|

|

V/v

Schulz. Trong Inner Workings,

Coetzee đưa ra một hình ảnh thật thần kỳ về

Schulz, người nghệ sĩ "trưởng thành trong thơ ấu", 'mature into

childhood'. Trên Người Nữu Ước, 8 & 15, June, 2009, có bài

viết Giai thoại về Schulz, Bruno Schulz's legend,

thật tuyệt, của David Grossman. Tay này là tác giả cuốn Viết trong bóng tối, Tin Văn đã

từng giới thiệu. Ông cũng đã từng đăng đàn diễn thuyết chung với DTH

tại Nữu Ước.

Cái chết của Schulz cũng là một giai thoại, nhưng thê lương vô cùng,

qua kể

lại của Grossman, trong Viết trong

bóng tối. Ông đi tù Lò Thiêu, nhờ tài vẽ, được một tay sĩ quan

Nazi bảo bọc, khiến một tay sĩ quan Nazi khác ghét, và sau cùng giết

ông, rồi kể lại cho tay kia nghe. Tay kia xua tay, chuyện lẻ tẻ, để

kiếm đứa khác, thế!

*

LIFE AND

LETTERS

THE AGE OF

GENIUS

The legend

of Bruno Schulz.

BY DAVID

GROSSMAN

An afternoon

in spring, Easter Sunday, 1933. Behind the reception desk of a small

hotel in

Warsaw stands Magdalena Gross. Gross is a sculptor, and her modest

family hotel

serves as a meeting place for writers and intellectuals. In the hotel

lobby

sits a Jewish girl of about twelve, a native of Lodz. Her parents have

sent her

to Warsaw for a school holiday. A small man, thin and pale, enters the

hotel,

carrying a suitcase. He is a bit stooped, and to the girl-her name is

Jakarda

Goldblum-he seems frightened. Gross asks him who he is. "Schulz," he

says, adding, "I am a teacher, I wrote a book and I-"

She

interrupts him. 'Where did you come from?"

"From

Drohobycz."

"And

how did you get here?"

"By

train, by way of Gdanski Bridge." The woman teases him. "Tanz?

You are a dancer?"

'What? No,

not at all." He flinches, worries the hem of his jacket. She laughs

merrily, spouting wisecracks, winking past him at the girl.

"And

what exactly are you doing here?" she asks finally, and he whispers,

"I am a high-school teacher. I wrote a book. Some stories. I have come

to

Warsaw for one night, to give it to Madame Nalkowska." Magdalena Gross

snickers, looks him up and down. Zofia Nalkowska is a renowned Polish

author

and playwright. She is also affiliated with the prestigious publishing

house Roj.

With a little smile, Gross asks, "And how will your book get to Madame

Nalkowska?"

The man

stammers, averts his eyes, yet he speaks insistently: Someone has told

him that

Madame Gross knows Madame Nalkowska. If she would be so kind-

And when he

says this Magdalena Gross stops teasing him. Perhaps-the girl

guesses-this is

because he looks so scared. Or perhaps it's his almost desperate

stubbornness.

Gross goes to the telephone. She speaks with Zofia Nalkowska and tells

her

about the man. "If I have to read the manuscript of every oddball who

comes to Warsaw with a book," Nalkowska says, "I'll have no time for

my own writing.".

It Magdalena

Gross asks that she take one quick look at the book. She whispers into

the

phone, "Do me a favor. Just look at the first page. If you don't like

it,

tell it him and erase the doubt from his heart."

Zofia Nalkowska

agrees reluctantly. Magdalena Gross hangs up the phone. "Take a taxi.

In

half an hour, Madame Nalkowska will see you, for ten minutes."

Schulz

hurries out. An hour later, he returns. Without the manuscript. "What

did

she say?" Magdalena Gross asks.

He says,

"Madame Nalkowska asked me to read the first page to her out loud. She

listened. Suddenly she stopped me. She asked that I leave her alone

with the

pages, and that I return here, to the hotel. She said she would be in

touch

soon."

Magdalena Gross brings him tea, but he can't drink it. They wait in

silence.

The air in the room grows serious and stifling. The man paces the lobby

nervously, back and forth. The girl follows him with her eyes. Years

later,

after she has grown up, she will leave Poland, go to live in Argentina,

and

take the name Alicia. She will become a painter there and marry a

sculptor,

Silvio Giangrande. She will tell this story to a newspaper reporter

during a

visit to Jerusalem, nearly sixty years after the fact.

The three

wait. Every ring of the telephone startles them. Finally, as evening

draws

near, Zofia Nalkowska calls. She has read only thirty pages, there are

things

that she is certain she has not understood, but it seems to be a

discovery-perhaps

the most important discovery in Polish literature in recent years. She

herself

wishes to have the honor of taking this manuscript to the publisher.

The girl

looks at the man: he seems about to faint. A chair is brought to him.

He sits

down and holds his face in his hands.

Of the many

stories, legends, and anecdotes about Bruno Schulz that I have heard

over the

years, this one especially moves me. Perhaps because of the humble

setting of

this dazzling debut, or perhaps because it was recounted from the

innocent

vantage of a young girl, sitting in the corner of the lobby, watching a

man who

seemed to her as fragile as a child.

And another

story I heard: Once, when Schulz was a boy, on a melancholy evening his

mother,

Henrietta, walked into his room and found him feeding grains of sugar

to the

last houseflies to have survived the cold autumn.

"Bruno,"

she asked, "why are you doing that?"

"So

they will have strength for the winter."

Bruno Schulz, a Polish Jewish

writer, was born in 1892 in the town of Drohobycz,

in Galicia, which

was then

within the Austro- Hungarian Empire and today is in Ukraine.

His oeuvre is small: only

two collections of stories survive, and a few dozen essays, articles,

and

reviews, along with paintings and drawings. But these pieces contain an

entire

world. His two books-"Cinnamon Shops" (1934; the English translation

is titled "The Street of Crocodiles") and "The Sanatorium Under

the Sign of the Hourglass" (1937)-create a fantastic universe, a

private

mythology of one family, and are written in a language that brims with

life, a

language that is itself the main character of the stories and is the

only

dimension in which they could possibly exist. Schulz also worked on a

novel

called 'The Messiah," which was lost during the war. No one knows what

was

in it. I once met a man to whom Schulz had shown the opening lines.

What he

read was a description of morning rising over a city. Light growing

stronger.

Towers and steeples. More than that, he did not see.

On the publication of his

first book, Schulz was immediately recognized as a rare talent by the

Polish

literary establishment. Over the years, he has become a figure of great

interest to readers and writers worldwide. Authors such as Philip Roth,

Danilo

Kis, Cynthia Ozick, and Nicole Krauss have written about him, made him

a character

in their books, or reinvented his life story. An aura of wonder and

mystery

hovers ceaselessly over his works and his biography. "He was one of

those

men on whose head God lays His hand while they are asleep so that they

get to

know what they don't know, so that they are filled with intuitions and

conjectures,

while the reflections of distant worlds pass across their closed

eyelids"

so wrote Schulz about Alexander the Great, in his story "Spring" (as

translated by Celina Wieniewska), But one could easily say the same of

Schulz.

And per' haps also of us, his readers, as his stories: work their way

into our

mind.

It seems that everyone who

loves Bruno Schulz has his own personal

tale of discovery. It happened to me just after published my first

novel,

"The Smile of the Lamb." A new writer is sometime like a new baby in

the family. He arrives from the unknown, and his family has to find a

way to

connect with him, to make him a little less "dangerous" in his newness

and mystery. The relatives lean over the infant's crib, peer at him

closely, and

say, "Look, look, he has Uncle Jacob's nose! His chin is exactly like

Aunt

Malka's!" Something similar happens when you first become an author.

Everyone rushes to tell you who has influenced you, from whom you have

learned,

and, of course, from whom you have stolen.

One day, I received a

telephone call from a man named Daniel Schilit, a Polish Jew who had

come to

live in Israel.

He had read my book, and he said, "You obviously are greatly influenced

by

Bruno Schulz."

I was young and polite and

didn't argue with him. The truth is that, up to that moment, I had not

read a

single story by Schulz. But, after the phone call, I thought I should

try to

find one of his books. And that very evening, at the home of friends, I

happened to come across a Hebrew edition of his collected stories. I

borrowed

it and read it. I read the whole book in several hours. Even today it

is hard

for me to describe the jolt that ran through me.

When I got to the end of the

book, I read the epilogue, by one of Schulz's Hebrew translators, Yoram

Bronowski. And there, for the first time, I came upon the story of how

Schulz

had died:

"In the Drohobycz ghetto

Schulz had a protector, an S.S. officer who had exploited Schulz to

paint

murals on the walls of his house. The rival of this S.S. officer shot

Schulz in

the street in order to provoke the officer. According to rumor, when

they met

thereafter, one told the other, 'I have killed your Jew,' and received

the

reply: 'All right, now I will go and kill your Jew.'''

I closed the book. I felt as

if I had been bludgeoned. As if I were falling into an abyss where such

things

were possible.

Not always can a writer

pinpoint the moment at which a book sprouted inside him. After all,

feelings

and thoughts accumulate over a period of years, until they ripen and

burst out

in the act of writing. And yet, although for many years I had wanted to

write

about the Shoah, it was those two sentences, this devastating sample of

Nazi

syntax and world view-"I have killed your Jew," "All right, now

I will go and kill your Jew” -which were the final push, the electric

shock

that ignited the writing of my novel "See Under: Love."

Schulz's many admirers know

the story that I just told about the circumstances of his death. The

Polish

author and poet Jerzy Ficowski, one of the greatest scholars of

Schulz's life

and work, recounts in his book "Regions of the Great Heresy" how, a

short time before the Black Thursday massacre in Drohobycz, in 1942,

the

Gestapo officer Felix Landau shot a Jewish dentist named Low, who had

been

under the "protection" of another Gestapo officer, Karl Gunther.

There had been a grudge between Landau and Gunther for some time, and

the

murder incited Gunther to take revenge. Proclaiming his intentions, he

went

looking for Schulz, aJewwho had been under Landau's protection. Taking

advantage of the Black Thursday Aktion, he shot Schulz at the corner of

Czacki

and Mickiewicz Streets. "According to acccounts of several Drohobycz

residents," Ficowski writes, "when meeting Landau, Gunther announced

triumphantly: 'You killed my Jew-I killed yours.'''

This is the canonical version

of the story. But there are some who believe that although Schulz was

indeed

killed in the Drohobycz ghetto, that horrible exchange was fabricated,

a

legend. The debate about Schulz's death has endured for decades.

Apparently,

there is no way to settle the issue-nor do I expect that other

'evidence, such

as the testimony that I am about to report, will lay the matter to rest.

From the time I knew that I

was going to be a writer, I also knew that I would write about the

Shoah. And,

as I grew older, I became even more convinced that I would not truly be

able to

understand my life in Israel,

as a person, as a father, a writer, an Israeli, a Jew, until I

understood the

life that I hadn't lived-in the time of the Shoah, in the space of the

Shoah. I

wanted to find out what there was in me that I could have used to

oppose the

Nazis' attempt at erasure. How would I have preserved my human spark

within a

reality that was wholly devised to extinguish it?

Today, I can say that

Schulz's writing showed me a way to write about the Shoah, and, in a

sense,

also a way to live after the Shoah. Sometimes there are such moments of

grace:

you open a book by an author you don't know, and suddenly you feel

yourself

passing through a magnetic field that sends you in a new direction,

setting off

eddies that you'd barely sensed before and could not name. I read

Schulz's

stories and felt the gush of life. On every page, life was raging,

exploding

with vitality, suddenly worthy of its name; it was taking place on all

layers

of consciousness and sub consciousness, in dreams, in illusions, and in

nightmares.

I felt the stories' ability to revive me, to carry me beyond the

paralysis and

despair that inevitably gripped me whenever I thought about the

Holocaust or

came into contact with the aspects of human nature which had ultimately

allowed

it to happen.

In his story "Tailors'

Dummies," Schulz wrote about his father, a cloth merchant:

It is worth noting how, in

contact with that strange man, all things reverted, as it were, to the

roots of

their existence, rebuilt their outward appearance anew from their

metaphysical core, returned

to the primary idea, in order to betray it at some point and to turn

into the

doubtful, risky and equivocal regions which we shall call for short the

Regions

of the Great Heresy.

There is no more precise

description of Schulz's writing itself, of his incessant search for the

"metaphysical core" of things, but also of his brave capacity to

change his point of view in an instant, and to turn, at the very last

second,

in the most ironic and ambiguous way, to the Regions of the Great

Heresy.

This is the strength of this

writer, who has no illusions about the arbitrary, chaotic, and random

nature of

life yet is nonetheless determined to force life - existence both

indefinite

and indifferent - to surrender, to open itself wide and expose the

kernel of

meaning hidden in its depths. I would even add: the kernel of humanity.

But although Schulz is a big

believer in some significance or meaning or law that generates and

regulates everything

in the world-people, animals, plants, even inanimate objects, to which

he often

also grants, with a certain smile, souls and desires-he is still able

to uproot

himself suddenly from this faith and deny it absolutely, with a sort of

bottomless, demonic despair, which only intensifies our sense of his

profound

loneliness and our intuition that, for this man, there was no

consolation in

the world.

In an old-age home in the

southern Israeli city of Beersheba,

in the early summer of2008, I met Ze’ev F1eischer. A short man, slight

and

bald, with huge eyeglasses, he was, at eighty-three, sharp minded,

ironic, and

disillusioned, and his humor was seasoned with bitterness. Most of all,

he was

self-effacing, never missing an opportunity to diminish or make fun of

himself.

He liked to write "satirical songs and fleeting aphorisms," and had

collected his works in a book, entitled "Above My Sailboats." In his

youth, for two years, from 1939 to 1941, Fleischer had been a pupil of

Bruno

Schulz's at the Sternbach Gymnasium, a private high school for Jews, in

Drohobycz. It was situated on Szaszkiewicz Street, not far from

the city center.

"Officially, Schulz was

a teacher of arts and crafts," Fleischer told me. "He was very shy

and bottled up. His stock was very low, in the eyes of others, of

strangers.

"Why? Because a man, after all, has to earn money! And someone like

Schulz, who wrote 'nonsense,' counted for nothing. At most they

regarded him as

human sawdust. . . . His friends, mostly literary people, arranged a

job for

him at the Gymnasium. They, the friends, saw his talent and his

genius-this was

after the publication of his books. They saw that he had no chance of

surviving

in a climate that valued only money, and they decided to help him.

"He was supposed to

teach us drawing and handicrafts, but he understood very quickly that

as an art

teacher he would get no respect from the students. In general, he was

one of

those people who kind of apologize for their very existence, so you can

only

imagine what went on during his lessons. In Schulz's class, there were

mainly

kids who were disciplinary problems, and he knew he would be fresh meat

for

them and their ridicule, and I think he realized very fast that he

could save

himself only if he did something different. So he had this brilliant

idea-he

would tell us stories. Extemporaneous stories, on the spot, and that's

what he

did, and it was like he was painting with words. He told stories, and

we

listened-even the wildest animals listened."

Fleischer laughed. "He

did nearly nothing else. I don't think he drew one line on the

blackboard the

whole year .... But he told stories. He would come into the classroom,

sit

down, then suddenly stand up and start walking around, talking, with

hand gestures,

with that voice of his, and the wildest kids sat there enchanted."

I asked what kind of voice

Schulz had.

"When he spoke softly,

he would dominate. There were no imperatives in his voice. And there

was always

this feeling that he himself was hearing-how do I put it?-that this was

a kind

of music for him. He spoke in a monotone, but colorfully. He didn't

care about

commas or question marks. But he was very impressive. His quiet was

very

impressive. His music was in the quiet. And we, the students, adjusted

ourselves to this quiet. Apparently, he didn't know how to talk loud.

"And he was afraid of

us," Fleischer added. "He was always in a sort of defensive position

.... Because most of the students, they saw him as a lemech,

a nebbish, but, when he told stories, that shut them up.

They didn't understand much, but they felt him. I don't know if he ever

wrote

any of those stories down. I can't recall them specifically. But I

remember

that they were stories not from this world they were mystical. After

the war, I

called up a friend who had studied with me there in the Gymnasium, and

he

didn't remember Schulz at all. But on me Schulz made an impression-I

guess

because of certain feelings of inferiority, which I still have to this

day, and

he, Schulz, also had, and this was a connection between us.

"I also knew Schulz

because he lived across from my aunt on Bednarska Street," Fleischer went

on. "He was my father's age. Older than me by thirty-three years. When

he

was our teacher, I couldn't control myself, and I would run after him

at the

end of the lesson: 'Professor!'-that's what we called all our

teachers-and I

would ask him what he had meant in a story he'd told us, and he would

stop and

talk to me, talk to me like we were equals. Even though they were

already

calling him one of the giants of Polish literature. His lack of

self-confidence

was so obvious. He would walk into class: 'Sorry I came,' 'Sorry I'm

breathing,' a character like that, walking bent over, there was always

that

stooped element in him.

"His sense of humor was

laughing at himself ... When he would start to tell a story, there

would be a

moment when he wasn't sure of himself, always at the beginning, but as

soon as

he started to spin out the story, and saw that the class was quieting

down,

suddenly there would be this smile on his face, half ironic. Now

they're

listening, they're sitting down, nobody is moving. And then this smile

of his,

it was ... like he was celebrating his temporary victory, but at the

same time

he was also kind of laughing at himself."

In my book "See Under:

Love," Bruno Schulz appears both as himself and as a fictional

character.

In his fictional guise, I smuggled him out of wartime Drohobycz, under

the

noses of the literary scholars and the historians, to the pier in Danzig, where he jumped into the water and

joined a

school of salmon.

Why salmon?

Perhaps because salmon have

always seemed to me the living incarnation of a journey. They are born

in

freshwater rivers or lakes. They swim there for a while, and then head

for salt

water. In the sea, they travel in huge schools for thousands of miles,

until

they sense some inner signal, and the school reverses direction and

begins to

return home, to the place where its members were hatched. Again the

salmon swim

thousands of miles. Along the way, they are preyed upon by other fish,

by

eagles and bears. In dwindling numbers, they scoot upriver and leap

against the

current, through waterfalls twenty or thirty feet long, until the few

that

remain reach the exact spot where they were spawned, and lay their

eggs. When

the babies hatch, they swim over the dead bodies of their parents. Only

a few

adult salmon survive to perform the journey a second time.

When I

first heard about the

life cycle of salmon, I felt that there was something very Jewish about

it:

that inner signal which suddenly resonates in the consciousness of the

fist, bidding

them to return to the place where they were born, the place where they

were

formed as a group. (There may also be something very Jewish in the urge

to

leave that homeland and wander all over the world-that eternal journey.)

But there was something else

as well that drove me to choose salmon, something deeply connected with

the

writings of Bruno Schulz. Reading his works made me realize that, in

our

day-to-day routines, we feel our lives most when they are running out:

as we

age, as we lose our physical abilities, our health, and, of course,

family

members and friends who are important to us. Then we pause for a

moment, sink

into ourselves, and feel: here was something, and now it is gone. It

will not

return. And it may be that we understand it, truly and deeply, only

when it is

lost. But when we read Schulz, page by page, we sense the words

returning to

their source, to the strongest and most authentic pulse of the life

within

them. Suddenly we want more. Suddenly we know that it is possible to

want more,

that life is greater than what grows dim with us and steadily fades

away.

When I wrote the

"Bruno" chapter of my book, and described an imaginary scenario in

which Bruno flees the failure of civilization, the perfidious language

of

humans, and joins a school of salmon, I felt that I was very close to

touching

the root of life itself, the primal, naked impulse of life, which

salmon seem

to sketch in their long journey, and which the real Bruno Schulz wrote

about in

his books, and for which he yearned in every one of his stories: the

longed-for

realm that he called the Age of Genius. The Age of Genius was for

Schulz an age

driven by the faith that life could be created over and over again

through the

power of imagination and passion and love, the faith that despair had

not yet

overruled any of these forces, that we had not yet been eaten away by

our own cynicism

and nihilism. The Age of Genius was for Schulz a period of perfect

childhood,

feral and filled with light, which even if it lasted for only a brief

moment in

a person's life would be missed for the rest of his years.

"Did the Age of Genius

ever occur?"

Schulz asks, and we, his

readers, ask along with him. Was there ever really an age of sublime

inspiration, when man could return to his childhood? When mankind could

return

to its childhood? An age when a primeval river of life, of vitality, of

creativity, gloriously raged? An age when essences had not frozen into

forms,

when everything was still possible and plentiful and nascent?

Did the Age of Genius ever

occur?

Schulz wonders. And, if it

did, would we recognize it, answer its secret call? Would we dare to

relinquish

the elaborate defense mechanisms that we have constructed against the

antediluvian wildness and volcanic abundance of such an age, defenses

that

have, bit by bit, become our prison?

A few years after Schulz wrote

that line came an age that was the utter opposite. An age of slaughter.

Of

massive, faceless destruction. And yet to that terrifying call many

responded,

so many, with depressing eagerness.

In "See Under:

Love," I struggled to bring to life, if only for a few pages, the Age

of

Genius, as Schulz had suggested it in his writings. I wrote about an

age in

which every person is a creator, an artist, and each human life is

unique and

treasured. An age in which we adults feel unbearable pain over our

fossilized

childhoods, and a sudden urge to dissolve the crust that has congealed

around

us. An age in which everyone understands that killing a person destroys

a

singular work of art, which can never be replicated. An age in which it

is no

longer possible to think in a way that will produce such sentences as

"I

have killed your Jew"; "Now I will go and kill your Jew."

Stalin once said, "One

death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic." When I read the

stories of Bruno Schulz, I can feel in them-and in myself-the ceaseless

pounding of an impulse to defy that statement, an impulse to rescue the

life of

the individual, his only, precious, tragic life, from that

"statistic."

And also, of course-need one

say this at all?-the urge to rescue, to redeem, the life and death of

Schulz

himself.

'We owe the sole eyewitness

account of Schult s murder in the ghetto of Drohobycz on November

19,1942, to a

fellow-townsman, Izydor Friedman, who survived this particular

butchery,"

Jerzy Ficowski writes, in his book "Letters and Drawings of Bruno

Schulz," which appeared in English in 1988. Ficowski quotes Friedman,

who

escaped the Nazi horrors thanks to forged documents: "I was a friend of

his before the war and remained in close contact with him to the day of

his

death in the Drohobycz ghetto. As a Jew, I was assigned by the

Drohobycz Judenrat to work in a library under

Gestapo authority, and so was Schulz. This was a depository made up of

all

public and the major private libraries .... Its core collection was

that of the

Jesuits of Chyrow. It comprised circa 100,000 volumes, which were to be

catalogued or committed to destruction by Schulz and myself. This

assignment

lasted several months, was congenial and full of interest to us, and

was paradise

by comparison with the assignments drawn by other Jews."

Friedman's meaning is

perfectly clear, of course, but it is hard for me to believe that

Schulz was

indifferent to the significance of the job that had been imposed on

him, to the

cruel irony that he was the man sentenced to decide which books would

be saved

and which would be destroyed.

Friedman continues, 'We spent

long hours in conversation. Schulz informed me at the time that he had

deposited all his papers, notes, and correspondence files with a

Catholic

outside the ghetto. Unfortunately he did not give me the person's name,

or

possibly I forgot it. We also discussed the possibility of Schulz

escaping to Warsaw.

Friends ... had

sent him a [false] identity card from Warsaw.

I provided him with currency and dollars, but he kept putting off the

departure

day. He could not summon up the courage and meant to wait until I

received

'Aryan' papers.

"On a date I don't

recall, in 1942, known as Black Thursday in Drohobycz, the Gestapo

carried out

a massacre in the ghetto. We happened to be in the ghetto to buy food

.... When

we heard shooting and saw Jews run for their lives, we took to flight.

Schulz,

physically the weaker, was caught by a Gestapo agent called Gunther,

who

stopped him, put a revolver to his head, and fired twice.

"During the night, I

found his body, searched his pockets, and gave his documents and some

notes I

found there to his nephew Hoffman-who lost his life a month later.

Toward

morning, I buried him in the Jewish cemetery. I was unable to identity

his grave

site after the liberation of Drohobycz in 1944." (In his book a

"Drohobycz,

Drohobycz," the Polish Jewish writer Henryk Grynberg points out that it

would have been difficult for Friedman to single-handedly bury Schulz's

body.)

According to Ficowski,

Friedman's is the only eyewitness testimony of the murder of Schulz

available.

I thought so, too, until, in the middle of the conversation at the

old-age home

in Beersheba,

Ze'ev Fleischer told me the following:

"In '42 there was an Aktion that lasted a full month.

Generally, an Aktion would go on for

a day or two. The Germans would catch their quota of Jews, and it was

over. But

that time, four weeks. At night it was quiet, and in the daytime they

went

hunting. I was working then at forced labor, in the oil refineries. At

5 A.M.

everyone had to show up in front of his house, and from there we went

to work

until seven at night. At that time we had agreed with my mother that

she would

go into hiding at a place where my uncle worked as a pharmacist.

"And so from the day the Aktion started I didn't see

her. I

lost contact with her, and I went to look for her. I was very tied to

her, and

I decided, against all logic, somehow to get to the place where I

thought I

would find her. And on the way I saw how groups of Germans would see

here and

there a Jew, or some Jews, and shoot them. This wasn't an Aktion

where they rounded up Jews to be sent away. This was murder

on the spot. They simply looked for any Jew, anywhere, and shot him.

Look-today, they call us heroes. Some heroes! We were mice, most of us.

We hid

in our holes.

"Drohobycz is a small

town, and between the houses, also inside the houses, the hunting went

on, and

on the way I saw groups of Germans, and with every group there was also

one

Jew, who worked in the Ordnungsdienst, which was sort of an auxiliary

force to

preserve order, and their people were armed with clubs, not guns.

"And suddenly I heard

shots. I stood by a wall and waited for it to be over. And then I saw a

group of

Jews, two or three Jews, walking past a house, this was on Czacki

Street, and

some Germans and Ukrainians with guns were also there, and they shot at

the

Jews, and the Jews fell down.

"I waited for the

Germans to go away, and then I walked past the dead people. There were

dead

bodies everywhere. Dead people in the street was an everyday thing. If

you saw

the dead body of a cat in the street it would have made a bigger

impression. I

didn't notice that anything special had happened, and I also didn't

know who

they were. I almost walked right past that one dead man, but when I saw

the

bread I drew closer.

"I saw, from one of the

bodies lying on the sidewalk, something like a piece of bread. It was

sticking

out there, from the pocket of his trench coat. I went over to this dead

man,

and I guess I wanted to take his bread. And the dead man turned over. I

turned

him over, and the way I turned him he was facing me, and I look and see

that

it's Schulz. It was Schulz’s face."

Fleischer stopped, folded his

hands on his head, took a few deep breaths.

"And then what did you

do?" I asked. "I can't tell you ... it was something shocking, so

much that I'm not sure that ... what did I do? My instinct was to take

the

bread and run away. And it seems I didn't do that. It seems I didn't do

it.

Look, a person who doesn't eat-and we, after all, didn't eat, we ate

inedible

things, we ate soup that was mostly water with some grass or something

.... And

here I see, in his coat-it looked like, like a serious piece of bread.

And 1

went over to this dead man, and apparently 1 wanted to take the bread

from him. I wanted to pull out the bread and go. I even thought, I'll

come to 1mma with

bread, how , happy she will be, but 1 ... you know, 1 can't ... 1 don't

know

what 1 did with , that bread. 1 think 1 left it. Yes. 1 left be- 1

cause 1 saw

his face, with blood here and , here." Fleischer pointed to his

forehead,

his eyes, covered his whole face with his .., hand. "1 kept running,

and

by the end f of the day 1 found my mother."

"Did you recognize

Schulz immediately, the moment you saw his face?"

"Sure. First of all, he

had a very typical r face. He had this nose ... he looked a little like

a

mouse. But he had a high forehead, and this 1 always would notice

because my

parents would say that a person with a high forehead was very smart."

"Do you remember what

you felt when you saw that the dead man was Bruno Schulz?"

"I felt a chill and I

felt afraid .... You understand by now that he was more than a teacher

for me.

I felt a special kind of connection with him; he was a spiritual

relative in

certain respects. I also felt that my personality was a little similar

to his

... hesitant, bashful, my lack of self-confidence. When they all

laughed at

him, I felt so sorry for him. I completely identified with him. And I

always

admired him, for the way he would talk and we would see a picture. We

could

smell the things he described. I remember how, for example, he

described the

smell of cinnamon, which was dominant in the commercial area of

Drohobycz, and

I, all my life, never could stand the smell of cinnamon, but only when

he

described it I loved it. ... And suddenly I see him dead. I was about

seventeen

at the time, and I had already seen many dead, but suddenly-him."

I asked Fleischer if he knew

the story of Schulz's murder.

"Of course. It was a big

rivalry between two of them. Landau was his patron, and there’s a

version

that's hard for me to accept-those who say Gunther killed him. It's

hard for me

to accept, you know why? Because Gunther was an officer in the Gestapo.

So I

can't quite imagine Gunther running in the street to kill him. He could

have

killed him other ways. No, regarding this question I have no idea. I

have no answer

till this day. There's a million stories I heard."

In the days following my

meeting with Fleischer, I found myself returning in my mind, again and

again,

to the picture of the boy leaning over the body of his beloved teacher

on the

street, and the bread peeking from the dead man's jacket pocket.

Something in

the way Fleischer had spoken about the event wouldn't leave me alone. I

asked

him if he would agree to tell me one more time the story of those

moments. To

my surprise, he readily repeated for me what he remembered.

"He, the dead man, lay

on his side in a way that you couldn't see his face. He lay bent over

like

this-" demonstrated with his body, and I thought of Bruno Schulz lying

stooped over, just as he was in life. "And I also noticed that he had

these shoes, tennisowki, tennis shoes

... "

F1eischer spoke again about

the bread.

"It was a loaf of bread.

Like a brick ... more mud than bread. Half of it was sawdust. It was

like a

piece of mud they used to bake then. If! stuck in a finger, it would go

in like

it was modeling clay."

And what happened then? I

asked. "What happened? ... I took it.

Maybe I took a bite of it?

No. No .... Anyway, I can't tell you clearly what exactly happened with

that

bread."

I told him that what he'd

faced at that moment seemed to me more terrible than any possible

answer to the

question of whether he took or didn't take the bread; I also said I was

sure

that Schulz would have been happy to know that it was his student who

had taken

his bread.

Fleischer nodded, but

couldn't agree with me wholeheartedly. Then he said, "I think I ate.

Very

little. Two or three bites. Not more. Then it broke in half in my hand.

I

wanted to run away." I asked if he had also taken some of the bread to

his

mother, and he said that he didn't remember. "Apparently, yes. Maybe

not.

... But even if! had brought it to her I wouldn't have told her from

where. At

that time we didn't talk much."

I said to Fleischer that I

wanted with all my heart to believe that he had indeed eaten the bread

of Bruno

Schulz, that there had been such a moment between them. He shrugged and

said,

"I don't know. I'm not sure. It was one of those things that are

impossible to remember." And he sighed. "It was horrible, the whole

thing, from beginning to end, and in those days I thought mostly about

my

mother and my father and about myself. Only afterward it came back to

me. After

the war. I dreamed a series of dreams, for a year or two, about friends

of mine

walking in a line and not wanting to talk to me. Turning their backs on

me

because I stayed alive and didn't help them. I felt that this was my

sin. I

still feel that way now."

Fleischer met Jerzy Ficowski,

the biographer of Bruno Schulz, in 2003, in Poland, when they were

interviewed

for a television documentary. He told Ficowski his story but asked that

it not

be published, lest the myth of Schulz's death be spoiled. Ficowski

replied that

Fleischer could think it over, and then talk to him again. But they

didn't meet

again, and Ficowski died in 2006. "My thinking about myths has changed

since then," Fleischer told me. "Again and again I discover myths

that were broken and ideals that were shattered. The story must be

told."

The description of Schulz's

murder as reported by his friend Izydor Frieddman is different, of

course, from

Fleischer’s description. I do not know which of the two is accurate,

and it is possible

that the definitive facts will I never be confirmed. From where

Fleischer stood

during the shooting he likely wouldn't have seen exactly what was

happening,

and he himself says that he was not paying special attention at the

moment of

the killing. There is no reason to doubt his word about what he went

through

when he found himself crouching over the dead body of his teacher.

Fleischer's testimony

provides us with the story of one more human contact with Bruno Schulz,

after

his death and before his body was buried. Contact that for a moment

redeemed

him from the anonymity of the murder, and also from that vile

"statistic," and gave him back his name, his face, and his

uniqueness. This brief contact echoed everything that had been good and

nourishing and generous in him toward his young student. This contact

"allowed" Bruno Schulz to perform one more act of grace, even after

his death.

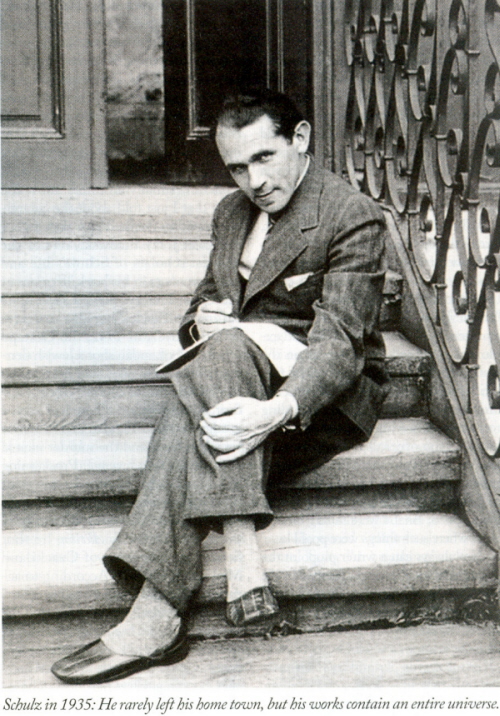

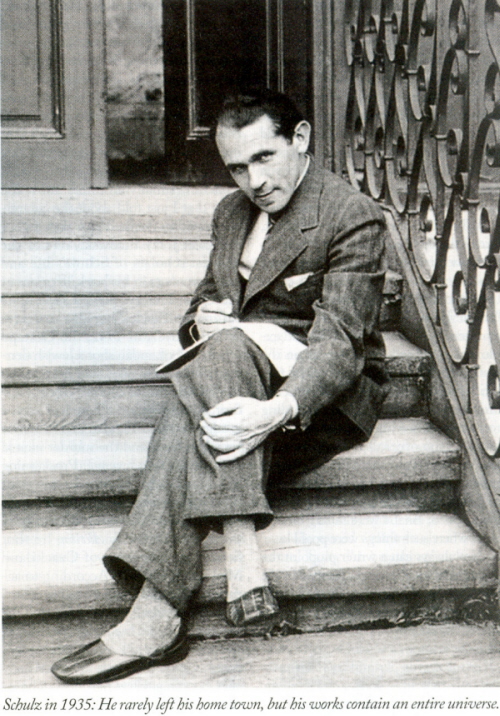

In recent years, I've been

going back, more or less once a year, to the stories of Bruno Schulz.

For me

it's a sort of annual tune-up, a strengthening of the antibodies

against the

temptations of apathy and withdrawal. Every time I open his books, I am

amazed

anew to discover how this writer, a single human being who rarely left

his home

town, created for us an entire world, an alternate dimension of

reality, and

how he continues even now, so many years after his death, to feed us

grains of

sugar- and crumbs of bread-so that we may somehow make it through the

cold,

endless winter. •

(Translated, from the Hebrew,

by Stuart Schoffman.)

The New

Yorker June 8 & 15 2009

Bruno Schulz

Le printemps

Traduit du

polonais par Thérèse Douchy

D'où vient

ce mystérieux album de timbres qui semble avoir le pouvoir de

ressusciter les

grands personnages de l'Histoire ? Qui est Bianca, cette femme au

visage

d'ange? Quels liens a-t-elle avec ces revenants ? Où finit le passé et

où

commence le présent ?

Le

printemps, saison du retour à la vie, devient le théâtre d'événements

troublants, aux allures parfois fantastiques.

Écrivain

secret, Bruno Schulz nous

entraine dans son univers onirique et strange

transcendé par une langue poétique à la fois riche et exceptionnelle.

Cette

nouvelle est extraite du recueil Le

sanatorium au croquet-mort

(L'Imaginaire

n° 437).

Tuổi

thiên tài

Troisième

enfant d'un drapier Israélite, Bruno Schulz nait en1892

à Drohobycz. Sa ville natale, petite

bourgade de Galicie à l'est de l’Empire austo-hongrois, est rattachée à

la

Pologne à la suite des bouleversemenrs de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Trop

jeune pour s'engager lors du conflit, it apprend néanmoins la peur er

la

souffrance. Après des études d'architecture et de peinture à Vienne, it

revient

à Drohohycz enseigner le dessin; it ne quittera plus guère sa ville

qui

deviendra le décor de la plupart de ses textes. II commence à écrire

par

hasard, en correspondant avec des amis à qui it raconte sa famille, ses

concitoyens, tous les petits événements qui rythment son quoridien

solitaire.

Peu à peu, ces lettres deviennent des récits, et donnent naissance aux

recueils Les boutiques de cannelle en 1934 et Le sanatorium au croquet-mort en 1937.

Empreints de rêves, parfois de fantastique, ces textes puisent leur

inspiration

dans les souvenirs d'enfance et expriment une profonde angoisse tout en

décrivant

avec amertume le monde moderne, à la fois pathétique et grotesque. Bien

que ces

texts ne rencontrent pas de succès en librairie, ils lui permettent de

se faire

remarquer par l'intelligentsia et par les écrivains polonais qui

saluent son génie,

son originalité et son talent. En 1936, it traduit Le Procès de Franz

Kafka et

contribue ainsi à faire connaitre l’écrivain praguois dans son pays. Il

illustre de ses dessins la première édition de Ferdydurke

de son

contemporain Witold Gombrowicz ainsi que ses propres oeuvres. Enfermé

en 1941

dans le ghetto de Drohobycz lors de l’avancée allemande, il commence un

roman

qu'il n'achevera malheureusement pas: un SS l’abat d’une balle dans la

nuque

le 19 novembre 1942 et le manuscript disparait dans les ruines du

ghetto.

Malgré une oeuvre

littéraire restreinte, BrunoSchulz est considéré comme l’un des plus

grands écrivains

polonais du xze siècle et influence tous les domaines artistiques.

L'écrivain Isaac

B. Singer disait de lui «Parfois il écrivait comme Kafka, parfois

comme

Proust, et il a fini par atteindre des profondeurs auxquelles ni l'un

ni

l'autre n'avaient accédé.”

Đọc những còm

của mấy đấng độc giả, trong có nhà thơ ‘nhớn’, về một truyện ngắn của

HNT đăng

trên DM, Gấu nhận ra, chẳng đấng nào là ‘tri âm’ của nhà văn đã mệnh

một!

Chán thế!

Bèn post bài giới thiệu

‘thiên tài của tuổi thiên tài’, của ‘trưởng thành vào

tuổi thơ’,

Bruno Schulz, trong cuốn Le Printemps,

và lèm bèm thêm, như thế này:

Bạn có thể

coi đây là bài viết về HNT của Mít chúng ta, và, nhớ là, đừng so sánh

‘mức độ’ thiên

tài, giữa hai đấng tài hoa mệnh bạc!

Cũng đừng ngậm ngùi với cái chết

héo mòn của

ông, như cả một thế hệ văn chương Miền Nam cùng với ông, sau 1975, với

cái chết

vì một viên đạn bắn vào ót của Schulz. Bởi vì:

HNT

rất giống Schulz, [đọc Tuổi thiên tài],

ở đời thường, khoan nói chuyện

văn chương, nghệ thuật. Cả hai đều khốn khổ khốn nạn, sinh ra đời là đã

chỉ

muốn xin lỗi cuộc đời, xin lỗi, tớ tới nhầm chỗ, đúng ra tớ không nên

bò ra cõi

đời này!

*

V/v Bạn của HNT: Gấu biết hai ông, rất thân với HNT, khi sinh thời.

Một, là nhà phê bình văn học nổi tiếng của Miền Nam trước 1975, một bạn

văn, bạn

lính, mà còn là bạn mê bóng đá, bóng tròn, đá bóng… Lạ, là chẳng bao

giờ hai ông

này thỏ thẻ về cái chuyện được là bạn của thiên tài tuổi thơ cả!

Còn

một tay nữa, cũng rất thân với HNT, nhưng cũng ngại nói tên ra ở đây….

Cái cảm giác, 'xin lỗi tớ đến lộn chỗ', của HNT, là của Gấu, lần đầu

gặp HNT,

hình như tại cà phê Bà Lê Chân thì phải.

"Parfois

il écrivait comme Kafka, parfois comme Proust, et il a fini par

atteindre des

profondeurs auxquelles ni l'un ni l'autre n'avaient accédé.”

“Đôi khi

ông

ta viết như Kafka, đôi khi như Proust, và sau cùng ông đạt tới những

chiều sâu

mà cả hai ông kia, chẳng ai đạt tới”

|

|