|

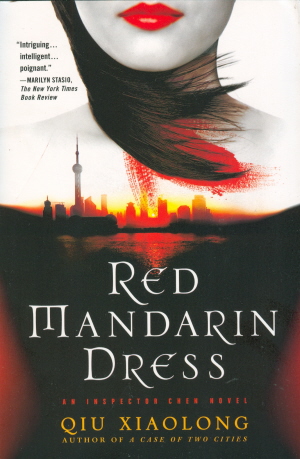

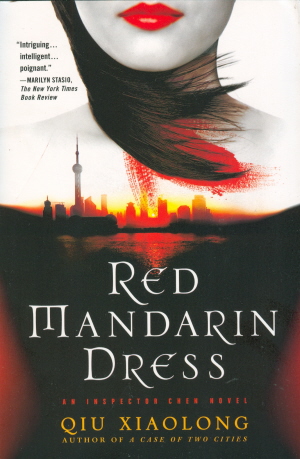

TLS đọc Áo

Đỏ Tiểu Thư Con Gái Nhà Quan

Monkey brains again

JONATHAN MIRSKY

Qiu Xiaolong

RED MANDARIN DRESS

An

Inspector Chen novel 320pp.

Sceptre.£17.99. 9780340935163

Someone

is murdering pretty

young women in Shanghai,

and only on Thursdays. Chief Inspector Chen Cao prowls the streets and

alleys

of the partly modern city, which vibrates with the quick-buck energy

and glitz

of post-Mao China,

and strays into its older shabbier neighborhoods where the Gang of Four

¸remembered with horror - terrified Mao's enemies during the Cultural

Revolution. Chen, a handsome bachelor, attractive to women but

resistant to

their advances, a connoisseur of live shrimp soup and monkey brains,

and a

scholar of eighth-century literature, is above all a dogged copper.

The murderer dresses his

victims' dead bodies in tight, high-slitted, red silk gowns of a kind

not seen

in Shanghai

for

over forty years. He dumps the corpses in public places where he could

easily

get caught, and seems to have handled them sexually, though without

rape. Panic

begins to spread and the police start to look inept. The upper levels

of the

police department hate scandal, but the officers are as blockheaded as

Conan

Doyle's Inspector Lestrade.

As usual, Chen's pursuit of

the killer takes him through the city's high-rolling restaurants, dance

halls,

and bathhouses, all staffed by lovely available girls; he also visits

the

humble street stalls where he can always find his favorite foods. It is

a

characteristic of the Inspector Chen novels that nearly everyone can

quote

ancient Chinese poetry, while also remembering snippets of clues that

keep

Chen's nose pressed to the scent.

The last quarter of Red

Mandarin Dress, after the pretty young policewoman used as a decoy to

lure the

murderer falls into his clutches, is frightening. During the denouement

with

the chief suspect, Chen uses "cruel food" - a turtle slowly boiling

to death - to help break him down. Qiu Xiaolong, who has lived in the United States

since 1988, has PhD, but his English remains a bit awkward. Somehow

this adds

to the atmosphere.

TLS 25 Tháng Giêng, 2008

*

Tôi

viết để trả thù cho Lưu Quang Vũ…

Gấu đọc, và nhân đang đọc một bài điểm sách về một tay chuyên viết

trinh thám người Hoa, Qiu Xialong, ông

cũng viết như thế, trong thư gửi độc giả: Tặng cho tất cả những người

đã đau khổ vì Mao —“For all those suffered

under Mao.”

Tình cờ Gấu đọc tờ Điểm Sách London, mới biết tới Qiu. Cuốn đầu tay của

ông được coi là số 1, bởi giới báo chí, trong có tờ Báo Phố Tường: Một

trong năm cuốn số 1 của mọi thời!

Nhưng, không phải số 1 về tiểu thuyết trinh thám, mà là về chính trị!

Khen như thế mới bảnh chứ!

Khen cũng bảnh, mà được khen lại càng bảnh!

Một cuốn nữa, trong số năm cuốn số 1, tiểu thuyết chính trị, là Bóng Đêm Giữa Ban Ngày của Koestler!

Cuốn đầu tay của Qiu: Cái chết của

một Nữ Hồng Vệ Binh [tạm dịch, không biết có đúng không cái tít

bằng tiếng Anh, Death of a Red

Heroine].

Cái tít này, là từ cái tít Hồng Lâu

Mộng mà ra, theo người điểm, trên Điểm Sách London, số 18 Tháng

Chạp, 2008, khi đọc cuốn mới nhất của Qiu: Red Mandatin Dress. Ông này, quái,

vì bản đầu tay cho ra lò, cho Tây Phương, là bản dịch tiếng Tây: As before, the

French edition came out first. Ông "còn" là một thi sĩ

*

When

Qiu Xiaolong was a boy in Shanghai,

Red Guards loyal to Mao Zedong ransacked his parents' home. The thugs

took jewelry, books and anything else associated with a bourgeois

lifestyle. But they left a few photo magazines. In one, Qiu saw a

picture of a woman wearing a red qipao, the form-hugging Chinese dress

that became an emblem of capitalist decadence during the Cultural

Revolution.

Decades later, the stirred memory of that photo suggested the plot of

Qiu's Red Mandarin Dress, the

fifth and latest of his popular, Shanghai-set Inspector Chen detective

novels. This time, Qiu's hero, a cop and poet, is on the trail of a

serial killer who dresses his female victims in tailored qipao dresses

— a macabre gesture freighted with political meaning. As in the

previous books, the investigation leads Inspector Chen to a brutal

legacy from the past, for even the most vicious of Qiu's criminals are

victims of China's

bloody history. So, incidentally, are many of the people close to the

author. "My mother had a nervous breakdown at the beginning of the

Cultural Revolution and she never really recovered," Qiu says. "But I

also have friends who suffered even worse things. I'm not saying

they're dead or anything. But they're really ruined. Their life,

dreams, career — gone."

Time

Khi Qiu còn là một đứa trẻ ở Thượng Hải, Hồng Vệ Binh

trung thành với Mao đã lục soát nhà cha mẹ ông. Chúng lấy đi nữ trang,

sách vở, và bất cứ một thứ gì liên quan tới cuộc sống trưởng giả, nhưng

vứt lại vài tờ báo hình. Trong một tờ, Qiu nhìn thấy bức hình một người

đàn bà bận áo xẩm đỏ, thứ áo đặc biệt của người TQ, sau trở thành biểu

tượng của sự sa đọa thoái hoá của tư bản trong thời kỳ Cách Mạng Văn

Hóa.

“Lần đầu nhìn thấy bức hình, tôi sững sờ vì vẻ đẹp,” Qiu nói, lúc này

ông 54 tuổi, trông thư sinh nho nhã như một giáo sư trung học. “Cũng là

tự nhiên khi tôi nghĩ rằng, những con người ở trong những bức hình như

thế này từ một gia đình có gốc rễ trưởng giả, và như thế, chắc là họ đã

chịu đựng rất nhiều đau khổ trong thời kỳ Cách Mạng Văn Hóa. Chuyện gì

đã xẩy ra cho họ.

Nhiều chục năm sau, kỷ niệm về bức hình vẫn khuấy động trí tưởng của

ông, và là nguồn hứng khởi khiến ông viết “Áo đỏ tiểu thư” [tạm dịch

Red Mandarin Dress]

Mẹ tôi sụm xuống, khi Cuộc Cách Mạng Văn Hoá nổ ra, và chẳng bao giờ

hồi phục. Nhưng tôi có bạn bè còn khốn đốn hơn nhiều. Tôi không nói, họ

chết. Nhưng họ hoàn toàn tiêu ma, điêu tàn, huỷ diệt. Đời của họ, mộng

của họ, nghề nghiệp của họ. Đi hết.

Một nhà văn nữ, ra đi từ Miền Bắc, có một loạt bài về một miền đất, khi

nó chưa đi cả, đi hết. Thay vì cái áo dài tiểu thư của một cô xẩm, như

của Qiu, thì là một cái bát cổ.

Thứ dễ vỡ nhất.

Mấy bữa

dính 2 cú bão, rớt, tính đi thăm cố đô Lèo đành nằm chờ, và ngốn hết

cuốn

trên.

Tuyệt cú mèo!

Bestseller, thành ra nhiều tình tiết, lớp lang, có vẻ rườm rà, nhưng ở

trung

tâm, là một câu chuyện tình thê lương, nức nở, đúng thứ của thời đại

chúng ta:

Anh Trương Chi ở đây, là một tên đồ tể, nhờ Cách Mạng Văn Hóa, lên làm

Trùm Đảng

“VC” /TQ, tại một địa phương. Em, mới lớn, dân thành phố, mê Đảng như

điên, đẹp

như tiên, tình nguyện đi về miền quê, sống với nhân dân, gặp tên đồ tể,

làm sao

tha, thế là bị nó hiếp, nó bắt phải làm vợ nó...

Trong khi

đám thanh thiếu niên cùng thời, vỡ mộng, chuồn về thành phố, em hết

đường về...

Cái tít cuốn truyện cũng không dễ dịch, phải đọc mới ồ một tiếng, giống

cái tít

Moon Palace.

*

xiu xiu

Anh Tru xem

phim Xiu Xiu chua ? Cung la mot co be di ve vung que cong tac, muon ve

thanh

pho ma khong ve duoc . Phim do Joan Chen dao dien

Chua coi

Trong truyen Loyal, the luong

lam. Tu tu ke tiep…

Khi nao xem

xong Xiu Xiu, The sent down girl thi nho so sanh xem truyen nao the

luong hon

truyen nao .

Phim duoc

nhieu giai thuong dien anh .

Coi review,

thấy

có khác. Truyện bao quát hơn nhiều. Anh cớm giỏi nghề cớm, nghề văn,

nghề

thơ; những chuyển đoạn, thường là bằng thơ, của, thí dụ, Lý Thương Ẩn,

'gặp đã

khó, xa lại càng khó', ‘kiến nan, biệt diệc nan’...

Vì là truyện trinh

thám, nên còn có băng đảng, xuất cảng người, trùm mafia Á ở Mẽo….

Mấy dòng nhạc sau đây, mà

chẳng tuyệt sao:

"You like to

say you are a grain of sand, / occasionally fallen into my eyes, in

mischief. /

You would rather have me weep by myself / than to have me love you, /

and then

you disappear in the wind / like the grain of sand ..."

White Cloud also quoted a couplet from Li

Shangyin, the bard of star-crossed lovers, whispering in his ear, "It is

difficult to meet and to part, too. / The east wind languid, and the

flowers. She said it to evocative effect

as the song was coming to a stop, her hand lingering in his.

He chose to

comment on the poem, "A brilliant juxtaposition of an image with a

statement, creating a third dimension of poetic association."

"Isn’t that

called Xing in the Book of Songs?"

Xing does

not specify the relationship between the image and the statement,

leaving more

room for a reader's imagination,” he expounded. He had no problem

talking to

her poetry.

“Thank you.

You're really special."

'"Thank

you. You're marvelous," he echoed in his best-dancing-school manner,

bowing before he moved back to the sofa.

["Anh nói anh như hạt cát vô tình lạc vào

mắt em/Thà anh làm em khóc,

thay vì làm em thương anh/ rồi anh bỏ đi như hạt cát bay theo gió.."

Rồi Bạch Vân thì thầm vào tai anh, dòng thơ của Lý Thương Ẩn, thi

sĩ của những cặp tình trắc trở, Gặp

nhau đã khó, xa nhau lại càng khó/Gió đông

rên rỉ khiến lá rụng…

Chàng cớm bèn lèm bèm về mấy dòng thơ, “một hình

ảnh/ một nhận xét,

đặt kế bên nhau mới đẹp làm sao, và từ đó tạo ra chiều thứ ba cho kết

hợp thi

ca’"....

Cái này gọi là Xing, trong Kinh Thi, phải không?

Xing không xác

định liên hệ giữa hình ảnh và nhận xét, để dành

chỗ cho sức tưởng tượng của người đọc..

Anh cớm Chen này phán về

thơ hay hơn Thầy Cuốc, theo Gấu!]

Cái

làng cô bé 'văn công trung kiên' tới sống, tới thời kinh tế thị trường,

đa số

xuất cảnh theo diện mafia... làm Gấu nhớ đến một làng hình như ở gần

Huế thì

phải, cũng đi hết, còn leo teo vài người ở lại, sống bằng tiền từ nước

ngoài

gửi về, như những người giữ đền, nhang khói hồn ma, ‘chết trong cuộc

chiến và

sống chẳng biết ngày nào về’...

Cô

gái này bảnh hơn Xiu Xiu nhiều. Cô không hề có ý nghĩ trở về lại

thành

phố, dù gia đình hết sức năn nỉ.. Là một nữ văn công chuyên trình diễn

màn múa

giống như người Việt mình múa nón, trên nón có chữ, tất cả xếp lại

thành lời

chào mừng, thề một lòng một dạ với Bác Mao, cái tít cuốn truyện là vậy,

A Loyal

Character Dancer. Cô được coi là 'nữ hoàng', 'queen' của Đội múa.

Anh cớm mê thơ, và nhờ mê thơ mà phá được vụ án, cùng với cộng tác

viên, partner,

là một nữ cảnh sát Mẽo, có nhiệm vụ qua TQ đưa cô gái qua Mẽo, gặp lại

anh

chồng đồ tể, Trùm VC/TQ ngày nào, khi thất sủng, chuồn qua Mẽo, làm

găng tơ,

đầu thú FBI, tình nguyện tố cáo Trùm băng đảng Mafia Á, với điều kiện

phải cho

cô vợ của anh qua Mẽo đoàn tụ, mặc dù anh ta chẳng yêu thương gì vợ...

A Loyal

Character Dancer có một kết thúc có hậu, không ‘thê lương’: người nữ

văn

công, ‘tiếng hát át tiếng bom’ của TQ được cứu chuộc nhờ thơ ca, và qua

nó, là

mối tình thuở học trò, khi cô còn đang ở đỉnh cao của danh vọng, một Nữ

Hồng Vệ

Binh trung kiên, một nữ hoàng nhan sắc… Và người yêu cô, thầm lén, lẽ

dĩ nhiên,

là con của một tay thuộc phía kẻ thù của nhân dân. Cái đoạn 'kể trong

đêm khuya' sau

đây, của anh chàng si tình, là một trong những trang đẹp nhất của cuốn

truyện:

Liu entered

high school in 1967, at a time when his father, an owner of a perfume

company

before 1949, was being denounced as a class enemy. Liu himself was a

despicable

"black puppy" to his schoolmates, among whom he saw Wen for the first

time. They were in the same class. Like others, he was smitten by her

beauty,

but he never thought of approaching her. A boy from a black family was

not

considered worthy to be a Rep Guard. That Wen was a Red Guard cadre

magnified

his inferiority. Wen led the class in singing revolutionary songs, in

shouting

the political slogans, and in reading Quotations from Chairman Mao,

their only

textbook at the time. So she was real: more like the rising sun to him,

and he

was content to admire her from afar.

That year

his father was admitted to a hospital for eye surgery. Even there,

among the

wards, Red Guards or Red Rebels swarmed like raging wasps. His father

was

ordered to stand to say his confession, blindfolded, in front of

Chairman Mao picture.

It was an impossible task for an invalid who was unable to see or move.

So it

was up to Liu to help, and first, to write the confession speech on

behalf of

the old man. It was a tough job for a thirteen-year-old boy, and after

spending

an hour with a splitting headache, he produced only two or three lines.

In

desperation, clutching his pen, he ran out to the street, where he saw

Wen

Liping walking with her father. Smiling, she greeted him, and her

fingertips

brushed against the pen. The golden top of the pen suddenly began to

shine in

the sunlight. He went back home and finished the speech with his one

glittering

possession in the world. Afterward, he supported his father in the

hospital,

standing with him like a wooden prop, not yielding to humiliation,

reading for

him like a robot It was a day that contained his brightest and blackest

moment.

Their three

years in high school flowed away like water, ending in the flood of the

educated youth movement. He went to Heilongjiang Province with a group

of his

schoolmates. She went to Fujian by herself. It was on the day of their

departure, at the Shanghai railway station, that he experienced the

miracle of

his life, as he held the red paper heart with her in the loyal

character dance.

Her fingers lifted up not only the red paper heart, but also raised him

from

the black puppy status to an equal footing with her.

Life in

Heilongjiang was hard. The memory of that loyal character dance proved

to be an

unfailing light in that endless tunnel. Then the news of her marriage

came, and

he was devastated. Ironically, it was then that he first thought

seriously

about his own future, a future in which he imagined he would be able to

help

her. And he started to study hard.

Like others,

Liu came back to Shanghai in 1978. As a result of the self-study he had

done in

Heilongjiang, he passed the college entrance examination and became a

student

at East China Normal University the same year. Though overwhelmed with

his

studies, he made several inquiries about her. She seemed to have

withdrawn.

There was no information about her. During his four years at college,

never

once did she return to Shanghai. After graduation, he got a job at

Wenhui

Daily, as a reporter covering Shanghai industry news, and he started

writing

poems. One day, he heard that Wenhui would run a special: story about a

commune

factory in Fujian Province. He approached the chief editor for the job.

He did

not know the name of Wen's village. Nor did he really intend to look

for her.

Just the idea of being somewhere close to her was enough. Indeed, there's no story without coincidences.

He was shocked when he stepped into the workshop of the factory.

After the

visit, he had a long talk with the manager. The manager must have

guessed

something, telling him that Feng was notoriously jealous, and violent.

He

thought a lot that night. After all those years, he still cared for her

with

unabated passion. There seemed to be a voice in his mind urging: Go to her. Tell her everything. It may not

be too late.

But the

following morning, waking up to reality, he left the village in a

hurry. He was

a successful reporter, with published poems and younger girlfriends. To

choose

a married woman with somebody else's child, one who was no longer young

and

beautiful-he did not have the guts to face what others might think.

Back in

Shanghai, he turned in the story. It was his assignment. His boss

called it

poetic. "The revolutionary grinder polishing up the spirit of our

society." The metaphor was often quoted. The story must have been

reprinted in the Fujian local newspapers. He wondered if she had read

it. He

thought about writing to her, but what could he say? That was when he

started

to conceive the poem, which was published in Star magazine, selected as

one of

the best of the year.

|

|