|

|

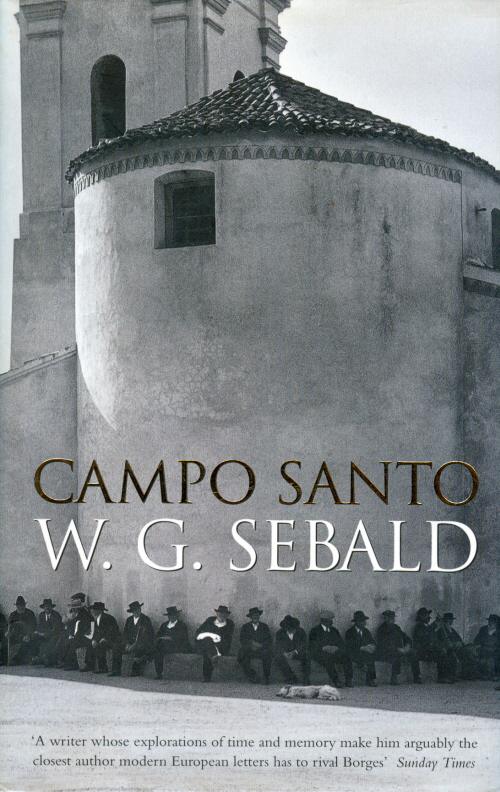

Publisher's

Note Campo Santo

brings together pieces written over a period of some twenty years

touching, in

typical Sebaldian fashion, on a variety of subjects. None has been

previously

published in book form, but the ideas expressed in 'Between History and

Natural

History' will be familiar to some readers - the essay is the

predecessor of the

Zurich lectures which later became the backbone of On the

Natural History of Destruction. Between

History and Natural History On the

literary description of total destruction The trick

if elimination is every

expert's defensive reflex. I drove

through ruined Cologne late

at dusk, with terror of the world and of men and of myself in my heart. To this day

there is no adequate explanation of why the destruction of the German

cities

towards the end of the Second World War was not (with those few

exceptions that

prove the rule) taken as a subject for literary depiction either then

or later,

although significant conclusions could certainly have been drawn from

this

admittedly complex problem. It might, after all, have been supposed

that the

air raids very methodically carried out over the years and directly

affecting

large sections of the population of Germany, as well as the radical

social

changes resulting from the destruction, would have been an incitement

to writers

to set down something about such experiences. The dearth of literary

records

from which anything might be learned of the extent and consequences of

the

destruction which is so obvious to a later generation, although those

involved

clearly felt no need to commemorate it, is all the more remarkable

because

accounts of the development of West German literature frequently speak

of what

they call Trummerrliteratur (the

literature of the ruins). Heinrich Boll, for instance, says of that

genre in a

book written in 19.P: 'And so we write of the war, of homecoming, of

what we

had seen in the war and what we found on returning home: we write of

ruins.'

(1). The same author's Frankfurter

Vorlesungen ['Frankfurt Lectures'] contains the comment: 'Where

would 1945,

that historic moment in time, be without Eich and Celan, Borchert and

Nossack,

Kreuder, Aichinger and Schnurre, Richter, Kolbenhoff, Schroers,

Langgasser,

Krolow, Lenz, Schmidt, Andersch, Jens and Marie Luise von Kaschnitz?

(2) The

Germany of the years 1945-1954 would have vanished long ago had it not

found

expression in the literature of the time.' (3). One may feel a certain

sympathy

for such statements, but they hardly offset the near-incontrovertible

fact that

the literature cited here, which is sufficiently known to have dealt

primarily

with 'personal matters' and the private feelings of its protagonists,

is of

relatively slight value as a source of information on the objective

reality of

the time, more particularly the devastation of the German cities and

the

patterns of psychological and social behavior affected by it. It is

remarkable,

to say the least, that up to Alexander Kluge's account of the air raid

of 8

April 1945 on Halberstadt, published in 1977 as Number 2 in his series

of Neue Geschichten ['New Stories'], there

was no literary work that to any degree filled up this lacuna in German

memory,

which is surely more than coincidental, and that Hans Erich Nossack and

Hermann

Kasack, the only writers who attempted any literary account of the new

historical

factor of total destruction, embarked upon their works in that vein

while the

war was still in progress, and sometimes even anticipated actual

events. In his

reminiscences of Hermann Kasack, Nossack writes: At the end of 1942 or the

beginning of 1943 I sent

him thirty pages of a prose work which after the end of the war was to

become

my story Nekyia. Thereupon Kasack challenged me to a competition in

prose. I

didn't understand what he meant by that; only much later did it become

clear to

me. We were both dealing with the same subject at the time, the

destroyed or

dead city. Today it may seem that it was not too difficult to foresee

the

destruction of our cities. But it is still remarkable that before the

event two

writers were trying to take an objective view of the totally unreal

kind of

reality in which we had to spend years at the time, and in which we

fundamentally still find ourselves, accepting it as the form of

existence

allotted to us. (4) * 'Internal

emigrants' were those people who, while dissociating themselves

intellectually

from the Nazi regime, remained in Germany during the Hitler period. the facades

of the buildings in the surrounding streets still stood, so that a

sideways

glance through the rows of empty windows gave a view of the sky.' (7)

And it

could be argued that the account of the 'lifeless life's of the people

in the

limbo of this twilight kingdom was also inspired by the real economic

and

social situation between 1943 and 1947. There are no vehicles anywhere,

and

pedestrians walk the ruined streets apathetically, 'as if they no

longer felt

the bleak nature of their surroundings'. (9). Others 'could be seen in

the

ruined dwellings, now deprived of their purpose, searching for buried

remnants

of household goods, here salvaging a bit of tin or wire from the

rubble, there

picking up a few splinters of wood and stowing them in the bags they

wore slung

around them, which resembled botanical specimen tins'. (10). There is a

sparse

assortment of junk for sale in the roofless shops: 'Here a few jackets

and

trousers, belts with silver buckles, ties and brightly colored scarves

were

laid out, there a collection of shoes and boots of all kinds, often in

very

poor condition. Elsewhere hangers bore crumpled suits in various sizes,

old-fashioned rustic smocks and jackets, along with darned stockings,

socks and

shirts, hats and hairnets, all on sale and jumbled up together.' (11).

However,

the lowered standard of living and reduced economic conditions that are

evident

as the empirical foundations of the narrative in such passages are not

the

central constituents of Kasack's novel, which by and large mythologizes

the

reality as it was or could be experienced. But the critical potential

of the

type of fiction developed by Kasack, which is concerned with the

complex

insight that even those who survive collective catastrophes have

already

experienced their death, is not realized on the level of myth in his

narrative

discourse; instead, and in defiance of the sobriety of his prose style,

Kasack

aims to present a skilful rationalization of the life that has been

destroyed.

The air raids which caused the destruction of the city appear, in a

pseudo-epic

style reminiscent of Doblin, as trans-real entities. 'As if at the

prompting of

Indra, whose cruelty in destruction surpasses the demonic powers, they

rose,

the teeming messengers of death, to destroy the halls and houses of the

great

cities in murderous wars, a hundred times stronger than ever before,

striking

like the apocalypse.' (12). Green-masked figures, members of a secret

sect who

give off a stale odor of gas and may be meant to symbolize murdered

concentration camp victims, are introduced (with allegorical

exaggeration) in

dispute with the bogeymen of power who, blown up to over life-size,

proclaim a

blasphemous dominion, until they collapse in on themselves, empty husks

in

uniform, leaving behind a diabolical stench. In the closing passages of

the

novel an attempt to make sense of the senseless is added to this mise en scene, which is almost worthy of

Syberberg and owes its existence to the most dubious aspects of

Expressionist

fantasy. A venerable Master Mage sets out the complex preliminary

doctrines of

a combination of Western philosophy and Eastern wisdom. 'The Master

Mage

indicated that for some time the thirty-three initiates had been

concentrating

their forces on opening up and extending the region of Asia, so long

cut off,

for reincarnations, and they now seemed to be intensifying their

efforts by including

the West too as an area for the resurrection of mind and body. This

exchange of

Asiatic and European ideas, hitherto only a gradual and sporadic

process, was

clearly perceptible in a series of phenomena.' (13). In the

course of further pronouncements by the Mage, Kasack's alter ego is

brought to

realize that millions must die in this wholesale operation 'to make

room for

those surging forward to be reborn. A vast number of people were called

away

prematurely, so that they could rise again when the time came as a

growing

crop, apocryphally reborn in a living space previously inaccessible to

them.'

14 The choice of words and terminology in such passages, speaking of

the

opening up 'of the region of Asia, so long cut off', of the benefit of

'European

ideas', and 'living space [Lebensraum]

previously inaccessible' show with alarming clarity the degree to which

philosophical speculation bound to the style of the time subverts its

good

intentions even in the attempt at synthesis. The thesis frequently held

by the

'internal emigrants' that genuine literature had employed a secret

language (15)

under the totalitarian regime is thus proved true, in this as in other

cases,

only in so far as its own code accidentally happened to coincide with

Fascist

style and diction. The vision of a new educational field proposed by

Kasack, as

it also was by Hermann Hesse and Ernst Junger, makes little difference

to that

fact, for it too is only a distortion of the bourgeois ideal of an

association

of the elect operating outside and above the state, an ideal which

found its

ultimate corruption and perfection in the officially ordained Fascist

elites.

When it seems to the archivist at the end of his story, then, 'as if a

sign

formed in the place that the departed spirit had touched with its

finger, a

small stain, a final rune of fate', 16 we are looking at an example

that can

hardly be surpassed of the tendency developing in Kasack's work,

against his

narrative intention, to bury the ruins of the time under the lumber of

an equally

ruined culture once again. Even Hans

Erich Nossack' s description of the destruction of Hamburg, 'Der

Untergang',

which, as we shall see, gives a much more exact account of the real

features of

a collective catastrophe, lapses here and there into the mythologizing

approach

to extreme social circumstances which had become almost habitual since

the time

of the First World War, when realism gave up the ghost. Here too the

writer resorts to the arsenal of the apocalypse, speaking of peaceful

trees

transformed in the beam of searchlights into black wolves 'leaping

greedily at

the bleeding crescent moon', and of infinity blowing at its will

through the

shattered windows, sanctifying the human countenance 'as the place of

transition for the eternal' . (17) Nowhere in Nossack, however, does

this

fateful rhetoric, obstructing our view of the technical enterprise of

destruction, degenerate to the point where he compromises himself

ideologically

as a writer. It is undeniably to Nossack's credit that in his thinking

and in

the writing of this piece of prose, which in many respects is

exceptional, he

largely resists the style of the time. The view of an immemorial city

of the

dead which he presents is thus much closer to reality and has a value

qualitatively different from the account of the same theme in Kasack's

novel. I saw the faces of those

standing beside me in the

vehicle as we drove down the broad road over the Veddel to the Elbe

bridge. We

were like a tourist party; all we needed was a loudspeaker and the

explanatory

chatter of a guide. And we were all at a loss, and could not take in

the

strangeness. Where once your eyes met the walls of buildings, a silent

plain

now extended to infinity. Was it a cemetery? But what beings had buried

their

dead there and then put chimneys on the graves? Nothing grew there but

the

chimneys emerging from the ground like monuments, like dolmens or

admonitory

fingers. Did the dead lying below them breathe the blue ether through those chimneys? And where, among this strange undergrowth, an empty facade hung in the air like a triumphal arch, was it the resting place of one of their princes or heroes? Or was it the remnant of an aqueduct of the ancient Roman kind? Or was all this just the stage set for a fantastic opera? (18) The monumental

theatrical scene of a ruined city presented to an observer passing by

reflects

something of Elias Canetti's later comment on Speer's architectural

plans: for

all their evocation of eternity and their enormous size, their design

contained

within itself the idea of a style of building that revealed all its

grandiose

aspirations only in a state of destruction. The curious sense of

exaltation

that sometimes seems to overcome Nossack at the sight of the

devastation in his

native city is very appropriate to that observation. Only from its

ruins does

the end of the Thousand-Year Reich that intended to usurp the future

become

conceivable. The emotional conflict arising from the fact that total

destruction

coincided with his personal liberation from an apparently hopeless

situation

was not, however, something that Nossack could reduce to a common

denominator.

In view of the utter catastrophe there seems to be something scandalous

about

the 'feeling of happiness' that he experiences on the drive 'towards

the dead

city' as something 'true and imperative', the need 'to cry out

rejoicing: now,

at last, real life begins', (19) and Nossack can justify

it only by cultivating an awareness of shared guilt and responsibility.

These

circumstances also made it impossible for him to let his mind dwell on

the

agents of the destruction. Nossack speaks of a deeper insight that

forbade him

'to think of an enemy who had done all this; he too was at most a tool

of

inscrutable powers that wanted to destroy us'. (20) Like Serenus

Zeitblom* in

his cell in Freising, Nossack feels that the strategy of the Allied air

forces

was the work of divine justice. Nor is this process of revenge solely a

matter

of retribution visited on the nation responsible for the Fascist

regime; it is

also concerned with the need for atonement felt by the individual, in

this case

the author, who has long yearned to see the city destroyed. 'In all

earlier

raids I wished clearly: let it be a very bad one! I felt it so very

clearly

that I might almost say I cried that wish aloud to heaven. It was not

courage

but curiosity to see if my wish would be granted that never let me go

down to

the cellar but held me spellbound on the apartment balcony.' (21) 'And

if it is

the case,' writes Nossack in another passage, 'that I called down the

city's

fate on it to force my own fate to its moment of decision, then I must

also

stand up and confess myself guilty of its fall.' (22) Such explorations

of the

conscience arise from the scruples of the survivors, their sense of

shame at * The

narrator of Thomas Mann's Dr Faustus.

'not being

among the victims', (23) and were later to feature among the central

moral

dimensions of West German literature. Reflections on the guilt of

survival were

probably presented most cogently by Elias Canetti, Peter Weiss and

Wolfgang

Hildesheimer, 24 which suggests that not much might have come of the

process

known in Germany as 'coming to terms with the past' but for the

contribution

made by writers of Jewish origin. There is further evidence in the fact

that in

the years following the fall of the Third Reich, the sense of guilt

expressed

by Nossack was initially transformed into an existential philosophy

which still

nurtured a belief in fate and endeavored to face 'the void . . . with

composure', a philosophy with a concept embracing personal failure, in

which

Nossack too sees 'the appropriate way of death for us'. 25 The crux of

this

resolution of the opposition between destruction and liberation lies in

the

fact that it upholds the promises of Death, which itself appears at the

end of Nossack'

s text as an allegorical figure coming 'through the arch of the old

gateway

every afternoon' , (26) enticing children out to play. The image of

death as a

companion of the writer's imagination is a metaphor for the mourning in

which

the population as a whole could not afford to indulge, as Alexander and

Margarete Mitscherlich explained in their famous essay on the

psychological

disposition of the German nation after the catastrophe - for 'the

mother of the

family still has a great deal of work, she does the laundry, she cooks,

and she

must go down to the cellar from time to time to fetch coal'. (27) The

ironic

detachment here, complementing the melancholy of Nossack's narrative,

demolishes

the claim to the superior significance of death that pervades Kasack's

novel,

and does not deny those who managed to survive the right to a secular

continuation of their existence. Although in

some of its amplifications Nossack's text goes beyond the plain facts

of what

happened, veering into personal confession and mythically allegorical

structures,

it may be understood in its entirety as a deliberate attempt to give as

neutral

as possible an account of an experience exceeding anything in the

artistic imagination.

In an essay of 1961 where Nossack speaks of the influences on his

literary

work, he writes that after reading Stendhal he was anxious to express

himself

'as plainly as possible, without well-crafted adjectives, high-flown

images or

bluff, more like someone writing a letter in almost everyday jargon'.

28 This

stylistic principle proves its worth in his depiction of the ruined

city, in

that it does not allow traditional literary methods which tend to

homogenize

collective and personal catastrophes; Mann's novel Dr

Faustus is the contemporary paradigm. In direct contrast to the

traditional approach to writing fiction, Nossack experiments with the

prosaic genre

of the report, the documentary account, the investigation, to make room

for the

historical contingency that breaks the mould of the culture of the

novel. Where

Kasack's book about the city beyond the river, which in its opening

passages

also tries to maintain the neutrality of an impersonal report, very

soon lapses

into features like those of fiction, Nossack manages to preserve, over

long

tracts of his work, the documentary tone that set an example for the

later

development of West German literature. If familiarity with social and

cultural circumstances

is the crucial prerequisite for both writing and reading novels, then

the

attitude of an agency that simply presents a report conveys a sense of

reality

that appears foreign. That is evident in Nossack's prose work 'Bericht

eines

fremden Wesens uber die Menschen' ['Account of Mankind by a Strange

Creature'],

which is also associated with the themes described above and ascribes

to the

narrator the 'strangeness' in the title, but asks the reader whether

the reason

for it is not a mutation in mankind that makes the author an

anachronistic

figure. The wide distance between the subject and object of the

narrative

process implies something like the perspective of natural history, in

which

destruction and the tentative forms of new life that it generates act

like

biological experiments in which the species is concerned 'to break its

mould

and abjure the name of man' . (29) As the first sentence of his account

tells

us, Nossack witnesses the fall of Hamburg as a spectator. Shortly

before the

air raid on the city of 2 I July 1943 he had gone to spend a few days

in a

village on the Luneburg Heath, fifteen kilometres south of its

outskirts. The

timelessness of the landscape reminds him 'that we come from a fairy

tale and

shall return to a fairy tale again', 30 which in the circumstances

suggests not

so much the idylls of Hermann Lons (the poet of that area) as the

precarious

achievements of the technological civilization that was shortly to

return large

parts of the population to the hunter-gatherer stage of development.

From the

Heath, the approaching destruction of the city appears like a natural

spectacle. Sirens howl 'like cats somewhere in distant villages', the

sound of

the bomber squadrons coming in hovers in the air 'between the clear

constellations and the dark earth', the shapes like 'fir trees'

dropping from

the sky resemble 'red-hot drops of metal flowing' down on the city,

until they

later disappear in a cloud of smoke, 'lit red from below by the fire'.

(31) The

scene thus suggested, still containing aestheticized elements, already

shows

that a 'description' of the catastrophe from its periphery rather than

its

centre is possible. If Nossack's text conveys only a reflection of the

inferno,

his own real evidence begins when the raid is over and the extent of

the

destruction is gradually revealed to him. Even before his return to

Hamburg he

is amazed by the 'constant coming and going' that begins with the

firemen

hurrying to the city's aid from nearby towns, and continues 'on all the

streets

of the region around ... by day and by night' during the throng's

flight from

Hamburg, no one knew where. It was a river for which there was no bed;

almost

silently but inexorably deluging everything, carrying disquiet along

little

rivulets and into the most remote villages. Sometimes fugitives thought

they

could cling to a branch and so get a footing on the bank, but only for

a few

days or hours, and then they threw themselves back into the torrent to

let it

carry them on. None of them knew that they carried restlessness with

them like

a sickness, and everything it touched lost its firm foundation. (32) Later

Nossack comments on his impression that the journeying of the countless

throngs

of people on the move daily was by no means necessary 'to salvage

something or

keep an eye open for relatives ... Yet I would not like to call it mere

curiosity. People simply had no central point . . . and everyone was

afraid of

missing something.' (33) The aimlessly

panic-stricken conduct of the population reported here by Nossack

corresponds

to no social norms, and can be understood only as a biological reflex

set off

by the destruction. Victor Gollancz, who in the autumn of 1945" visited

several cities in the British-occupied zone, including Hamburg, in

order to

make first-hand reports which would convince the British public of the

necessity of rendering humanitarian aid, notes the same phenomenon. He

describes a visit to the Jahn Gymnastics Hall, 'where mothers and

children were

spending the night. They were units in that homeless crowd that goes

milling

about Germany' 'to find relatives" , they said, but really, or mainly,

I

was told, because a restlessness has come over them that just won't let

them

settle down.' (34). The extreme restlessness and mobility to which

Gollancz

testifies were the reactions of a species seeing itself cut off from

its ways

of escape, which biologically speaking always lay ahead of it, and as

preconscious experience those reactions affected the new social dynamic

developing

out of the destruction. Boll, who understood the constant movement

associated

with the war as a very specific aspect of human misfortune, with

peacefully

settled populations returning to the nomadic way of life, ascribes the

post-war

West German liking for speed, and the passion for travel which drives

people

out of that country every year in great droves, to the experiences of a

historical period when whole social groups were removed from the last

secure

factor in their lives, the places where they lived. (35) Literature

tells us

very little more about the archaic behavior that broke through in this

way.

Nossack does indicate that 'the usual disguises' of civilization fell

away as

if of their own accord, and 'greed and fear showed themselves naked and

unashamed'.

(36) The reversion of human life to the primitive, starting with the

fact that,

as Boll remembered later, 'this state began with a nation rummaging in

the

refuse', (37) is a sign that collective catastrophe marks the point

where

history threatens to revert to natural history. In the midst of the

ruined

civilization, what life is left assembles to begin at the beginning

again in a

different time. Nossack notes how unsurprising it seems 'that people

had lit

small fires in the open, as if they were in the jungle, and were

cooking their

food or boiling up their laundry on those fires'. (38) There is not

much

comfort, however, in the fact that in Nossack's account the city, now

reduced

to a desert of stone, soon begins to stir, that trodden paths appear

across the

rubble, linking up - as Kluge remarks - 'to a faint extent with earlier

networks of paths' , (39) for it is not yet certain whether the

surviving

remnants of the population will emerge from this regressive phase of

evolution

as the dominant species, or whether that species will be the rats or

the flies

swarming everywhere in the city instead. The revulsion at this new

life, at the

'horror teeming under the stone of culture' 40 to which Nossack gives

expression in one of the most terrible passages of his text, is a

pendant to

the fear that the inorganic destruction of life by the firestorm which

(according to Walter Benjamin's distinction between bloody and

non-bloody

violence) might yet be reconcilable with the idea of divine justice,

will be

followed by organic decomposition caused by flies and rats, to which in

Kasack's book to the river drawing the line between life and death

'forms no

barrier' . (41) Writing from such an extreme situation required a

redefinition

of the author's moral position, which for Nossack can be justified only

by the

necessity of rendering accounts, or as Kasack puts it the need 'to note

certain

procedures and phenomena before they fall into oblivion'. (42) In such

conditions writing becomes an imperative that dispenses with artifice

in the

interests of truth, and turns to a 'dispassionate kind of speech',

reporting

impersonally as if describing 'a terrible event from some prehistoric

time' . (43)

In an essay he wrote on the diary of Dr Hachiya from Hiroshima, Elias

Canetti

asks what it means to survive such a vast catastrophe, and says that

the answer

can be gauged only from a text which, like Hachiya's observations, is

notable

for precision and responsibility. 'If there were any point,' writes

Canetti,

'in wondering what form of literature is essential to a thinking,

seeing human

being today, then it is this.' (44) The ideal of truth contained in the

form of

an entirely unpretentious report proves to be the irreducible

foundation of all

literary effort. It crystallizes resistance to the human faculty of

suppressing

any memories that might in some way be an obstacle to the continuance

of life.

The outcast, says Nossack, 'dared not look back, since there was

nothing behind

him but fire'. (45). For that very

reason, however, memory and the passing on of the objective information

it

retains must be delegated to those who are ready to live with the risk

of

remembering. It is a risk because, as the following parable by Nossack

shows,

those in whom memory lives on bring down upon themselves the wrath of

others

who can continue to live only by forgetting. He writes of survivors

sitting round

the fire one night: Then one man

spoke in his dream. No one understood what he was saying. But they were

all

uneasy, they rose, they left the fire, they listened fearfully to the

cold dark

around them. They kicked the dreaming man, and he woke. 'I have been

dreaming.

1 must tell you what 1 dreamed. 1 was back with what lies behind us.'

And he

sang a song. The fire burned low. The women began to weep. 'I confess,

we were

human beings!' Then the men said to each other, 'If it was as he

dreamed we would

freeze to death. Let us kill him!' And they killed him. Then the fire

burned

hot again, and everyone was content. (46). The reason

for the murder of memory lies in the fear that Orpheus's love for

Eurydice

might, as Nossack puts it in another passage, (47) turn to a passion

for the

goddess of death; it knows nothing of the positive potential of

melancholy. But

if it is true that 'the step from mourning to being comforted is not

the greatest

step but the smallest' , (48) then the proof is in that passage of

Nossack' s

account where he remembers the truly infernal death of a group of

people who

burned in a bomb-proof shelter because the doors had jammed and coal

stored in

the rooms next to it caught fire. 'They had all fled from the hot walls

to the

middle of the cellar. They were found there crowded together, bloated

with the

heat. ' (49). The laconic comment reminds us of the Homeric lines about

the

fate of the hanged maids: 'So the women's heads were trapped in a line,

/

nooses yanking their necks up, one by one / so all might die a pitiful,

ghastly

death ... / they kicked up heels for a little - not for long.' (50).

The

comfort of language evoking pity takes the reader, in Nossack's text,

in very

concrete terms straight from the horror of that coal cellar into the

following

passage about the convent garden. 'We had heard the Brandennburg

concertos

there in April. And a blind woman singer performed; she sang: Die schwere Leidenszeit beginnt nun abermals

- ["The time of suffering now begins once more"]. Simple and

self-assured,

she leaned against the harpsichord, and her unseeing eyes looked past

those

trivialities for which we already feared, past them and perhaps to the

place

where we now stood, with nothing but a sea of stones around us.’ (51).

Here

again, of course, we have a construction - a metaphysical construction

- placed

on the meaning. But the way in which Nossack puts his hopes in the will

to tell

the truth, and helps to overcome the tension between two poles by his

un-emotive

style, may justify such a conjecture. * Comparison

of Kasack's novel with Nossack's factual account also shows that an

attempt to

write a literary account of collective catastrophes inevitably, if it

is to

claim validity, breaks out of the novel form that owes its allegiance

to

bourgeois concepts. At the time when these works were produced the

implications

for the technique of writing could not yet be foreseen, but they became

increasingly clear as West German literature absorbed the debacle of

recent

history. Consequently, Alexander Kluge's highly complex and at first

sight

heterogeneous book Neue Geschichten.

Hifte 1-18 ['New Stories. Nos. 1- 18'], published in 1977, resists

the

temptation to integrate that is perpetuated in traditional literary

forms by

presenting the preliminary collection and organization of textual and

pictorial

material, both historical and fictional, straight from the author's

notebooks,

less to make any claim for the work than as an example of his literary

method.

If this procedure undermines the traditional idea of a creative

writerbringing

order to the discrepancies in the wide field of reality by arranging

them in

his own version, that does not invalidate his subjective involvement

and commitment,

the point of departure of all imaginative effort. Indeed, the second of

the

'new stories', describing the air raid of 8 April 1945" on Halberstadt,

is

a model in this respect, showing how personal involvement in collective

experience,

a crucial feature of Nossack' s writing too, can be made at least a

heuristically meaningful concept through analytic historical

investigations,

relating it to immediately preceding events and later developments, to

the

present and to possible future perspectives. Kluge, who grew up in

Halberstadt,

was thirteen years old at the time of the air raid. 'When a

high-explosive bomb

drops you notice it,' he says in his introduction to the stories,

adding, 'On 8

April 1945 something of that kind fell ten metres away from me. '52

Nowhere

else in the text does the author refer directly to himself. The tone of

his

account of the destruction of his native town is one of research into

the past;

the traumatically shocking experiences to which those affected reacted

with

complex processes of amnesiac suppression are brought into a present

reality

shaped by that buried history. In precisely the opposite way from

Nossack,

Kluge's retrospective presentation of what happened follows not what

the author

saw with his own eyes, or what he may still remember of it, but events

peripheral to his own existence past and present. For the aim of the

text as a

whole, as we shall see, depends on the fact that experience in any real

sense

was actually impossible in view of the overwhelming speed and totality

of the

destruction; it could be acquired only indirectly, by learning about it

later. Kluge's

literary record of the air raid on Halberstadt is also a model of its

kind from

another objective viewpoint, where it studies the question of the

'meaning'

behind the methodical destruction of whole cities, which authors like

Kasack

and Nossack either omit for lack of information and out of a sense of

personal

guilt, or endow with mystical significance as divine justice and long

overdue

punishment. If the strategy of the area bombing of as many German

cities as

possible could not be justified by military objectives, which can

hardly be

denied today, then as Kluge's book shows the special case of the

horrible

devastation of a medium-sized town, of no importance either

strategically or to

the war economy, must raise very serious questions about the factors

determining the dynamic of technological warfare. Kluge's account

contains an

interview with a high-ranking Allied staff officer by a correspondent

for the Neue Ziircher Zeitung. Both the officer

and the journalist flew with the raid as observers. The section of the

interview quoted by Kluge deals primarily with the question of 'moral

bombing',

which Brigadier General Williams explains by reference to the official

doctrine

on which the air raids were based. When asked, 'Do you bomb for moral

reasons

or are you bombing the enemy's morale?' he replies, 'We are bombing the

enemy's

morale. The population's will to resist must be broken by the

destruction of

their city.' When pressed further, however, he admits that morale does

not seem

to be affected by the bombs. Obviously

morale is not located in the head or here [he points to his solar

plexus) but

somewhere among the individuals or populations of the cities concerned.

We have

investigated that, and it's known to the staff ... Obviously it's not

in the

head or the heart, and that makes sense anyway, since people who have

been

killed by the bombs aren't thinking or feeling anything. And people who

escape

a raid like that in spite of our best efforts clearly don't take their

impressions of the disaster with them. They take all the luggage they

can, but

they seem to leave behind their instant impressions of the raid itself.

(53). While

Nossack offers us no conclusions about the motives and reasons for the

act of

destruction, Kluge, both here and in his book on Stalingrad, tries to

account

for the organizational structure of such a disaster, showing how even

when the

facts have become clearer the catastrophe continues on its old course

because

of administrative apathy, and there is no chance of raising the

difficult

question of ethical responsibility. Kluge's

account begins by showing the total inadequacy of all those modes of

behavior

socially pre-programmed into us in the face of a catastrophe which is

irrevocably unfolding. Frau Schrader, an employee of long standing at

the

Capitol cinema in Halberstadt, finds the usual course of the Sunday

programme -

it has been maintained for years, and the movie showing today, 8 April,

is an

Ucicky film starring Wessely, Petersen and Horbiger* - disrupted by the

prior

claims of a programme of destruction. Her panic-stricken attempts to

create

some kind of order and perhaps clear up the rubble in time for the two

o'clock

matinee tellingly illustrates the extreme discrepancy between the

active and

passive fields of action involved in the catastrophe, leading the

writer and

his readers to the quasi-humorous observation that 'the devastation of

the

right-hand side of the auditorium ... [had] no meaningful or

dramaturgical connection

with the film being screened' .54- There is similar irrationality in

the

description of a troop of soldiers sent as an emergency force to dig up

and

sort out '100 corpses, some of them badly mutilated, partly from the

ground,

partly from visible depressions in it that had once been part of a

shelter' , (55)

with no idea of the purpose of 'this operation' in the present

circumstances.

The unknown photographer intercepted by a military patrol who claims

that he

wants 'to record the burning city, his own home town, in its hour of

misfortune' , (56) resembles Frau Schrader in following his

professional

instincts. The only reason why his declared intention of * A film by the director Gustav Ucicky, starring the actors Paula Wessely, Peter Petersen and Attila H6rbiger. The film was called Heimkehr ['Homecoming'). recording

the very end is not absurd is that the pictures he took, which Kluge

added to

his text and numbered 1 to 6, have survived, as he could hardly have

expected

at the time. The women on watch in the tower, Frau Arnold and Frau

Zacke,

equipped with folding chairs, torches, thermos flasks, packets of

sandwiches, binoculars

and radio sets, are still dutifully reporting as the tower itself seems

to move

beneath them and its wooden cladding begins to burn. Frau Arnold dies

under a mountain

of rubble with a bell on top of it, while Frau Zacke lies for hours

with a

broken thigh until she is rescued by people fleeing from the buildings

on the

Martiniplan. Twelve minutes after the air raid warning, a wedding party

in the

Zum Ross inn is buried, together with all its social differences and

animosities - the bridegroom was 'from a prosperous family in Cologne',

his

bride, from Halberstadt, 'from the lower town'. (57) These and many of

the

other stories making up the text show how, even in the middle of the

catastrophe, individuals and groups were still unable to assess the

real degree

of danger and deviate from their usual socially dictated roles. Since,

as Kluge

points out, normal time and 'the sensory experience of time' were at

odds with

each other, those affected 'could not have devised practicable

emergency

measures ... except with tomorrow's brains' . (58) This divergence, for

which

'tomorrow's brains' can never compensate, proves Brecht's dictum that

human

beings learn as much from catastrophes as laboratory rabbits learn

about

biology, (59) which in turn shows that the autonomy of mankind in the

face of

the real or potential destruction that it has caused is no greater in

the

history of the species than the autonomy of the animal in the

scientist's cage,

a circumstance that enables us to see why the speaking and thinking

machines

described by Stanislaw Lem wonder if human beings can actually think or

are

merely simulating that activity, and drawing their own self-image from

it. (60). Although it

seems impossible, as a result of the socially and naturally determined

human

capacity to learn from experience, for the species to escape

catastrophes generated

by itself except purely by chance, studying the conditions in which

destruction

took place after the event is not pointless. Instead, the retrospective

learning process - and this is the raison

d'être of Kluge's account, compiled thirty years after the

incidents he

describes is the only way of deflecting human wishful thinking towards

anticipation of a future not already governed by the fears arising from

suppressed experience. The primary school teacher Gerda Baethe, a

character in

Kluge's text, has similar ideas. It is true, the author comments, that

to

implement a 'strategy from below' such as Gerda has in mind would have

required

'70,000 determined school teachers, all like her, each of them teaching hard for twenty years from 1918

onwards, in every country that had fought in the war'. (61). Despite

the ironic

style, the prospect suggested here of an alternative historical

outcome,

possible in certain circumstances, is a serious call to work for the

future in

defiance of all calculations of probability. Central to Kluge's

detailed

description of the social organization of disaster, which is

pre-programmed by

the ever-recurrent and ever intensifying mistakes of history, is the

idea that

a proper understanding of the catastrophes we are always setting off is

the

first prerequisite for the social organization of happiness. However,

it is

difficult to dismiss the idea that the systematic destruction Kluge

sees

arising from the development of the means and modes of industrial

production

hardly seems to justify the abstract principle of hope. The

construction of the

air war strategy in all its monstrous complexity, the transformation of

bomber

crews into professionals, 'trained administrators of war in the air' ,

the

necessity of countering, as far as possible, any personal perceptions

they

might have such as 'the neat and tidy fields below them, or any

confusion of

the sight of urban streets and squares with impressions of home', and

of

overcoming the psychological problem of keeping the crews interested in

their

tasks despite the abstract nature of their function, the problems of

conducting

an orderly cycle of operations involving' 2 00 medium-sized industrial

plants'

(62) flying towards a city, the technology ensuring that the bombs

would cause

large-scale fires and firestorms - all these factors, which Kluge

studies from

the organizers' viewpoint, show that so much intelligence, capital and

labor

went into the planning of such destruction that, under the pressure of

all the

accumulated potential, it had to

happen in the end. The central point of Kluge's comments is to be found

in a

1952 interview between the Halberstadt journalist Kunzert, who had gone

west

with the British troops in 1945, and Brigadier Frederick L. Anderson of

the US

Eighth Army Air Force. In this interview Anderrson tries, with some

patience,

to answer what from the professional military viewpoint is the naive

question

of whether hoisting a white flag made from six sheets from the towers

of St

Martin's church in good time might have prevented the bombing of the

city. His

comments, initially dealing with military logistics, culminate in a

statement

illustrating the notorious irrationality to which rational argument can

lead.

He points out that the bombs they had brought were, after all,

'expensive

items'. 'In practice, they couldn't have been dropped over mountains or

open

country after so much labor had gone into making them at home. ' (63)

The

result of the prior claims of productivity, from which, with the best

will in

the world, neither responsible individuals nor groups could dissociate

themselves, is the ruined city laid out before us in one of the

photographs

included in Kluge's text. The caption he gave it is from Marx: 'We see

how the

history of industry and the now objective existence of industry have

become the

open book of the human consciousness, human psychology perceived in

sensory

terms ... ' (Kluge's italics). The

reconstruction that Kluge was thus able to make of the disaster, in far

more

detail than the summary of it given here, can be likened to the

revelation of

the rational structure of something experienced by millions of human

beings as

an irrational blow of fate. It almost seems as if Kluge were responding

to the

question put by the allegorical figure of Death in Nossack' s Interview mit dem Tode ['Interview with

Death'] to his interlocutor: 'If you like you can see how I go about my

business. There's no secret to it. The fact that there is no secret is

the

point. Do you understand me?, (64). Death, introduced to us in this

text as a

suave entrepreneur, explains to his listener, with the same ironic

patience as

is evident in Brigadier Anderson's attitude, that fundamentally

everything is

just a question of organization, and organization manifested not merely

in the

collective catastrophe but in all areas of daily life, so that to find

out its

secret all you need to do is visit a tax office or some similar civil

service

department. In Kluge's work, this very link between the vast extent of

the

destruction 'produced' by human beings and the realities we experience

daily is

the point upon which the author's didactic intention turns. Kluge

reminds us

all the time, and in every nuance of his complex linguistic montages,

that

merely maintaining a critical dialectic between past and present can

lead to a

learning process which is not fated in advance to come to a 'mortal

conclusion'. The texts with which Kluge seeks to promote this aim

correspond,

as Andrew Bowie has pointed out, (65) neither to the pattern of

retrospective

historiography nor to the fictional story, nor do they try to offer a

philosophy of history. Instead, they are a form of reflection on all

these

methods of ours for understanding the world. Kluge's art, to use the

term in

another way here, consists in using details to illustrate the main

current of

the dismal course so far taken by history. For instance, there is his

mention

of the fallen trees in the Halberstadt town park, 'where silk-moth

caterpillars

had lived when they were planted in the eighteenth century', and the

following

passage: (Number 9

Domgang) In the windows stood a selection of tin soldiers, which had

fallen

over immediately after the raid, the rest of them being packed away in

boxes

stored in cupboards, 12,400 men in all, Ney's Third Corps as they

desperately

advanced through the Russian winter towards the eastern stragglers of

the

Grande Armée. They were put out on display once a year, during Advent.

Only

Herr Gramert himself could arrange the company of soldiers in their

correct

order. In his terrified flight, leaving his beloved soldiers, he has

been

struck on the head by a burning beam, and can form no further plans.

The

apartment at Number 9 Domgang, with all its marks of Gramert's personal

style,

lies quiet and intact for another two hours, except that it grows

hotter and

hotter during the afternoon. Around five o' clock it catches fire and

so do the

tin soldiers, who melt into lumps of metal in their boxes. (66) A

briefer

didactic fable than this could hardly be written. Kluge's way of

providing his

documentary material with vectors through his presentation of it

transfers what

he quotes into the context of our own present. Kluge 'does not allow

the data

to stand merely as an account of a past catastrophe,' writes Andrew

Bowie; 'the

most unmediated document ... loses its unmediated character via the

processes

of reflection the text sets up. History is no longer the past but also

the

present in which the reader must act. ' (67) The information that

Kluge's style

thus imparts to readers about the concrete circumstances of their

present

existence, and possible prospects for the future, marks him out as an

author

who, on the perimeter of a civilization to all appearances intent on

its own

end, is working to revive the collective memory of his contemporaries

who 'with

the obviously inborn desire for narrative, [have] lost the

psychological power

to remember even within the destroyed city itself'. 68 It seems likely

that

only his preoccupation with this didactic business enables him to

resist the

temptation to offer an interpretation of recent historical events

purely in

terms of natural history, just as elements of the science fiction genre

which

knows all along what the end will be appear again and again in his

work.

Instead, he interprets history in a way rather like, for instance,

Stanislaw

Lem's: as the catastrophic consequence of an anthropogenesis based from

the

first on evolutionary mistakes, a consequence that has long been

foreshadowed

by the complex physiology of human beings, the development of their

hypertrophic

minds, and their technological methods of production.

|