|

Berlin có 1 thời là

người yêu của Akhmatova. Trong cuốn "Akhmatova,

thi sĩ, nhà tiên tri", có nhắc tới mối

tình của họ. Vào ngày Jan 5,

1946, trước khi về lại Anh [Berlin khi đó

là Thư ký thứ nhất của Tòa ĐS Anh ở Moscow],

Berlin xin gặp để từ biệt. Sounds die away in the ether, (II, p. 237) Tiếng buồn nhạt nhòa

vào hư vô The last poem of the cycle, written

on January 11, 1946, was more prophetic than Akhmatova realized: We hadn't breathed the poppies'

somnolence, Bài thơ chót

trong chuỗi thơ, hoá ra còn tiên tri hơn nhiều, so với

dự đoán của Anna Akhmatova: Chúng ta

không thở cái mơ mơ màng của 1 tên phi xì ke (II, p. 239) In 1956, something unexpected

happened: the man who was to become "Guest

from the Future" in her great work Poem Without

a Hero-Isaiah suddenly returned to Russia. This was

the famous "meeting that never took place”. In her poem,

"A Dream" (August 14, 1956), Akhmatova writes:

This dream was prophetic or not

prophetic . . . (II, p. 247) Vào năm 1956, một điều

không đợi chờ, xẩy ra. “Người Khách từ Tương Lai” bất thình lình trở lại.

Đây là cuộc “gặp gỡ chẳng hề xẩy ra” nổi tiếng. Giấc mơ này,

tiên tri hay không tiên tri… Nó thì ở trong

mọi thứ, mọi điều… ở Bach Chacome. Another poem, "In a Broken Mirror"

(1956), has the poet compare Petersburg

to Troy at the moment when Berlin came before,

because the gift of companionship that he brought her

turned out to poison her subsequent fate:

The gift you gave me Một bài thơ khác, “Trong cái gương bể” (1956), thi sĩ so sánh St. Petersburg với Troy, vào lúc mà Berlin tới, trước đó, bởi là vì món quà bạn bè mà chàng mang đến cho nàng hóa ra là thuốc độc đối với số phận của nàng sau đó. Món quà anh đem cho tôi Không phải từ bàn thờ. Mà có vẻ như từ cơn đãng trí uể oải của anh Vào cái đêm lửa cháy đó Và nó trở thành thuốc độc chậm Trong cái phần số bí ẩn của tôi Và nó là điềm báo cho tất cả những bất hạnh của tôi- Đừng thèm nhớ nó!... Vẫn xụt xùi ở nơi góc nhà, là, Cuộc gặp gỡ chẳng hề xẩy ra Vargas Llosa, trong "Wellsprings", vinh danh I. Berlin, gọi ông là “vì anh hùng của thời chúng ta, a hero of our time”. Bài viết này, thật quan trọng đối với Mít chúng ta, do cách Berlin diễn giải chủ nghĩa Marx, cách ông ôm lấy, embrace, những tư tưởng thật đối nghịch... TV tính đi bài này, lâu rồi, nhưng quên hoài. Trong "Nửa Thế Kỷ Của Tôi", tuyển tập văn xuôi của Anna Akhmatova, có trích mấy đoạn, trong Nhật Ký, bà viết về thành phố của bà. Post lên đây như “chim mồi”, lấy hứng, viết về Sài Gòn Của Gấu ngày nào. Và Hà Nội ngày nào, vì Saigon không có mùa đông! http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2014/10/23/message-21st-century/?insrc=hpma Isaiah Berlin

Thông điệp gửi thế kỷ 21

NYRB 23 tháng 10, 2014Hai mươi năm trước đây, vào ngày 25 tháng 11, 1994, Isaiah Berlin được trao bằng Tiến sĩ danh dự Luật, tại Đại học Toronto. Sau đây là thông điệp của ông, mà ông gọi là “cương lĩnh ngắn”, gửi 1 người bạn, nhờ đọc giùm, bữa đó. “Đây là thời đẹp nhất của mọi thời, nó cũng là thời mạt hạng” Với những từ này Dickens mở ra cuốn tiểu thuyết nổi tiếng của ông, “Chuyện hai thành phố”. Nhưng áp dụng chúng vào thế kỷ khủng khiếp của riêng chúng ta, thì không thể. Một ngàn năm con người làm thịt lẫn nhau, nhưng những thành quả giết người lớn lao của những bạo chúa như Attila, Thành Cát Tư Hãn, Nã Phá Luân (giới thiệu cái trò giết người tập thể trong chiến tranh), ngay cả những vụ tàn sát người Armenian, thì cũng trở thành nhạt nhòa, trước Cách Mạng Tháng Mười, và sau đó; đàn áp, bách hại, tra tấn, sát nhân ở ngay ngưỡng cửa Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mao, Pol Pot, và cái trò ngụy tạo có hệ thống thông tin, để bưng bít những tội ác ghê rợn này trong bao năm trời - những trò này, trước đó, chưa hề có. Chúng không phải là tai họa thiên nhiên, mà do con người gây ra, và bất cứ ai tin vào định mệnh thuyết, tin rằng đây là tất yếu của lịch sử, thì cũng đếch được: chúng, đúng ra, không thể xẩy ra. Tôi nói, với cảm nghĩ đặc thù, bởi là vì tôi là 1 anh già, quá già, và tôi sống hầu như trọn thế kỷ. Đời tôi thì êm ả, và tôi cảm thấy xấu hổ, khi phải so với cuộc đời của rất nhiều người khác. Tôi không phải là sử gia, và vì thế, tôi không thể nói, bằng quyền uy, về những duyên do của những điều ghê rợn đó. Nhưng có lẽ, tôi có thể cố. Chúng, theo cái nhìn của tôi, không được gây nên bởi những tình cảm tiêu cực bình thường, thông thường, của con người, như Spinoza gọi - sợ hãi, tham lam, thù hận bộ lạc, ghen tuông, yêu quyền lực - tuy rằng, lẽ dĩ nhiên, chúng có phần quỉ ma ở trong đó. Vào thời của chúng ta, chúng được gây nên bởi tư tưởng, hay đúng hơn, một tư tưởng đặc biệt. Quả là nghịch ngạo, Marx, ngồi viết ra những dòng chữ về sự quan trọng của tư tưởng so với những sức mạnh xã hội và kinh tế vô ngã (impersonal), và chính những dòng chữ này đã gây nên sự chuyển đổi (transformation) của thế kỷ 20, cả về hướng, như ông ta muốn, và, bằng phản ứng ngược, ngược lại nó. Nhà thơ Đức Heine, trong 1 trong những bài viết nổi tiếng của ông, đã nói với chúng ta, chớ coi thường nhà triết gia trầm lặng ngồi ở bàn làm việc của mình; nếu Kant không huỷ bỏ, undone, thần học, Robespierre đã không cắt đầu Vua nước Pháp.

Berlin có 1 thời là

người yêu của Akhmatova. Trong cuốn "Akhmatova, thi

sĩ, nhà tiên tri", có nhắc tới mối tình của họ.

Vào ngày Jan 5,

1946, trước khi về lại Anh [Berlin khi đó là Thư

ký thứ nhất của Tòa ĐS Anh ở Moscow], Berlin xin gặp

để từ biệt. Sounds die away in the ether, (II, p. 237) Tiếng buồn nhạt nhòa

vào hư vô The last poem of the cycle,

written on January 11, 1946, was more prophetic than Akhmatova realized: We hadn't breathed the poppies'

somnolence, Bài thơ chót trong

chuỗi thơ, hoá ra còn tiên tri hơn nhiều, so với dự đoán của Anna Akhmatova: Chúng ta

không thở cái mơ mơ màng của 1 tên phi xì ke (II, p. 239) In 1956, something unexpected

happened: the man who was to become "Guest from

the Future" in her great work Poem Without a Hero-Isaiah

suddenly returned to Russia. This was the famous "meeting

that never took place”. In her poem, "A Dream" (August 14,

1956), Akhmatova writes: This dream was prophetic or

not prophetic . . . (II, p. 247) Another poem, "In a Broken Mirror"

(1956), has the poet compare Petersburg to Troy

at the moment when Berlin came before, because the gift

of companionship that he brought her turned out to poison

her subsequent fate: The gift you gave me (II, p. 251)

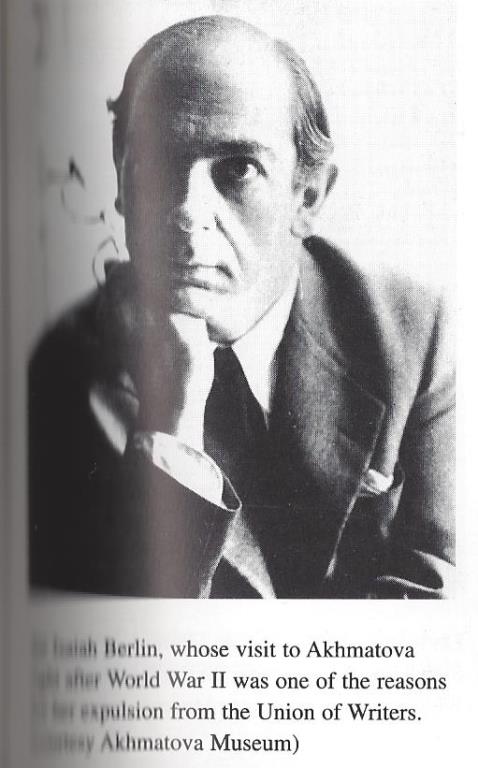

Sir Isaiah Berlin.

Cuộc thăm viếng Anna Akhmatova của ông liền sau Đệ Nhị Thế Chiến,

là một trong những lý do khiến bà bị tống ra khỏi Hội Nhà Văn

.

Thông điệp gửi thế kỷ 21 Isaiah Berlin: A Hero of Our Time

A discreet philosopher

Many years ago, I

read in Spanish translation a book on Marx which was so clear, suggestive

and unprejudiced that I spent a long time looking for other books by its author,

Isaiah Berlin. I later discovered that until recently his work had been difficult

to find since it was scattered, if not buried, in academic publications.

With the exception of his books on Vico and Herder, and the four essays on

freedom, which were available in the English language world, most of his

work led the quiet life of the library and the specialist journal. Now, thanks

to a former student of his, Henry Hardy, who has collected together his essays,

these are now available in four volumes: Russian Thinkers, Against the

Current, Concepts and Categories and Personal Impressions. Một triết gia kín đáo This is an important event since Isaiah Berlin - a Latvian, brought up and educated in England, where he has been Professor of Social and Political Theory in Oxford and President of the British Academy - is one of the most exceptional minds of our time. He is a political thinker and essayist of extraordinary breadth whose work provides a rare pleasure in its skill and brilliance as well as offering an invaluable guide for understanding, in all their complexity, the moral and historical problems faced by contemporary man. Professor Berlin believes passionately in ideas and in the influence that these ideas have on the behavior of individuals and societies, although, at the same time, as a good pragmatist, he is aware of the space that usually opens up between ideas and the words that seek to express them and between the words and the deeds that purport to put them into practice. Despite their intellectual density, his books never seem abstract to us - unlike, for example, the work of Michel Foucault or the latest books of Roland Barthes - or the result of a speculative and rhetorical virtuosity that has, at some moment, cut its moorings with reality. Instead, they are deeply rooted in the common experience of the people. The collection of essays, Russian Thinkers, is an epic fresco of nineteenth-century Russia in intellectual and political terms, but the most outstanding characters are not people but ideas: these shine, move around, challenge each other and change with the vigor of heroes in an adventure novel. In that other beautiful book on a similar theme - To the Finland Station by Edmund Wilson – the thoughts of the protagonists seem to transpire from the persuasive and varied portraits that the author draws of his characters. Here, by contrast, it is the concepts that they formulated, the ideals and arguments with which they confronted each other, and their intuitions and knowledge which define the figures of Tolstoy, Herzen, Belinski, Bakunin and Turgenev, which make them plausible or reprehensible. But even more than Russian Thinkers, it is the collection Against the Current that will doubtless remain as the major contribution of Professor Berlin to the culture of our time. Each essay in this magisterial work reads like a chapter of a novel whose action takes place in the world of thought and in which the heroes and the villains are ideas. Thanks to this scholar who never loses a sense of balance ·and who can clearly see the wood for the trees, Machiavelli, Vico, Montesquieu, Hume, Sorel, Marx, Disraeli and even Verdi arc seen to have a great contemporary significance and the things that they believed, put forward or criticized illuminate in a powerful way the political and social conflicts that we wrongly considered to be specific to our age. The most surprising thing about this thinker is that he appears, at first sight, not to offer ideas of his own. It might seem nonsense to say this, but it is not nonsense because when one reads him, one has the impression that in these essays, Isaiah Berlin achieves what, after Flaubert (and because of him), most modern novelists have tried to achieve in their novels: to erase themselves, to make themselves invisible, to offer the illusion that their stories are self-generated. There are many techniques for 'making the narrator disappear' in a novel. The technique that Professor Berlin uses to make us feel that he is not behind his texts is 'fair play'. This is the scrupulous moral purity with which he analyses, exhibits, summarizes and quotes the thoughts of others, considering all their arguments, weighing up the extenuating circumstances, the constraints of the age, never pushing the words or ideas of others. in one direction or another to make them appear similar to his own. This objectivity in the transmission of the inventions of others gives rise to the fantastic impression that, in these books which say so many things, Isaiah Berlin himself has nothing of his own to say. This is, of course, a rigorously false impression. 'Fair play' is only a technique which, like all narrative techniques, has only one function: to make the content more persuasive. A story that seems not to be told by anyone in particular, which pretends to be making itself, by itself at the moment of reading, can often be more plausible and engrossing for the reader. A thought that seems not to exist by itself, that reaches us indirectly, through what certain eminent men from different epochs and cultures thought at specific moments in their life, or one that professes to be born not out of the creative effort of an individual mind, but rather out of the contrast between the philosophic and political conceptions of others and the gaps and errors in these conceptions, can be more convincing than a thought that is presented, simply and arrogantly, as a single theory. The discretion and modesty of Isaiah Berlin are, in fact, a wily stratagem. He is a 'reformist' philosopher, a defender of individual sovereignty, convinced both of the need for change and social progress and of the inevitable concessions that the latter demands of the former. He is a believer in freedom as an alternative undertaking for individuals and nations, although he is aware of the obligations that economic, cultural and political conditions bring to bear on this option for freedom and is a clear defender of 'pluralism', that is, of tolerance and of the coexistence of different ideas and forms of life, and a resolute opponent of any form of despotism, be it intellectual or social. This all obviously says something about the man, but it is also, to some extent, a way of depriving the reader of the pleasure of discovering these ideas through that lingering, subtle and indirect method - a novelist's method - that Professor Berlin uses to expound his convictions. A few years back, I lost my taste for political utopias, those apocalypses that promise to bring heaven down to earth: I now know that they usually lead to injustices as serious as those they hope to put to right. Since then, I have thought that common sense is the most valuable of political virtues. Reading Isaiah Berlin, I have come to see clearly something that I had intuited in a confused way. That real progress, which has withered or overthrown the barbarous practices and institutions that were the source of infinite suffering for man, and has established more civilized relations and styles of life, has always been achieved through a partial', heterodox and deformed application of social theories. Social theories in the plural, which means that different, sometimes irreconcilable, ideologies have brought about identical or similar forms of progress. The prerequisite was always that these systems should be flexible and could be amended and reformed when they moved from the abstract to the concrete and came up against the daily experience of human beings. The filter at work, which separates what is desirable from what is not desirable in these systems, is the criterion of practical reason. It is a paradox that someone like Isaiah Berlin, who loves' ideas so much and moves among them with such case, is always convinced that it is ideas that must give way if they come into contradiction with human reality, since if the reverse occurs, the streets are filled with guillotines and firing-squad walls and the reign of the censors and the policemen begins. Of the authors that I have read in the past few years, Isaiah Berlin is the one who has impressed me the most. His philosophical, historical and political opinions seem to me illuminating and instructive. However, I feel that although perhaps few people in our time have seen in such a penetrating way what life is - the life of the individual in society, the life of societies in their time, the impact of ideas on daily experience - there is a whole other dimension of man that does not appear in his vision, or does so in a furtive way: the dimension that Georges Bataille has described better than anyone else. This is the world of unreason that underlies and sometimes blinds and kills reason; the world of the unconscious which, in ways that are always unverifiable and very difficult to detect, impregnates, directs and sometimes enslaves consciousness; the world of those obscure instincts that, in unexpected ways, suddenly emerge to compete with ideas and often replace them as a form of action and can even destroy what these ideas have built up. Nothing could be further from the pure, serene, harmonious, lucid and healthy view of man held by Isaiah Berlin than this sombre, confused, sickly and fiery conception of Bataille. And yet I suspect that life is probably something that embraces and mixes these two enemies into a single truth, in all their powerful incongruity. Washington, DC, November 1980 Vargas Llosa: Making Waves Note: Bài viết này, sau được in lại, nhưng mở rộng thêm ra, trong Giếng Khôn, Wellsprings, sau khi Vargas Llosa được Nobel văn chương, như để vinh danh những người ảnh hưởng lên ông.

|