|

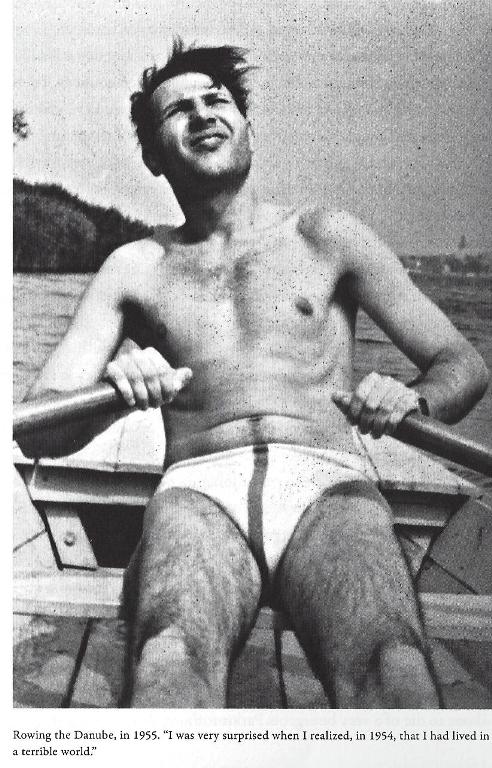

Đạp thuyền trên hồ Xuân Hương,

Đà Lạt, 1955, Gấu thực sự ngạc

nhiên, mình đang sống trong một thế giới khủng khiếp. INTERVIEWER Trong Hồ Sơ K. ông phán, chỗ của tớ không phải ở trong lịch sử, mà ở bàn viết. Kertesz: Tớ đếch viết ở bàn

viết. Nhưng thôi, bỏ ba chuyện lẻ tẻ đi vô đời tư,

nhảm lắm! Imre

Kertész, The Art of Fiction No. 220 Interviewed

by Luisa Zielinski INTERVIEWER In your

Nobel Lecture you said, “The nausea and depression to which I awoke

each

morning led me at once into the world I intended to describe.” Did

writing

subdue this condition? IMRE KERTÉSZ I was

suspended in a world that was forever foreign to me, one I had to

reenter each

day with no hope of relief. That was true of Stalinist Hungary, but

even more

so under National Socialism. The latter inspired that feeling even more

intensely. In Stalinism, you simply had to keep going, if you could.

The Nazi

regime, on the other hand, was a mechanism that worked with such brutal

speed

that “going on” meant bare survival. The Nazi system swallowed

everything. It

was a machine working so efficiently that most people did not even have

the

chance to understand the events they lived through. To me, there

were three phases, in a literary sense. The first phase is the one just

before

the Holocaust. Times were tough, but you could get through somehow. The

second

phase, described by writers like Primo Levi, takes place in medias res,

as

though voiced from the inside, with all the astonishment and dismay of

witnessing

such events. These writers described what happened as something that

would

drive any man to madness—at least any man who continued to cling to old

values.

And what happened was beyond the witnesses’ capacity for coping. They

tried to

resist it as much as they could, but it left a mark on the rest of

their lives.

The third phase concerns literary works that came into existence after

National

Socialism and which examine the loss of old values. Writers such as

Jean Améry

or Tadeusz Borowski conceived their works for people who were already

familiar

with history and were aware that old values had lost their meaning.

What was at

stake was the creation of new values from such immense suffering, but

most of

those writers perished in the attempt. However, what they did bequeath

to us is

a radical tradition in literature. INTERVIEWER Do you

consider your own works part of this radical tradition? KERTÉSZ Yes, I do, except I’m not sure whether it is my work or my illness that’s going to kill me now. Well, at least I tried to go on for as long as I could. So obviously I haven’t yet died in the attempt to come to terms with history, and indeed it looks as though I will be dying of a bourgeois disease instead—I am about to die of a very bourgeois Parkinson’s. INTERVIEWER Is writing a means of survival? KERTÉSZ I was able

use my own life to study how somebody can survive this particularly

cruel brand

of totalitarianism. I didn’t want to commit suicide, but then I didn’t

want to

become a writer either—at least not initially. I rejected that idea for

a long

time, but then I realized that I would have to write, write about the

astonishment and the dismay of the witness—Is that what you are going

to do to

us? How could we survive something like this, and understand it, too? To read the rest of this piece, purchase the issue. Note: Bài phỏng

vấn này, đọc thú lắm, và nó liên quan đến "nhà văn sống sót" mà TTT

viện ra khi ông trả lời Le Huu Khoa, trong bài

viết bằng

tiếng Tây, trong Mảng Lưu Vong, La

Part d’Exile: Kinh nghiệm

văn chương của ông trong thời kỳ chiến tranh từ 1954 tới 1975? Ngoài thơ

ra, tôi trải qua hai giai đoạn đánh dấu bằng hai tác phẩm văn xuôi.

Cuốn đầu, Bếp Lửa, 1954, miêu tả không khí Hà-nội

trước 1954; đi và ở đều là những chọn lựa miễn cưỡng, chia lìa hoặc cái

chết. Lập

tức có phản ứng của những nhà văn cách mạng. Trong một bài điểm sách

trên Văn Nghệ, một nhà phê bình hỏi tôi:

"Trong khi nhân dân miền Bắc đất nước ra công xây dựng xã hội chủ

nghĩa,

nhân vật trong Bếp Lửa đi đâu?".

Tôi trả lời: "Anh ta đi đến sự huỷ diệt của lịch sử," mỗi nhà văn là

một kẻ sống sót. (1) INTERVIEWER Kertesz: Có

đấy, nhưng không phải cho mọi người INTERVIEWER Nhưng cho ông?

|

|