|

ARS EROTICA By Mario

Vargas Llosa, from Notes on the Death of Culture: Essays on Spectacle

and

Society, out next month from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Vargas Llosa,

who is

the author of more than a dozen novels, received the Nobel Prize for

Literature

in 2010. Translated

from the Spanish by John King. A few years

ago, a small media storm erupted in Spain when the Socialist government

in the region of

Extremadura introduced, as part of its sex-education curriculum,

masturbation

workshops for girls and boys over the age of thirteen-a program that it

somewhat

mischievously called Pleasure Is in Your Own Hands. Faced with

protests, the

regional government argued that sex education for children was

necessary to

"prevent undesirable pregnancies" and that masturbation classes would

help young people "avoid greater ills." In the ensuing debate, the

regional

government of Extremadura received support from the regional government

of

Andalucfa, which announced that it would soon roll out a similar

program. An

attempt by an organization close to the Popular Party to close down the

masturbation workshops by way of a legal challenge-called, equally

mischievously, Clean Hands-failed when the public prosecutor's office

refused

to take up the complaint. In the darkness

of earliest times, animals and humans alike engaged in a physical coupling

without mystery, without grace, without subtlety, and without love. The humanization

of the lives of men and women was a long process in which the advance of

scientific knowledge and philosophical and religious ideas all played their

parts, as did the development of arts and letters. But nothing changed as

much as our sex lives did. This change has been a stimulus of artistic and

literary creation; in reciprocal fashion, painting, literature, music, sculpture,

and dance-all the artistic manifestations of human imagination- have contributed

to the enrichment of pleasure in sexual activity. It would not be outrageous

to say that eroticism marks a high point of civilization or that it is one

of civilization's defining characteristics. There is no better way to gauge

how primitive a community is or how far it has advanced in civilization than

to scrutinize the secrets of the bedroom and to find out how its inhabitants

make love. Without attention to the forms and rituals that enrich, prolong, and sublimate pleasure, the sex act would again become a purely physical exercise-a natural drive in the human organism, devoid of sensitivity and emotion. A good illustration of this today can be found in the trashy literature that purports to be erotic but achieves only the vulgar rudiments of the genre-pornography. Erotic literature becomes pornographic for purely literary reasons: a sloppy use of form. When writers are negligent or clumsy in their use of language, their plot construction, their use of dialogue, their description of a scene, they inadvertently reveal everything that is crude and repulsive in a sexual coupling devoid of feeling and elegance-one that lacks a mise-en-scene-which becomes the mere satisfaction of the reproductive instinct. Making love in our time, in the Western world, is much closer to pornography than to eroticism. The masturbation workshops that young people will attend in the future as part of their school curriculum might appear to be a daring step forward in the struggle against prig-gishness and prejudice. In reality it is likely that this and other initiatives designed to demystify sex-revealing it as something as commonplace as eating, sleeping, and going to work-will prematurely disillusion future generations. Without mystery, passion, fantasy, and creativity, sex becomes a banal gymnastic workout. If we want physical love to enrich people's lives, let us free it from prejudice but not from the rites that embellish and civilize it. Instead of exhibiting it in broad daylight, let us preserve the privacy and discretion that allow lovers to play at being gods, to feel that they are gods, in those intense and unique instances of shared passion and desire. Harper’s Magazine July 2015 Về đường học

vấn, ông cậu của Gấu phải nói là dở, mọi đường khác, ông hơn hẳn Gấu.

Nhớ,

những lần may tay đầu tiên trong đời, sau khi tới đỉnh, Gấu vẫn thường

tự hỏi

làm sao mà ông cậu của mình lại khám phá ra nó, hà hà! Bà Trẻ của Gấu,

người nuôi Gấu những ngày đầu tới Sài Gòn, thời kỳ ở hẻm Đội Có Phú

Nhuận, Gấu đã

kể sơ sơ trong Lần Cuối Sài Gòn.

Trong lần tái ngộ Huỳnh Phan Anh ở

Paris, Gấu

có nhờ anh về trao cho gia đình ông cậu Hồng cuốn sách, và sau đó, đến

khi Gấu

về lại Sài Gòn thì ông cậu đã mất. Bà vợ, mợ Hồng, kể cho Gấu nghe, ông

cậu Gấu

có đọc, và rất ư là bực, cái cảnh kể lại, ông cậu đập đầu bưng bưng vào

tuờng,

mỗi khi bị bà chị, - Dì Nhật, với Gấu - chì chiết. Bà Dì này thực

quá khủng khiếp. Để trốn Bà, mỗi lần Bà ca cẩm với Bà Trẻ, tại làm sao

lại phải

nuôi thằng Trụ, sao không để cho mẹ ruột nó lo, là Gấu bèn trốn đến nhà

bạn Cẩn,

Phạm Năng Cẩn, một trong Thất Hiền, ở khu Trương Ming Giảng, gần đó,

hoặc trốn lên nhà bạn Chất, em ông

TTT, để ăn

chực. Trốn tới nhà bạn Chất, là

phải đi bộ suốt con đường từ ngã tư Phú

Nhuận tới

Xóm Gà, phía sau tòa hành chánh Gia Định. Ui chao nhớ

lại sướng làm sao, chẳng thấy 1 tí khổ, mà chỉ bồi hồi cảm động. Bà Trẻ Gấu thương Gấu, có lẽ 1 phần là vì ông con trai học dốt quá, không có lấy 1 tí thông minh của Mẹ. Mà có thể còn là vì ông bố của Gấu nữa. Hai người cùng học sư phạm, Bà Trẻ chắc có cái bằng Tiểu Học, còn bố Gấu, Trung Học, của Tẩy. Đang học thì bị gia đình kêu về lấy chồng, tức ông Nghị, 1 trong những ông Ngoại của Gấu, thế chỗ cho bà chị ruột, chết vì bịnh, chủ yếu là giữ lấy cái gia tài của ông Nghị. Bà mẹ Gấu có lần cũng nói, đúng ra là bà Nghị lấy bố mày, nhưng là do cái gia tài của người chị không thể để lọt vào tay người khác. Bà Trẻ Gấu thương Gấu, có lẽ 1 phần là vì ông con trai học dốt quá, không có lấy 1 tí thông minh của Mẹ. Mà có thể còn là vì ông bố của Gấu nữa. Hai người cùng học sư phạm, Bà Trẻ chắc có cái bằng Tiểu Học, còn bố Gấu, Trung Học, của Tẩy. Đang học thì bị gia đình kêu về lấy chồng, tức ông Nghị, 1 trong những ông Ngoại của Gấu, thế chỗ cho bà chị ruột, chết vì bịnh, chủ yếu là giữ lấy cái gia tài của ông Nghị. Bà mẹ Gấu có lần cũng nói, đúng ra là bà Nghị lấy bố mày, nhưng là do cái gia tài của người chị không thể để lọt vào tay người khác.

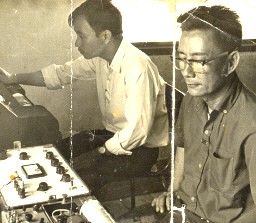

Gấu đang gửi Radiophoto cho UPI. 1958. Học

xong Trung học tôi thi vô Trường Quốc Gia Bưu Điện vừa mới được thành

lập sau một

năm lân la làm quen cái không khí đầy nao nức của tương lai như đang

giục giã ở

ngay đầu ngã tư của cuộc đời, ở đại giảng đường Đại Học Khoa Học. Bạn thử tưởng tượng một học sinh nghèo, sống chui rúc ở cuối con hẻm Đội Có, Phú Nhuận, nơi đám người nghèo khổ bám quanh thành phố, khi chiến tranh chưa dồn dập đem những tiện nghi đến tận giường ngủ, xó bếp, rồi lấy đi một số người thân, quanh năm chỉ biết xài đèn dầu, uống nước giếng. Đám thanh niên, ngoài những lúc tự an ủi lẫn nhau bằng những mối tình tưởng tượng, bằng những tiếng hát nhái theo giọng Út Trà Ôn, Trần Văn Trạch quanh cây đàn ghi ta bên cạnh giếng nước, vào những lúc con xóm sau một ngày mệt lả, mặc tình cho bóng đêm và muỗi đói hành hạ; buổi sáng chỉ còn cách kéo nhau ra mấy dẫy nhà lụp xụp, mặc tình ngắm nghía mấy cô gái họ vẫn thường trầm trồ, mỗi lần thoáng thấy bóng. Các cô lúc này xắn quần cao, thoăn thoắt giữa đám rau muống xanh um phủ kín mấy vũng nước đen ngòm, nguồn lợi thứ nhì sau mấy ao cá, một nơi chốn hẹn hò khác nữa của các cô cậu choai choai, và của đám con nít; bỗng một ngày đẹp trời, thấy như Alice lạc vào xứ thần tiên, lạc vào trường Đại Học Khoa Học. Phở hồi đó ba đồng một tô. Tiền ông Diệm, như sau này người dân Sài-gòn vẫn thường xuýt xoa, tiếc nhớ một hoàng kim thời đại khi chưa nếm mùi Giải Phóng, và tệ hơn, mùi Cộng Sản, thảm hơn nữa, Cộng Sản Bắc Việt. Những buổi sáng hiếm hoi trong túi có mấy đồng bạc cắc bà Trẻ thương tình giấu giếm cho, nhân bữa trước bán hết mấy món đồ xi cho mấy cô gái, mỗi lần đi chợ Phú Nhuận, sau khi mua mớ rau, con cá, vẫn thường xúm quanh cái mẹt của bà già Bắc Kỳ, mân mê chiếc vòng mã não, chiếc cà rá hình trái tim, cây lược lưỡi liềm, tấm gương bầu dục phía sau có hình mấy nghệ sĩ cải lương... tôi có cảm tưởng cả con hẻm, khu phố cũng xôn xao cùng tôi qua những hương vị buổi sáng của nó: Tô phở nơi đình làng Phú Nhuận, trong hơi phở có chút hiền từ của khói nhang, của những lời cầu khấn, mấy bà mấy cô đi chợ tiện thể ghé đình lạy Phật và dùng điểm tâm. Dĩa bánh ướt của cô gái trong xóm với đôi quang gánh lúc nào cũng lao về phía trước, chỉ chậm lại nơi đầu con hẻm mươi, lăm phút rồi lại tất tả chạy quanh xóm. Có bữa dù đã chạy vội từ nhà, khi ra tới nơi chỉ còn kịp nhìn thấy một nửa bóng dáng cùng cử chỉ quen thuộc của cô còn nán lại phía sau lưng đòn gánh. Khi đã đi làm, có lương tháng, có nhà ở, do cơ quan cấp, bị dòng đời xô đẩy không cho ngoái cổ nhìn lại con hẻm xưa, có những buổi sáng chạy xe vòng vòng đuổi theo dư âm ngày tháng cũ, biết đâu còn sót lại qua dĩa bánh cuốn Thanh Trì, nơi con hẻm đường Trần Khắc Chân, khu Tân Định. Thứ bánh cuốn mỏng tanh, không nhân, chấm nước mắm nhĩ màu mật, cay xè vị ớt bột, kèm miếng đậu phụ nóng hổi, dòn tan, miếng chả quế, giò lụa. Chủ nhật đổi món bún thang dậy mùi mắm tôm, khi đã no nê vẫn còn thèm thuồng chút thơm tho của đôi ba giọt cà cuống đầu tăm. Nhìn bước đi của thời gian, của thành phố trong cơn tuyệt vọng chạy đua với chiến tranh, trong nỗi hối hả đi tìm ông chủ đích thực, sau những ông chủ thuộc địa, thực dân cũ, thực dân mới... cuối cùng khám phá ra đó chính là kẻ thù... Nhìn bước đi thời gian trên khuôn mặt xinh tươi của mấy cô con gái bà chủ tiệm, mới ngày nào còn tranh giành đồ chơi, còn tị nạnh đùn đẩy nhau trong việc phục vụ khách, bây giờ đã biết đỏ mặt trước mấy cậu thanh niên. Tự nhủ thầm hay là tới 79 đợi một tô phở đặc biệt sau khi len lỏi qua các dẫy bàn chật cứng thực khách, cố tìm một cái ghế trống. Hay tới quán bà Ba Bủng để rồi lưỡng lự, giữa một tô bún ốc; cố tìm lại hình bóng con ốc nhồi ngày xưa, tại một vùng quê của xứ Bắc Kỳ xa lơ xa lắc, chỉ muốn quên đi, chỉ muốn chối từ nhưng cuối cùng khám phá ra, trong đáy sâu âm u của tâm hồn, của tiềm thức, của quá khứ, hiện tại, tương lai, của hy vọng, thất vọng, của hạnh phúc, khổ đau... vẫn có một con ốc nhồi ẩn náu dưới mớ bèo trên mặt ao đầy váng; giữa một tô bún riêu, hay một tô bún chả thơm phức vẫn còn chút dư vị chợ Đồng Xuân, mới ngày nào được về Hà-nội ăn học. Ôi tất cả, chỉ vì thèm nghe cho được cái âm thanh ấm áp của mấy đồng bạc cắc reo vui suốt con hẻm Đội Có, Bà Trẻ cho, ngày nào, ngày nào... Bà Trẻ, vợ một

người em ông Ngoại, khi còn con gái nổi tiếng đẹp, thông minh, học

giỏi, được

ra tỉnh học, đột nhiên bị gia đình gọi về quê gấp. Bà đã đành vùi dập

giấc mơ

trở thành cô giáo, để đi lấy chồng, đúng ra là để làm vợ thế cho bà chị

ruột, vợ

ông Nghị, lúc đó bệnh nặng nằm chờ chết. Để nuôi nấng, dạy bảo đứa con

gái còn

đang ẵm ngửa của bà chị, đúng ra, để giữ mớ của cải bên chồng không cho

lọt ra

ngoài, đúng hơn, không rớt tới đám con của mấy bà vợ trước. Ông Nghị, tướng

người cao lớn, mấy đời vợ, mấy dòng con, không kể con rơi con rớt, con

làm phước.

Bà Trẻ kể cho tôi nghe về một cặp vợ chồng hiếm hoi, đã nhờ vả ông. Và

đứa con

gái, kết quả của mối tình "thả cỏ", của một bữa rượu say sưa bên mâm

thịt cầy trong lúc người chồng giả đò mắc bận đi ra bên ngoài, đã bị

câm ngay từ

lúc lọt lòng. Nghe bà kể, tôi mơ hồ nhận ra nỗi thất vọng của một người

đàn bà

đã hy sinh một cách vô ích tuổi trẻ, nhan sắc, sự thông minh và luôn cả

lòng tốt,

tính vị tha của nình. Cậu H. vì không thể là đứa con của hạnh phúc, cho

nên

không được thừa hưởng tính thông minh của người mẹ, vóc dáng cao lớn

của người

cha, nhưng vẫn giữ nguyên được truyền thống của những người đàn ông

trong họ,

luôn coi người đàn bà là chủ trong gia đình. Cậu luôn tỏ ra bất lực

trước người

chị cùng bố khác mẹ, một cô gái tuy chưa đến tuổi lấy chồng mà đã là

gái già.

Những lần bị đay nghiến hành hạ quá mức, cậu chỉ phản ứng bằng cách đập

đầu vào

tường. Âm thanh của sự nhẫn nhục

không chịu dừng lại ở ngưỡng cửa chiến tranh:

Trong những năm miền Nam ngày đêm bị Thần Chết réo đòi mạng, cậu H. đã

áp dụng

khí giới hữu hiệu nhất mà cậu có, là tự hành xác để được hoãn dịch. Cậu

nhịn

ăn, nhịn ngủ, uống cà phê đen đậm đặc, cố làm cho xuống cân, phổi có

vết nám... Không chịu ngừng lại mà

còn vượt xa hơn nữa, tới miền đất của phúc phận, nghiệp

duyên: Cuộc sống gia đình hạnh phúc những năm sau 1975, theo Bà Trẻ, là

do Đức

Phật đã hiểu thấu nỗi khổ đau, lòng ăn chay, niệm Phật của bà, nhưng

tôi cho rằng

Ngài đã bị những tiếng đập đầu binh binh của cậu H. làm giật mình, nhìn

xuống

cõi đời ô trọc này.

|