|

Hongkong,

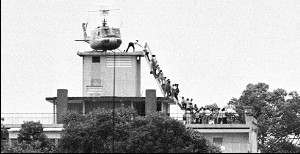

29 tháng Tư, 2005. Ba mươi

năm trước tôi thật

may khi chụp được tấm hình ghi lại cảnh tượng Sài Gòn rơi vào tay VC

trong lúc

trực thăng Mỹ bốc người từ mái tòa Đại Sứ Hoa Kỳ. Nhưng, như rất nhiều

điều về

cuộc chiến VN, chuyện tưởng vậy mà không phải vậy. Nói rõ hơn, bức hình

không

chụp từ trên mái Tòa Đại Sứ, mà từ mái một building, ở trung tâm Sài

Gòn, nơi

đám đầu sỏ CIA trú ngụ. Đó là

ngày Thứ Ba, 29 Tháng

Tư, 1975. Tin đồn về chuyến di tản chót ra khỏi Sài Gòn thì đã có từ

mấy tuần

lễ trước. Hàng ngàn người, người Mỹ dân sự, người Việt, và người thuộc

các nước

thứ ba, sẽ được máy bay chở hàngb hoá bốc đi tại sân bay Tân Sơn Nhất,

và sẽ

hướng tới những căn cứ của Mỹ như ở Guam, Okinawa, hay đâu đó. Mọi

người đều

biết quân đội Bắc Việt đang xiết vòng vây quanh thành phố, và việc thất

thủ chỉ

còn là ngày một ngày hai. Vào khoảng 11 giờ sáng, một cú điện thoại từ

Brian

Ellis, trưởng phòng CBS, người lo việc phối hợp trong công tác di tản

đám báo

chí ngoại quốc. Lên đường! Điểm tụ

tập là trên đường Gia

Long, đối diện nhà thương Grall, xe buýt sẽ bốc người từ đó. Mật hiệu

di tản là

trên Đài Phát Thanh Quân Đội Mẽo là một mẩu tin thời tiết, “thời tiết

lúc này

là 105 độ và còn tăng”, tiếp theo là tám nốt nhạc, bài Giáng Sinh Trắng, Đừng

hỏi thằng ngu nào nghĩ

ra một mật hiệu như thế. Chẳng có gì là bí mật tại thành phố Sài Gòn

vào những

ngày như thế này, và bất cứ người Việt nào, ngay cả con chó của người

đó, cũng

biết, đây là một mật hiệu. Thirty

Years at 300

Millimeters by

Hubert Van Es Published

April 29, 2005 Copyright

2005 - The New York

Times Company PRINTED

WITH THE CONSENT OF

THE NEW YORK TIMES HONG KONG - Thirty years ago I was fortunate

enough to take a photograph that has become perhaps the most

recognizable image

of the fall of It was Tuesday, April 29, 1975. Rumors about

the final evacuation of Saigon had been rife for weeks, with thousands

of

people -- American civilians, Vietnamese citizens and third-country

nationals

-- being loaded on transport planes at Tan Son Nhut air base, to be

flown to The assembly point was on Gia Long Street,

opposite the The

journalists who had

decided to leave went to the assembly point, each carrying only a small

carry-on bag, as instructed. But the Vietnamese seeing this exodus were

quick

to figure out what was happening, and dozens showed up to try to board

the

buses. It took quite a while for the vehicles to show -- they were

being driven

by fully armed Marines, who were not very familiar with I

wasn't on them. I had

decided, along with several colleagues at United Press International,

to stay

as long as possible. As a Dutch citizen, I was probably taking less of

a risk

than the others. They included our bureau chief, Al Dawson; Paul Vogle,

a

terrific reporter who spoke fluent Vietnamese; Leon Daniel, an affable

Southerner; and a freelancer working for U.P.I. named Chad Huntley. I

was the

only photographer left, but luckily we had a bunch of Vietnamese

stringers, who

kept bringing in pictures from all over the city. These guys were

remarkable.

They had turned down all offers to be evacuated and decided to see the

end of

the war that had overturned their lives. On the

way back from the

evacuation point, where I had gotten some great shots of a Marine

confronting a

Vietnamese mother and her little boy, I photographed many panicking

Vietnamese

in the streets burning papers that could identify them as having had

ties to

the Returning to the office, which was on the top floor of the rather grandly named Peninsula Hotel, I started processing, editing and printing my pictures from that morning, as well as the film from our stringers. Our regular darkroom technician had decided to return to the family farm in the countryside. Two more U.P.I. staffers, Bert Okuley and Ken Englade, were still at the bureau. They had decided to skip the morning evacuation and try their luck in the early evening at the United States Embassy, where big Chinook helicopters were lifting evacuees off the roof to waiting Navy ships off the coast. (Both made it out that evening.) If you

looked north from the

office balcony, toward the cathedral, about four blocks from us, on the

corner

of Tu Do and Gia Long, you could see a building called the Pittman

Apartments,

where we knew the C.I.A. station chief and many of his officers lived.

Several

weeks earlier the roof of the elevator shaft had been reinforced with

steel

plate so that it would be able to take the weight of a helicopter. A

makeshift

wooden ladder now ran from the lower roof to the top of the shaft.

Around 2:30

in the afternoon, while I was working in the darkroom, I suddenly heard

Bert

Okuley shout, ''Van Es, get out here, there's a chopper on that roof!'' I grabbed my camera and the longest lens left

in the office -- it was only 300 millimeters, but it would have to do

-- and

dashed to the balcony. Looking at the Pittman Apartments, I could see

20 or 30

people on the roof, climbing the ladder to an Air America Huey

helicopter. At

the top of the ladder stood an American in civilian clothes, pulling

people up

and shoving them inside. Of course, there was no possibility that all

the people on the roof could get into the helicopter, and it took off

with 12

or 14 on board. (The recommended maximum for that model was eight.)

Those left

on the roof waited for hours, hoping for more helicopters to arrive. To

no

avail. After

shooting about 10

frames, I went back to the darkroom to process the film and get a print

ready

for the regular 5 p.m. transmission to And

this is where the

confusion began. For the caption, I wrote very clearly that the

helicopter was

taking evacuees off the roof of a downtown Later

that afternoon, five

Vietnamese civilians came into my office looking distraught and afraid.

They

had been on the Pittman roof when the chopper had landed, but were

unable to

get a seat. They asked for our help in getting out; they had worked in

the

offices of the United States Agency for International Development, and

were

afraid that this connection might harm them when the city fell to the

Communists. One of them had a two-way radio that could

connect to the embassy, and Chad Huntley managed to reach somebody

there. He

asked for a helicopter to land on the roof of our hotel to pick them

up, but

was told it was impossible. Al Dawson put them up for the night,

because by

then a curfew was in place; we heard sporadic shooting in the streets,

as

looters ransacked buildings evacuated by the Americans. All through the

night

the big Chinooks landed and took off from the embassy, each accompanied

by two

Cobra gunships in case they took ground fire. After a restless night, our photo stringers

started coming back with film they had shot during the late afternoon

of the

29th and that morning -- the 30th. Nguyen Van Tam, our radio-photo

operator,

went back and forth between our bureau and the telegraph office to send

the

pictures out to the world. I printed the last batch around 11 a.m. and

put them

in order of importance for him to transmit. The last was a shot of the

six-story chancery, next to the embassy, burning after being looted

during the

night. About 12:15 Mr. Tam called me and with a

trembling voice told me that that North Vietnamese troops were

downstairs at

the radio office. I told him to keep transmitting until they pulled the

plug,

which they did some five minutes later. The last photo sent from The war was over. I went out into the streets to photograph the

self-proclaimed liberators. We had been assured by the North Vietnamese

delegates, who had been giving Saturday morning briefings to the

foreign press

out at the airport, that their troops had been told to expect

foreigners with

cameras and not to harm them. But just to make sure they wouldn't take

me for

an American, I wore, on my camouflage hat, a small plastic Dutch flag

printed

with the words ''Boa Chi Hoa Lan'' (''Dutch Press''). The soldiers,

most of

them quite young, were remarkably friendly and happy to pose for

pictures. It

was a weird feeling to come face to face with the ''enemy,'' and I

imagine that

was how they felt too. I left Saigon on June 1, by plane for It was 15 years before I returned. My absence

was not for a lack of desire, but for the repeated rejections of my

visa

applications by an official at the press department of the Foreign

Ministry. It

turned out that I had a history with this man; he had come to our

office about

a week after Saigon fell because, as the editor of one of He obviously had a long memory, and I assume

it was only after he retired or died that my actions were forgiven and

I was

given a visa. I have since returned many times from my home in Hong

Kong,

including for the 20th and 25th anniversaries of the fall, at which

many old © Hubert Van Es Discuss

Thirty Years at 300

Millimeters in the forums Hubert Van Es, a freelance photographer,

covered the Vietnam War, the Moro Rebellion in the |