|

Human life is short. For many people, delving into history's depths is boring, frightening, and they have no time for it. Furthermore, in the West the sense of history has weakened or completely vanished: the West does not live in history; it lives in civilization (by which I mean the self-awareness of transnational technological culture as opposed to the subconscious, unquestioned stream of history). But in Russia there is practically no civilization, and history lies in deep, untouched layers over the villages, over the small towns that have reverted to near wilderness, over the large, uncivilized cities, in those places where they try not to let foreigners in, or where foreigners themselves don't go. Even in the middle of Moscow, within a ten-minute walk from the Kremlin, live people with the consciousness of the fifteenth or eleventh century (the eleventh century was better, more comprehensible to us, because at that time culture and civilization were more developed in Russia than in the fifteenth century). When you have any dealings with these people, when you start a conversation, you feel that you've landed in an episode of The Twilight Zone. The constraints of a short article don't allow me to adequately describe this terrifying feeling, well known to Europeanized Russians, of coming into contact with what we call the absurd, a concept in which we invest far greater meaning than Western people do. Here one needs literature- Kafka, Ionesco; one needs academic scholars like Levy-Bruhl with his study of pre-logical thought. Đời người thì ngắn ngủi. Với nhiều người, cái việc đào bới quá khứ thì chán ngấy, chưa kể đáng sợ, và họ chẳng có thì giờ. Vả chăng, ở 1 xã hội Tây Phương, ý niệm lịch sử yếu dần nếu không muốn nói, biến mất theo với năm tháng: Tây phương không sống với lịch sử, nó sống với văn minh (qua cái từ này, tôi muốn nói 1 thứ tự quan hoài, của 1 nền văn hóa liên quốc gia, mang tính kỹ thuật, đối nghịch với dòng tiềm thức, không tra hỏi của lịch sử). Nhưng ở Nga, gần như không có cái gọi là văn minh, và lịch sử thì nằm trong những tầng sâu, chưa ai mó tới, trên những làng xóm, thành phố nhỏ mấp mé bờ tiền sử, thời hoang sơ, trên những thành phố lớn ở những khu vực rộng, không biết đến cái gọi là có văn hóa, nơi ngăn cấm những người nước ngoài, và chính họ cũng chẳng dám mò tới. Ngay cả ở trung tâm thành phố Moscow, vẫn có những khu vực mà đời sống ở đó, thì “huy hoàng thế kỷ” 15, hay 11; thế kỷ 11 thì dễ hiểu, dễ thông cảm hơn, vì vào thời kỳ này, nước Nga phát triển nhiều về mặt văn hóa, văn minh, so với thế kỷ 15) Tây Phương sống bằng văn minh, Mít sống bằng lịch sử. GCC thuổng ý này, khi viết về Bác Hồ, giống như cái xác ướp của Đức Thánh Trần, thí dụ, từ quá khứ bốn ngàn năm bèn sống lại, hoặc, buồn quá, bèn vỗ vai Hùng Vương, “toa” có công dựng nước, còn “moa”, giữ nước! Trong bài viết "Những Thời Ăn Thịt Người" (Thế Kỷ 21, bản dịch), bà cho rằng, Á Châu sống bằng lịch sử, trong khi Âu Châu, bằng văn minh. Có thể vì sống bằng lịch sử, cho nên, những nhân vật từ đời thuở nào vẫn "bị", hoặc "được" đội mồ sống dậy, nhập thân vào những anh hùng, cha già dân tộc. Có thể cũng vì vậy, câu nói "sĩ phu Bắc Hà chỉ còn có tôi", của Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh, và hình ảnh một Nguyễn Huệ tới Thăng Long, làm tan hoang phủ Chúa, cung Vua, rồi bỏ đi, vẫn "nhức nhối" cho tới bây giờ. Tôi cũng cố tưởng tượng ra một Nguyễn Huệ "của tôi", và tôi nghe Người vừa lắc đầu, vừa lẩm bẩm, khi đứng trước những miếu đền, những ngàn chương sử nay chỉ là một đống tro tàn: "Ta tìm gì ở đây?" "Nơi này, ta không sinh ra, và cũng chẳng hề muốn sống ở đó". During Stalin's time, as I see it, Russian society, brutalized by centuries

of violence, intoxicated by the feeling that everything was allowed, destroyed

everything "alien": "the enemy," "minorities"-any and everything the least

bit different from the "average." At first this was simple and exhilarating:

the aristocracy, foreigners, ladies in hats, gentlemen in ties, everyone

who wore eyeglasses, everyone who read books, everyone who spoke a literary

language and showed some signs of education; then it became more and more

difficult, the material for destruction began to run out, and society turned

inward and began to destroy itself. Without popular support Stalin and his

cannibals wouldn't have lasted for long. The executioner's genius expressed

itself in his ability to feel and direct the evil forces slumbering in the

people; he deftly manipulated the choice of courses, knew who should be the

hors d' oeuvres, who the main course, and who should be left for dessert;

he knew what honorific toasts to pronounce and what inebriating ideological

cocktails to offer (now's the time to serve subtle wines to this group; later

that one will get strong liquor).

It is this hellish cuisine that Robert Conquest examines. And the leading character of this fundamental work, whether the author intends it or not, is not just the butcher, but all the sheep that collaborated with him, slicing and seasoning their own meat for a monstrous shish kebab. Tatyana Tolstaya Lần trở lại xứ Bắc, về lại làng cũ, hỏi bà chị ruột về Cô Hồng Con, bà cho biết, con địa chỉ, bố mẹ bị bắt, nhà phong tỏa, cấm không được quan hệ, và cũng chẳng ai dám quan hệ. Bị thương hàn, đói, và khát, và do nóng sốt quá, khát nước quá, cô gái bò ra cái ao ở truớc nhà, tới bờ ao thì gục xuống chết. Có thể cảm thấy đứa em quá đau khổ, bà an ủi, hồi đó “phong trào”. Tolstaya viết: Trong thời Stalin, như tôi biết, xã hội Nga, qua bao thế kỷ sống dưới cái tàn bạo, bèn trở thành tàn bạo, bị cái độc, cái ác ăn tới xương tới tuỷ, và bèn sướng điên lên, bởi tình cảm, ý nghĩ, rằng, mọi chuyện đều được phép, và bèn hủy diệt mọi thứ mà nó coi là “ngoại nhập”: kẻ thù, nhóm, dân tộc thiểu số, mọi thứ có tí ti khác biệt với nhân dân chúng ta, cái thường ngày ở xứ Bắc Kít. Lúc đầu thì thấy đơn giản, và có tí tếu, hài: lũ trưởng giả, người ngoại quốc, những kẻ đeo cà vạt, đeo kiếng, đọc sách, có vẻ có tí học vấn…. nhưng dần dần của khôn người khó, kẻ thù cạn dần, thế là xã hội quay cái ác vào chính nó, tự huỷ diệt chính nó. Nếu không có sự trợ giúp phổ thông, đại trà của nhân dân, Stalin và những tên ăn thịt người đệ tử lâu la không thể sống dai đến như thế. Thiên tài của tên đao phủ, vỗ ngực xưng tên, phô trương chính nó, bằng khả năng cảm nhận, dẫn dắt những sức mạnh ma quỉ ru ngủ đám đông, khôn khéo thao túng đường đi nước bước, biết, ai sẽ là món hors d’oeuvre, ai là món chính, ai sẽ để lại làm món tráng miệng… Đó là nhà bếp địa ngục mà Conquest săm soi. Và nhân vật dẫn đầu thì không phải chỉ là tên đao phủ, nhưng mà là tất cả bầy cừu cùng cộng tác với hắn, đứa thêm mắm, đứa thêm muối, thêm tí bột ngọt, cho món thịt của cả lũ. Cuốn "Đại Khủng Bố", của Conquest, bản nhìn lại, a reassessment, do Oxford University Press xb, 1990. Bài điểm sách, của Tolstaya, 1991. GCC qua được trại tị nạn Thái Lan, cc 1990. Như thế, đúng là 1 cơ may cực hãn hữu, được đọc nó, khi vừa mới Trại, qua tờ Thế Kỷ 21, với cái tên “Những Thời Ăn Thịt Người”. Không có nó, là không có Gấu Cà Chớn. Không có trang Tin Văn. Có thể nói, cả cuộc đời Gấu, như 1 tên Bắc Kít, nhà quê, may mắn được ra Hà Nội học, nhờ 1 bà cô là Me Tây, rồi được di cư vào Nam, rồi được đi tù VC, rồi được qua Thái Lan... là để được đọc bài viết! Bây giờ, được đọc nguyên văn bài điểm sách, đọc những đoạn mặc khải, mới cảm khái chi đâu. Có thể nói, cả cái quá khứ của Gấu ở Miền Bắc, và Miền Bắc - không phải Liên Xô - xuất hiện, qua bài viết. Khủng khiếp thật! Tatyana Tolstaya, trong một bài người viết tình cờ đọc đã lâu, khi còn ở Trại Cấm, và chỉ được đọc qua bản dịch, Những Thời Ăn Thịt Người (đăng trên tờ Thế Kỷ 21), cho rằng, chủ nghĩa Cộng-sản không phải từ trên trời rớt xuống, cái tư duy chuyên chế không phải do Xô-viết bịa đặt ra, mà đã nhô lên từ những tầng sâu hoang vắng của lịch sử Nga. Người dân Nga, dưới thời Ivan Bạo Chúa, đã từng bảo nhau, người Nga không ăn, mà ăn thịt lẫn nhau. ["We Russians don't need to eat; we eat one another and this satisfies us."]. Chính cái phần Á-châu man rợ đó đã được đưa lên làm giai cấp nồng cốt xây dựng xã hội chủ nghĩa. Bà khẳng định, nếu không có sự yểm trợ của nhân dân Nga, chế độ Stalin không thể sống dai như thế. Puskhin đã từng van vái: Lạy Trời đừng bao giờ phải chứng kiến một cuộc cách mạng Nga! "God forbid we should ever witness a Russian revolt, senseless and merciless," our brilliant poet Pushkin remarked as early as the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Trong bài viết, Tolstaya kể, khi cuốn của Conquest, được tái bản ở Liên Xô, lần thứ nhất, trên tờ Neva, “last year” [1990, chắc hẳn], bằng tiếng Nga, tất nhiên, độc giả Nga, đọc, sửng sốt la lên, cái gì, những chuyện này, chúng tớ biết hết rồi! Bà giải thích, họ biết rồi, là do đọc Conquest, đọc lén, qua những ấn bản chui, từ hải ngoại tuồn về! Bản đầu tiên của nó, xb truớc đó 20 năm, bằng tiếng Anh, đã được tuồn vô Liên Xô, như 1 thứ sách “dưới hầm”, underground, best seller. Cuốn sách đạt thế giá folklore, độc giả Nga đo lường lịch sử Nga, qua Conquest,"according to Conquest," Review of “The Great Terror: A Reassessment, by Robert Conquest” (Oxford University Press, 1990)

LAST YEAR Robert Conquest's The Great Terror was translated into Russian and published in the USSR in the journal Neva. (Unfortunately, only the first edition was published. I hope that the second, revised and enlarged edition will be published as well, if it is not suppressed by the censorship so recently revived in the Soviet Union.) The fate of this book in the USSR is truly remarkable. Many of those who opened Neva in 1989-90 exclaimed: "But I know all this stuff already!" How did they know it? From Conquest himself. The first edition appeared twenty years ago in English, was translated into Russian, and infiltrated what was then a closed country. It quickly became an underground best seller, and there's not a thinking person who isn't acquainted with the book in one form or another: those who knew English read it in the original, while others got hold of the Russian text, made photocopies at night, and passed them on. The book gave birth to much historical (underground and emigre) research, the facts were assimilated, reanalyzed, argued, confirmed, elaborated. In short, the book almost achieved the status of folklore, and many Soviet people measure their own history "according to Conquest," sometimes without realizing that he actually exists. This is why many readers, especially the younger ones, thought of Conquest's book as a compilation of "commonly known facts" when they read it for the first time. The author should be both offended and flattered. He [Conquest] later called Marxism a “misleading mental addiction”. Ông sau đó gọi chủ nghĩa Mác là thứ “say mê, nghiện ngập về mặt tâm thần lầm lạc”. Ngày “Một ngày trong đời Ivan Denisovich” của Solzhenitsyn chính thức ra lò, Thứ Bẩy, 17 Tháng 11, 1962. Cứ như ở trong nhà thờ, ông chủ báo Novy Mir kể lại cho tác giả, tình hình tòa soạn, độc giả lặng lẽ vô, lặng lẽ đưa ra 70 kopeck, lặng lẽ lấy một số báo, và lặng lẽ ra ngoài, nhường chỗ cho độc giả khác! Nhưng, nếu như thế, liệu “Một ngày trong đời Ivan” có thể dài quá một số báo Novy Mir? Không thể, theo Gấu. Đúng như Lukacs, khi nhận định, vào thời điểm Cái Ác lên ngôi, cả văn chương và đời sống bỏ chạy có cờ, thì truyện ngắn đúng là cái anh chàng cảm tử đóng vai hậu vệ, cản đường tiến của nó. (1) “Bếp Lửa, Kẻ Xa Lạ, Một ngày, Tướng về hưu”… bắt buộc phải là truyện ngắn, không thể khác. Hơn thế nữa, chưa cần đọc, chỉ đọc mỗi cái tên truyện không thôi, là đã đủ ngộ ra chân lý. Nhân đang ồn ào về Dương Nghiễm Mậu, lịch sử không thể lập lờ, thế thì, tại nàm sao, trong danh sách trên, lại thiếu, những Rượu Chưa Đủ, Cũng Đành, Ngoại Ô Dĩ An và Linh Hồn Tôi, Con Thú Tật Nguyền, Trăng Huyết, Trái Khổ Qua, Dọc Đường, Tư, và, lẽ dĩ nhiên: “Tứ tấu khúc” viết về Lan Hương và Sài Gòn! Ôi chao, hoá ra Lukacs mới kỳ tài làm sao: ông biết trước, Cái Ác sẽ lên ngôi, và thiên tài của nơi chốn [ông thần đất, ông thành hoàng, ông địa...] sẽ ban cho miền đất bị trù ẻo này hơn một truyện ngắn, trong khi chờ, được chúc phúc trở lại. * (1) G. Lukacs, phê bình gia Mác xít, đọc Một ngày, và đưa ra nhận định như trên, về thể loại truyện ngắn. Trớ trêu là, Robert Conquest, và tiếp theo, Martin Amis, cũng dựa trên kinh nghiệm của Solz, của trại tù Stalin, để giải thích sự dài ngắn của một cuốn sách. Amis mở ra cuốn “Koba The Dread” của ông, bằng câu văn thứ nhì của Robert Conquest, trong cuốn “Mùa Gặt Buồn: Tập thể hóa Xô viết và Trận Đói-Kinh Hoàng: The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine”: Nếu lấy chữ mà so với mạng người, thì những chuyện gì xẩy ra ở trong cuốn sách của tôi, cứ hai mươi mạng người thì tương đương với, không phải một từ, mà một con chữ. Câu tiếng Anh của Conquest, “We may perhaps put this in perspective in the present case by saying that in the actions here recorded about twenty human lives were lost for, not every word, but every letter, in this book”, tương đương với 3,040 mạng người. Cuốn sách của ông dài 411 trang. Conquest trích một câu của Grossman, câu này tương đương với 3.880 mạng trẻ em: "And the children's faces were aged, tormented, just as if they were seventy years old. And by spring they no longer had faces. Instead, they had birdlike heads with beaks, or frog heads-thin, wide lips-and some of them resembled fish, mouths open" [Mặt trẻ em thì già cằn, tả tơi, cứ như thể chúng 70 tuổi đầu. Tới mùa xuân chẳng em nào còn có mặt, thay vì mặt thì là những cái đầu giống như đầu chim...]

Ai Điếu Robert Conquest

Thay vì đi 1 đường tưởng niệm, Tin Văn sẽ dịch bài viết của Tolstaya, khi

điểm cuốn của Conquest. Nhờ bài viết này, đọc bản dịch, hay tóm tắt chẳng

biết nữa, “Những Thời Ăn Thịt Người”, trên tờ Thế Kỷ 21, tại Trại tạm cư

Panat Nikhom, cc 1989, Gấu mới ngộ ra Cái Ác Bắc KítTay này, khui ra sự thực về Stalin: Một Con Quỉ Robert Conquest obituary Historian and poet who exposed the full extent of Stalin’s terror during the Soviet era http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/aug/05/robert-conquest Trong những sử gia Tây Phương về Liên Xô, Robert

Conquest, mất 3/8/2015, 98 tuổi có 1 vị trí độc nhất. Ông không chỉ là người

thứ nhất viết về khủng bố Stalin, mà còn là người chi tiết nhất, chính xác

nhất về nó: Người nói sự thực về khủng bố Xì, và về tên bạo chúa sát nhân,

the man who told the truth about the terror, and Stalin’s murderous tyranny.

The Great Terror and the Little Terror

LAST YEAR Robert Conquest's "The Great Terror" was translated into Russian

and published in the USSR in the journal Neva. (Unfortunately, only the first

edition was published. I hope that the second, revised and enlarged edition

will be published as well, if it is not suppressed by the censorship so recently

revived in the Soviet Union.) The fate of this book in the USSR is truly

remarkable. Many of those who opened Neva in 1989-90 exclaimed: "But I know

all this stuff already!" How did they know it? From Conquest himself. The

first edition appeared twenty years ago in English, was translated into Russian,

and infiltrated what was then a closed country. It quickly became an underground

best seller, and there's not a thinking person who isn't acquainted with

the book in one form or another: those who knew English read it in the original,

while others got hold of the Russian text, made photocopies at night, and

passed them on. The book gave birth to much historical (underground and emigre)

research, the facts were assimilated, reanalyzed, argued, confirmed, elaborated.

In short, the book almost achieved the status of folklore, and manyReview of “The Great Terror”: A Reassessment, by Robert Conquest (Oxford University Press, 1990) ..... Conquest does ask this question in regard to Stalin and his regime: he meticulously and wittily examines the possible motives of Stalin's behavior, both rational and irrational; he shows the deleterious effect of Bolshevik ideology on the mass consciousness, how it prepared the way for the Terror. A particularly wonderful quality of this book is also that when questions, ideas, or suppositions arise in you, the reader, the author invariably answers these mental queries a few pages later, develops the thought you've had, and figures things out along with you, bringing in more arguments on both sides than you ever thought possible. I was especially struck by this in the third chapter, "Architect of Terror," which sketches a psychological portrait of Stalin, and in the fifth chapter, "The Problem of Confession," where Conquest explores the motivations and behavior of Stalin's victims. This book is not a storeroom of facts but a profoundly analytical investigation. Instead of getting tangled up in the abundance of information, you untangle the knots of the Soviet nightmare under the author's patient direction. Having finished this book, no one can ever again say: "I didn't know." Now we all know. Và có lẽ phải dùng tới thuật ngữ của Conquest, khi ông nhìn lại thế kỷ tan hoang vừa qua, trong cuốn sách của ông [Reflections on a Ravaged Century, by Robert Conquest, New York W.W. Norton & Company, 317 pages, $26.95] : Mindslaughter. Làm thịt cái đầu. Đây chính là chấn thương nặng nề mà Miền Bắc đã 'cưu mang' khi đánh chiếm Miền Nam. Con bọ VC là gì nếu không phải là một thứ sinh vật bị làm thịt mất cái đầu, của con người, và thay vào đó, của con bọ? Bởi thế, một nhà phê bình, Michael Young, khi đọc cuốn của Conquest, đã ban cho ông cái tên, Đại Phán Quan, Grand Inquisitor. ***** Review of “The Great Terror: A Reassessment, by Robert Conquest” (Oxford

University Press, 1990)

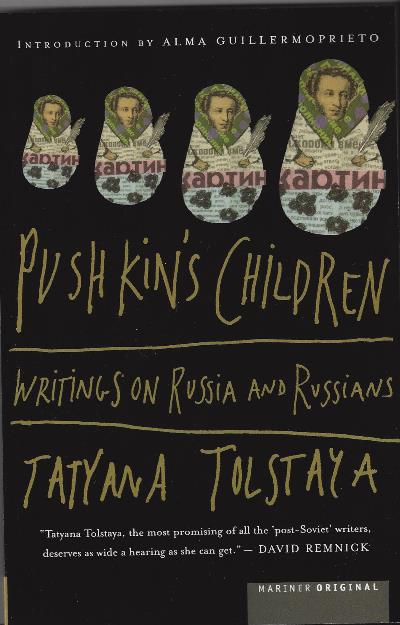

LAST YEAR Robert Conquest's The Great Terror was translated into Russian and published in the USSR in the journal Neva. (Unfortunately, only the first edition was published. I hope that the second, revised and enlarged edition will be published as well, if it is not suppressed by the censorship so recently revived in the Soviet Union.) The fate of this book in the USSR is truly remarkable. Many of those who opened Neva in 1989-90 exclaimed: "But I know all this stuff already!" How did they know it? From Conquest himself. The first edition appeared twenty years ago in English, was translated into Russian, and infiltrated what was then a closed country. It quickly became an underground best seller, and there's not a thinking person who isn't acquainted with the book in one form or another: those who knew English read it in the original, while others got hold of the Russian text, made photocopies at night, and passed them on. The book gave birth to much historical (underground and emigre) research, the facts were assimilated, reanalyzed, argued, confirmed, elaborated. In short, the book almost achieved the status of folklore, and many Soviet people measure their own history "according to Conquest," sometimes without realizing that he actually exists. This is why many readers, especially the younger ones, thought of Conquest's book as a compilation of "commonly known facts" when they read it for the first time. The author should be both offended and flattered. This is a book about the Stalinist terror, about the Great Terror, which began in the thirties and continued-growing and fading-until the death of the Great Tyrant in 1953. The very expression "Great Terror" leads to the idea of the "Little Terror," which remains necessarily outside the confines of this book. Of course, no one can write a book about Russia that includes everything, explains everything, weaves together the facts and motifs of history, revealing the root system that every so often puts out shoots and suddenly blossoms into the frightful flower of a Great Terror. I'm reminded of the protagonist of Borges's story "Aleph," who tried to create a poem that described the entire universe-but failed, of course. No one can possibly accomplish such a task. The Little Terror in Russia has been around from time immemorial. It has lasted for centuries and continues to this very day. So many books have been written about the Little Terror! Virtually all the literature of the nineteenth century, which is so valued in the West, tells the story of the Little Terror, sometimes with indignation, sometimes as something taken for granted, and tries to understand its causes, explain its mechanisms, give detailed portraits of its victims: individual personalities, entire classes, and the country as a whole. What is Russian society and why is it the way it is? What can and must be done in order to free ourselves of this all-permeating terror, of total slavery, of fear of any and every one? How do we ensure that an individual's fate does not depend on others' whims? Why is it that any revolution, any attempt to rid Russia of terror, leads to an even greater terror? Russia didn't begin yesterday and won't end tomorrow. The attempts of many writers and researchers to explain Russian horrors by the Bolshevik rise to power are naive. The sigh of relief that in recent years has been heard more and more often in the West is naive as well: the cold war is over, Gorbachev has come, and everything will soon be just fine. (The events of the last few months have shown the West what has been clear to Soviet people for almost two years: nothing good can be expected from Gorbachev.) Human life is short. For many people, delving into history's depths is boring, frightening, and they have no time for it. Furthermore, in the West the sense of history has weakened or completely vanished: the West does not live in history; it lives in civilization (by which I mean the self-awareness of transnational technological culture as opposed to the subconscious, unquestioned stream of history). But in Russia there is practically no civilization, and history lies in deep, untouched layers over the villages, over the small towns that have reverted to near wilderness, over the large, uncivilized cities, in those places where they try not to let foreigners in, or where foreigners themselves don't go. Even in the middle of Moscow, within a ten-minute walk from the Kremlin, live people with the consciousness of the fifteenth or eleventh century (the eleventh century was better, more comprehensible to us, because at that time culture and civilization were more developed in Russia than in the fifteenth century). When you have any dealings with these people, when you start a conversation, you feel that you've landed in an episode of The Twilight Zone. The constraints of a short article don't allow me to adequately describe this terrifying feeling, well known to Europeanized Russians, of coming into contact with what we call the absurd, a concept in which we invest far greater meaning than Western people do. Here one needs literature- Kafka, Ionesco; one needs academic scholars like Levy-Bruhl with his study of pre-logical thought. ******* Archaeological digs have been carried out in the ancient Russian city of Novgorod, once an independent republic that carried on independent trade with the West. The earth reveals deep layers of the city's history. In the early ones, from the eleventh or twelfth century, there are many birch-bark documents and letters written by simple people that testify to the literacy of the population. And there are also remains of good leather footwear. In the fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries, when Novgorod had been conquered by Moscow, letters disappear, and instead of leather boots,tapti appear, a kind of slipper-like shoe made from bast. The sixteenth century, when Ivan the Terrible ruled, was also a time of Great Terror, perhaps even the first government-wide terror in Russia, a terror that is horribly reminiscent of Stalinist times. It is particularly appalling in what would seem to be its inexplicableness, its lack of precedent: after all, there wasn't any Lenin, there were no Bolsheviks or revolutions preceding Ivan the Terrible. It was during his reign that someone said: "We Russians don't need to eat; we eat one another and this satisfies us." The backward motion of history, the submersion of culture under a thick layer of gilded, decorative "Asiatic savagery," government piracy, guile elevated to principle, unbridled caprice, extraordinary passivity and lack of will all combined with an impulsive cruelty; incompletely suppressed paganism, undeveloped Christianity; a blind, superstitious belief in the spoken, and especially in the written, word; the sense of sin as a secret and repulsive pleasure (what Russians call Dostoyevskyism). How can all this be described, how can one give a sense of the ocean from which the huge wave of a Great Terror periodically rises? Robert Conquest investigates only the Great Terror, not touching on the Little one. He sees its roots in the Soviet regime that formed before Stalin, in the very principles and organization of the Soviet state. In his own way he is absolutely right; this is true, and every investigation must begin somewhere. I merely wish to remind the reader once again (and Robert Conquest knows this very well) that the Soviet state was not created out of thin air, that its inhabitants were the inhabitants of yesterday's Russian state who awoke one fine morning to find themselves under the so-called Soviet regime. The October revolution and the civil war that soon followed led to the exile and destruction, or de-civilizing, of the Europeanized Russian population (by Europeanized I mean people who were literate, educated; who possessed a work ethic, a developed religious consciousness, respect for law and reason; and who were also familiar with Europe and the achievements of world culture). Those who survived and remained in Russia lost the right to speak their mind and were too frightened or weak to influence anything. Russian society, though it wandered in the dark for centuries, had nonetheless by 19I7 given birth not only to an educated class but to a large number of people with high moral standards and a conscience, to honest people who were not indifferent to issues of social good. This is the intelligentsia - not really a class but a fellowship of people "with moral law in their breast," as Kant put it. Lenin hated them more than anyone else, and they were the first to be slaughtered. When Maxim Gorky wrote to Lenin in their defense, saying that "the intelligentsia is the brain of the nation," Lenin answered with the famous phrase: "It's not the brain, it's the shit." The savage, barbaric, "Asiatic" part of the Russian empire was invited to participate in the "construction of a new world" and its members received certain privileges, some people in word alone, others in fact. What this section of the population really represented, what it was capable of and what it aspired to, no one actually knew, particularly the Soviet leaders, whose notions about the "people" derived exclusively from their own theories; the model for the "worker" was taken from the German or English working class, and the peasant was entirely dreamed up. Arrogant, impatient, cruel, barely literate people took advantage of the historical moment (the war dragging on, the military leadership's lack of talent, thievery in the army and the rear guard; a weak tsar; and after the February Revolution, a weak transitional government, widespread disorder and chaos, a dissatisfied people, etc.) to carry out what they called a revolution but what was actually a counterrevolutionary coup. As is well known, Lenin's initial idea was to hold onto power for no less a period than the French Commune once did. This desire to become a chapter heading in a history text is quite characteristic of bookish, theoretical thinking. Then he intended to suffer a defeat, go underground, and work for a real coup. However, no one ended up taking power away from the Bolsheviks: they were better organized and much more cynical and unscrupulous than any of their opponents. Seizing power turned out not to be too difficult. But governing the Russian empire was almost impossible. (Even today no one knows how.) Terror became useful. In one of his telegrams, Lenin exclaims indignantly: "We're not shooting enough professors." Isn't this a portent of typical Stalinist methods: destruction by category? Under Stalin, arrest by category became a regular thing: today they're killing miners, tomorrow they're destroying railway engineers, then they'll get around to peasants, then historians of local customs (students of local lore, history, and economy were almost completely destroyed for being "spies"). One of my grandfathers, Mikhail Lozinsky, was a well-known translator of the poetry of Shakespeare, Lope de Vega, and Corneille who spoke six languages fluently. He was frequently interrogated in the early 1920S for participating in the "Poets Guild" literary group; the ignorant investigator kept trying to find out where the "Guild" kept their weapons. This was under Lenin, not Stalin. His wife (my grandmother) was jailed for several months at the same time, perhaps because so many of her friends were members of the Social Revolutionary party. She later recalled that she had never before or since had such a pleasant time, or met so many intelligent and educated people. In 1921, my mother's godfather, the poet Nikolai Gumilev, was shot on a false accusation of involvement in a "monarchist plot." (There were other deaths in our family, but fewer than in some. The hatred many felt toward our family because of this was typical, and was expressed in the following way: "Why is it that they've lost so few family members?") Gumilev's wife, the famous poet Anna Akhmatova, referred to these relatively peaceful times as "vegetarian." Cannibalistic times didn't emerge out of thin air. The people willing to carry out Bolshevik orders had to ripen for the task. They matured in the murk of Russian villages, in the nightmare of factory work conditions, in the deep countryside, and in the capitals, Moscow and St. Petersburg. They were already there, there were a lot of them, and they could be counted on. "God forbid we should ever witness a Russian revolt, senseless and merciless," our brilliant poet Pushkin remarked as early as the first quarter of the nineteenth century. He knew what he was talking about. Was Lenin counting on the senselessness and mercilessness of Russians, or did he simply fail to take them into account? Whatever the case, by fate's inexorable law he, too, was victimized by his own creation: his mistress, Inessa Armand, was apparently killed; power was torn from his paralyzed hands during his lifetime; it is rumored that Stalin murdered Lenin's wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, by sending her a poisoned cake. It is merely rumored-no one knows precisely. (The vision of this rather stupid, self-assured old woman - who forbade children's stories because they were "unrealistic" but who was honest in her own way and not malicious - eating a spoonful of cake with icing and poison provokes mixed feelings in me. Mea culpa.) And how could a Russian revolt be anything but senseless and merciless, when the Russian government had exhibited a senseless lack of mercy toward its own people for centuries? From time immemorial the subjugated Russian classes have been required to inform their sovereign of anyone who for whatever reason seemed suspicious to them. From the mid-seventeenth century on, the law prescribed the death penalty for failure to report a crime committed or intended. Not only the criminal but all of his relatives must be reported. Thus, for example, since unauthorized flight abroad was considered a crime, the escapee's entire family became criminals, and death awaited them all, because it was supposed that they could not have been ignorant of the intended betrayal. Interrogation was carried out under torture, and of course everyone "confessed." The Stalinist regime didn't have to invent anything three hundred years later; it simply reproduced the political investigation techniques that were already a longstanding tradition in the Russian state. It merely included more of the population, and the pretexts for arrest became more trivial. But perhaps there was no significant difference? After all, neither the seventeenth nor the eighteenth century had their Conquest, someone to describe in scrupulous detail every aspect of what occurred. The parallels between arrests in the eighteenth century and the twentieth are so close that it's hard to shake the feeling that time has stopped. In an article by the Soviet historian Evgeny Anisimov on the history of denunciation, I read about something that happened in 1732. A man informed on a certain merchant, claiming that the merchant had called him a "traitor." The merchant was arrested (pronouncing "indecent words" was a political crime which brought suffering, torture, Siberia). With great difficulty the merchant was able to prove that the word "traitor" referred not to the other man but 1:0 a dog sitting on the porch (the merchant was speaking out loud about the fact that the dog would betray him: it would follow whoever fed it better ... ). A witness was found who confirmed that a dog actually was wandering around the porch during the conversation. This saved the merchant. Two hundred years later, in the 1930S, a herdsman was arrested and sent to the Stalinist camps for referring to a cow as a "whore" because she made advances to another cow. His crime was formulated as "slandering the communal farm herd." Of course, those who don't agree with me, who see a fundamental difference between the Russian and Soviet approaches, will say that totalitarian thinking in the Soviet period becomes all-encompassing. Previously, a dog was simply a dog, an animal; but now a cow becomes an integral part of the regime. He who affronts the cow's honor is aiming-in the final analysis- at the well-being and morals of the People. And they are also right. I only want to say that totalitarian thinking was not invented by the Soviet regime but arose in the bleak depths of Russian history, and was subsequently developed and fortified by Lenin, Stalin, and hundreds of their comrades in arms, talented students of past tyrants, sensitive sons of the people. This idea, on which I will insist, is extremely unpopular. In certain Russian circles it is considered simply obscene. Solzhenitsyn has often denounced those who think as I do; others will inevitably try to unearth my Jewish ancestors, and this explanation will pacify them. I'm speaking not only of our nationalists and fascists but about a more subtle category: those liberal Russians who forbid one to think that Russians can forbid thinking. ****** In 1953, when Stalin died, I was two years old. In one of my earliest childhood memories it is summer. There's a green lawn, bushes, and trees-and suddenly from the bushes emerge two huge people, many times greater than life size; they are wearing long white overalls, and pillows take the place of their heads; eyes and laughing mouths are drawn on the pillows. Instead of legs, they have stilts. I remember the childlike feeling of happiness and wonder, and something similar to a promise that life would contain many more such wondrous surprises. Many years later, in a chance conversation, I learned that this small group of merrymakers was imprisoned that summer for an unheard-of crime: "vulgarity." When I read The Great Terror, I carefully followed Conquest's detailed descriptions of the lengthy, notorious trials of the 1930S, the investigation of the police apparatus's cumbersome mechanisms, the network of destinies, biographies. This is all assembled into such a complex architectural edifice that I cannot help but admire the author who undertook an investigation so grandiose in scale. The reader comes away feeling that the author knows every event of the Soviet years, that no remotely accessible document has escaped his attention, that he hasn't neglected a single publication in the smallest provincial newspaper if it might throw light on one or another event. Ask him what happened to the wife of comrade X or the son of comrade Y- he knows. The only question he can't answer is: Why? Conquest does ask this question in regard to Stalin and his regime: he meticulously and wittily examines the possible motives of Stalin's behavior, both rational and irrational; he shows the deleterious effect of Bolshevik ideology on the mass consciousness, how it prepared the way for the Terror. A particularly wonderful quality of this book is also that when questions, ideas, or suppositions arise in you, the reader, the author invariably answers these mental queries a few pages later, develops the thought you've had, and figures things out along with you, bringing in more arguments on both sides than you ever thought possible. I was especially struck by this in the third chapter, ''Architect of Terror," which sketches a psychological portrait of Stalin, and in the fifth chapter, "The Problem of Confession," where Conquest explores the motivations and behavior of Stalin's victims. This book is not a storeroom of facts but a profoundly analytical investigation. Instead of getting tangled up in the abundance of information, you untangle the knots of the Soviet nightmare under the author's patient direction. Having finished this book, no one can ever again say: "I didn't know." Now we all know. But the question "Why?" remains unanswered. Perhaps the only answer is "Because." Period. My first English teacher, the daughter of Russian-Ukrainian immigrants, was once married to an American. They lived several years in America, and in the mid-1930s, like many other naive Western people who believed in socialism, they came to the USSR. They were immediately arrested and sent to prison. Her husband didn't return, but she survived. "But I'm not guilty of anything!" she screamed at the investigator. "No one here is guilty of anything," answered the exhausted investigator. "But why, then?" "Just because" was the answer. What lies behind this "Just because"? Why were two merrymakers arrested for "vulgarity"? After all, someone took the trouble to inform, someone else to listen and apprise the authorities, a third person took the trouble to be on guard, a fourth to think about it, a fifth to send an armed group to arrest them, a sixth ... and so on. Why, in a small, sleepy provincial town in the 1930S, did the head of the police, sitting on his windowsill in an unbelted shirt, waving away the flies, amuse himself by beckoning passers-by and arresting those who approached (they disappeared forever)? Why, in 1918, as the writer Ivan Bunin wrote, did peasants plundering an estate pluck the feathers off the peacocks and let them die to the accompaniment of approving laughter? Why, in 1988, in Los Angeles (I witnessed this), did a Soviet writer, in America for the first time, take in at a glance the pink, luxurious mass of a Beverly Hills hotel and daydream out loud: "Ah, they should drop a good-size bomb here"? Why, in Moscow, in our time, did a woman, upon seeing a two-year-old child sit down on the floor of a shop and refuse to get up, start yelling: "Those kinds of kids should be sent to jail! They're all bandits!"? And why did a group of women, including the sales-women and cashiers, gather around her and join in: "To jail, to jail!" they shouted. Why do Russians immediately start stamping their feet and waving their hands, hissing "Damned beast," if a cat or dog runs by? This question "Why?" has been asked by all of Russian literature, and, of course, a historian cannot answer it. He almost doesn't have the right-facts are his domain. Only some sort of blind bard, muttering poet, or absurdist playwright can answer this question. ****** In Russia, in contrast to the West, reason has traditionally been seen as a source of destruction, emotion (the soul) as one of creation. How many scornful pages have great Russian writers dedicated to Western pragmatism, materialism, rationalism! They mocked the English with their machines, the Germans with their order and precision, the French with their logic, and finally the Americans with their love of money. As a result, in Russia we have neither machines, nor order, nor logic, nor money. "We eat one another and this satisfies us." Rejecting reason, the Russian universe turns in an emotional whirlwind and can't manage to get on an even footing. Looking into the depths of Russian history, one is horrified: it's impossible to figure out when this senseless mess started. What is the source of these interminable Russian woes? The dogmatism of the Russian Orthodox Church? The Mongol invasions? The formation of the empire? Genetics? Everything together? There is no answer, or there are too many answers. You feel there's an abyss under your feet. The enslavement of the peasants, which continued for three hundred years, provoked such a feeling of guilt in the free, educated classes of Russian society that nothing disparaging could be said about the peasants. If they have certain obvious negative characteristics, then we ourselves are to blame-that is the leitmotif of the nineteenth century. All manner of extraordinary qualities-spirituality, goodness, justice, sensitivity, and charity - are ascribed to the Russian peasant and to the simple people as a whole-everything that a person longing for a normal life among normal people might hope to find. Some voices of alarm break through Russian literature, the voices of people trying to speak about the dark side of the Russian people, but they are isolated, unpopular, misinterpreted. Everyone deceives everyone else and themselves in the bargain. The revolution comes, then another, and a third-and a wave of darkness engulfs the country. The cultured classes are destroyed, the raw elements burst forth. Cultural taboos forbid us to judge "simple people" -and this is typical not only of Russia. This taboo demands that a guilty party be sought "high up." It's possible that such a search is partly justified, but, alas, it doesn't lead to anything. Once an enemy is found "up above," the natural movement is to destroy him, which is what happens during a revolution. So he's destroyed, but what has changed? Life is just as bad as ever. And people begin ever new quests for enemies, detecting them in non-Russians, in people of a different faith, and in their neighbors. But they forget to look at themselves. During Stalin's time, as I see it, Russian society, brutalized by centuries of violence, intoxicated by the feeling that everything was allowed, destroyed everything "alien": "the enemy," "minorities"-any and everything the least bit different from the "average." At first this was simple and exhilarating: the aristocracy, foreigners, ladies in hats, gentlemen in ties, everyone who wore eyeglasses, everyone who read books, everyone who spoke a literary language and showed some signs of education; then it became more and more difficult, the material for destruction began to run out, and society turned inward and began to destroy itself. Without popular support Stalin and his cannibals wouldn't have lasted for long. The executioner's genius expressed itself in his ability to feel and direct the evil forces slumbering in the people; he deftly manipulated the choice of courses, knew who should be the hors d' oeuvres, who the main course, and who should be left for dessert; he knew what honorific toasts to pronounce and what inebriating ideological cocktails to offer (now's the time to serve subtle wines to this group; later that one will get strong liquor). It is this hellish cuisine that Robert Conquest examines. And the leading character of this fundamental work, whether the author intends it or not, is not just the butcher, but all the sheep that collaborated with him, slicing and seasoning their own meat for a monstrous shish kebab. 1991 Tatyana Tolstaya: Pushkin's Children

|