|

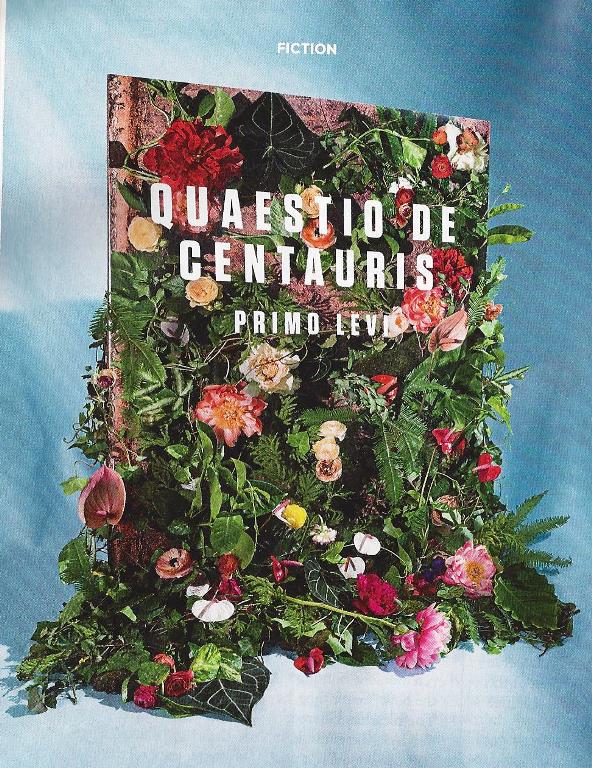

Fiction June

8, 2015 Issue By Primo

Levi My father

kept him in a stall, because he didn’t know where else to keep him. He

had been

given to my father by a friend, a sea captain, who said that he had

bought him

in Salonika; however, I learned from him directly that he was born in

Colophon. I had been

strictly forbidden to go anywhere near him, because, I was told, he was

easily

angered and would kick. But from my personal experience I can confirm

that this

was an old superstition, and from the time I was an adolescent I never

paid

much attention to the prohibition and in fact spent many memorable

hours with

him, especially in winter, and wonderful times in summer, too, when

Trachi

(that was his name) with his own hands put me on his back and took off

at a mad

gallop toward the woods on the hills. He had

learned our language fairly easily, but retained a slight Levantine

accent.

Despite his two hundred and sixty years, his appearance was youthful,

in both

his human and his equine aspects. What I will relate here is the fruit

of our

long conversations. The

centaurs’ origins are legendary, but the legends that they pass down

among

themselves are very different from the classical tales we know. Remarkably,

their traditions also refer to a Noah-like inventor and savior, a

highly

intelligent man they call Cutnofeset. But there were no centaurs on

Cutnofeset’s ark. Nor, by the way, were there “seven pairs of every

species of

clean beast, and a pair of every species of the beasts that are not

clean.” The

centaurian tradition is more rational than the Biblical, holding that

only the

archetypal animals, the key species, were saved: man but not the

monkey; the

horse but not the donkey or the wild ass; the rooster and the crow but

not the

vulture or the hoopoe or the gyrfalcon. How, then,

did these species come about? Immediately afterward, the legend says.

When the

waters retreated, a deep layer of warm mud covered the earth. Now, this

mud,

which harbored in its decay all the enzymes from what had perished in

the

flood, was extraordinarily fertile: as soon as it was touched by the

sun, it

was covered with shoots from which grasses and plants of every type

sprang

forth; and, further, its soft, moist bosom was host to the marriages of

all the

species saved in the ark. It was a time, never to be repeated, of wild,

ecstatic fecundity, in which the entire universe felt love, so

intensely that

it nearly returned to chaos. Those were

the days when the earth itself fornicated with the sky, when everything

germinated and everything was fruitful. Not only every marriage but

every

union, every contact, every encounter, even fleeting, even between

different

species, even between beasts and stones, even between plants and

stones, was

fertile, and produced offspring not in a few months but in a few days.

The sea

of warm mud, which concealed the earth’s cold, prudish face, was one

boundless

nuptial bed, all its recesses boiling over with desire and teeming with

jubilant germs. This second

creation was the true creation, because, according to what is passed

down among

the centaurs, there is no other way to explain certain similarities,

certain

convergences observed by all. Why is the dolphin similar to the fish,

and yet

gives birth and nurses its offspring? Because it’s the child of a tuna

and a

cow. Where do butterflies get their delicate colors and their ability

to fly?

They are the children of a flower and a fly. Tortoises are the children

of a

frog and a rock. Bats of an owl and a mouse. Conchs of a snail and a

polished

pebble. Hippopotami of a horse and a river. Vultures of a worm and an

owl. And

the big whales, the leviathans—how to explain their immense mass? Their

wooden

bones, their black and oily skin, and their fiery breath are living

testimony

to a venerable union in which—even when the end of all flesh had been

decreed—that same primordial mud got greedy hold of the ark’s feminine

keel,

made of gopher wood and covered inside and out with shiny pitch. Such was the

origin of every form, whether living today or extinct: dragons and

chameleons,

chimeras and harpies, crocodiles and minotaurs, elephants and giants,

whose

petrified bones are still found today, to our amazement, in the heart

of the

mountains. And so it was for the centaurs themselves, since in this

festival of

origins, in this panspermia, the few survivors of the human family also

participated. Notably,

Cam, the profligate son, participated: the first generation of centaurs

originated in his wild passion for a Thessalian horse. From the

beginning,

these progeny were noble and strong, preserving the best of both equine

and

human nature. They were at once wise and courageous, generous and

shrewd, good

at hunting and at singing, at waging war and at observing the heavens.

It

seemed, in fact, as happens with the most felicitous unions, that the

virtues

of the parents were magnified in their offspring, since, at least in

the

beginning, they were more powerful and faster racers than their

Thessalian

mothers, and a good deal wiser and more cunning than black Cam and

their other

human fathers. This would also explain, according to some, their

longevity,

though others have attributed it to their eating habits, which I will

come to

in a moment. Or their longevity could simply be a projection across

time of

their great vitality, and this I, too, believe resolutely (and the

story I am

about to tell attests to it): that in hereditary terms the herbivore

power of

the horse counts less than the red blindness of the bloody and

forbidden spasm,

the moment of human-feral fullness in which the centaurs were conceived. Whatever we

may think of this, anyone who has carefully considered the centaurs’

classical

traditions cannot help noticing that centauresses are never mentioned.

As I

learned from Trachi, they do not in fact exist. The man-mare

union, very seldom fertile today, produces and has produced only male

centaurs,

for which there must be a fundamental reason, though at present it

eludes us.

As for the inverse, the union between stallions and women, this has

scarcely

ever occurred, and comes about through the solicitation of dissolute

women, who

by nature are not particularly inclined to procreate. In the

exceptional cases in which fertilization is successful in these rare

unions, a

dualistic female offspring is produced, her two natures, however,

inversely

assembled. The creatures have the head, neck, and front feet of a

horse, but

their back and belly are those of a human female, and the hind legs are

human. During his long

life Trachi had encountered very few of them, and he assured me that he

felt no

attraction to these squalid monsters. They were not “proud and nimble”

but

insufficiently vital; they were infertile, idle, and transient; they

did not

become familiar with man or learn to obey his commands but lived

miserably in

the densest forests, not in herds but in rural solitude. They fed on

grass and

berries, and when they were surprised by a man they had the curious

habit of

always presenting themselves to him head first, as if embarrassed by

their

human half. Trachi was

born in Colophon of a secret union between a man and one of the

numerous

Thessalian horses that are still wild on the island. I am afraid that

among the

readers of these notes are some who may refuse to believe these

assertions,

since official science, permeated as it still is today with

Aristotelianism,

denies the possibility of a fertile union between different species.

But

official science often lacks humility: such unions are, indeed,

generally infertile,

but how often has evidence been sought? No more than a few dozen times.

And has

it been sought among all the innumerable possible couplings? Certainly

not.

Since I have no reason to doubt what Trachi has told me about himself,

I must

therefore encourage the incredulous to consider that there are more

things in

heaven and on earth than are dreamed of in our philosophy. He lived

mostly in solitude, left to himself, which was the common destiny of

those like

him. He slept in the open, standing on all four hooves, with his head

on his

arms, which he would lean against a low branch or a rock. He grazed in

the

island’s fields and glades, or gathered fruit from branches; on the

hottest

days he would go down to one of the deserted beaches, and there he

would bathe,

swimming like a horse, chest and head erect, and then he would gallop

for a

long while, violently churning up the wet sand. But the bulk

of his time, in every season, was devoted to food: in fact, during the

forays

that Trachi in the vigor of his youth frequently undertook among the

barren

cliffs and gorges of his native island, he always, following an

instinct for

prudence, brought along, tucked under his arms, two big bundles of

grass or

foliage, gathered in times of rest. Although

centaurs are limited to a strictly vegetarian diet by their

predominantly

equine constitution, it must be remembered that they have a torso and a

head

like a man’s, which obliges them to introduce through a small human

mouth the

considerable quantity of grass, straw, or grain necessary to sustain

their

large bodies. These foods, notably of limited nutritional value, also

require

long mastication, since human teeth are not well adapted to the

grinding of

forage. In

conclusion, the nourishment of centaurs is a laborious process; by

physical

necessity, they are required to spend three-quarters of their time

chewing.

This fact is not lacking in authoritative testimonials, first and

foremost that

of Ucalegon of Samos (Dig. Phil., XXIV, II–8 and XLIII passim), who

attributes

the centaurs’ proverbial wisdom to their alimentary regimen, which

consists of

one continuous meal from dawn to dusk: this deters them from other vain

or

baleful activities, such as gossip or the pursuit of riches, and

contributes to

their usual self-restraint. Bede also mentions this in his “Historia

Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum.” It is rather

strange that the classical mythological tradition neglects this

characteristic

of centaurs. The truth of it rests on reliable evidence, and, as we

have shown,

it can be deduced by a simple consideration of natural philosophy. To return to

Trachi: his education was, by our criteria, fragmentary. He learned

Greek from

the island’s shepherds, whose company he occasionally sought out,

despite his

shy and taciturn nature. From his own observations, he learned many

subtle and

intimate things about grasses, plants, forest animals, water, clouds,

stars,

and planets; I myself noticed that, even after his capture, and under a

foreign

sky, he could feel the approach of a gale or the imminence of a

snowstorm many

hours before it actually arrived. Though I couldn’t say how, nor could

he

himself, he also felt the grain growing in the fields, he felt the

pulse of

water in underground streams, and he sensed the erosion of flooded

rivers. When

De Simone’s cow gave birth two hundred metres away from us, he felt a

reflex in

his own gut; the same thing happened when the tenant farmer’s daughter

gave

birth. In fact, on a spring evening he informed me that a birth was

taking

place and, more precisely, in a particular corner of the hayloft; we

went there

and found that a bat had just brought into the world six blind little

monsters,

and was feeding them minuscule portions of her milk. All centaurs

are made this way, he told me, feeling every germination, animal,

human, or

vegetable, as a wave of joy running through their veins. They also

perceive, in

the precordial region, and in the form of anxiety and tremulous

tension, every

desire and every sexual encounter that occurs in their vicinity;

therefore,

even though they are usually chaste, they enter into a state of vivid

agitation

during the season of love. We lived

together for a long time: in some ways, I can say that we grew up

together.

Despite his advanced age, he was actually a young creature in

everything he

said and did, and he learned things so easily that it seemed pointless

(not to

mention awkward) to send him to school. I educated him myself, almost

inadvertently, passing on to him the knowledge that I learned from my

teachers. Cartoon “I’ve got

you on the waiting list, but I think it’s for a Birkin bag.” Buy the

print » We kept him

hidden as much as possible, partly because of his own explicit wish,

partly

because of a form of exclusive and jealous affection that we all felt

for him,

and partly because a combination of rationality and intuition advised

us to

shield him from unnecessary contact with our human world. Naturally,

word of his presence in our barn leaked out among the neighbors. At

first, they

asked a lot of questions, some rather intrusive, but then, as will

happen,

their curiosity diminished from lack of nourishment. A few of our

intimate

friends were allowed to see him, the first of whom were the De Simones,

and

they swiftly became his friends, too. Only once, when a horsefly bite

provoked

a painful abscess in his rump, did we require the skill of a

veterinarian, but

he was an understanding and discreet man, who most scrupulously

promised to

keep this professional secret and, as far as I know, kept his promise. Things went

differently with the blacksmith. Nowadays, blacksmiths are

unfortunately rather

scarce: we found one two hours away by foot, and he was a yokel, stupid

and

brutish. My father tried in vain to persuade him to maintain a certain

reserve,

in part by paying him tenfold for his services. It made no difference;

every

Sunday at the tavern he gathered a crowd around him and told the entire

village

about his strange client. Luckily, he liked his wine and was in the

habit of

telling tall tales when he was drunk, so he wasn’t taken too seriously. I find it

painful to write this story. It is a story from my youth, and I feel

that in

writing it I am expelling it from myself, and that later I will feel

bereft of

something strong and pure. One summer

Teresa De Simone, my childhood friend and cohort, returned to her

parents’

house. She had gone to the city to study, and I hadn’t seen her for

many years;

I found her changed, and the change troubled me. Maybe I had fallen in

love,

but with little consciousness of it: what I mean is, I did not admit it

to

myself, not even hypothetically. She was quite lovely, shy, calm, and

serene. As I’ve

already mentioned, the De Simones were among the few neighbors whom we

saw with

some regularity. They knew Trachi and loved him. After

Teresa’s return, we spent a long evening together, just the three of

us. It was

one of those unique, never-to-be-forgotten evenings: the moon, the

crickets,

the intense smell of hay, the air still and warm. We heard singing in

the

distance, and suddenly Trachi began to sing, without looking at us, as

if in a

dream. It was a long song, its rhythm bold and strong, with words I

didn’t

understand. A Greek song, Trachi said; but when we asked him to

translate it he

turned his head away and fell silent. We were all

silent for a long time; then Teresa went home. The following morning,

Trachi

drew me aside and said this: “Oh, my dearest friend, my hour has come.

I have

fallen in love. That woman has got inside of me, and possesses me. I

desire to

see her and hear her, perhaps even touch her, and nothing else; I

therefore

desire something impossible. I am reduced to one point: there is

nothing left

of me except this desire. I am changing, I have changed, I have become

another.” He told me

other things as well, which I hesitate to write, because it’s unlikely

that my

words will do him justice. He told me that, since the previous night,

he had

become “a battlefield”; that he understood, as he never had before, the

exploits of his violent ancestors, Nessus, Pholus; that his entire

human half

was crammed with dreams, with noble, courtly, and vain fantasies; that

he

wanted to accomplish reckless feats and fight for justice with the

strength of

his own arms, raze to the ground the densest forests with his

vehemence, run to

the ends of the earth, discover and conquer new lands, and create there

the

works of a fertile civilization. All of this, in a way that was obscure

even to

himself, he wanted to perform before the eyes of Teresa De Simone: to

do it for

her, to dedicate it to her. Finally, he told me, he realized the vanity

of his

dreams in the very act of dreaming them, and this was the content of

the song

of the previous evening, a song that he had learned long ago, during

his

adolescence in Colophon, and which he had never understood and never

sung until

now. For many

weeks, nothing else happened; we saw the De Simones every so often, but

Trachi’s behavior revealed nothing of the storm that raged inside him.

It was

I, and no one else, who provoked the breakdown. One October

evening, Trachi was at the blacksmith’s. I met Teresa, and we went for

a walk

together in the woods. We talked, and of whom but Trachi? I didn’t

betray my

friend’s confidence, but I did worse. I quickly

understood that Teresa was not as shy as she initially appeared to be:

she

chose, as if by chance, a narrow path that led into the thickest part

of the

woods; I knew it was a dead end, and knew that Teresa knew. Where the

path came

to an end, she sat down on dry leaves and I did the same. The valley

bell tower

rang out seven times, and she pressed up against me in a way that rid

me of all

doubt. By the time we got home, night had fallen, but Trachi hadn’t yet

returned. I

immediately realized that I had behaved badly; in fact, I realized it

during

the act itself, and still today it pains me. Yet I also know that the

fault was

not all mine, nor was it Teresa’s. Trachi was with us: we had immersed

ourselves in his aura, we had gravitated into his field. I know this

because I

myself had seen that wherever he passed flowers bloomed before their

time, and

their pollen flew in his wake as he ran. Trachi

didn’t return. Over the following days, we laboriously reconstructed

the rest

of his story based upon witnesses’ accounts and his tracks. After a

night of anxious waiting for all of us, and of secret torment for me, I

went to

look for him myself at the blacksmith’s. The blacksmith wasn’t at home:

he was

in the hospital with a cracked skull, and unable to speak. I found his

assistant. He told me that Trachi had come at about six o’clock to get

shoed. He

was silent and sad, but tranquil. Without showing any impatience, he

let

himself be chained as usual (the uncivilized practice of this

particular

blacksmith, who, years earlier, had had a bad experience with a

skittish horse;

we had tried, in vain, to convince him that this precaution was in

every way

absurd with regard to Trachi). Three of his hooves had already been

shoed when

a long and violent shudder coursed through him. The blacksmith turned

on him

with that harsh tone often used on horses; as Trachi’s agitation seemed

to

increase, the blacksmith struck him with a whip. Trachi

appeared to calm down, “but his eyes were rolling around as if he were

mad, and

he seemed to be hearing voices.” Suddenly, with a furious tug, he

pulled the

chains from their wall mounts, and the end of one hit the blacksmith in

the

head, sending him to the floor in a faint. Trachi then threw himself

against

the door with all his might, head first, arms crossed over his head,

and

galloped off toward the hills while the four chains, still constricting

his

legs, whirled around, wounding him repeatedly. “What time

did that happen?” I asked, with a disturbing presentiment. The

assistant hesitated: it was not yet night, but he couldn’t say

precisely. Well,

yes, now he remembered: just a few seconds before Trachi pulled the

chains from

the wall, the time had rung from the bell tower, and the boss had said

to him,

in dialect so that Trachi wouldn’t understand, “It’s already seven

o’clock! If

all my clients were as currish as this one . . .” Seven

o’clock! It wasn’t

difficult, unfortunately, to follow Trachi’s furious flight; even if no

one had

seen him, there were conspicuous traces of the blood he had lost, of

the

scrapes the chains had inflicted on tree trunks and rocks by the side

of the

road. He hadn’t headed toward home, or toward the De Simones’: he had

cleared

the two-metre wooden fence that surrounded the Chiapasso property, and

crossed

straight through the vineyards in a blind fury, knocking down stakes

and vines,

breaking the thick iron wires that supported the vine shoots. He reached

the barnyard and found the barn door bolted shut from the outside. He

could

have opened it easily with his hands; instead, he picked up an old

thresher,

weighing well over fifty kilos, and hurled it at the door, reducing it

to

splinters. Only six cows, a calf, some chickens and rabbits were in the

barn.

Trachi left immediately and, still at a mad gallop, headed toward Baron

Caglieris’s estate. It was at

least six and a half kilometres away, on the other side of the valley,

but

Trachi got there in a matter of minutes. He looked for the stable: he

found it

not with his first blow but only after he had used his hooves and

shoulders to

knock down several doors. What he did in the stable we know from an

eyewitness,

a stableboy, who, at the sound of the door shattering, had had the good

sense

to hide in the hay and from there had seen everything. Trachi

hesitated for a moment on the threshold, panting and bloody. The

horses,

unsettled, tossed their heads, tugging on their halters. Trachi pounced

on a

three-year-old white mare; in one stroke he severed the chain that

bound her to

the trough, and dragging her by that chain led her outside. The mare

didn’t put

up any resistance, which was strange, the stableboy told me, since she

had a

rather skittish and reluctant character, and was not in heat. They

galloped together as far as the river: here Trachi was seen to stop,

cup his

hands, dip them into the water, and drink repeatedly. They then

proceeded side

by side into the woods. Yes, I followed their tracks: into those same

woods,

along that same path, to that same place where Teresa had asked me to

take her. And it was

right there, for that entire night, that Trachi must have celebrated

his

monstrous nuptials. I found the ground dug up, broken branches, brown

and white

horsehair, human hair, and more blood. Not far away, drawn by the sound

of her

troubled breathing, I found the mare. She lay on her side on the

ground,

gasping, her noble coat covered with dirt and grass. Hearing my

footsteps she

lifted her head a little, and followed me with the terrible stare of a

spooked

horse. She was not wounded but worn out. She gave birth eight months

later to a

foal: in every way normal, I was told. Here

Trachi’s direct traces vanish. But, as some may perhaps remember, over

the

following days the newspapers reported a strange series of

horse-rustlings, all

perpetrated with the same technique: a door knocked down, the halter

undone or

ripped off, the animal (always a mare, and always alone) led into a

nearby

wood, to be discovered there exhausted. Only once did the abductor seem

to meet

any resistance: his chance companion of that night was found dying, her

neck

broken. There were

six of these episodes, and they were reported in various places on the

peninsula, occurring one after the other from north to south—in

Voghera, in

Lucca, near Lake Bracciano, in Sulmona, in Cerignola. The last happened

near

Lecce. Then nothing else. But perhaps this story is linked to a strange

report

made to the press by a fishing crew from Puglia: just off Corfu, they

had come

upon “a man riding a dolphin.” This odd apparition swam vigorously

toward the

east; the sailors shouted at it, at which point the man and the gray

rump sank

under the water, disappearing from view. ♦ (Translated,

from the Italian, by Jenny McPhee.) Sign up for the

daily newsletter: the best of The New Yorker every day.

|