|

|

Số

báo này có quá

nhiều bài tuyệt cú mèo. Bài về Giáo Đường,

của Faulkner, khui ra một chi tiết thật thú vị: Cuốn Pas

d'Orchidées pour Miss Blandish (1938) của J.H. Chase, đã từng

được Hoàng Hải Thuỷ phóng tác thành Trong

vòng tay du đãng, là từ Giáo Đuờng

bước thẳng qua. Cái từ tiểu thuyết đen, roman noir, của Tây không thể

nào dịch

qua tiếng Mẽo, vì sẽ bị lầm, "đen là da đen", nhưng có một từ thật là

bảnh thế nó, đó là "hard boiled", dur à cure, khó nấu cho sôi, cho

chín. Cha đẻ

của từ này, là Raymond Chandler, cũng một hoàng đế tiểu thuyết đen!

Bài viết về Chandler

của nữ hoàng trinh thám Mẽo, Patricia Highsmith cũng tuyệt. Rồi bài trả

lời

phỏng vấn của Simenon, trong đó, ông phán, số 1 thế kỷ 19 là Gogol, số

1 thế kỷ

20 là

Faulkner, và cho biết, cứ mỗi lần viết xong một cuốn tiểu thuyết là mất

mẹ nó hơn 5 kí lô, và gần một tháng ăn trả bữa mới bù lại được!

Bài trò chuyện với tân nữ hoàng trinh thám Tây Fred Vargas cũng tuyệt

luôn: "Tôi chơi trò thanh tẩy" ["Je joue le jeu de la catharsis"]. Viết

trinh thám mà là thanh tẩy!

Bài nào cũng muốn dịch cống hiến độc giả Tin Văn, trong khi bận lo dọn

Kít!

Chán thật!

Mệt thật!

*

Nhưng

mà , em mệt thật đấy!

Gấu vẫn

tự hào, rất rành về

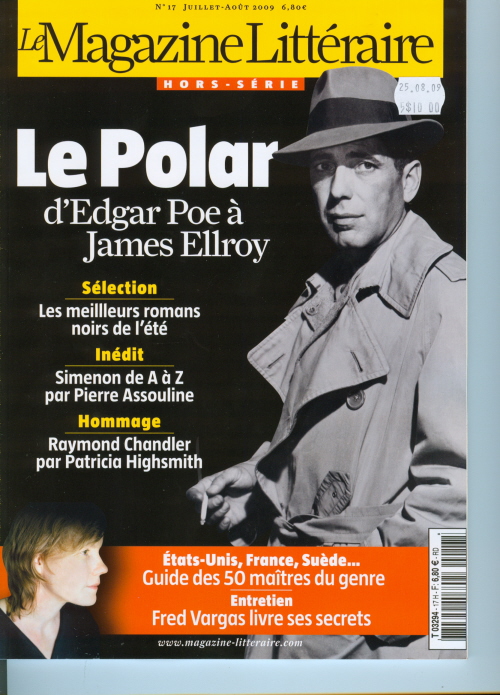

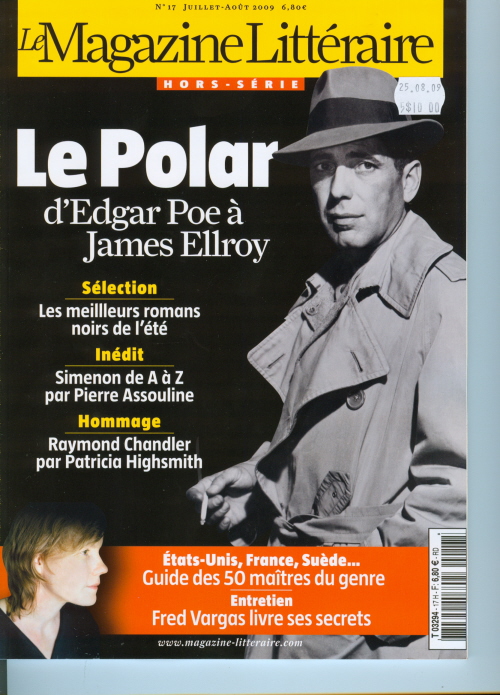

thầy, nhưng đọc bài viết về Faulkner, trong số báo Le Magazine

Littéraire, đặc biệt về Le Polar [Polar là

từ tiểu

thuyết trinh thám, roman policier, viết tắt], thì mới hiểu ra là, đây

mới là

người hiểu Faulkner,

do hiểu thời của Faulkner, nhờ vậy quy tụ được một số tác giả, tưởng

chừng chẳng

liên hệ gì tới ông. Thí dụ như Horace McCoy, tác giả cuốn On

achève bien les chevaux, chính là cuốn mà Gấu đã dịch cho me-xừ

Phạm Mạnh Hiên, những ngày sau 1975, với cái tít Khiêu Vũ

Với Tử Thần.

Bản dịch của Gấu đã gây ra một

trận phong ba nơi tòa soạn phía Nam của nhà xb Văn Học, thời Hoàng Lại

Giang,

khi đó PMH là một đệ tử dưới trướng của ông này.

Giai thoại này tuyệt lắm. Thư

thả kể hầu quí vị.

*

Cuốn Người ta làm thịt cả

ngựa, của Horace McCoy, là một cuốn sách đen, série noire, Gấu

đọc từ trước

1975, thời gian vừa đọc vừa học tiếng Tây, cùng với những tác giả như

Simenon,

J.H. Chase.. thời kỳ ra trường Bưu Điện

chừng hai năm, đã đổi qua bên VTD Quốc Tế, cầy thêm job cho UPI, đọc

cùng lúc

với ông Hưng, chuyên viên gửi hình VTD, radiophoto, của AP, ông Hưng

thì mê

những tác giả khác không giống Gấu, thí dụ Carter Brown.

Sau 1975, tay PMH nhờ Gấu

dịch theo nguyên tác tiếng Anh, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

Tay này làm cho

nhà xuất bản Văn Học, bộ phận phía Nam, và còn là một lái

sách. Gấu

biết anh ta, khi đến VH để lo biên tập cuốn Mặt Trời Vẫn Mọc, theo bản dịch

trước 1975 của Gấu, dưới sự giám sát của tay Nhật Tuấn, nhà văn Miền

Bắc, anh

ruột, hay em ruột của Nhật Tiến. Cái vụ xb lại cuốn này, là cũng nhờ

Nguyễn

Mai, khi đó làm thợ sửa mo rát cho VH.

Để có được bản dịch cuốn MTVM, Gấu phải

cầu cứu Jospeph Huỳnh Văn, có bà con làm ở Thư Viện Quốc Gia, nhờ mượn

về, đưa

cho nhà xb VH làm mẫu.

Joseph HV tới lúc đó mới đọc văn dịch của Gấu, gật gù,

mi bảnh thật, hơn cả thằng em tao, nó Tú Tài Tây, mà thua mi!

Đưa trước một mớ. Dịch xong,

anh ta đếch thèm in.

Thế rồi một bữa, Gấu thấy cuốn sách của mình nằm ngay

trước mắt mình, vì lúc đó, Gấu đang làm thằng bán báo, tại sạp nhà,

ngay trước

chúng cư 29 Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm Sài Gòn

*

On achève bien les chevaux

Titre original They Shoot

Horses, Don't They?

inspiré du roman de Horace

McCoy

On achève bien les chevaux

(They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? dans la version originale) est un film

américain réalisé par Sydney Pollack, sorti sur les écrans en 1969.

inspiré

d'un roman de Horace McCoy.

L’action se situe au début

des années 1930, en Californie. Au cœur de la grande dépression, on se

presse

pour participer à l’un des nombreux marathons de danse organisés à

travers le

pays pour gagner les primes importantes qui y sont mises en jeu. Robert

et

Gloria font partie de ces candidats...Au-delà de l'anecdote, c’est à

une

lecture de notre propre société qu’invite ce film, par opposition entre

l'enfer

que vivent les participants de ce marathon - privés de sommeil et de

temps de

réfléchir, et soumis à des épreuves cruelles (où mourra l'un d'entre

eux) - et

la beauté du paysage et du soleil levant entrevus de façon fugitive à

l'extérieur. Sydney Pollack indiqua avoir attaché une grande importance

au

personnage de l'animateur, « symbole de tout ce que l'Amérique avait de

pire et

de meilleur ». Mais on peut aussi y voir une réflexion sur l'absurdité

de la

condition humaine

Wikipedia

*

Cái cuốn truyện, sau chuyển

thể điện ảnh, Gấu đọc, trước 1975, và dịch, sau 1975, như tiên đoán cơn

suy

thoái của Mẽo, và của thế giới, thế mới quái dị, nếu bạn đọc những lời

giới

thiệu trên.

Tay PMH, không hiểu nghe ai

nói về cuốn sách, đưa Gấu bản tiếng Anh, Gấu đánh vật với nó, đến khi

đưa, anh

ta chê, vứt một xó, Đoàn Thạch Biền nhặt lên, bèn ơ rơ ka một phát, hay

như thế

này mà sao mày chê, đúng là... thi sĩ!

Ui chao, chẳng lẽ cái nhìn

tiên tri của anh "tiên tri" đến tận những ngày này?

Cái tít Khiêu Vũ với Thần

Chết quả là đắc địa!

Những đứa con của trí tưởng

Les classiques

William Faulkner

Polars

clandestins

Peut-on considérer certains

livres de Faulkner comme des romans noirs, à commencer par le fameux

Sanctuaire? L'écrivain était en tout cas friand de « crime publications

».

Par JEAN-BAPTISTE BARONIAN

Il

existe deux catégories de

roman noir: une première qui n'est qu'une métamorphose du récit de

détention,

une seconde, beaucoup plus originale, qui inaugure une véritable

révolution en

plaçant à l'avant-plan de l'intrigue un nouveau personnage: le coupable

lui-même. Et celui-ci, selon les cas, est gangster, assassin, tueur

fou,

proxénète, trafiquant, faussaire ou voleur. Dans cette perspective, les

premiers auteurs représentatifs du genre, aux États-Unis, ne sont pas

tant

Hammett ou Chandler

(leurs héros contiinuent d'être des limiers) que William Burnett,

Donald

Clarke, James Cain et Horace McCoy. On remarquera au surplus que les

livres qui

les ont fait largement connaître ont tous été publiés dans les années

de crise,

c'est-à-dire entre 1929 et 1935: Le Petit

César et Un dénommé Louis Beretti

en 1929, Le facteur sonne toujours deux fois

en 1934 et On achève bien les chevaux

en 1935.

À ces noms, il convient

d'ajouter celui, prestigieux, de William Faulkner. Chose curieuse, on

évite en France

de le

ranger au sein des auteurs du genre, sans doute parce que ce dernier

est mal

perçu ou parce qu'il est toujours de bon ton de dénigrer la littérature

policière,

sous prétexte qu'elle est le plus souvent mal écrite et qu'elle

s'adresse au plus grand nombre. Au surplus, les

spécialistes français eux-mêmes négligent le Faulkner « romancier noir

», comme

on en a une preuve en parcourant le numéro de la revue Europe,

paru en août-septembre 1984 et consacré au roman noir

américain: Faulkner n'y est pas étudié et c'est en vain qu'on

chercherait ici

une allusion relative à son œuvre. En revanche, de l'autre côté de

l'Atlantique, on ne manque jamais de souligner que Faulkner a, lui

aussi, écrit

des histoires criminelles. Ce qui explique pourquoi un article lui est

dévolu

dans l'ouvrage de base Twentieth-century crime and mysterywriters, dont

la

deuxième édition date de 1985 et où son nom figure, en bonne place

entre Howard

Fast et Kenneth Fearing.

Pour Hugh Holman, l'auteur de

l'article, cinq titres de Faulkner relèvent directement des « crime

publications

»: Sanctuaire, Lumière d'août,

Absalon, Absalon!, L'Intrus et Le Gambit du cavalier.

Il est certain que le

premier d'entre eux est le plus typique du roman noir. Faulkner y

travailla de

janvier à mai 1929, surtout dans l'intention de faire de l'argent et de

rencontrer le succès auprès du public. «J'ai songé, dira-t-il plus

tard, à ce

que je pouvais imaginer de plus horrrible et je l'ai mis sur le papier.

» Ce à

quoi il aura songé est le milieu de la pègre, telle qu'elle vivait dans

l'État

du Mississippi,

à la fin des années 1920, en s'adonnant à la fois au jeu, à la

prostitution et

à la contrebande d'alcool. On peut donc raisonnablement penser que

certains

personnages de Sanctuaire et certaines situations décrites ont un fond

de

vérité. Selon David Minter, un des biographes de Faulkner, l'étonnant

Popeye,

peut-être le plus sinistre héros faulknérien, aurait été inspiré par un

gangster célèbre de Memphis,

un dénommé Popeye Pumphrey. Quant à Miss Reba, elle ne serait que la

transposition d'une prostituée connue, à l'époque, de toute la ville.

Est-ce à

dire que le roman est le reflet précis d'un monde que Faulkner avait

sous les

yeux? Répondre à la question par l'affirmative reviendrait à banaaliser

le

livre et, plus encore, à déconsidérer la puissance créatrice de

l'auteur et son

extraordinaire génie de romancier. Ce qui est sûr, c'est que Sanctuaire

est, au

premier abord, un roman d'action dramatique et qu'il ne contient que

peu d'éléments

relevant de l'analyse. En cela, Faulkner a, d'évidence, atteint son

objectif:

raconter une histoire qui soit de nature à intéresser des lecteurs de

récits

d'aventures et de mystère. Lui-même, du reste, en aura toujours été

friand et

on sait que, dans sa propre bibliothèque, il conservait des livres

d'Agatha

Christie, de John Dickson Carr, de Dorothy Sayers, d'Ellery Queen et de

Rex

Stout.

Sanctuaire

inspirera d'ailleurs un fameux polar stricto

sensu, Pas d'orchidées pour Miss

Blandish, de James Hadley Chase (dont la première version date de

1938).

Les héros de Chase rappellent en effet nettement ceux conçus par

Faulkkner,

surtout Miss Blandish elle-même et Slim Grisson. Ainsi, si Popeye, dès

son plus

jeune âge, découpait des perruches en petits morceaux pour attiser son

plaisir,

Slim Grisson ne peut, lui, réellement exprimer l'amour étrange qu'il

nourrit

pour Miss Blandish que par des actes sadiques et violents, par exemple

lorsqu'il veut sublimer sa virilité devant elle en se servant d'un

couteau. Que

Chase se soit nourri du livre de Faulkner, cela ne semble faire aucun

doute.

L'adéquation thématique est patente. Il reste que dans Sanctuaire

l'action policière est des plus ténues, et que le ton

adopté par Chase évoque davantage celui inauguré par Dashiell Hammett

dans Le Faucon de Malte, paru en

1930, le premier véritable roman noir de l'histoire

de la littérature moderne, écrit selon une étonnante esthétique de

l'ellipse.

Il demeure surtout que la vision de Chase, pour efficace qu'elle soit,

ne

parvient jamais à l'intensité tragique, à la sombre et sensuelle

âpreté, à la

majesté bouleversante et hallucinante qui traverse Sanctuaire

d'un bout à l'autre.

Sanctuaire

n'est

en effet pas un roman d'action comme un autre, et certainement pas un

ouvrage

de série. Car ce qui y est dit est si effroyable, si cru, si brutal

qu'il

sacralise une véritable esthétique de la perversion, exprimée selon une

vision

douloureuse de la sexualité et du crime. Tous les personnages du livre

sont, de

fait, des corrompus, entièrement fascinés par la violence et la luxure,

totalement soumis à l'emprise du mal. Dans ces conditions, on comprend

pourrquoi André Malraux a parlé de Sanctuaire comme d'une

tragédie, en sachant fort

bien

ce que recouvrait le mot. D'où aussi ces phrases de Marc Saporta, dans

sa «

psychobiographie» de Faulkner (1) : « On trouve au cœur de Sanctuaire

l'un des

ressorts les plus révélateurs dont use la mythologie pour nous

renseigner sur

la condition humaine: l'homme ou la femme semble s'acharner avec

persévérance à

faire son propre malheur. » Compte tenu de ce qui précède, il

n'est donc pas

exagéré de prétendre que le livre constitue une parabole, à l'instar de

tout ce

que Faulkner a écrit, de sa jeunesse à sa consécration internationale,

et

jusqu'à la publication, en 1962, l'année même de sa mort, de son

dernier roman Les Larrrons où, il faut le souligner,

resurgit le personnage de Miss Reba. Autant dire que Faulkner, malgré

son souci

de sacrifier à la littérature de genre, dans le but de faire bouillir

la

marmite, n'a pu contenir ses hantises les plus profondes et a été

incapable

d'étouffer les pulsions qui le poussaient sans cesse vers la feuille

blanche. Et

c'est là ce qui devait arriver aussi à Georges Bernanos lorsque, pour

des

besoins alimenntaires il allait se mettre à écrire Un crime.

Au demeurant, après avoir lu le manuscrit de Sanctuaire en

1929, Hal Smith, l'éditeur

de Faulkner, ne cachera pas sa surprise. «Bon Dieu! lui dira-t-il dans

une

lettre, je ne peux pas publier ça! On nous mettrait en prison tous les

deux. »

De telle sorte que Sanctuaire ne

paraîtra, remanié, qu'en 1931, soit deux ans après Le

Petit César de Burnett et Un

nommé Louis Beretti de Clarke. Et il aura fallu attendre l'année

1981 pour

que soit éditée la version originale du roman. Après tout, est-ce si

étonnant

que Sanctuaire ait les accents d'une

parabole? D'un certain point de vue, le roman noir, le vrai, n'est

jamais

qu'une fable sur la transgression. Or, chez Faulkner, tout est

transgression.

Et c'est pourquoi il est impossible de lire son œuvre éblouissante sans

avoir

la tête en feu et sans avoir la certitude que ce sont bien le bruit et

la

fureur qui président aux destinées du monde.

(1) M. Saporta. Les Erres du faucon, une psychobiographie

de

William Faulkner, éd. Seghers, 1984,412 p., 26,68 €.

*

William Faulkner: The

Sanctuary of Evil

Mario Vargas Llosa

Faulkner suốt đời giữ cái

nhìn tiêu cực của ông, với Sanctuary, câu chuyện một cô gái bị một tên

liệt

dương phá huỷ trinh tiết bằng một cái bắp ngô, bởi vì, cả nửa thế kỷ,

sau những

dòng tự kiểm hồi sách mới ra lò, trong lần nói chuyện tại Đại học

Virginia,

[Vintage Books, New York, 1965], ông vẫn còn chê đứa con hư hỏng của

mình, coi

đây là một câu chuyện "yếu" và được viết bởi những tà ý [base

intentions].

Nhưng đây là một đại tác phẩm

của ông. Hai Lúa cứ liên tưởng tới Giáo Đuờng Của Cái Ác, ở một xứ sở

khác, ở

đó, có những tên già, liệt dương hay không liệt dương, lôi con nít vào

khách

sạn hãm hiếp, xong xuôi, đuổi ra, quẳng cho cô bé hình như là một trăm

đô thì

phải, thí dụ như một tay LQD nào đó.

Bởi vì, chỉ có thiên tài mới

có thể kể một câu chuyện như thế, với những sự kiện như thế, với những

nhân vật

như thế, bằng một cách kể mà người đọc, không chỉ chấp nhận, gật gù, kể

được,

được đấy, mà còn như bị quỉ sứ hớp hồn!

Như chính Faulkner đã từng

kể, ông viết Giáo Đường, bản viết đầu, trong ba tuần lễ, năm 1929, liền

sau Âm

thanh và Cuồng nộ. Ý tưởng về cuốn sách, như ông giải thích, trong lần

in thứ

nhì [1932], thứ tiểu thuyết ba xu, và ông viết, chỉ vì một mục đích duy

nhất,

là tiền, [trước nó, thì chỉ vì vui, for "pleasure"]. Phương pháp của

ông, là, "bịa ra một câu chuyện ghê rợn nhất mà tôi có thể tưởng tượng

ra

được", một điều gì một con người miệt vườn, vùng Mississipi, có thể coi

như là một chủ đề. Quá sốc, khi đọc, tay biên tập bảo ông, hắn sẽ chẳng

bao giờ

xuất bản một cuốn sách như thế, bởi vì, nếu xb, là cả hai thằng đều đi

tù.

Bản viết thứ nhì cũng chẳng

kém phần ghê rợn...

Được coi như, hiện đại hóa bi

kịch Hy Lạp, viết lại tiểu thuyết gothic, ám dụ thánh kinh, ẩn dụ chống

lại

công cuộc hiện đại hoá mang tính kỹ nghệ nền văn hóa Miền Nam nước Mẽo

vân vân

và vân vân. Khi Faulkner mang đứa con hư của mình trình làng văn Tây,

André

Malraux phán, đây đúng là, "đưa tiểu thuyết trinh thám vô trong bi kịch

Hy

Lạp", và khi Borges nói dỡn chơi, rằng những tiểu thuyết gia Bắc Mỹ đã

biến "sự tàn bạo thành đức hạnh", chắc chắn, ông ta có trong đầu lúc

đó, cuốn Giáo Đường của Faulkner.

Fiction does not reproduce

life; it denies it, putting in its place a conjuring trick that

pretends to

replace it. But, in a way that is difficult to establish, fiction also

completes life, adding to human experience something that men do not

meet in their

real lives, but only in those imaginary lives that they live

vicariously,

through fiction.

The irrational depths that are also part of

life are beginning to reveal their secrets and, thanks to men like

Freud, Jung

or Bataille, we are beginning to know the way (which is very difficult

to

detect) that they influence human behaviour...

Giả tưởng không

tái sản xuất cuộc đời, nó

chối từ cuộc đời, và, đặt ở đó, một trò ảo thuật, [một trò mà con mắt,

như

Sartre đã từng chê Sartoris của Faulkner], giả như là cuộc đời. Nhưng,

bằng một

cách nào đó, thật khó xác định, giả tưởng cũng hoàn tất cuộc đời, bằng

cách

thêm vào kinh nghiệm con người, một điều gì con người chưa từng gặp,

trong đời

thực của họ, và nhờ giả tưởng, mà họ được nếm mùi vị của nó.

Những vùng sâu

phi lý, ngoại lý, cũng là

một phần của cuộc đời, nhờ những người như Freud, Jung, hay Bataille

bắt đầu lộ

ra, và chúng ta bắt đầu hiểu, cung cách, đường hướng [thật khó tách

bạch hẳn ra

được], chúng ảnh hưởng lên cách ứng xử của con người.

William Faulkner: The

Sanctuary of Evil

According to his own

testimony, Faulkner wrote the first version of Sanctuary

in three weeks in 1929, immediately after

The Sound and the

Fury. The idea of the book, he explained in the second edition of the

novel

(1932), had always seemed to him 'cheap' because he had conceived it

with the

sole intention of making money (up to then, he had

only written for 'pleasure'). His method was

'to invent the most horrific tale that I could imagine', something that

someone

from the Mississippi

could take as a topical theme. Aghast at the text, his editor told him

that he

would never publish such a book since, if he did so, both of them would

go to

prison.

Then, while he was working in

a power plant, Faulkner wrote As I Lay Dying. When this book came out,

he

received the proofs of Sanctuary which the editor had finally decided

to

publish. On rereading his work, Faulkner decided that the novel was

indeed

unpresentable as it stood and made many corrections and deletions, to

such an

extent that the version which appeared in 1931 differed considerably

from the

original. (A comparison of both texts can be found in Gerald Langford,

Faulkner's Revision of Sanctuary, University of Texas Press, 1972.)

The second version is no less

'horrific' than

the first: the main horrifying events of the story occur in both

versions, with

the exception of the discreetly incestuous feelings between Horace and

Narcissa

Benbow and Horace and his stepdaughter Little Belle, which are much

more

explicit in the first version. The main difference is that the centre

of the

first version was Horace Benbow, while in the new one, Popeye and Temple Drake

have grown and have relegated the honest and weak lawyer to a minor

role. With

regard to structure, the original version was much clearer, despite the

temporal complexities, since Horace was the perspective from which

nearly all

the story was narrated, while in the definitive version the tale

continually

changes point of view, from chapter to chapter, and sometimes even

within a

single paragraph.

Faulkner maintained his

negative opinion of

Sanctuary throughout his life. A half century after that self-critical

prologue, in his Conversations at the University of Virginia

(Vintage Books, New York, 1965), he once again called his story - at

least in

its first version - 'weak' and written with base intentions.

In fact, Sanctuary is one of

his masterpieces

and deserves to be considered, after Light in August and Absalom,

Absalom,

among the best novels of the Yoknapatawpha saga. What is certain is

that with

its harrowing coarseness, its dizzying depiction of cruelty and

madness, and

its gloomy pessimism, it is scarcely tolerable. Precisely: only a

genius could

have told a story with such events and characters in a way that would

be not

only acceptable but even bewitching for the reader. This almost

absurdly

ferocious story is remarkable for the extraordinary mastery with which

it is

told, for its unnerving parable on the nature of evil, and for those

symbolic

and metaphysical echoes which have so excited the interpretative

fantasy of the

critics. For this is, without doubt, the novel of Faulkner that has

generated

the most diverse and baroque readings: it has been seen as the

modernization of

Greek tragedy, a rewriting of the Gothic novel, a biblical allegory, a

metaphor

against the industrial modernization of the culture of the South of the

United

States etc. When he introduced the book to the French public in 1933,

André

Malraux said that it represented 'the insertion of the detective novel

into

Greek tragedy', and Borges was surely thinking of this novel when he

launched

his famous boutade that North American novelists had turned 'brutality

into a

literary virtue'. Under the weight of so much attributed philosophical

and

moral symbolism, the story of Sanctuary tends to become diluted and

disappear.

And, in truth, every novel is important for what it tells, not for what

it

suggests.

What is this story? In a

couple of sentences,

it is the sinister adventure of Temple Drake, a pretty, scatterbrained

and

wealthy girl of seventeen, the daughter of a judge, who is deflowered

with an

ear of corn by an impotent and psychopathic gangster - who is also a

murderer.

He then shuts her away in a brothel in Memphis where he

forces

her to make love in front of him with a small-time hoodlum whom he has

brought

along and whom he later kills. Woven into this story is another,

somewhat less

horrific: Lee Goodwin, a murderer, an alcohol distiller and bootlegger

who is

tried for the death of a mental defective, Tommy (who was killed by

Popeye),

condemned and burned alive despite the efforts of Horace Benbow, a

well-intentioned lawyer, to save him. Benbow cannot make good triumph.

These horrors are a mere

sampling of the many

that appear in the book, in which the reader encounters a strangling, a

lynching, various murders, a deliberate fire and a whole raft of moral

and

social degradation. In the first version, furthermore, the character

endowed

with a moral conscience, Horace, was caught in the grip of a double

incestuous

passion. In the final version this has been softened to the extent that

it

remains as scarcely a murky trace in the emotional life of the lawyer.

In every novel it is the form

- the style in

which it is written and the order in which it is told - which

determines the

richness or poverty, the depth or triviality, of the story. But in

novelists

like Faulkner, the form is something so visible, so present in the

narration

that it appears at times to be a protagonist, and acts like another

flesh and

blood character, or else it appears as a fact, like the passions,

crimes or

upheavals; of its story.

The effectiveness of

Sanctuary's form stems

above all from what the narrator hides from the reader, putting the

facts in a

different place in the chronology, or leaving them out altogether. The

yawning

gap in the novel - the barbarous deflowering of Temple - is an ominous silence,an

expressive

silence. Nothing is described, but from that unexpressed savagery a

poisonous

atmosphere seeps out and spreads to contaminate Memphis and other

places in the

novel, turning them into a land of evil, regions of ruin and horror,

beyond all

hope. There are many other hidden pieces of information, some of which

are

revealed retrospectively, after the effects that they cause - like the

murder

of Tommy or Red or the impotence of Popeye - and others which remain in

the

shadows, although we do learn something about them, enough to keep us

intrigued

and for us to surmise that in this darkness something murky and

criminal is

lurking, like the mysterious journeys and shady affairs of Clarence

Snopes and

the adventures of Belle, the wife of Horace.

But this manipulation

of the facts of the

story, which are withheld momentarily or completely from the reader, is

more

cunning than these examples might indicate. It occurs at every stage,

sometimes

in every sentence. The narrator never tells us everything and often

throws us

off the scent: he reveals what a person does, but not what he thinks

(Popeye's

private life, for example, is never revealed), or vice versa, with no

prior

warning, he depicts actions and thoughts of unknown people, whose

identity he

reveals later, in a surprising way, like a magician who suddenly makes

the

vanished handkerchief reappear. In this way, the story lights up and

fades;

certain scenes dazzle us with their illumination while others, almost

invisible

in the shadows, can only be glimpsed.

The pace of the narrative

time is also

capricious and variable: it speeds up and goes at the pace of the

characters'

dialogues, which the narrator recounts almost without commentary - as

for

example in the trial. In Chapter 13, the crater chapter, time is filmed

in slow

motion, almost stops and the movements of the characters seem like the

rhythmic

development of a Chinese shadow theatre. All the scenes of Temple Drake

in the house of the old Frenchman are theatrical, they move at a

ceremonial

pace which turns actions into rites. In this tale, with some

exceptions, the

scenes are juxtaposed rather than dissolving into each other.

All this is extremely

artificial, but it is

not arbitrary. Or rather, it does not seem arbitrary: it emerges as a

necessary

and authentic reality. The world, these creatures, these dialogues,

these

silences could not be otherwise. When a novelist succeeds in

transmitting to

the reader that compelling, inexorable sensation that what is being

narrated in

the novel could only happen in that way, be told in that way, then he

has

triumphed completely.

Many of the almost infinite

number of

interpretations of Sanctuary stem from the unconscious desire of

critics to

come up with moral alibis which allow them to redeem a world which is

described

in the novel as so irrevocably negative. Here once more we come up

against that

perennial view - which, it seems, literature will never be able to

shake off —

that poems or fiction should have some kind of edifying function in

order to be

acceptable to society.

The humanity that appears in

this story is

almost without exception execrable or, at the very least, wretched.

Horace

Benbow has some altruism, which makes him try to save Goodwin and help

Ruby,

but this is offset by his weakness and cowardice which condemn him to

defeat

when he tries to face up to injustice. Ruby also shows some spark of

feeling

and sympathy - she does at least try to

help Temple

-

but this does not have any useful outcome because she has been

inhibited by all

the blows and setbacks and is now too cowed by suffering for her

generous

impulses to be effective. Even the main victim, Temple, causes as much repugnance as

sympathy

in us because she is as vacuous and stupid - and, potentially as prone

to evil

- as her tormentors. The characters who do not kill, bootleg, rape and

traffic

— like the pious Baptist ladies who have Ruby thrown out of the hotel,

or

Narcissa Benbow - are hypocritical and smug, consumed by prejudice and

racism.

Only the idiots like Tommy seem less gifted than the rest of their

fellow men

in this world when it comes to causing harm to others.

In this fictional

reality, human evil is

shown, above all, in and through sex. As in the fiercest Puritans, an

apocalyptic vision of sexual life permeates all Faulkner's work, but in

no

other novel of the Yoknapatawpha saga is it felt more forcibly. Sex

does not

enrich the characters or make them happy, it does not aid communication

or

cement solidarity, nor does it inspire or enhance existence. It is

almost

always an experience that animalizes, degrades and often destroys the

characters, as is shown in the upheaval caused by Temple's presence in the Old

Frenchman's

house.

The arrival of the

blonde, pale girl, with

her long legs and delicate body, puts the four thugs - Popeye, Van,

Tommy and

Lee - into a state of excitement and belligerence, like four mastiffs

with a

bitch on heat. Whatever traces of dignity and decency that might still

survive

within them vanish when faced with this adolescent who, despite her

fear and

without really being conscious of what she is doing, provokes them.

Purely

instinctive and animal feelings prevail over all other feelings such as

rationality and even the instinct for survival. In order to placate

this

instinct, they are prepared to rape and to kill each other. Once she is

sullied

and degraded by Popeye, Temple

will adopt this condition and, for her as well, sex will from then on

be a

transgression of the norm, violence.

Is this animated

nastiness really humanity?

Are we like that? No. This is the humanity that Faulkner has invented

with such

powers of persuasion that he makes us believe, at least for the

duration of the

absorbing reading of the novel, that it is not a fiction, but life

itself. In

fact life is never what it is in fiction. It is sometimes better,

sometimes

worse, but always more nuanced, diverse and predictable than even the

most

successful literary fantasies can suggest. Of course, real life is

never as

perfect, rounded, coherent and intelligible as its literary

representations. In

these representations, something has been added and cut, in accordance

with the

'demons' - those obsessions and deep pulsations that are at the service

of

intelligence and reason, but are not necessarily controlled or

understood by

these faculties - of the person who invents them and bestows on them

that

illusory life that words can give.

Fiction does not reproduce

life; it denies it, putting in its place a conjuring

trick that pretends to replace it. But, in

a way that is

difficult to establish, fiction also completes life, adding to human

experience

something that men do not meet in their real lives, but only in those

imaginary

lives that they live vicariously, through fiction.

The irrational depths that

are also part of

life are beginning to reveal their secrets and, thanks to men like

Freud, Jung

or Bataille, we are beginning to know the way (which is very difficult

to

detect) that they influence human behaviour. Before psychologists and

psychoanalysts existed, even before sorcerers and magicians took on the

role,

fiction helped men (without their knowing it) to coexist and to come to

terms

wfth certain phantoms that welled out of their innermost selves,

complicating

their lives, filling them with impossible and destructive appetites.

Fiction

helped people not to free themselves from these phantoms, which would

be quite

difficult and perhaps counterproductive, but to live with them, to

establish a

modus vivendi between the angels that the community would like its

members

exclusively to be, and the demons that these members must also be, no

matter

how developed the culture or how powerful the religion of the society

in which

they are born. Fiction is also a form of purgation. What in real life

is, or

must be, repressed in accordance with the existing morality - often

simply to

ensure the survival of life - finds in fiction a refuge, a right to

exist, a

freedom to operate even in the most terrifying and horrific way.

In some way, what happened to

Temple Drake in

Yoknapatawpha County according to the tortuous imagination of the most

persuasive creator of fiction in our time, saves the beautiful

schoolgirls of

flesh and blood from being stained by that need for excess that makes

up part

of our nature and saves us from being burned or hanged for fulfilling

that

need.

London, December 1987

Mario Vargas Llosa

Những mắc mớ, liên hệ, giữa những tác giả tưởng chẳng liên hệ với nhau,

như J.H. Chase, Faulkner, McCoy, tất cả đều quy về một thằng Mít, là

Gấu, cùng chỉ ra cơn suy thoái về kinh tế trên toàn thế giới, và về đạo

đức riêng ở xứ Mít, liệu tất cả chỉ để nói ra điều này: Trong những

ngày nằm nhà thương Grall, BHD ghé thăm, trên đường đi, ghé tiệm sách ở

đường Lê Lợi, mua cho Gấu cuốn của Chase, Un beau matin d'été, và khi đưa cho

Gấu, hỏi đọc chưa, Gấu ngu quá, nói đọc rồi, và em buồn rầu nói, em

cũng nghi như vậy, khi mua!

Ui chao, số mệnh chẳng lẽ chi ly, châu đáo đến như thế, đối với thằng

cha Gấu?

|

|