|

PRAISE FOR AFTER NATURE

"Before the four incomparable novels that made him a world figure in literature, W G. Sebald wrote the free verse triptych After Nature, now fluently translated by Michael Hamburger. Aftter Nature sets the pattern of the novels: reveries on distant lives alongside something like autobiography. This and the later books sustain a search for threads along which conscious and lost memories in private life connect with surviving and lost evidence about lives and worlds long gone .... As in Sebald's novels, images and echoes link narrative meditations in this work." -The San Francisco Chronicle " [There are] three poems in After Nature. The first is about the sixteenth- century painter Matthias Grunewald, the second about the nineteenth- century botanist Georg Steller, [and the third] is an autobiographical prose poem. The scientist, the artist, and the writer all trying to make sense of life and death, pulled between images of white snow in the Alps and green forests and pastures. The late W G. Sebald is a writer who often stops, in his quest for meaning, with the unexplained coincidence. [Sebald] will not translate coincidence for his readers, and this is the secret of his perfect timing. Here is the other secret: We are willing to be carried along in a haze of not quite understanding because Sebald also revels in the pure music of words .... Only by suspending readerly willfulness will you be able to float weightless through his writing." -Los Angeles Times " Remarkably lucid English translation ... After Nature consists of three interrelated narratives, spanning different historical periods .... It is Sebald's graphic description of a subject in a Grunewald painting that seems to capture the random, irrational movements of nature most vividly." - The Washington Post "Europe ... is a continent soaked in bloody history; its every street corner, its every green and lovely field has likely borne witness to some episode of war or religious terror or plague. W G. Sebald ... was a master at evoking this haunted Europe .... By the time he died on a rural English road, he had been acknowledged as one of the great postwar European writers .... Now, After Nature, a book of three long poems by Sebald, is being published in English for the first time .... This translation (by his friend Michael Hamburger) reveals him to be a poet of subtlety and lingering power." -Time Out New York "His work recalls Gustav Herling's Journal Written at Nipht: or, when he includes uncaptioned photographs, the early work of Sebald's contemporary, Michael Ondaatje. Comparisons, however, do no justice to Sebald. Eventually, even the most familiar prose unit, the paragraph, dissolves in his hands. He was an original." -The Philadelphia Inquirer "The three long poems in After Nature ... anatomize the correspondence between the life and the work, the work and the world, the world and the life. Wary of abstraction, alert to history's detours and infernal turns, Sebald had the ability to consort with the unspeakable .... After Nature is Sebald's alpha and omega, at once the first and last of his literary works, and a seedbed for his later projects .... Sebald, near the end of After Nature, under a lowering sky, writes, 'What's dead is gone/forever,' then a shard from Lear: 'What did'st /thou say?' More questions follow, and the section dissolves into 'Water? Fire? Good? /Evil? Life? Death?' it's the one moment in his entire body of work where he gives the impression of losing control, and the effect is liberating and haunting." -The Village Voice "The art that he created is of near-miraculous beauty." -The New Republic "After Nature, which now appears in an excellent translation by Michael Hamburger, is a work of considerable scope and ambition .... The aims of the Grunewald and Steller poems are not biographical or historical in any ordinary sense. Though the scholarship behind them is thorough ... scholarship takes second place to what he intuits about his subjects and perhaps projects upon them .... It is thus best to think of Grunewald and Steller as personae, masks that enable Sebald to project back into the past a character type, ill at ease in the world, indeed in exile from it, that may be his own but that he feels possesses a certain genealogy which his reading and researches can uncover .... 'Dark Night Sallies Forth,' the third of the poems in After Nature, is more overtly autobiographical. Here, Sebald, as 'I,' takes stock of himself as a person but also as inheritor of Germany's recent history." -The New York Review of Books W.G. Sebald, Bombing and Thomas Bernhard

The first thing to be said

about W G. Sebalds books is that they always had a posthumous

quality to them. He wrote - as was often remarked - like a ghost. He

was one of the most innovative writers of the late twentieth century;

and yet part of this originality derived from the way his prose felt

as if it had been exhumed from the nineteenth.Geoff Dyer Điều đầu tiên được nói về những cuốn sách của Sebald, là chúng đều có cái air di cảo. Ông ta viết, như một hồn ma. Là 1 trong những nhà văn làm mới số 1 của hậu thế kỷ 20, tuy nhiên, 1 phần của cái uyên nguyên, là từ cái cách ông viết văn xuôi, như thể chúng được lôi lên từ cái xác thế kỷ 19! Gấu biết đến Sebald là qua 1 bài viết của Sontag. Bà coi ông, 1 thứ nhà văn của nhà văn. Viet Thanh Nguyen coi ông là “hero” của mình, và rất mê lối viết trộn lẫn nhiều thể loại, phê bình, văn xuôi, hồi tưởng…. Gấu đọc Sebald khác hẳn, một kẻ săn hồn ma, như chính ông tự nhận, hay, với GCC, một lương tâm của nước Đức hậu chiến. Vả chăng tuy trộn lẫn nhiều thể loại, trong khi viết giả tưởng, nhưng với những bài viết đúng là phê bình, hay biên khảo, Sebald xuất hiện như 1 vị quan tòa, và văn của ông, là thứ phán đoán, truy xét, hỏi tội, Judgment. TV giới thiệu bài viết mới có được, về ông, nhân mới xuống phố. Trong bài viết, trong cuốn trên, tác giả nối kết Sebald, với vụ không kích, và với Thomas Bernhard. Bài viết của Dyer về Sebald xoáy vào cuốn mà Gấu mê nhất của ông, Về lịch sử tự nhiên về huỷ diệt, “On the natural history of destruction”. TV “phải” mua cuốn sách, để “phải” đi 1 đường về Sebald, là vì bài viết này, chưa kể bài viết về “Cuộc Tình Bỏ Đi” của Scott Fitzgerald, “Tender Is the Night” [cuốn “Một Chủ Nhật Khác” là cùng dòng với nó] Cách đọc W.S. Sebald của cái tay được Pulitzer, mà anh ta gọi là “hero” của anh ta, thật là tếu, nhưng thôi bỏ, viết về Sebal thú hơn nhiều, nhân vớ được After Nature. Toàn bài viết của Coetzee, trên tờ NYRB, GCC có, nhưng do Cô Út, gặp khó khăn về kinh tế, tiền bạc, tính bán nhà, mua cái nhỏ hơn, không có chỗ chứa sách nữa, nên cho vô thùng cả 1 kho sách báo, tính vứt thùng rác tất cả. Bố già rồi, sắp chết rồi, ai đọc, cho thư viện họ cũng không lấy… Ui chao, cứ mỗi lần dọn nhà, là bỏ 1 số, lần này, chắc là bỏ hết. Thê "nương" quá! https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/apr/27/wg-sebald-place-country-review Sách & Báo Quoc Tru Nguyen shared a memory.April 5, 2012

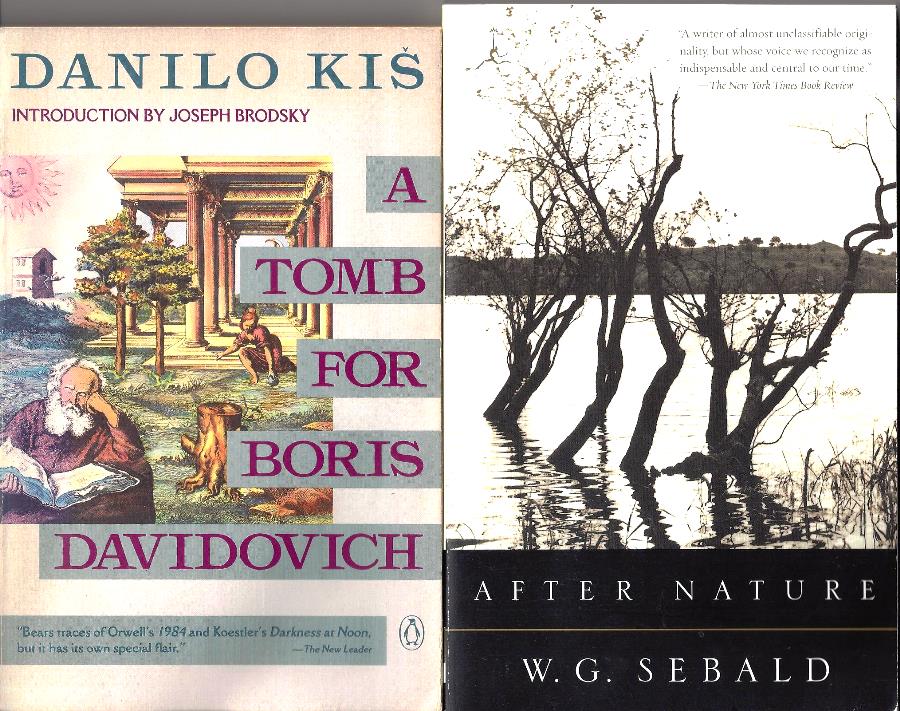

Second-hand! Quà SN tuyệt vời! Bảnh hơn "Bóng Đen & 1984", Joseph Brodsky, trong bài Intro khen nức nở. Quả đúng như thế. Cả hai ông kia, thực sự không phải là nhà văn! Tin Văn sẽ đi liền bài Intro. Tập thơ Sebald thì khỏi nói rồi. Xin giới thiệu bài của Coetzee dưới đây: Kẻ thừa kế của 1 Lịch sử U tối

… Weiss to attend the Auschwitz

trial in Frankfurt. He may also have been motivated before the event

by the hope, never quite extinguished, "that every injury has its equivalent somewhere and can be truly

compensated for, even if it be through the pain of whoever inflicted

the injury." This idea, which Nietzsche thought was the basis of our sense

of justice and which, he said, "rests on a contractual relationship between

creditor and debtor as old as the concept of law itself”…

Heir

of a Dark HistoryW.G. Sebald: The Remorse of the Heart. On Memory and Cruelty in the Work of Peter Weiss Weiss tham dự tòa

án xử vụ Lò Thiêu ở Frankfurt. Có thể là do ông vẫn còn hy vọng, một niềm

hy vọng chẳng hề tàn lụi, rằng, “mọi tổn thương thì có cái phần

tương đương của nó, ở đâu đó, và có thể thực sự được đền bù, bù trừ,

bồi hoàn, ngay cả, sự bồi hoàn này thông qua nỗi đau của bất cứ kẻ nào gây

ra sự tổn thương”. Tư tưởng này Nietzsche nghĩ, nó là cơ sở của cảm quan

của chúng ta về công lý, và nó, như ông nói, “nằm trong liên hệ có tính

khế ước, giữa chủ nợ và con nợ, và nó cũng cổ xưa, lâu đời như là quan niệm

về luật pháp, chính nó” Moi, je traine le fardeau de la

faute collective, dis-je, pas eux. Gấu cũng có thể nói như

thế: J.M. Coetzee October 24, 2002 Issue After Nature by W.G. Sebald, translated from the German by Michael Hamburger Random House, 116 pp., $21.95 http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2002/10/24/heir-of-a-dark-history/

From INTELLIGENT LIFE Magazine,

Spring 2011 The essential theme of W.G. Sebald’s

books is memory: how painful it is to live with, how dangerous it can be

to live without it, for both nations and individuals. The narrators

of his books—of which “Austerlitz” and the four linked narratives of exile

in “The Emigrants” are the most compelling—live in a state of constant reminder.

Everything blends into everything else: places, people, their stories and

experiences, and above all different times, which seep into each other and

blur together, often in long, unmoored passages of reported speech. The narrator

of “Vertigo” gives a concise account of this method: “drawing connections

between events that lay far apart but which seemed to me to be of the same

order”. Key decision: To invent his own hybrid form.

Sebald’s main works blend travelogue and meditation, fiction with history

and myth. They have a narrator who both is and is not Sebald himself: a spectral

character who is sensitive, digressive and restless, compulsively peregrinating

around Europe and its past. Strong points: Finding a voice to fit his preoccupations.

His sentences are looping, reflexive, moving forward yet endlessly turning

back on themselves. By the time he wrote “Austerlitz”, the last book he published

before his death, Sebald had more or less dispensed with paragraph breaks

altogether. This fluidity creates a feeling, as the character Austerlitz

says of his own sense of history, that “time will not pass away, has not

passed away, that I can turn back after it”—clauses that are themselves part

of a much longer, circular sentence. This is a style that tries to unbury

the dead through syntax. Golden rule: Obliqueness, or, as one critic

put it, tact. Sebald’s prose is finely wrought yet unflashy. His punctuation

is rarely more exotic than the comma; his vocabulary is unadorned. Similes

are uncommon: he deals instead in a sort of luminous reality. As in style,

so in content. Asked about his approach to the horrors of 20th-century history—his

work circles the Nazi Holocaust as if it were a mountain—Sebald once said

that his aim was to intimate “to the reader that these subjects are constant

company; their presence shades every inflection of every sentence one writes”,

without describing the camps and catastrophes directly. It is loss, rather

than bloodshed, that his books lament. Favourite trick: Putting pictures into the text

that subtly reinforce these themes. They are black-and-white, uncaptioned

and unexplained—pictures of people, but also train tickets, restaurant receipts,

maps and other relics. They seem to advertise the veracity of the stories

they appear in, yet they are artful and calculated. The images are often

poignant, at once bringing back forgotten people and confirming that they

are irrevocably lost. They point up a question that is at the heart of Sebald’s

work: why do we cling on to some things from the past while the rest of it

escapes us? Role models: In the way it samples and fractures different subjects and stories, Sebald’s work is almost post-modern. Jorge Luis Borges is cited by some as a key influence on him. And yet his sentences are also plangently old-fashioned, sometimes reminiscent, for readers in English, of medieval periods. There are echoes of Thomas Malory and Thomas Browne and, in his dextrous weaving of complementary tales, of Ovid. Typical sentence: Many of the finest are too long to cite, so this, from “The Emigrants”, will have to do: “And so they are ever returning to us, the dead.” Vintage Classics reissue three of Sebald’s books this year: "The Emigrants",March; "Rings of Saturn", April; "Vertigo", June |