|

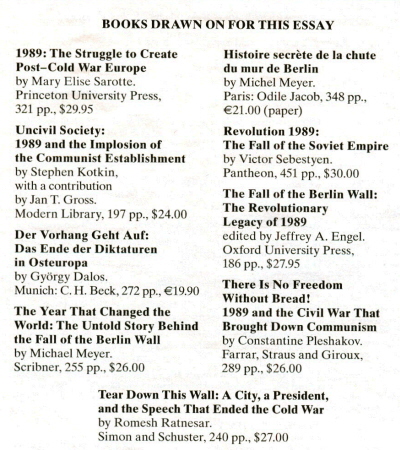

Notes

|

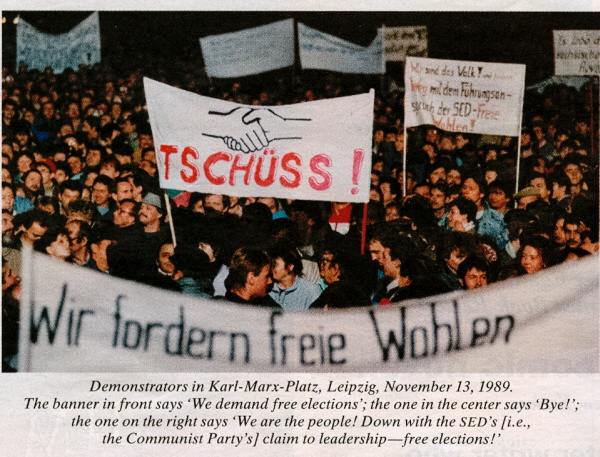

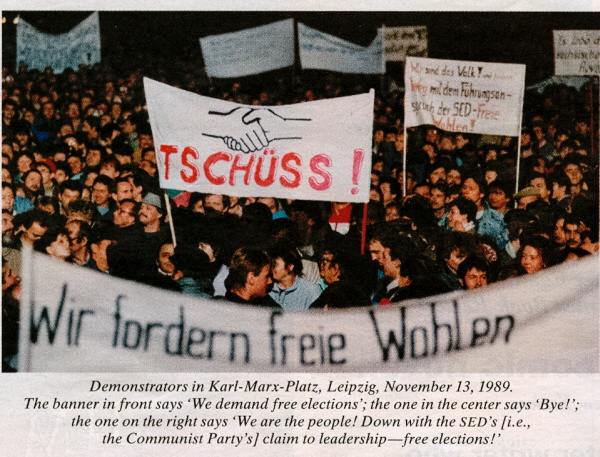

Biểu

tình chống VC Đông Đức. “Băng

rốn” trước mặt: “Chúng em” đòi bầu cử tự do.

Cái ở giữa: Bye, bye VC DD!

Cái bên

phải: Chúng em là nhân dân. Đảng nãnh đạo VCDD về vườn đi - Bầu cử tự

do.

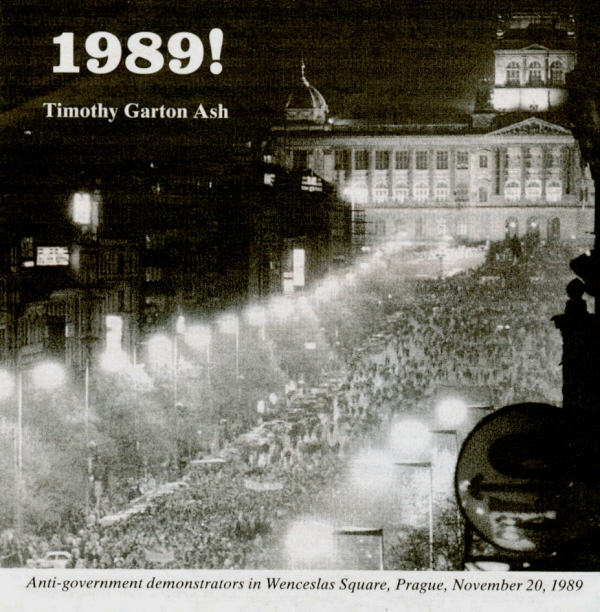

NYRB

Nov 5, 2009

Timothy Garton Ash:

1989 -

The Unwritten

History

1989 - Lịch sử không được

viết

ra

Velvet Revolution: The Prospects

Ash

viết:

Tôi trải qua nhiều giờ đứng

giữa đám đông ở Varsaw, Budapest, Berlin và Prague.

Cách ứng xử của họ thì vừa hứng khởi, vừa kỳ bí, inspiring and

mysterious. Điều

gì đẩy những cá nhân đàn ông đàn bà này ra đường phố, nhất là những

ngày đầu,

khi chẳng có chi đảm bảo an toàn? Điều gì khiến họ tụ lại thành những

đám đông?

Ai là người đầu tiên ở Prague,

lấy chùm chìa khoá ra khỏi túi và lắc lắc, khiến 300 ngàn người làm

theo, làm

thành điệu reo của những chiếc phong

linh?

Anatoly Chernyaev, tùy viên

của Gorbachev, ghi nhật ký ngày 10 Tháng 11, về sự sụp đổ Bức Tường Bá

Linh:

Đây là điều Gorbachev đã làm. Ông ta ngửi ra bước đi của lịch sử và

giúp nó

kiếm ra một lối đi tự nhiên. Thật là xấu hổ nhục nhã cho một con dân

người

Anh, khi bà thủ tướng sắt của họ, Margaret Thatcher có vẻ như đã phản

bội những

lời hứa công khai của bà với nước Đức: “Chúng tôi không muốn sự thống

nhất của nó”.

Bài viết của Ash là một trong ba viết; hai bài sau nhìn về thời kỳ

hậu-1989, và những viễn tượng của cuộc 'cách mạng nhung'.

Những cuộc cách

mạng 1989

Berlin

Wall

November 9th

by George Packer

Germany observes no official holiday on November

9th, the day

when, twenty years ago, crowds of stunned, delirious East Germans

breached the

Berlin Wall. This is because November 9th is also the date on which

Kaiser

Wilhelm abdicated, in 1918, two days before Germany’s

defeat in the First World

War. On November 9, 1923, Hitler attempted to overthrow the Weimar Republic,

in the Munich Beer Hall Putsch. In 1938, November 9th was the Night of

Broken

Glass, when Nazi gangs attacked Jews and their property across Germany and Austria,

foreshadowing the genocide

to come. The German calendar is appropriately inconvenient: nothing

good is

conserved without the active remembrance of something bad. The British

writer

Timothy Garton Ash has called 1989 the best year in European history.

It

delivered the Continent from its worst century—the new democratic

European

unity that began in 1989 was built on fifty million graves.

The

chain reaction of

nonviolent civic movements in Poland,

Hungary,

East Germany,

and Czechoslovakia

seemed like a

miracle at the time, and it still does. Anyone who grew up knowing

nothing but

the Cold War could scarcely imagine that the world wasn’t eternally

locked in

permafrost. No Hegelian teleology predetermined that Communism would be

left on

the ash heap of history. In 1989, Francis Fukuyama published his essay

“The End

of History?,” in which he predicted “the universalization of Western

liberal

democracy as the final form of human government.” This proved far too

optimistic for the post-Cold War world, and even in Central Europe, where liberal democracy did

emerge, the dramatic events

that brought it about were messier and chancier than the dreams of

neo-conservative philosophers.

The wall came down not

because Ronald Reagan stood up and demanded it but because on the

evening of

November 9th, at a televised press conference in East

Berlin, a Party hack named Günter Schabowski flubbed a

question

about the regime’s new, liberalized travel regulations. Asked when they

took

effect, Schabowski shrugged, scratched his head, checked some papers,

and said,

“Immediately,” sending thousands of East Berliners to the wall in a

human tide

that the German Democratic Republic could not control. Soldiers and

Stasi

agents didn’t shoot into the crowd, but things could easily have gone

otherwise.

The revolutions of 1989 were

made possible by a multiplicity of conditions: the courage of East Bloc

dissidents and the hundreds of thousands of fellow-citizens who finally

joined

them; American support for the dissident movements and containment of

the

Soviet Union; the disastrous economies of the Communist countries; the

loss of

confidence among ruling-party élites; the crucial forbearance of

Mikhail

Gorbachev. For Europe’s Communist regimes to disappear so suddenly and

bloodlessly (Romania

was a different story), everything had to fall into place, above and

below,

within and without. Such circumstances are improbably rare, and they

can’t be

mechanically replicated by the laws of history or by divine design or

by

universal human aspiration. A false lesson drawn from 1989 involves a

kind of

shallow eschatology of totalitarianism: this is how it always

happens—the

people rise up, the regime withers and dies, peace and democracy reign.

The

chaos that followed the overthrow of Saddam Hussein was in part a

consequence

of this thinking. In planning the postwar period in Iraq,

George W. Bush and some of his advisers had 1989 in mind—“like Eastern Europe with Arabs,” as one official put

it.

The last, briefest, and most

thrilling of that year’s peaceful uprisings, the Velvet Revolution,

took place

in Czechoslovakia.

Over the next two decades, it produced a series of successors and

imitators in Serbia,

Ukraine,

and Georgia.

While they all improved the politics of their respective countries,

none of them

had a Václav Havel, and none of them created a stable liberal

democracy.

Whenever things fail to turn out as they did in Central

Europe, people tend to react as if history had

unaccountably

malfunctioned. But if 1989 were the rule and not the exception, then

Burmese,

Chinese, and Zimbabwean dissidents—who have sacrificed far more than

their

European counterparts (in China,

1989 meant Tiananmen Square)—would be

in power

by now.

Perhaps the closest

contemporary analogy to the fall of Communism is the democratic

movement that

is challenging the Islamic Republic of Iran. It has deep social and

intellectual roots, a growing mass following, and an enemy state with a

hollowed-out ideology. But, unlike the East German soldiers and the

Stasi

agents, the Revolutionary Guards and the Basij militia are ready to

kill.

Behind President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei,

there is

no restraining figure like Gorbachev. Iranians will have to find their

own way

to the fulfillment of their democratic desires. And yet the fact that

the

nearest counterparts to the thinkers and activists of 1989 are to be

found in a

non-Western, Muslim country exposes another false lesson of that year:

that

such things are for Westerners only, that “they” don’t want what “we”

want.

A recent Pew poll shows that

Germans, Czechs, and Poles remain relatively enthusiastic about

democracy and

capitalism; Hungarians, Bulgarians, and Lithuanians less so. Former

East

Germans’ hopes of achieving the living standards of their Western

countrymen

have not been fulfilled, and the inevitable disappointments have muted

anniversary celebrations. Last month in Dresden,

a retired schoolteacher acknowledged the pining of some East Germans

for their

simpler, cozier former lives under state socialism. There’s even a

neologism

for it: Ostalgie. But, the teacher

said, “What matters is that I can talk with an American journalist

without

going to jail, that I can travel without filling out forms, that I can

read

what I want to read, that I’m not told what TV station I can watch and

not

watch, that at school I don’t have to say something that I don’t say in

private

at home. This is what is decisive to me today.”

Twenty years after the

revolutions of 1989, Europe’s bitter

half

century of armed division is the object of profitable kitsch. At

Checkpoint

Charlie, in central Berlin,

where an East German guard opened the gate at 11:17 P.M. that November

9th, you

can now pay a euro to pose with hucksters wearing Soviet, British,

French, and

American uniforms. Neighborhoods that used to be separated by the wall

have

become hotbeds of the art scene, the gay scene, and the club scene.

Meanwhile,

Germans widely regarded the recent election campaign, in which

fundamental

issues were avoided, as a snooze. Berlin

will

never again be the hair-trigger focus of global ideological conflict,

and Europe’s place at the center of

modern history is over.

This proves not the failure of 1989 but, rather, its astounding

success. No one

is prepared to die for European unity, and no one will have to. ♦

Wall Stories

No

worthy successor, yet,

to Solzhenitsyn

Chưa

có đệ tử xứng đáng để truyền y bát!

Missing in all this is a

powerful voice from the countries concerned. Writers such as

Solzhenitsyn,

Czeslaw Milosz, a Polish poet, and Czech novelists such as Milan

Kundera, Ivan

Klima and Josef Skvorecky helped the world understand life under

communism. But

no writer from the region, in fact or fiction, has produced a matching

account

of the collapse of the Iron Curtain and its aftermath. The way in which

the

countries of central Europe, the

Baltics and

the Balkans emerged from communist captivity, made peace (mostly) with

their

history, and rebuilt the economic, legal, moral and psychological order

destroyed five decades previously is a gripping story. It has yet to be

fully

told.

Thiếu, trong tất cả ở đây, là một tiếng nói mạnh mẽ từ những xứ sở được

quan

tâm. Những nhà văn như Solzhenitsyn, Czeslaw Milosz, một thi sĩ Ba Lan,

và những

tiểu thuyết gia

Czech như

Milan Kundera, Ivan Klima, và Josef Skvorecky giúp

thế giới

hiểu cuộc sống dưới chế độ Cộng Sản. Nhưng chưa một nhà văn nào trong

vùng, bằng

sự kiện hay bằng giả tưởng, tạo ra được một tác phẩm xứng hợp, ngang

hàng với

những tầm vóc nói trên, để kể cho chúng ta nghe, về cái sự sụp đổ của

Bức Màn

Sắt, và những gì tiếp theo sau. Con đường mà qua đó, những xứ sở vùng

Trung Âu,

vùng Baltics và những con người Balkans vượt ra khỏi sự giam cầm của

chủ nghĩa

Cộng Sản, làm hòa [hầu hết] với lịch sử của chúng, và tái tạo dựng trật

tự kinh

tế, hợp pháp, đạo đức, tâm lý, bị phá huỷ trong năm thập niên trước đó,

thì quả

là một câu chuyện kỳ tuyệt, câu chuyện đó chưa được kể ra một

cách đầy

đủ.

Ui chao bao giờ thì Mít có cái sự sụp đổ Bức Màn Tre?

[Mặc dù đếch còn một cây tre nào!]

Nói chi chuyện kể về nó?

|

|