|

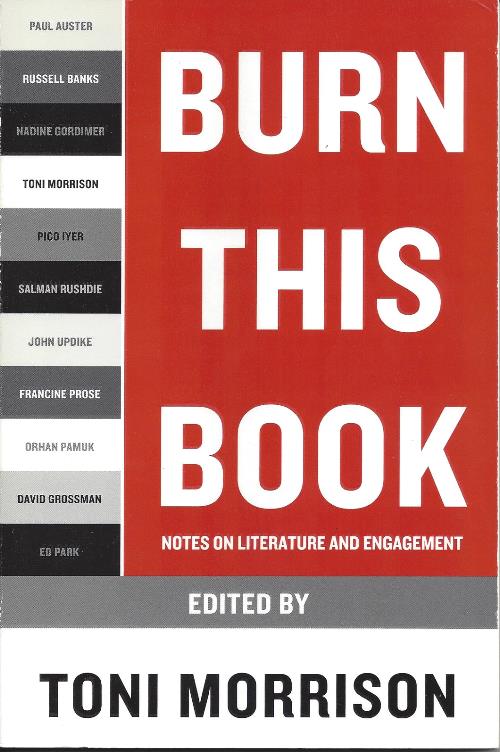

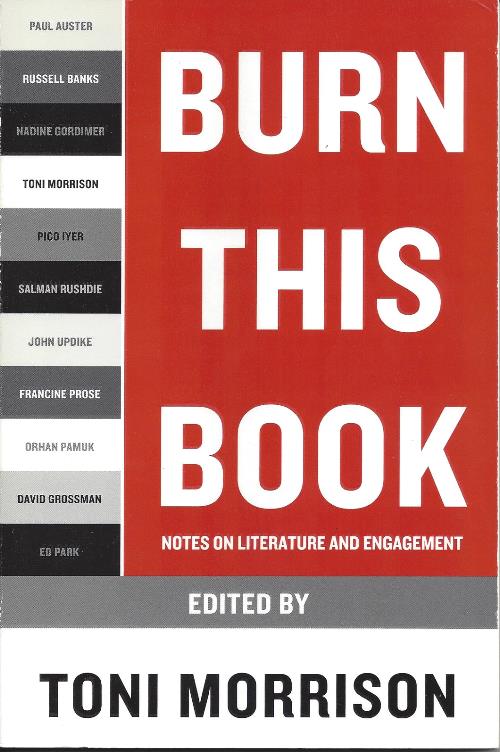

Tự Do Viết

Hãy đốt cuốn

sách này

A writer's life and work

are not a gift to mankind;

they are its necessity.

Toni Morrison

Cuộc đời và tác phẩm của

một nhà văn đếch phải là một món quà cho nhân

loại. Chúng là sự cần thiết của nó.

Tuyệt cú mèo!

Tự Do Viết

Đọc tại PEN cùng dịp với

DTH.

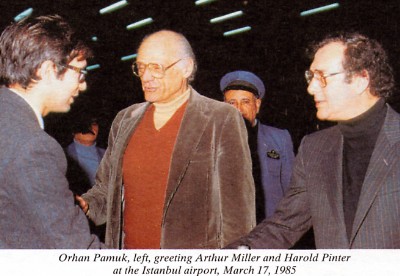

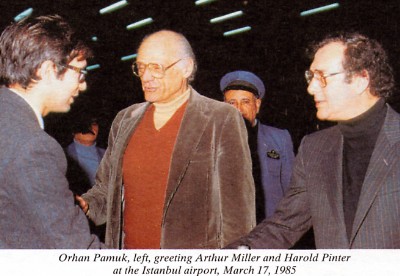

Vào Tháng Ba

1985, Arthur Miller và Harold Pinter ghé Istanbul. Vào lúc đó, hai đấng

này có

lẽ là hai khuôn mặt nổi cộm nhất trong giới kịch nghệ trên thế giới,

nhưng chán

mớ đời, không phải vì kịch cọt mà ông ghé Istanbul, mà vì những bóp

nghẹt tàn

nhẫn tự do ăn nói, viết lách, diễn đạt tư tưởng, ý nghĩ… vào thời gian

đó, và

vì rất nhiều nhà văn đang bị nhà nước bắt bỏ tù. Vào năm 1980 có 1 cú

đảo chánh

ở Thổ, và hàng ngàn người bị bắt, và tất nhiên, luôn luôn là giới cầm

viết bị

chiếu cố nặng nề nhất…. Hai đấng trên, đến Istanbul, là để gặp họ, gia

đình họ

để an ủi, động viên, trợ giúp, và bố cáo thế giới về số phận của họ.

Chuyến đi

của họ là do PEN sắp xếp cùng với Uỷ Ban Helsinki Watch Committee. Tôi

tới phi

trường để đón họ. Tôi được đề nghị cái job trên, không phải vì tôi rất

ư là sốt

sắng, rất thích đâm sầm vào chính trị, mà bởi vì tôi là 1 tiểu thuyết

gia nói

trơn tru tiếng Anh, và tôi hoan hỉ chấp nhận, cũng không hẳn là do, đó

là 1

cách để có tí đóng góp trong nghĩa cả, tức giúp đỡ những bạn đang trong

cơn khốn

khó, nhưng như thế có nghĩa là, sẽ được trải qua vài ngày sánh vai dạo

bước với

hai đấng nổi tiếng!

Chúng tôi

cùng nhau đi thăm những nhà xb nhỏ đang phải vật lộn, những văn phòng

bề bộn

nơi làm tin, newsrooms, những trung tâm, khu vực âm

u, bụi bặm, của những tạp chí đang trên đà

sập tiệm, chúng tôi đi từ nhà này sang nhà nọ, tiệm ăn này qua tiệm ăn

khác, để

gặp những nhà văn đang gặp rắc rối, và gia đình của họ.

Cho tới khi

đó, tôi còn đứng bên lề của thế giới chính trị, chẳng bao giờ tiến vô,

ngoại trừ

ép buộc, nhưng bây giờ, khi tai tôi nghe những câu chuyện nghẹt thở,

gây sốc, của

bách hại, của tàn nhẫn, độc ác, và cái ác trần trụi, toang hoác, tôi

cảm thấy

mình bị cuốn vô nó, qua cái cảm giác cảm thấy mình có lỗi, phạm tội –

không chỉ

bị cuốn hút vào nó, qua mặc cảm phạm tội, nhưng mà còn qua liên đới

trách nhiệm,

qua tinh thần đoàn kết, nhưng cùng 1 lúc, tôi cảm thấy ước muốn, cũng

bằng như

thế, nhưng ngược lại: tự bảo vệ mình, khỏi tất cả những điều này, và

chẳng làm

bất cứ điều gì trên đời, ngoài việc, viết ra những cuốn tiểu thuyết

thần sầu,

tuyệt đẹp.

Khi tôi đưa Miller và

Pinter bằng tắc xi từ điểm

hẹn này tới điểm hẹn khác, qua đường xá, xe cộ Istanbul, tôi nhớ lại,

như thế nào

chúng tôi lèm bèm về những người bán hàng rong, street vendors, những

chiếc xe

ngựa, những tấm quảng cáo, những người phụ nữ mang khăn choàng, hay

không mang

khăn choàng luôn quyến rũ cái nhìn của của những khách ngoại quốc, tuy

nhiên tôi

thật nhớ rõ một hình ảnh: tại cuối một hành lang thật dài của khách sạn

Istanbul Hilton, tôi và bạn tôi [người cùng tôi đón tiếp hai vị khách

quí] thì thầm vào tai nhau, trong 1 trạng

thái rất kích

động, thì cũng khi đó, Miller và Pinter cũng đang thì thầm ở cuối đầu

hành lang

kia, trong bóng tối, và cũng bằng 1 sự kích động u tối.

Hình ảnh này đóng khằn

vào cái đầu đang xốn xang của tôi, và tôi nghĩ, đây là hình ảnh nói lên

khoảng cách lớn lao giữa những câu chuyện, những lịch sử đầy rắc rối đa

đoan của

chúng tôi, và của họ, nhưng cùng lúc, nó cũng nói lên sự liên đới trách

nhiệm, sự

đoàn kết giữa những nhà văn, và đây là 1 điều có thể thực hiện được.

Freedom to Write

By Orhan Pamuk, Translated by Maureen

Freely

The following was given on April 25 as

the inaugural PEN

Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Memorial Lecture.

In March 1985 Arthur Miller and Harold Pinter made a trip

together to Istanbul.

At the time, they were perhaps the two most important names in world

theater,

but unfortunately, it was not a play or a literary event that brought

them to Istanbul, but the ruthless

limits being set on freedom of

expression in Turkey

at that time, and the many writers languishing in prison. In 1980 there

was a

coup in Turkey,

and hundreds of thousands of people were thrown into prison, and as

always, it

was writers who were persecuted most vigorously. Whenever I've looked

through

the newspaper archives and the almanacs of that time to remind myself

what it

was like in those days, I soon come across the image that defines that

era for

most of us: men sitting in a courtroom, flanked by gendarmes, their

heads

shaven, frowning as their case proceeds.... There were many writers

among them,

and Miller and Pinter had come to Istanbul

to meet with them and their families, to offer them assistance, and to

bring

their plight to the attention of the world. Their trip had been

arranged by PEN

in conjunction with the Helsinki Watch Committee. I went to the airport

to meet

them, because a friend of mine and I were to be their guides.

I had been proposed for this job not

because I had anything to

do with politics in those days, but because I was a novelist who was

fluent in

English, and I'd happily accepted, not just because it was a way of

helping

writer friends in trouble, but because it meant spending a few days in

the

company of two great writers. Together we visited small and struggling

publishing houses, cluttered newsrooms, and the dark and dusty

headquarters of

small magazines that were on the verge of shutting down; we went from

house to

house, and restaurant to restaurant, to meet with writers in trouble

and their

families. Until then I had stood on the margins of the political world,

never

entering unless coerced, but now, as I listened to suffocating tales of

repression, cruelty, and outright evil, I felt drawn to this world

through guilt—

drawn to it, too, by feelings of solidarity, but at the same time I

felt an

equal and opposite desire to protect myself from all this, and to do

nothing in

life but write beautiful novels. As we took Miller and Pinter by taxi

from

appointment to appointment through the Istanbul

traffic, I remember how we discussed the street vendors, the horse

carts, the

cinema posters, and the scarfless and scarf-wearing women that are

always so

interesting to Western observers. But I clearly remember one image: at

one end

of a very long corridor in the Istanbul Hilton, my friend and I are

whispering

to each other with some agitation, while at the other end, Miller and

Pinter

are whispering in the shadows with the same dark intensity. This image

remained

engraved in my troubled mind, I think, because it illustrated the great

distance between our complicated histories and theirs, while suggesting

at the

same time that a consoling solidarity among writers was possible.

I felt the same sense

of mutual pride and shared shame in every

other meeting we attended—room after room of troubled and chain-smoking

men. I

knew this because sometimes it was expressed openly, and sometimes I

felt it

myself or sensed it in other people's gestures and expressions. The

writers,

thinkers, and journalists with whom we were meeting mostly defined

themselves

as leftists in those days, so it could be said that their troubles had

much to

do with the freedoms held dear by Western liberal democracies. Twenty

years on,

when I see that half of these people—or thereabouts, I don't have the

precise

numbers—now align themselves with a nationalism that is at odds with

Westernization and democracy, I of course feel sad.

My experience as a

guide, and other like experiences in

later years, taught me something that we all know but that I would like

to take

this opportunity to emphasize. Whatever the country, freedom of thought

and

expression are universal human rights. These freedoms, which modern

people long

for as much as bread and water, should never be limited by using

nationalist

sentiment, moral sensitivities, or— worst of all—business or military

interests. If many nations outside the West suffer poverty in shame, it

is not

because they have freedom of expression but because they don't. As for

those

who emigrate from these poor countries to the West or the North to

escape

economic hardship and brutal repression—as we know, they sometimes find

themselves further brutalized by the racism they encounter in rich

countries.

Yes, we must also be alert to those who denigrate immigrants and

minorities for

their religion, their ethnic roots, or the oppression that the

governments of

the countries they've left behind have visited on their own people.

But to respect the

humanity and religious beliefs of

minorities is not to suggest that we should limit freedom of thought on

their

behalf. Respect for the rights of religious or ethnic minorities should

never

be an excuse to violate freedom of speech. We writers should never

hesitate on

this matter, no matter how "provocative" the pretext. Some of us have

a better understanding of the West, some of us have more affection for

those

who live in the East, and some, like me, try to keep our hearts open to

both

sides of this slightly artificial divide, but our natural attachments

and our

desire to understand those unlike us should never stand in the way of

our

respect for human rights.

I always have

difficulty expressing my political judgments

in a clear, emphatic, and strong way—I feel pretentious, as if I'm

saying

things that are not quite true. This is because I know I cannot reduce

my

thoughts about life to the music of a single voice and a single point

of view—I

am, after all, a novelist, the kind of novelist who makes it his

business to

identify with all of his characters, especially the bad ones. Living as

I do in

a world where, in a very short time, someone who has been a victim of

tyranny

and oppression can suddenly become one of the oppressors, I know also

that

holding strong beliefs about the nature of things and people is itself

a

difficult enterprise. I do also believe that most of us entertain these

contradictory thoughts simultaneously, in a spirit of good will and

with the

best of intentions. The pleasure of writing novels comes from exploring

this

peculiarly modern condition whereby people are forever contradicting

their own

minds. It is because our modern minds are so slippery that freedom of

expression becomes so important: we need it to understand ourselves,

our shady,

contradictory, inner thoughts, and the pride and shame that I mentioned

earlier.

So let me tell another story that

might cast some light on

the shame and pride I felt twenty years ago while I was taking Miller

and Pinter

around Istanbul.

In the ten years following their visit, a series of coincidences fed by

good

intentions, anger, guilt, and personal animosities led to my making a

series of

public statements on freedom of expression that bore no relation to my

novels, and

before long I had taken on a political persona far more powerful than I

had

ever intended. It was at about this time that the Indian author of a

United

Nations report on freedom of expression in my part of the world—an

elderly

gentleman—came to Istanbul

and looked me up. As it happened, we, too, met at the Hilton Hotel. No

sooner

had we sat down at a table than the Indian gentleman asked me a

question that

still echoes strangely in my mind: "Mr. Pamuk, what is there going on

in

your country that you would like to explore in your novels but shy away

from,

due to legal prohibitions?"

There followed a long silence. Thrown

by his question, I

thought and thought and thought. I plunged into an anguished

Dostoevskyan

self-interrogation. Clearly, what the gentleman from the UN wished to

ask was,

"Given your country's taboos, legal prohibitions, and oppressive

policies,

what is going unsaid?" But because he had—out of a desire to be polite,

perhaps?—asked the eager young writer sitting across from him to

consider the

question in terms of his own novels, I, in my inexperience, took his

question

literally. In the Turkey

of ten years ago, there were many more subjects kept closed by laws and

oppressive state policies than there are today, but as I went through

them one

by one, I could find none that I wished to explore "in my novels."

But I knew, nonetheless, that if I said "there is nothing I wish to

write

in my novels that I am not able to discuss," I'd be giving the wrong

impression. For I'd already begun to speak often and openly about all

these

dangerous subjects outside my novels. Moreover, didn't I often and

angrily

fantasize about raising these subjects in my novels, just because they

happened

to be forbidden? As I thought all this through, I was at once ashamed

of my

silence, and reconfirmed in my belief that freedom of expression has

its roots

in pride, and is, in essence, an expression of human dignity.

I have personally known writers who

have chosen to raise

forbidden topics purely because they were forbidden. I think I am no

different.

Because when another writer in another house is not free, no writer is

free.

This, indeed, is the spirit that informs the solidarity felt by PEN, by

writers

all over the world.

Sometimes my friends

rightly tell me or someone else,

"You shouldn't have put it quite like that; if only you had worded it

like

this, in a way that no one would find offensive, you wouldn't be in so

much

trouble now." But to change one's words and package them in a way that

will be acceptable to everyone in a repressed culture, and to become

skilled in

this arena, is a bit like smuggling forbidden goods through customs,

and as

such, it is shaming and degrading.

The theme of this

year's PEN festival is reason and belief.

I have related all these stories to illustrate a single truth —that the

joy of

freely saying whatever we want to say is inextricably linked with human

dignity. So let us now ask ourselves how "reasonable" it is to

denigrate cultures and religions, or, more to the point, to mercilessly

bomb

countries, in the name of democracy and freedom of thought. My part of

the

world is not more democratic after all these killings. In the war

against Iraq,

the

tyrannization and heartless murder of almost a hundred thousand people

has

brought neither peace nor democracy. To the contrary, it has served to

ignite

national-ist, anti-Western anger. Things have become a great deal more

difficult for the small minority who are struggling for democracy and

secularism in the Middle East. This

savage,

cruel war is the shame of America

and the West. Organizations like PEN and writers like Harold Pinter and

Arthur

Miller are its pride.

Copyright © 2006 by

Ohan Pamuk; English translation

copyright © 2006 by Maureen Freely.

|