|

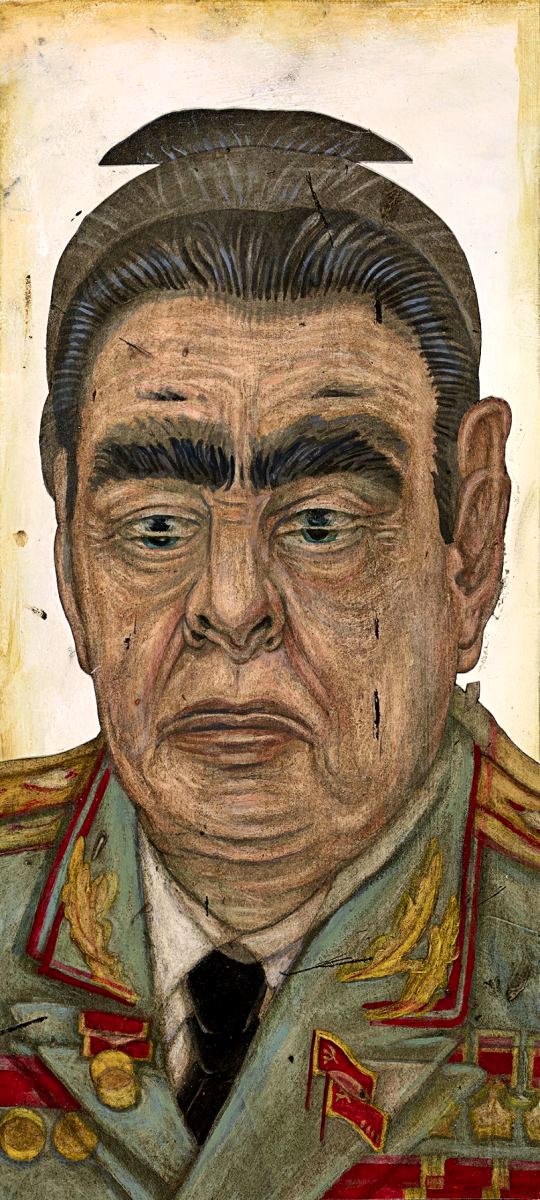

Brezhnev Bus Stop By

Tatyana Tolstaya Brezhnev

died on November 10, 1982, just a few days

after I was operated on at Dr. Fyodorov’s famous eye clinic. I was

nearsighted,

and Fyodorov and his doctors, it was said, could correct your vision.

They made

incisions in the cornea, so that it splayed open and then healed closer

to the

lens, where the rays of light focus. (Imagine that you bought a beret

that was

too small, then made slits along the radius and inserted wedges so that

it

would fit your head.) They made the cuts with a Neva razor; they

weren’t using

lasers yet in 1982. The

doctor’s art consisted of making these incisions

at the correct depth, so that, when the eyes healed, your vision would

be

20/20. You would be able to read not just the big letters at the top of

the

chart but the tiny ones at the very bottom as well. However, for the

three

months it took to heal you’d have aches and sharp pains, and produce

abundant

tears in the presence of even the slightest light. Nighttime was

easier, but

the color green, for some reason, was torture. Traffic-light green. The

excruciating pain lasted a week; after that, the flame under the frying

pan was

turned down, and the sauce just simmered, flaring up occasionally as

chili

peppers were added. First,

they operated on one eye, and then, a week or

so later, on the other. My first operation must have been on November

5th. It

couldn’t have been on November 7th—the Revolutionary holiday—or on

November 8th

or 9th, because it’s a well-known fact that after holidays doctors’

hands

tremble. And November 6th was a short workday, because, well, everyone

needed

time to stand in line, in case the stores happened to have something

that was

usually in short supply. I

had the operation, and then for two days the whole

country ate potato salad with mayonnaise, fish in sour cream, and

homemade

cookies, called “nuts,” that were filled with boiled condensed milk.

Then there

was the hangover, low skies, occasional snow flurries, sluggishness,

and, as

always . . . But, no, not at all as always! Brezhnev died! Unbelievable! We

had thought that Brezhnev was eternal. Not

because he was good or bad or because he understood things or was truly

as

dense as a sack of Party potatoes, as he was in the jokes told about

him:

“Comrade Brezhnev, Christ is risen!” “Thank you, I’ve already been

informed.”

He simply was. He hung over the land like a thick cloud, from which

rain lashed

out or snow fell in heaps. Then, suddenly, the climate changed. But to

what, no

one could say. Once

the holidays were over, the pastries had all

been eaten, and the tremor in surgeons’ hands had abated, the day to

remove my

bandage and operate on the other eye arrived—November 15th. I took the

metro to

the end of the line, and then travelled by bus to Fyodorov’s clinic, in

Beskudnikovo. The bus slowly made its way across railroad tracks, past

beer

stands with long lines, alongside mountains of crushed rock and garbage

dumps,

through far-flung villages slated for demolition. Angry snowflakes came

spinning down from the gloomy sky as I looked blurrily out the window

with one

eye. Brezhnev

had died on the tenth, and now, after four days

of official mourning, he would be buried. Five minutes of silence were

to be

observed as he was lowered into the ground. The whole country stopped

for five

minutes, and the bus that was carrying me stopped, too—right on the

train

tracks that it was crossing. We were almost at the eye clinic, but the

driver

turned off the engine. It grew quiet and cold. I looked around. There

were ten

or so people on the bus, all of them patients of the clinic, each with

a

bandaged eye. I

could sense, physically, the rage that was growing

around me. Ten half-blind Soviet people sat in a bus as cold as the

grave,

while snow whirled and beat against the windows. Ten Cyclopes kept

their single

eyes lowered, so as not to betray any emotion, but the position of the

mouth and

the lines in the forehead can be more eloquent than words or eyes. By

the time

the five minutes were up, we were all exhaling vapor; the air in the

bus was

freezing. Then

the motor turned over, revved, and a weak

stream of warm air began to flow. Thus we bade farewell to an era.  Yiyun Li: Lắng nghe là Tin

tưởng

Tờ The New

Yorker có mục “Thế Giới Nội”, dành cho đám nhà văn mũi lõ tập tành viết

Tạp Ghi

như… GCC.

|