|

GNV tính thu

gom ba bài viết có tính kỷ niệm, hồi ký, chuyện nghề... vô đây, thong

thả sẽ

edit, thành 1 cuốn kiểu như của mấy tay VC Nguyễn Khải, Tô Hoài... “Đi

tìm cái

ác đã mất”! Site của anh

là một trong những site mà người viết thư này hay vào. Tuy không quen,

không biết

anh, người viết cũng đánh bạo mà xin anh cho vài câu trả lời dùm : Làm

cách nào

mà anh đọc nhiều, viết thật nhiều, maintain cái site của anh, giữ mối

liên lạc

bằng hữu và người thân, mà không thức trắng đêm, ngày này sang ngày

khác vậy

??? K Nhân đọc 1

bài viết trên tờ Books, GCC

kiếm thấy câu trả lời: Sớm hay muộn,

tất cả những tay như GCC, sau cùng, đều giống nhau. Chúng không ngừng

làm việc,

chẳng để mất 1 phút. Thật là tởm! V S Pritchett Bài trên Books, dịch từ 1

bài tiếng Anh, trên Literary

Review. Christopher

Hart Erik Satie

may have worn chestnut-coloured velvet suits, eaten thirty-egg

omelettes and

founded the Church of Jesus Christ the Conductor, but this was just

bohemian

decoration. He also walked 12 miles into and out of Paris every day,

composing

all the way. In his introduction to this wonderfully entertaining

little book,

Mason Currey quotes V S Pritchett: 'Sooner or later, the great men turn

out to

be all alike. They never stop working. They never lose a minute. It is

very

depressing.' It should

come as no surprise, perhaps, that most high-achieving creative people

who have

given something permanent to the world are not really in the slightest

bit

bohemian. They discover for themselves Flaubert's famous advice that

one should

live like a bourgeois and put one's bohemianism into one's work.Food is

often

of little importance, mere brain fuel. Patricia Highsmith lived on

vodka,

cereal and bacon and eggs. For lunch Ingmar Bergman ate a revolting

sort of

baby food made up of yoghurt and strawberry jam which he mixed in with

cornflakes.

In the evening he enjoyed watching Dallas. Few strike

you as being terribly busy or working long hours, though poor Mozart is

one.

His daily routine in Vienna in his twenties was: hair done by 6am;

dressed by

7; composing until 9. From 9 to 1 he gave lessons. Then lunch. In the

afternoon

he would either give a concert or carry on composing until 9pm. Then a

visit to

dear Stanze, home at 11, a little more composing and finally to bed at

1. Five

hours' sleep and then the whole routine again. Beethoven

had it easier. Up at dawn, coffee (with exactly sixty beans to each

cup), then

work. A light lunch, walking all afternoon and, in the evening, dinner

out,

theatre or a quiet supper at home. Bed by 10pm at the latest. This

essential

routine of working all morning, walking all afternoon, recurs in the

lives of

other creatives. Benjamin Britten was the same and Mahler too, though

his poor

wife, Alma, had to look after him, lamenting, 'I've sunk to the level

of

housekeeper!' The best

inspiration often came while walking. Beethoven always took a pencil

and paper

with him in the Vienna Woods, and Kierkegaard often came home and

started

scribbling again still in his hat and coat. Some always wrote standing

up -

Hemingway and, I think, Virginia Woolf (who is not covered here).

Nabokov

started standing up, then progressed to sitting and finally lying down.

Few

seem to have practised any more violent exercise than walking, apart

from Byron

with his boxing and riding and, rather surprisingly, Joan Miró. The

dreamy surrealist

was an ardent practitioner of boxing, running and 'Mediterranean yoga'.

He

detested going to parties, telling an American journalist, 'They get on

my

tits.' A key

component of genius is sheer energy, and that requires health and

self-discipline. Haruki Murakami writes in the morning, runs or swims

(or does

both) in the afternoon and is in bed by 9pm every day. He observes,

'Physical

strength is as necessary as artistic sensitivity.' Bohos on

self-destruct might

write a few exquisite fleurs du mal, but they are rare. For

stimulants, again and again, it's just tea and coffee, rarely alcohol,

let

alone anything else. Balzac drank fifty cups of coffee a day and so did

Voltaire. The latter's doctor warned him that it was a slow poison, at

which

Voltaire quipped that it must be, since he'd been drinking it for

seventy

years. He also liked to work in bed, as did Descartes, who hated rising

early.

Unfortunately he took a job teaching philosophy to Queen Christina of

Sweden,

was commanded to be ready to start her lessons at 5am and was dead of

pneumonia

within weeks. Thomas Mann

evidently loved his kip, rising at 8am, enjoying a good hour's nap in

the

afternoon and going to bed around midnight, in a separate bedroom from

his

wife. Richard Strauss appears to have slept a good ten hours a night.

The

results of all this bourgeois self-discipline and these early nights

are plain:

many of those who followed such a regimen were hugely prolific as well

as

great, from Bach to Balzac to Dickens. F Scott Fitzgerald, I was

astonished to

learn, sometimes wrote up to eight thousand words a day. This is

approaching

Barbara Cartland levels, but it didn't seem to do his prose much harm. Proust,

unusually, slept all day and wrote all night, lying in bed propped up

on one

elbow, by the light of one weak, green-shaded lamp. It sounds like a

recipe for

backache, eyestrain and misery, and he wrote, 'After ten pages I am

shattered.'

Should he have gone for a good walk, even with his asthma? Dr Johnson

was also

a nocturnal writer, as was Kafka, by necessity rather than choice, and

Flaubert. He began writing only at 9pm, spending the earlier part of

the day

lunching, dining, strolling, sitting, reading or applying a tonic to

his head

that was supposed to stop him going bald. He was pleased to manage two

pages a

week. (It would of course be unpardonably philistine to suggest that

this was

because of the time of day he chose to write, rather than because he

was

painstakingly crafting the most pristine prose style in modern

literature.) And

there is only one figure here who seems to have worked in the

afternoon: James

Joyce, while writing Ulysses. Daily

Rituals is a thoroughly researched, minutely annotated and delightful

little

book, full of the quirks and oddities of the human comedy. How striking

that

both Milton and Richard Strauss, quite independently, compared their

creativity

to a cow being milked. Its main lesson can be summed up simply enough:

get up,

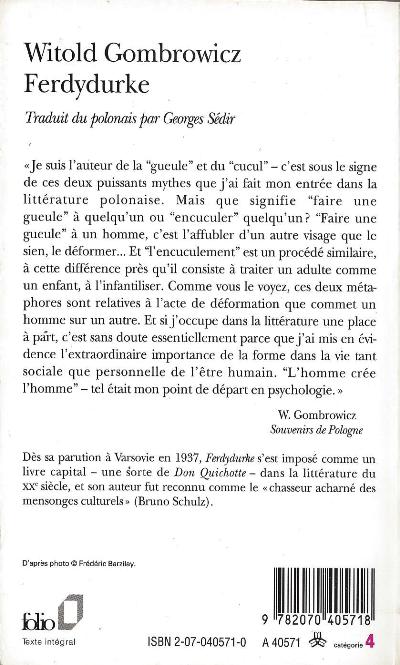

have a cup of coffee, sit at your desk and begin.  Trên tờ TLS

số 4 April, 2014 có bài điểm cuốn “Nhật Ký” của WG. Người điểm gọi, một

đại tác

phẩm.

|