TOMAS TRANSTROMER: A TRIBUTE

ROBERT HASS

TOMAS TRANSTROMER published

his first book of poems-the stunning I7 dikter-when he was

twenty-three years old. Eight volumes have followed, each rather austere

and beautifully made. The poems were, from the beginning, thick with the

feel of life lived in a particular place: the dark, overpowering Swedish

winters, the long thaws and brief paradisal summers in the Stockholm archipelago.

But they were also piercing inward poems, full of strange and intense accuracies

of perception. The most famous lines-

Awakening is a parachute jump

from the dream.

or

December. Sweden is a hauled-up,

unrigged ship

-stay with one a long time.

And there are whole passages

equally indelible:

Daybreak slams and slams in

the sea's grey stone gateway, and the sun flashes

close to the world. Half-choked

summer gods

fumble in sea-mist.

And this:

The black-backed gull, the sun-skipper,

steers his course.

Under him is wide water.

The world still sleeps like

a

many-coloured stone in the water.

Undeciphered days. Days-

like Aztec hieroglyphs!

Hieroglyph is- the right word. The brilliance

of the metaphors, and their originality, was what most attracted attention

of other poets and made Transtromer the most widely translated European poet

of the post-war generation. His work has been translated into fifty languages,

and as if each dialect required its own version, into English by English,

Irish, Scottish, and American poets. This is remarkable at least in part because

his work is not easy or immediately comforting. It was admired by poets first,

and that is the work in translation tells us.

His brilliance is very difficult to separate from the terseness and

almost classical restraint of a style that makes almost all other poets seem

garrulous, sociable, eager-even in their most rebellious attitudes-to please.

Transtromer's metaphors have a way of suggesting an uncannily alert imagination

turned to an undeciphered, but not entirely undecipherable, world. Its meanings

often come in hints, glimpses along the way, sometimes brutal and ancient,

sometimes unnervingly fresh. Almost always this world is as peculiar, bald,

and hermetic as the opening of a hand when we cannot say whose it is or what

purpose it intends. And almost in the poems, the everyday world, the one

organized he purposes of power, commerce, pleasure, and transportation, is

not the one we need to read. This way of seeing gives one the feeling, reading

him, that one ought to wake up from whatever one's previous idea of being

awake was, and it has made him one of the most urgent imaginations of our

time.

The later poems often occur in the moments between sleeping and waking,

between work and home, as a commuter he outskirts of cities, as a tourist

at the edge of cultures. It wasn’t without profit that Transtromer the poet

practised his profession as a psychologist in small cities outside Stockholm,

working as a psychotherapist and counselor in an institution for juvenile

offenders and then as a psychologist for a labor organization. This immersion,

or submersion, in the working world may be what gives his poems their intense

sense of what it is like for consciousness to try to locate itself around

the edges of the meanings - social, political, existential- it finds itself

among. That must be why so many of the poems take place along the blurred

seams of twentieth-century life, when the imagination has come unhinged a

little and ceases to know what it thinks it knows about itself. These poems,

more than any others I can think of, convey a sense what it is like to be

a private citizen in the second half of the twentieth century. Anywhere this

private citizenship exists-among the people who read and write books, for

example-the phrase conveys the idea of a certain freedom, a certain level

of comfort, and also some unease and isolation.

And this is another powerful feature of his art. It praises art, but

it never claims any special privilege from the situation of the artist. Maybe

it is in this way that Transtromer's break with modernism is most complete.

Other poets of his time and of his stature-one thinks of Zbigniew Herbert,

Seamus Heaney, Joseph Brodsky- have faced the public world and the public

horrors of their time with an art in their hands that served as both a hermeneutic

of suspicion and an honorable tradition of dissent, but Transtromer's poems

don't seem to lay claim to that tradition. Art, especially the art of music,

comes into his poems as other hieroglyphs, hopeful scents picked up from

the world's unpromising winds. One of the most powerful of these images comes

from his long poem Baltics, when he stumbles on a carved

baptismal font in an old church:

In the half-dark corner of Gotland

church,

in the mildewed daylight

stands a sandstone baptismal

font-12th century-

the stonecutter's name

still there, shining

like a row of teeth in a mass

grave:

HEGWALDR

the name still there. And his

scenes

here and on the sides of other

vessels crowded with

people, figures on their

way out of the stone.

The eyes' kernel of good and

evil bursting there.

Herod at the table: the roasted

cock flying up and

crowing, "Christus natus est"-

the servant executed-

close by the child born, under

clumps of faces as worthy

and helpless as young monkeys.

And the fleeing steps of the

pious

drumming over the dragon scales

of sewer mouths.

(The scenes stronger in memory

than when you stand

in front of them,

strongest when the font spins

like a slow, rumbling

carousel in the memory.)

Nowhere the lee-side. Everywhere

risk.

As it was. As it is.

Only inside there is peace,

in the water of the vessel

that no one sees,

but on the outer walls the struggle

rages.

And peace can come drop by drop,

perhaps at night

when we don't know anything,

or as when we're taped to a

drip in a hospital ward.

Reading this, one understands

that part of Transtromer's power is that, all along, he has been doing the

work of a religious temperament in a secular and dangerous age and why he

is, as the poet and critic Goran Printz- Pahlson has written, "one of the

central and most original poets of our time.”

Tomas suffered a stroke in I990 that left him paralyzed on his right

side and that affected his wife, Monica, is a nurse. I am told that, while

he was recovering, she drove to Stockholm, found a music store bought all

the piano literature for one hand she could locate, drove home, gave it to

Tomas, and told him to get to work.

It must have been an effective therapy. Tomas was a accomplished pianist,

and his publisher Bonniers has recently issued a CD that combines recordings

of his poems recordings of his work at the piano. The piano performances,

like his late works-the remarkable "Sad Gondola," and the haiku, a few syllables

like scratches in snow that make up most of The Great Enigma-feel

like metaphors for his art. One hand finding its way, note by note, in a

darkness it has made luminous.

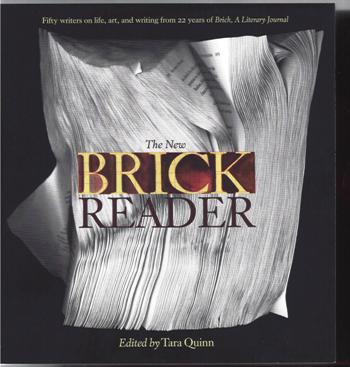

The New Brick Reader