|

BOOK 2:

ANIMAL FARM

BY GEORGE ORWELL

April

30, 2007

To

Stephen Harper,

Prime Minister of Canada,

From a Canadian writer,

With best wishes,

Yann Martel

P.S. Happy birthday

Dear

Mr. Harper,

Now

that your Flames have

been knocked out of the playoffs I guess you'll have more free time on

your

hands.

I fear that some may

criticize me for the second book I am sending you, Animal Farm, by

George

Orwell. It's so well known, and it's another book by a dead white male.

But

there is time yet to be representative of all those who have harnessed

the word

to express themselves-believe me, they are varied and legion-unless you

lose

the next election, which would likely give you even more time to read,

but not,

alas, according to my suggestions.

Many of us read Animal Farm

when we were young perhaps you did too-and we loved it because of the

animals

and the wit. But it's in our more mature years that its import can

better be

understood.

Animal Farm has some commonalities

with The Death of Ivan Ilych: both are short, both show the

reality-changing

power of great literature, and both deal with folly and illusion. But

whereas

Ivan Ilych deals with individual folly, the failure of one individual

to lead

an authentic life, Animal Farm is about collective folly. It is a

political

book, which won't be lost on someone in your line of business. It deals

with

one of the few matters on which we can all agree: the evil of tyranny.

Of

course a book cannot be reduced to its theme. It's in the reading that

a book

is great, not in what it seeks to discuss.

But I also have a personal

reason for why I've chosen Animal Farm: I aspire to write a similar

kind of

book.

Animal Farm first. You will

notice right away the novel's limpid and unaffected style, Orwell's

hallmark.

You get the impression the words just fell onto the page, as if it were

the

easiest, the most natural thing in the world to write such sentences

and paragraphs

and pages. It's not. To think clearly and to express oneself clearly

are both

hard work. But I'm sure you know that from working on speeches and

papers.

The story is simple. The

animals of Manor Farm have had enough of Farmer Jones and his

exploitative ways

so they rebel, throw him out, and set up a commune run according to the

highest

and most egalitarian principles. But there's a rotten pig named

Napoleon and

another one named Squealer-a good talker he-and they are the nightmare

that

will wreck the dream of Animal Farm, as the farm is renamed, despite

the best

efforts of brave Snowball, another pig, and the meek goodness of most

of the

farm animals.

I've always found the end of

Chapter II very moving. There's the question of five pails of milk from

the

cows. What to do with them, now that Farmer Jones is gone and the milk

won't be

sold? Mix it with the mash they all eat, hints a chicken. "Never mind

the

milk, comrades!" cries Napoleon. "The harvest is more important.

Comrade Snowball will lead the way. I shall follow in a few minutes."

And

so off the animals go, to bring in the harvest. And the milk? Well, "

...

in the evening it was noticed that the milk had disappeared."

With those five pails of

white milk the ideal of Animal Farm, still so young, begins to die,

because of

Napoleon's corrupted heart. Things only get worse, as you will see.

Animal Farm is a perfect

exemplar of one of the things that literature can be: portable history.

A

reader who knows nothing about twentieth-century history? who has never

heard

of Joseph Stalin or Leon Trotsky or the October Revolution? Not a

problem:

Animal Farm will convey to that reader the essence of what happened to

our neighbors

across the Arctic. The perversion of

an ideal,

the corruption of power, the abuse of language, the wrecking of a

nation - it's

all there, in a scant 120 pages. And having read those pages, the

reader is

made wise to the ways of the politically wicked. That too is what

literature

can be: an inoculation.

And now the personal reason

why I've sent you Animal Farm: the Jewish people of Europe

murdered at the hands of the Nazis also need to have their history made

portable.

And that is what I'm trying to do with my next book. But to take the

rubble of

history-so many tears, so much bloodshed-and distil it into some few

elegant

pages, to turn horror into something light-it's no easy feat.

I offer you, then, a literary

ideal of mine, besides a great read.

Yours truly,

Yann Martel

P.S. Happy birthday.

*

Trại Loài Vật là thí dụ tuyệt

hảo về những điều mà văn chương có thể đem đến cho chúng ta: một thứ

lịch sử cầm

tay. Một độc giả chẳng biết tí gì về thế kỷ thứ 20, Stalin là thằng chó

nào, Trốt

Kít quái vật hả, Cách Mạng Tháng 10 quái thai ư: Trại Loài Vật sẽ chuyên chở tới

cho vị độc giả đó cái cốt yếu, cốt tủy về điều gì đã xẩy tới cho những

người láng

giềng ở bên kia Bắc Cực của chúng ta [dân Canada]: Cái quái thai, tởm

lợm,

bại hoại của một lý tưởng [giải phóng, thống nhất đất nước, thí dụ], sự

hư ruỗng, thối nát

của quyền lực, sự lạm dụng ngôn từ, sự băng hoại của cả một quốc gia –

tất cả đều

có ở trong đó, chỉ trong một tiếng nấc của trên trăm trang sách. Và khi

đọc những

trang này, độc giả trở nên minh mẫn hơn, nhờ uống 'lầm' thuốc độc chính

trị! Điều

này thì cũng là văn chương: Sự tiêm chủng vắc xin!

Ui

chao, đúng là trường hợp đã

xẩy ra cho GNV: Giả sử những ngày mới lớn không vớ được Đêm giữa Ngọ,

thì thể nào

cũng nhẩy toán, lên rừng làm VC, phò Hoàng Phủ Ngọc Tường, đúng như một

tên đệ

tử của Thầy Cuốc 'chúc' Gấu!

Đoạn trên

thật là tuyệt cú mèo, nhưng thua… Brodsky khi

ông viết về thơ, về Kinh Cầu: "Ở vào một vài giai đoạn của lịch sử, chỉ

có

thơ mới có thể chơi ngang ngửa với thực tại, bằng cách nhét chặt nó vào

một cái

gì mà nhân loại có thể nâng niu, hoặc giấu diếm, ở trong lòng bàn tay,

một khi

cái đầu chịu thua không thể nắm bắt được. Theo nghĩa đó, cả thế giới

nâng niu

bút hiệu Anna Akhmatova."

Và bây giờ cái lý

do rất cá nhân tại sao tôi viết ‘mấy lời’ gửi ông, kèm cuốn Trại Loài

Vật: người

Do Thái Âu Châu, bị Nazi sát hại cũng cần có lịch sử của họ, dạng cầm

tay. Và đó

là điều tôi cố gắng làm với cuốn sách tới của tôi.

Nhưng căng lắm đấy,

tôi tự nhủ tôi, làm sao sàng lọc từ đống rác lịch sử, [lịch sử Mít cùng

cuộc

chiến đỉnh cao của nó] với bao nhiêu là máu, là lệ, vào một tiếng nấc,

của vài

trang [Tin Văn], làm sao biến sự ghê rợn, điều tởm lợm, kinh hoàng

thành một điều

gì nhẹ nhàng ư ảo, [trên không gian net], chẳng ngon cơm một tí nào

đâu!

BOOK 49:

THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA

BY ERNEST HEMINGWAY

February 16, 2009

To Stephen Harper,

Prime Minister of Canada,

From a Canadian writer,

With best wishes,

Yann Martel

Dear Mr. Harper,

The famous Ernest

Hemingway. The Old Man and the Sea is one of those works of

literature that most everyone has heard of, even those who haven't read

it. Despite its brevity 127 pages in the well-spaced edition I am

sending you it's had a lasting effect on English literature, as has

Hemingway's work in general. I'd say that his short stories, gathered

in the collections In Our Time, Men

without Women and Winner Take

Nothing, among others, are his greatest achievement and above

all, the story "Big Two-Hearted River" but his novels The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms and

For Whom the Bell Tolls are more widely read.

The

greatness of Hemingway lies not so much in what

he said as how he said it. He took the English language and wrote it in

a way that no one had written it before. If you compare Hemingway, who

was born in 1899, and Henry James, who died in 1916, that overlap of

seventeen years seems astonishing, so contrasting are their styles.

With James, truth, verisimilitude, realism, whatever you want to call

it, is achieved by a baroque abundance of language. Hemingway's style

is the exact opposite. He stripped the language of ornamentation,

prescribing adjectives and adverbs to his prose the way a careful

doctor would prescribe pills to a hypochondriac. The result was prose

of revolutionary terseness, with a cadence, vigor and elemental

simplicity that bring to mind a much older text: the Bible.

That combination is not fortuitous. Hemingway was

well versed in biblical language and imagery and The Old Man and the Sea can be

read as a Christian allegory, though I wouldn't call it a religious

work, certainly not in the way the book I sent you two weeks ago, Gilead, is. Rather, Hemingway uses Christ's passage

on Earth in a secular way to explore the meaning of human suffering.

"Grace under pressure" was the formulation Hemingway offered when he

was asked what he meant by "guts" in describing the grit shown by many

of his characters. Another way of putting that would be the

achieving of victory through defeat, which matches more deeply, I

think, the Christ-like odyssey of Santiago, the old man of the title.

For concerning Christ, that was the Apostle Paul's momentous insight

(some would call it God's gift): the possibility of triumph, of

salvation, in the very midst of ruination. It's a message, a belief

that transforms the human experience entirely. Career failures, family

disasters, accidents, disease, old age-these human experiences that

might otherwise be tragically final instead become threshold events.

As I was thinking about Santiago and his epic

encounter with the great marlin, I wondered whether there was any

political dimension to his story. I came to the conclusion that there

isn't. In politics, victory comes through victory and defeat only

brings defeat. The message of Hemingway's poor Cuban fisherman is

purely personal, addressing the individual in each one of us and not

the roles we might take on. Despite its vast exterior setting, The Old

Man and the Sea is an intimate work of the soul. And so I wish upon you

what I wish upon all of us: that our return from the high seas be as

dignified as Santiago's.

Yours

truly, Yann Martel

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

(I899-1961) was an American journalist, novelist and short story

writer. He is internationally acclaimed for his works The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms,

For Whom the Bell Toll and his Pulitzer Prize-winning novella, The Old Man and the Sea.

Hemingway's writing style is characteristically straightforward and

understated, featuring tightly constructed prose. He drove an ambulance

in World War I, and was a key figure in the circle of

expatriate-artists and writers in Paris in the 1920s known as the "Lost

Generation.” Hemingway won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954.

Tây đặc một thời.

BONJOUR

TRISTESSE BY

FRANCOISE SAGAN

June 25,2007

To Stephen Harper,

Prime Minister of Canada,

From a Canadian writer,

With best wishes,

Yann Martel

Dear Mr. Harper,

From London, England, I'm sending you an English translation of a

French novel. In this novel people smoke, people get slapped in the

face, people drink heavily and then drive home, people have nothing but

the blackest coffee for breakfast, and always people are concerned with

love. Very French d’une certaine epoque.

Bonjour

Tristesse

came out in France in 1954. Its author, Francoise Sagan, was nineteen

years old. Immediately she became a celebrity and her book a bestseller.

More than that: they both became symbols.

Bonjour

Tristesse

is narrated in the first person by seventeen year-old Cecile. She

describes her father, Raymond, as "a frivolous man, clever at business,

always curious, quickly bored, and attractive to women." The business

cleverness is never mentioned again, but clearly it has allowed Raymond

to enjoy freely his other attributes, his frivolity, curiosity, boredom

and attraction, all of which revolve around dalliances of the heart and

loins. He and his beloved daughter share the same temperament and they

are in the south of France for the summer holidays with Elsa, his

latest young mistress. This triangle suites Cecile perfectly and she is

assiduous at pursuing her idle seaside pleasures, which come to include

Cyril, a handsome young man who is keen on her.

But all is ruined when her father invites Anne to stay with them. She's

an old friend of the family, a handsome woman her father's age, made of

sterner, more sober stuff. She starts to meddle in Cecile's life.

Worse, a few weeks after arriving, fun Elsa is dumped when Raymond

starts a relationship with Anne. And finally, not long after, Anne

announces that she and her father are planning to get married. Cecile

is aghast. Her serial frolicker of a father and Anne, husband and wife?

She, Cecile, a stepdaughter to Anne, who will work hard to transform

her into a serious and studious young person? Quel cauchemar!

Cecile sets to work to thwart things, using Elsa and Cyril as her

pawns. The results are tragic.

After the grim work of the Second World War and the hard work of the

post-war reconstruction, Bonjour Tristesse burst onto the

French literary scene like a carnival. It announced what seemed like a

new species, youth, la jeunesse, who had but one message: have

fun with us or be gone; stay up all night at a jazz club or never come

out with us again; don't talk to us about marriage and other boring

conventions; let's smoke and be idle instead; forget the future who's

the new lover? As for the tristesse of the title, it was an

excuse for a really good pout.

Such a brash, proudly indolent attitude, coming with an open contempt

for conventional values, landed like a bomb among the bourgeoisie.

Francoise Sagan earned herself a papal denunciation, which she must

have relished.

A book can do that, capture a time and a spirit, be the expression of a

broad yearning running through society. Read the book and you will

understand Zeitgeist. Sometimes the book will be

one a group strongly identifies with - for example, On the Road,

by Jack Kerouac, among American youth - or, conversely strongly

identifies against - Salman Rushdie's The

Satanic Verses among some Muslims.

So that too is what a book can be, a thermometer revealing a fever.

Yours truly,

Yann Martel

FRANCOISE

SAGAN (1935-2004),born Francoise Quoirez, was a novelist, playwright

and screenwriter. Sagan's novels centre around disillusioned bourgeois

characters (often teenagers) and primarily romantic themes; her work

has been compared to that of J.D. Salinger. The writer Francois Mauriac

described her as "a charming little monster." Her oeuvre includes

dozens of works for print and performance. She suffered a car accident

in 1957, an experience that left her addicted to painkillers and other

drugs for much of her life.

Yann

Martel

Sự lớn

lao của Hemingway không hệ tại nhiều ở điều ông nói mà ông nói điều đó như thế nào. Ông nắm tiếng Anh và viết nó một cách mà trước

đó chưa từng có ai viết. So sánh hai ông, Hemingway, sinh năm 1899 và

Henry James, mất năm 1916, khoảng cách 17 năm giữa họ đó mới ngỡ ngàng,

tương phản làm sao, ở trong văn phong của họ. Với James, sự thực, cái

rất giống, chủ nghĩa hiện thực, hay bất cứ cái từ gì mà bạn muốn gọi,

thì được hoàn thành bằng một thứ tiếng Anh ê hề, đầy ra đó, tha hồ mà

xài. Hemingway, ngược hẳn lại, tước bỏ trong văn phong của ông mọi trò

‘bầy biện cho nó sang, đồ hàng mã, đồ dởm, thùng rỗng kêu to, hoành

tráng, sự lạm dụng tu từ… ‘, và sử dụng những tính từ và trạng từ cho

thơ xuôi của ông, theo cái kiểu mà một tay 'đốc tưa' ghi đơn thuốc cho

một người nghi là bịnh. Hiệu quả là một thứ thơ xuôi cực kiệm từ, với

một nhịp điệu, sự cường tráng, và sự cực giản khiến chúng ta nhớ tới

một bản văn cực kỳ già, cực kỳ cổ xưa: Thánh Kinh.

Từ

những bản văn của Hemingway móc nối tới… Thánh Kinh, đừng nghĩ là tôi

‘cường điệu’.

Hemingway quả là đã thấm nhuần ngôn ngữ và hình ảnh Thánh Kinh, và Ngư

Ông

Và Biển Cả có thể được đọc như là một ám dụ Ky tô, tuy nhiên, tôi

chẳng dám

coi nó là một tác phẩm tôn giáo, hẳn nhiên không phải theo cái kiểu của

cuốn

sách mà tôi vừa mới gửi thủ trưởng hai tuần trước đây, Gilead.

Hemingway

sử dụng những ngày Chúa ghé trọ trần gian theo

cách muôn thuở của riêng ông, để khai triển,

khám phá, thám hiểm ý nghĩa của những khổ đau của con người.

‘Ân

sủng dưới sức ép’ là

chữ của Hemingway, khi bị tra hỏi về sự gan góc, lì lợm của những nhân

vật của

ông. Một cách rất riêng Hemingway để lèm bèm về ‘hoàn tất chiến thắng

qua thất

bại’. Gấu này đã ‘bàng bạc’ nhận ra điều này – và, có thể là do đọc

Hemingway

mà có được – khi phán, Miền Nam có công với lịch sử ‘thông qua sự thất

trận’ của

họ! Tuy nhiên, khi viết như vậy, là Gấu vẫn còn ‘hoang tưởng’ về cuộc

thống nhất

đất nước, cả giống Mít xúm vào xây dựng một cái nhà Mít to đùng, bây

giờ thì ‘ô

hô ai tai’ rồi!

Vinh quang,

chiến thắng thông qua thất bại, nhờ thất bại mà có được, ‘con người có

thể bị

huỷ diệt nhưng không thể bị đánh gục’, cuộc đi câu ‘mang về không

phải con cá mà là bộ xương khổng lồ của nó’, thấm đẫm tinh thần Ky Tô

giáo của

Ông Già Santiago [Gấu Già đó ư?] lạ làm sao, cũng là cuộc phiêu lưu mà

điểm tận

cùng là nhà tù VC của cả một miền đất: Gấu đã chẳng viết về nhà thơ NXT

và tập

thơ nhờ đi tù VC mà có được, về TTT mà những vần thơ ẩn mật của ông,

nhờ té núi

khi vác nứa mà ngộ ra? (1)

(1)

Trong bài phỏng vấn, Thơ Giữa

Chiến Tranh và Trại Tù (đã đăng trên

VHNT), nhà thơ Thanh Tâm Tuyền cho rằng: "làm thơ trong trại cải tạo,

đó

cũng là trở về với thơ ca bình dân. Chế độ lao động trong trại, đó là

một ngày

căng thẳng tám tiếng, không có ngày nghỉ cuối tuần; mỗi tù nhân có

riêng một vũ

trụ: một chiếc chiếu; chừng năm, sáu chục tù trên dưới hai lớp, gói gọn

trong tấm

"toan" trên trăm tù. Viết là một xa xỉ: chỗ ngồi, thời gian viết. Với

nhịp tù hối hả như vậy, cái lạnh, cái đói… ai dám nghĩ đến sáng tạo?

Ngay cả

thiên tài, hay một sức mạnh siêu nhiên cũng không thể vượt qua những

"trói

buộc" này."

"Tuy nhiên người Việt nói, "làm thơ", không

ai nói "viết thơ". Như vậy, người ta có thể làm thơ bất cứ ở đâu

("Thơ ở đâu xa" là tựa đề tập thơ của thi sĩ, sau khi ra tù), trong bất

cứ vị trí nào: đi, đứng, nằm, ngồi, thức. Thơ gặp anh không cần hò hẹn,

không định

rõ ngày giờ… Nó chỉ yêu cầu bạn: hãy giữ tiếng nói chơn chất của mình.

Tiếng

nói này, sau đó, sẽ quyết định cuộc đời của riêng nó".

Những kinh nghiệm làm thơ trong trại tù của thi sĩ làm chúng

ta hiểu được, sự khác biệt giữa những dòng thơ của chính Thanh Tâm

Tuyền, trước

và sau trại tù; giữa "đỉnh cao" của thơ tự do "khi còn tự

do", như trong "Liên Đêm Mặt Trời Tìm Thấy", và của "thơ ở

trong tù" như trong "Thơ Ở Đâu Xa" : nhà thơ hết còn là một vị

phù thuỷ của chữ nghĩa, giản dị chỉ là một tiếng nói chơn chất:

"Trong tôi còn lại chi? Gia đình, bạn bè. Những bài

thơ, chắc chắn rồi, đã được đọc, được ghi thầm. Đúng một lúc nào đó, ký

ức

nhanh chóng bật dậy, đọc, cho mình tôi, những bài thơ. Luôn luôn, ở đó,

bạn sẽ

gặp những tia sáng lạ. Thời gian của điêu tàn làm mạnh thơ ca… cõi thơ

êm đềm

ngự trị bên trên sự bình thản của vũ trụ."

....

Còn những dòng thơ nhẹ nhàng, thanh thoát của Nguyễn Xuân Thiệp,

là do đằng sau ông có cả một đồng đội, cả một chân lý, lẽ phải, chính

nghĩa mà

chỉ khi vào tù ông mới có được.

"Chuyện Kể Năm 2000"

For concerning

Christ, that was the Apostle Paul's momentous insight (some would call

it God's

gift): the possibility of triumph, of salvation, in the very midst of

ruination. It's a message, a belief that transforms the human

experience

entirely.

Về chuyện liên quan tới Chúa

Ky Tô ở đây, đó chính là giây phút

đốn ngộ của

Apostle Paul (có người gọi là quà của Thượng Đế): khả thể về chiến

thắng, về

cứu vớt, ở ngay chính trái tim của điêu tàn. Đó là thông điệp, niềm

tin chuyển

hoá toàn thể kinh nghiệm nhân loại.

Vậy mà ‘ô nhục’

ư?

*

Thời gian của

điêu tàn làm mạnh thơ ca.

Le temps des

ruines renforce la poésie.

Cõi thơ êm đềm

ngự trị ở bên trên sự bình thản của vũ trụ.

Cet état

poétique paisible règne sur le calme

de l'univers.

THANH

TAM

TUYEN: La poésie entre la guerre et le camp

Thơ giữa chiến

tranh và trại tù

Trong khi

suy tư về chuyến đi câu và cuộc gặp gỡ với con K của Gấu Già, tôi bèn

tự hỏi,

liệu có thể có một chiều hướng chính trị, như là Gấu áp dụng vào Miền

Nam VN và

cuộc thất trận của nó, và sau cùng tôi đi đến kết luận, nhảm, làm đếch

gì có tí

chính trị nào trong Ngư Ông Và Biển

Cả!

Trong chính

trị, chiến thắng tìm đến chiến thắng [kẻ thù nào cũng đánh thắng, như

mấy anh

VC từng bốc phét], và thất trận thì chỉ mang đến thất trận dài dài, và

tận cùng

bằng cuộc tháo chạy vĩ đại!

Cái thông điệp của ông già nghèo khổ làm nghề đánh

cá người Cu Ba, của Hemingway thì hoàn toàn riêng tư, cá nhân, nó gửi

tới con

người cá nhân là mỗi một trong chúng ta, chứ không phải những vai trò

mà chúng

ta phải ôm lấy.

Mặc dù hùng vĩ trong dàn dựng, nào biển cả mênh mông, nào

con cá kẻ thù xứng đáng, nào, nào…

Ngư Ông Và Biển Cả, tuyệt vời thay, chỉ là một

tác phẩm rất ư là riêng tư, thầm kín, của… linh hồn.

Và tớ mới

mong ước làm sao: Cầu chúc cho tất cả chúng ta: rằng cái chuyến đi câu,

ra mãi tít

ngoài biển cao, gặp con K rồi trở về, thật là bảnh, thật là hách, thật

là xứng đáng,

như của... Gấu Già Santiago!

Hà, hà!

BOOK 18

METAMORPHOSIS

BY FRANZ

KAFKA

December 10,

2007

To Stephen Harper,

Prime

Minister of Canada,

A cautionary

tale of sorts,

From a

Canadian writer,

With best

wishes,

Yann Martel

Dear Mr.

Harper,

The book

that accompanies this letter is one of the great literary icons of the

twentieth century. If you haven't already read it, you've surely heard

of it.

The story it tells of an anxious, dutiful travelling salesman who wakes

up one

morning transformed into a large insect is highly intriguing, and

therefore

entertaining. The practical considerations of such a change the new

diet, the

new family dynamic, the poor job prospects, and so on are all worked

out to

their logical conclusion. But that Gregor Samsa, the salesman in

question,

nonetheless remains at heart the same person, the same soul, still

moved by

music, for example, is also plainly laid out. And what it all might

mean, this

waking up as a bug, is left to the reader to determine.

Franz Kafka

published Metamorphosis in 1915. It

was one of his few works published while he was alive, as he was racked

by

doubts about his writing. Upon his death in 1924 of tuberculosis, he

asked his

friend and literary executor, Max Brod, to destroy all his unpublished

works.

Brod ignored this wish and did the exact opposite: he published them

all. Three

unfinished novels were published, The

Trial, The Castle and Amerika,

but in my opinion

his many short stories are better, and not only because they're

finished.

Kafka's

life, and subsequently his work, was dominated by one figure, his

domineering

father. A coarse man who valued only material success, he found his

son's

literary inclinations incomprehensible. Kafka obediently tried to fit

into the

mold into which his father squeezed him. He worked most of his life,

and with a

fair degree of professional success, for the Workers' Accident

Insurance

Institute of the Kingdom of Bohemia (doesn't that sound like it's right

out of,

well, Kafka?). But to work during the day to live, and then to work at

night on

his writings so that he might feel alive, exhausted him and ultimately

cost him

his life. He was only forty years old when he died.

Kafka

introduced to our age a feeling that hasn't left us yet: angst. Misery

before

then was material, felt in the body. Think of Dickens and the misery of

poverty

he portrayed; material success was the road out of that misery. But

with Kafka,

we have the misery of the mind, a dread that comes from within and will

not go

away, no matter if we have jobs. The dysfunctional side of the

twentieth

century, the dread that comes from mindless work, from constant,

grinding,

petty regulation, the dread that comes from the greyness of urban,

capitalist

existence, where each one of us is no more than a lonely cog in a

machine, this

was what Kafka revealed. Are we done with these concerns? Have we

worked our

way out of anxiety, isolation and alienation? Alas, I think not. Kafka

still

speaks to us.

Kafka died

seven months into the public life of Adolf Hitler - the failed Munich

Beer Hall

Putsch, in which the ugly Austrian corporal had prematurely tried to

seize

power, took place in November of 1923 - and

there is something annunciatory about the

overlap, as if what Kafka

felt, Hitler delivered. The overlap is sadder still: Kafka's three

sisters died

in Nazi concentration camps.

Metamorphosis

makes for a fascinating yet grim read. The premise may bring a

black-humored

smile to one's face, but the full story wipes that smile away. One

possible way

of reading Metamorphosis is

as a cautionary tale. So much alienation in

its

pages makes one thirst for authenticity in one's life.

Christmas is

fast approaching. I'll see with the next book I send you if I can't

come up

with something cheerier to match the festive season.

Yours truly,

Yann Martel

Franz KAFKA

(1883-1924) was born in Prague, Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), and

is

considered one of the most influential authors of the twentieth

century. Much

of Kafka's work is disturbing, dealing with nightmarish situations and

dark

themes including alienation, dehumanization and totalitarianism, a

literary

style now known as "Kafkaesque." He is best known for his novella Metamorphosis

as well as for two of his novels, The

Trial and The Castle,

which were

published posthumously. He earned a doctorate in law and wrote in his

spare

time, spending most of his working life at an insurance company.

Cuốn sách kèm theo thư này là

một trong những thánh tượng lớn, của

văn chương thế kỷ 20. Nếu thủ trưởng chưa đọc, thì hẳn cũng đã nghe

nói về

nó, chắc chắn như vậy. Câu chuyện cuốn sách kể - về một anh bán hàng

rong âu

lo, khắc khoải, lúc nào cũng không quên bổn phận của mình, một buổi

sáng thức

dậy thấy biến thành một con bọ lớn – thì thật là ly kỳ, và do đó, thú

vị. Những

cân nhắc thực tiễn về một sự thay đổi như thế - chế độ ăn khem, kiêng

mới, động

lực gia đình mới, những viễn tượng liên quan tới cái công việc bán hàng

rong

nghèo, và vv - tất cả đều được tính đếm để đi đến kết luận hợp lý.

*

Three

unfinished novels were published, The Trial, The Castle and Amerika,

but in my opinion his many short stories are better, and not only

because

they're finished

Đúng

y chang Gấu, chỉ đọc được, và chỉ đọc những truyện ngắn của Kafka.

Không làm

sao đọc hết một truyện dài của ông, dù bao phen thử ép xác

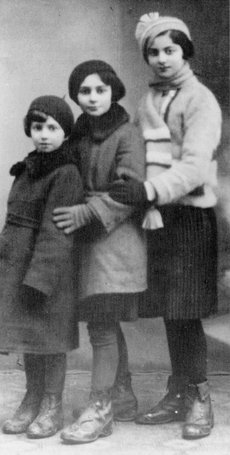

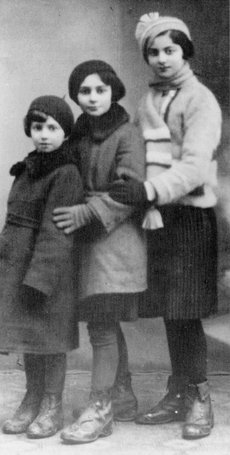

Jews, Poles

& Nazis: The Terrible History

June 24,

2010

by Timothy

Snyd

US Holocaust

Memorial Museum/Miles and Chris Laks Lerman

The sisters

Renia, Rosalie, and Chanka Laks, from a prominent Jewish family in

Wierzbnik,

Poland. Rosalie Laks—whose testimony appears in Christopher Browning’s

Remembering Survival—said that when their father was pushed into a

gutter and

kicked repeatedly by a German during the early days of the Nazi

occupation, ‘This was the

first time I understood what the war was all about.’ All

the sisters survived the war and are still alive

*

Kafka died

seven months into the public life of Adolf Hitler - the failed Munich

Beer Hall

Putsch, in which the ugly Austrian corporal had prematurely tried to

seize

power, took place in November of 1923 - and there

is something annunciatory about the overlap, as if what Kafka

felt, Hitler delivered. The overlap is sadder still: Kafka's three

sisters died

in Nazi concentration camps.

Martel

“This

was the first time I understood what the war was all about.”

Kinh

nghiệm trên, Gấu đã từng trải qua: Lần đầu tiên Gấu thấy người ta đánh

người

ta, và hiểu được ‘thế nào là’ cuộc chiến Quốc Cộng, là cái lần thấy tay

quận

trưởng một quận Tề ở quê Sơn Tây của Gấu, đá vào một tay du

kích

Việt Cộng, bị Bảo Chính Đoàn, tiền thân của

quân lực VNCH, tóm được. Tay quận trưởng đang đá tới tấp, chợt ngước

mắt lên, thấy

cái nhìn khiếp đảm của thằng cu Gấu, bèn ngưng đá, ra lệnh đem tên du

kích đi

chỗ khác, chắc là đem đi giam.

Cái

tay quận trưởng có liên quan tới Gấu. Cũng thê lương lắm, khi nào cảm

thấy bớt thê lương, Gầu sẽ kể tiếp

Bữa đó, Gấu lên đồn, ở ven đê

làng Vân

Xa, quê ngoại của Gấu để học, lớp học do quận trưởng làm thầy giáo.

Sau, đọc

truyện The Guest, của Camus,

là nhớ lại cảnh trên. (1)

(1)

Nhưng cú ‘bức

tử’ Camus, chính là Cuộc Chiến Algérie. Là một

anh Tây

mũi lõ ở thuộc địa, [an Algerian Frenchman], ông bị sức ép của tình yêu

của ông

dành cho thế giới Địa Trung Hải này, và sự dâng hiến mình cho nước

Pháp. Một

khi ông nhìn ra sự giận dữ, Tây mũi lõ hãy cút về nước, và cuộc nổi dậy

hung bạo

từ đó mà ra, ông không thể chọn thái độ chống đối nhà nước của Sartre,

bởi vì

những bè bạn của ông bị giết bởi những người Ả rập - những tên "khủng

bố",

như báo chí Pháp gọi – trong cuộc chiến giành độc lập. Ông đành chọn

thái độ im

lặng. Trong bài ai điếu thật cảm động về người bạn cũ của mình, khi Camus mất, Sartre đã khai triển những chiều sâu nhức

nhối mà Camus giấu kín chúng bằng sự im lặng

đầy cao ngạo, đầy phẩm giá

của ông.

Bị ép buộc phải chọn bên, Camus thay vì chọn,

thì

khai triển ‘địa ngục tâm lý’, trong Người Khách, The Guest.

Truyện ngắn tuyệt hảo mang tính chính trị này diễn tả chính trị, không

như là một

điều mà chúng ta hăm hở vồ lấy nó, theo cái kiểu đường ra trận mùa này

đẹp lắm,

nhưng mà là một tai nạn chẳng sung sướng tí chó nào, mà chúng ta bắt

buộc phải

chấp nhận.

Thật khó mà 'phản biện' ông, về điều này, nhất là Mít chúng ta!

Pamuk: Albert Camus

Nếu có tí mắc míu giữa NNT và

Camus, có thể, là qua truyện ngắn Người Khách.

Câu chuyện một anh giáo làng tại một vùng xôi đậu, ngày Quốc Gia, đêm

VC. Tay

giáo làng này một bữa đang dậy học thì được một ông cảnh sát Ngụy tới

nhờ giữ

giùm một anh VC nằm vùng, trong khi ông ta lên tỉnh xin thêm chi viện,

để giải

giao về tỉnh. Khi ông cảnh sát đi rồi, tay giáo làng bèn cởi trói cho

anh VC

nằm vùng, giúi cho 10 ngày luơng thực [đám sĩ quan Ngụy sau đi trình

diện cải

tạo, phải mang theo 10 ngày lương thực, là do chuyện này mà ra], và chỉ

hướng

trốn vô rừng, không ngờ đúng hướng đó, có Ngụy quân đang nằm sẵn!

Và khi anh giáo làng nhìn lại tấm bảng đen, thì đã có hàng chữ phấn

trắng: Mi

bán chiến sĩ giải phóng cho Ngụy, mi phải thường mạng!

Kafka

mất 7 tháng, sau khi viên cai đội Hitler toan tính nắm quyền lực vào

tháng

11/1923, nhưng thất bại. Có một điềm gở ở 7 tháng dư ra này: như thể

điều mà

Kafka dự cảm thì Hitler phân phối. Quãng thời gian dư thừa còn làm buồn

bã thêm,

khi chúng ta nghĩ tới ba chị em của Kafka, chết trong trại tập trung.

Ui

chao, Gấu lại nghĩ đến Brodsky. Khi ông mất, năm 1996, Tolstaya than

thở, phải

chi ông sống thêm được 4 năm thì thế kỷ 20 đã có một thành tựu vẹn toàn.

Kafka giới

thiệu với thời đại của chúng ta một cảm nghĩ, mà cho dù ông đi rồi, cảm

nghĩ này

vẫn không chịu rời bỏ chúng ta: ‘angst’ [tiếng Đức, tạm dịch bằng những

từ

như âu lo,

xao xuyến, bất an, sợ sệt, anxiety, angoisse…]. Trước đó, sự nghèo khổ,

cơ cực,

misery, thì chỉ xẩy ra trong ‘đời thường’, mang tính vật lý, vật chất.

Hãy nghĩ

tới Dickens, thí dụ, và sự nghèo đói, cơ cực ông miêu tả, và sự thành

công về vật

chất là con đường thoát ra khỏi. Nhưng với Kafka, chúng ta có sự cơ cực

của tâm

hồn, nỗi âu lo, xao xuyến từ bên trong chúng ta hành hạ chúng ta, và

không chịu

bỏ đi, cho dù chúng ta kiếm ra việc làm, hết còn đói khát khổ sở!

Hoá Thân đem đến cho người đọc sự

‘ngỡ ngàng

u ám’, a fascinating yet grim read. Một nụ cười khôi hài đen, nụ cười

biến mất

theo từng trang sách, chỉ còn khuôn mặt méo xệch. Một trong những cách

đọc nó,

là coi đây là như một cảnh báo. Quá nhiều vong thân trên tí ti trang

sách khiến

người đọc khao khát một sự chân thực cho cuộc đời của mình.

Yann

Martel

BOOK 9:

CHRONICLE OF

A DEATH FORETOLD

BY GABRIEL

GARCIA MARQUEZ

August 6, 2007

To Stephen

Harper,

Prime

Minister of Canada,

From a

Canadian writer,

With best

wishes,

Yann Mattel

Dear Mr.

Harper,

When I found

a used copy of the latest book that I'm sending you, I was pleased that

it was

a hard cover - a first after eight paperbacks - but I was disappointed

with the

cover artwork. (1). Surely, Chronicle

of a Death Foretold, the short novel

by the

great Gabriel Garcia Marquez, deserves better than this awkward job.

Who chose

the purple? It's all so hideous. But you can't judge a book by its

cover, isn't

that right?

Which is a

nice way of broaching the topic of cliches.

A cliché, to

remind you, is a worn, hackneyed phrase or opinion. At one time,

perhaps in the

Middle Ages among monks slowly copying books by hand in a monastery,

the notion

that nothing of substance can be judged by its surface, expressed in

terms of a

bound stack of paper and its protective shell, have seemed like a

dazzling

revelation that had the monks looking at each other in amazement and

rushing

out to sing in full-throated worship to

urbi et orbi: "Praise be to

God! A book can't be judged by its cover! Hallelujah, hallelujah!"

But now,

even among people But now, even among people who don't read a book a

year, it's

a cliché, it's a lazy, thoughtless way of expressing oneself.

Sometimes

clichés are unavoidable. "I love you" a sentence that is foundational

to the well-being of every human being, the "you" being another

person, a group of people, a grand notion or cause, a god, or simply a

reflection in the mirror is a cliche. Every actor who has to say the

line

struggles to deliver it in a way that makes it sound fresh, like Adam

saying it

for the first time to Eve. But there's no good way of saying it

otherwise and

no one really tries to. We live very well with "I love you" because

the syntactical simplicity of it one each of subject, verb, object,

nothing

else nicely matches its intended truthfulness. So we happily blurt out

the

cliché, some of us repeating it several times, for emphasis, or some of

us

saying it all the time, for example at the end of every phone call with

a

family member. Lovers at a balcony, sons and daughters at war,

dervishes

whirling they're all living "I love you" in a way that is not clicked

but essential.

But

otherwise clichés should be avoided like the West Nile virus. Why?

Because they

are stale and flat, and because they are contagious. Convenient

writerly

shortcuts, hurried means of signifying "you know what I mean," clichés

at first are just a froth of tiny white eggs in the ink of your pen,

incubated

slowly by the warmth of your lazy fingers. The harm to your prose is

slight,

and people are forgiving. But convenience, shortcuts and hurry are no

way to

write true words, and if you are not careful-and it is hard work to be

careful-the eggs multiply, bloom and enter your blood.

The damage

can be serious. The infection can spread to your eyes,

to your nose, to your tongue, to your ears, to your skin, and worse: to

your

brain and to your heart. It's no longer just your words, written and

spoken,

that are conventional, conformist, unoriginal, dull. Now it's your very

thoughts and feelings that have lost their heartbeat. In the most

serious

cases, the person can no longer even see or feel the work directly, but

can

only perceive it through the reductive, muffling filter of cliché.

At this

stage, the cliché attains its political dimension: dogmatism. Dogmatism

in

politics has exactly the same effect as the cliché in writing: it

prevents the

soul from interacting openly and honestly with the world, with that

pragmatism

that lets in fresh all the beautiful, bountiful messiness of life.

The cliché

and dogmatism two related banes that all writers and politicians should

avoid

if we are to serve well our respective constituencies.

As for the

Garcia Marquez book, I got it for you because of your recent trip to -

and

renewed interest - in Latin America. The man's a genius.

Yours truly,

Yann Martel

GABRIEL

GARCIA MARQEZ (b. 1927) is an internationally acclaimed novelist, short

story

writer, screenplay writer, memoirist and journalist. During his long

literary

career, he has been credited with popularizing the "magical realism"

writing style. Marquez, nicknamed "Gabo," sets his stories in Latin

America and often addresses the themes of isolation, love and memory.

His best-known

works are One Hundred Years of

Solitude and Love in the Time

of

Cholera. He is also well

known for his political activism. He received the Nobel Prize in

Literature in

1982. Raised in Colombia, he now lives

in Mexico City.

*

The cover

features an unappealing drawing of a bride. She looks like a stiff

porcelain

doll.

*

Cách đọc Một

cái chết được báo trước, của Yann Martel, thật lạ, và có vẻ như

chẳng ăn nhập gì

tới câu chuyện của Garcia Marquez, về một thanh niên trong một làng

nhỏ, bị đe

dọa làm thịt, hầu như tất cả mọi người trong làng đều được biết, vậy mà

nó cứ xẩy ra, chẳng

hề có một toan tính ngăn chặn, hoặc cảnh báo, như Gấu đọc đã lâu rồi

còn nhớ được.

Martel cho biết, ông gửi tác phẩm trên cho thủ trưởng Canada, nhân

chuyến đi của

ông này tới khu vực Mỹ Châu La Tinh, và những quan tâm mới của thủ

tướng Canada

về vùng đất này, nhưng liệu đúng như thế?

BOOK 45:

FICTIONS

BY JORGE

LUIS BORGES

December 22,

2008

To Stephen

Harper,

Prime

Minister of Canada,

A book you

may or may not like,

From a

Canadian writer,

With best

wishes,

Yann Martel

Dear Mr.

Harper,

I first read

the short story collection Fictions,

by the Argentina writer Jorge Luis Borges

(1899-1986), twenty years ago and I remember not liking it much. But

Borges is

a very famous writer from a continent with a rich literary tradition.

No doubt

my lack of appreciation indicated a lack in me, due to immaturity.

Twenty years

on, I would surely recognize its genius and I would join the legions of

readers

who hold Borges to be one of the great pens of the twentieth century.

Well,

that change of opinion didn't take place. Upon rereading Fictions I was as

unimpressed this time around as I remember being two decades ago.

These stories

are intellectual games, literary forms of chess. They start simply

enough, one

pawn moving forward, so to speak, from fanciful premises-often about

alternate

worlds or fictitious books-that are then rigorously and organically

developed

by Borges till they reach a pitch of complexity that would please Bobby

Fischer. Actually, the comparison to chess is not entirely right. Chess

pieces,

while moving around with great freedom, have fixed roles, established

by a

custom that is centuries old. Pawns move just so, as do rooks and

knights and

queens. With Borges, the chess pieces are played any which way, the

rooks

moving diagonally, the pawns laterally and so on. The result is stories

that

are surprising and inventive, but whose ideas can't be taken seriously

because

they aren't taken seriously by the author himself, who plays around

with them

as if ideas didn't really matter. And so the flashy but

fraudulent erudition of Fictions. Let me give you one

small

example, taken at random. On page CS of the story "The Library of

Babel," which is about a universe shaped like an immense, infinite

library, appears the following line concerning a particular book in

that

library:

He showed his find to a

traveling decipherer, who told him that the

lines were written in Portuguese; others said it was Yiddish. Within

the

century experts had determined what the language actually was: a

Samoyed-Lithuanian dialect of Guarani, with inflections from classical

Arabic.

A

Samoyed-Lithuanian dialect of Guarani, with inflections from classical

Arabic?

That's intellectually droll, in a nerdy way. There's a pleasure of the

mind in

seeing those languages unexpectedly juxtaposed. One mentally jumps

around the

map of the world. It's also, of course, linguistic nonsense. Samoyed

and

Lithuanian are from different language families the first Uralic, the

second

Baltic-and so are unlikely ever to merge into a dialect, and even less

so of

Guarani, which is an indigenous language of South America. As for the

inflections from classical Arabic, they involve yet another impossible

leap

over cultural and historical barriers. Do you see how this approach if

pursued

relentlessly, makes a mockery of ideas? If idea mixed around like this

for show

and amusement, then they ultimately reduced to show and amusement. And

pursue

approach Borges does, line after line, page after page. His book is

full of

scholarly mumbo-jumbo that is ironic, magical, non-sensical. One of the

games

involved in Fictions is: do you get the references? If you do, you feel

intelligent; if you don't, no worries, it's probably an invention,

because much

of the erudition in the book is invented. The only story that I found

genuinely

intellectually engaging, that is, making a serf thought-provoking

point, was

"Three Versions of Judas,” in which the character and theological

implications of Judas are discussed. That story made me pause and

think. Beyond

the flash, there I found depth.

Borges is often described as a writer's writer.

What this is supposed to mean is that writers will find in him all the

finest qualities

of the craft. I'm not sure I agree. By my reckoning a great book

increases

one's involvement with the world. One seemingly turns away from the

world when

one reads a book but only to see the world all the better once one has

finished

the book. Books, then, increase one's visual acuity of the world. With

Borges,

the more I read, the more the world was increasingly small and distant.

There's

one characteristic that I noticed this time around that I hadn't the

first

time, and that is the extraordinary number of male names dropped into

the

narratives, most of them writers. The

fictional world of Borges is nearly exclusively male unisexual. Women

barely

exist. The only female writer mentioned in Fictions are Dorothy Sayers,

Agatha

Christie and Gertrude Stein, the last two mentioned in "A Survey of

Works

of Herbert Quain" to make a negative point. In “Menard, Author of the

Quixote," there is a Baroness de Bacourt and a Mme Henri Bachelier

(note

how Mme Bachelier's name is entirely concealed by her husband's). There

may be

a few others that I missed. Otherwise, the reader gets male friends and

male

writers and male characters into the multiple dozens. This is not

merely a

statistical feminist point. It hints rather at Borges's relationship to

the

world. The absence of women in his stories is matched by the absence of

any

intimate relations in them. Only in the last story, "The South," is

there some warmth, some genuine pain to be felt between the characters.

There

is a failure in Borges to engage with the complexities of life, the

complexities of conjugal or parental life, or, indeed, of any other

emotional

engagement. We have here a solitary male living entirely in his head,

someone

who refused to join the fray but instead hid in his books and spun one

fantasy

after another. And so my same, puzzled conclusion this time round after

reading

Borges: this is juvenile stuff.

Now why am I sending you a book that I don't

like? For a good reason: because one should read widely, including

books that

one does not like. By so doing one avoids the possible pitfall of

autodidacts,

who risk shaping their reading to suit their limitations, thereby

increasing

those limitations. The advantage of structured learning, at the various

schools

available at all ages of one's life, is that one must measure one's

intellect

against systems of ideas that have been developed over centuries. One's

mind is

thus confronted with unsuspected new ideas.

Which is to say that one learns,

one is shaped, as much by the books that one has liked as by those that

one has

disliked.

And there is also, of course, the possibility that

you may love Borges.

You may find his stories rich, deep, original and entertaining. You may

think

that I should try him again in another twenty years. Maybe then I'll be

ready

for Borges.

In the meantime, I wish you and your family a merry

Christmas.

Yours

truly,

Yann Martel

Jorge Luis

Borges (1899-1986) was an Argentinean poet, short story writer,

anthologist,

critic, essayist and librarian. In his writings, he often explored the

ideas of

reality, philosophy, identity and time, frequently using the images of

labyrinths and mirrors. Borges shared the 1961 Prix Formentor with

Samuel

Beckett, gaining international fame. In addition to writing and giving

speaking

engagements in the United States, Borges was the director of the

National

Library in Argentina, ironically gaining this position as he was losing

his

eyesight.

|