanisation

runs its course. Expect more battles to come.