|

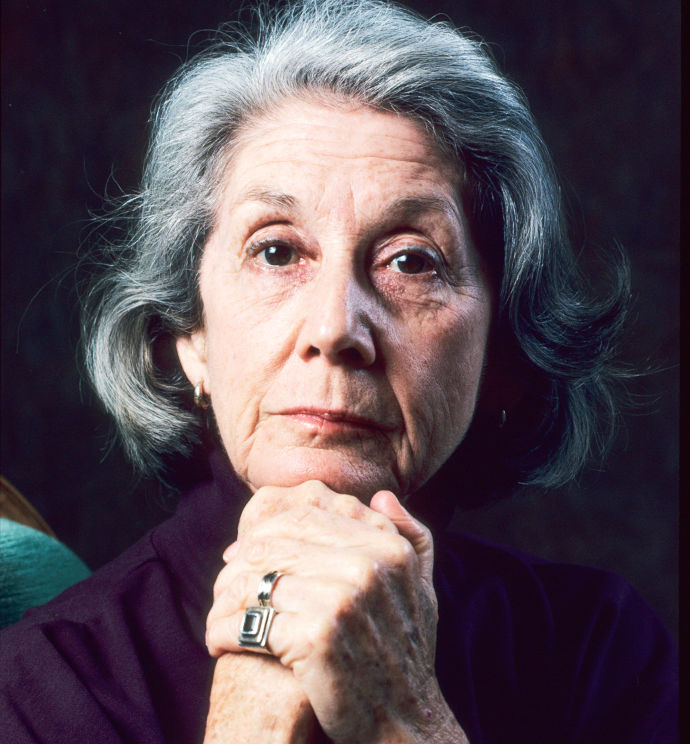

My hero: Nadine Gordimer by

Gillian Slovo JM Coetzee As a writer

and as a human being, Nadine Gordimer responded with exemplary courage

and

creative energy to the great challenge of her times, the system of

apartheid

unjustly and heartlessly imposed on the South African people. Looking

to the

great realist novelists of the 19th century as models, she produced a

body of

work in which the South Africa of the late 20th century is indelibly

recorded

for all time. She liked to say that nothing is as true as her fiction; it is certainly true that her fiction shone an unwavering light on the human suffering of apartheid. Bà thích nói, chẳng có gì thực hơn là

giả tưởng của tôi.  On Monday

morning, news came that Nadine Gordimer, who won the 1991 Nobel Prize

in

Literature, died Sunday, in Johannesburg. She was ninety years old.

Over the

decades, Gordimer wrote dozens of pieces for The New Yorker. Her first,

a short

story called “A Watcher of the Dead,” was published in 1951. After

that, she

continued to publish stories about life in South Africa, with

occasional

excursions into other genres. In 1954, she published a memoir of her

childhood,

called “Allusions in a Landscape”; in 1995, she wrote about being a

juror at

Cannes; and, in 2001, she recalled, in a short, pensive meditation on

memory,

running into an old friend on a London street. But it was

through her short fiction that Gordimer made her presence felt the

most, and

two of her short stories in our archive are available for anybody to

read. Both

happen to be about secrets revealed. “The First Sense,” from 2006, is

about a

woman who discovers that her husband, a cellist, is having an affair.

(She

works in an office; the affair is one more way in which his life is

more

exciting than hers.) “A Beneficiary,” from 2007, is about a daughter

who

discovers a family secret in her mother’s old papers. It poses a

question that

Gordimer asked in many of her stories: “How do you recognize something

that is

not in the known vocabulary of your emotions? … What do you do with

something

you’ve been told? Something that now is there in the gut of your

existence.”

It’s a theme Gordimer returned to again and again: the challenge of

responding

to the hardest facts of life. These

stories, and others by Nadine Gordimer, are available in our online

archive. Photograph

by Ulf Andersen/Getty. (1) Nghệ thuật giả tưởng Nadine Gordimer trả lời The Paris Review INTERVIEWER Chuyến đi

Anh là tìm về nguồn? Ui chao đọc,

thì liên tưởng 1 phát tới phận Gấu, cũng 1 tên Bắc Kít, cũng trở về sau

hơn nửa

thế kỷ, nhưng may mắn hơn, khác hẳn Gordimer, Gấu, lúc về thì đã có tới

hai quê

hương “thật” rồi, Nam Kít và Canada! Nadine

Gordimer, nhà văn Nam Phi đầu tiên, một trong số bẩy phụ nữ được Nobel

văn chương,

mất ngày 14 tháng Bẩy, 2014, thọ 90 tuổi. Seamus Heany, một đồng nghiệp

Nobel,

gọi bà là một trong số những “du kích lớn lao của tưởng tượng”. Con số

trên hai

chục tác phẩm [giả tưởng- tiểu thuyết, truyện ngắn] của bà, thường

xuyên

nêu lên hoàn

cảnh chính trị đa đoan, rắc rối và nhiều khi đau nhức, của mảnh đất quê

hương của

bà. Cuốn đầu, một tuyển tập truyện ngắn “Mặt nhìn Mặt”,"Face to

Face", được xb năm

1949, đúng

1 năm sau khi Nam Phi thành lập chính quyền phân biệt chủng tộc, và bà

được Nobel

năm 1991, cũng đúng 1 năm, sau khi chế độ này chấm dứt. Nghệ thuật giả tưởng Nadine Gordimer trả lời The Paris Review Nadine

Gordimer, nhà văn Nam Phi đầu tiên, một trong số bẩy phụ nữ được Nobel

văn chương,

mất ngày 14 tháng Bẩy, 2014, thọ 90 tuổi. Seamus Heany, một đồng nghiệp

Nobel,

gọi bà là một trong số những “du kích lớn lao của tưởng tượng”. Con số

trên hai

chục tác phẩm [giả tưởng- tiểu thuyết, truyện ngắn] của bà, thường

xuyên

nêu lên hoàn

cảnh chính trị đa đoan, rắc rối và nhiều khi đau nhức, của mảnh đất quê

hương của

bà. Cuốn đầu, một tuyển tập truyện ngắn “Mặt nhìn Mặt”,"Face to

Face", được xb năm

1949, đúng

1 năm sau khi Nam Phi thành lập chính quyền phân biệt chủng tộc, và bà

được Nobel

năm 1991, cũng đúng 1 năm, sau khi chế độ này chấm dứt. Obituary Nadine Gordimer Nadine

Gordimer, a South African writer and anti-apartheid advocate, died on

July

13th, aged 90 SHE had a

way of looking

at you. Even in Stockholm, in demure navy Armani, sitting on the king’s

right

at the banquet for her Nobel prize in 1991, she looked beady. Like a

bird, a

starling perhaps. Or a puffback from the South African veld, with its

loose

grey feathers and eyes of flint. Born in a

small mining

town east of Johannesburg after the Boer war, Nadine Gordimer was a

child of

empire. But there was no king and country on which to hang the family

dreams,

only South Africa. Her father, sent away from Latvia as a young

teenager by a

family that feared anti-Semitic pogroms, was ashamed of being poorly

educated.

Her middle-class English mother fretted that she had married beneath

her. Ms

Gordimer was kept at home from the age of ten, ostensibly because of a

heart

condition, but really so that her mother could call out the family

doctor, for

whom she had a weakness. Thus Ms

Gordimer’s home

life, oppressed by secrets and unspoken longings, and made liveable

only by

what she called “a certain dour

tact”, was lonely. Books became her friends. Chekhov and Dostoyevsky

taught her

the idiosyncrasies of human behaviour, Rilke filled the emptiness that

religious faith could not. Proust showed her that sexual longing, so

central to

adolescent dreams, can be as cruel as it is blissful. Yeats taught her

about

passion for justice. They all helped her make up her own mind, and

unlike many

South Africans at the time, she saw what she was looking at. Even before

the National

Party passed its apartheid laws in 1948, blacks and whites were treated

differently. That black miners pointed to items they wanted to buy from

behind

a grille, whereas she and her mother could go into a shop and try on 15

dresses, was something she never forgot. In her 20s she moved to

Johannesburg,

where she spent a year at the University of the Witwatersrand, long

enough to

make friends with blacks and with Bram Fischer (the model for the hero

of

“Burger’s Daughter”) and George Bizos, two lawyers who represented

Nelson

Mandela at the Rivonia trial where he was sentenced to life

imprisonment in

1964. Mandela became a lifelong friend: she helped edit the famous

speech that

opened his defence; he read her work in jail; and when they met again

after his

release he spoke, not of her writing or his years on Robben Island, but

of the

discovery that his wife, Winnie, had been unfaithful while he was

imprisoned. In

Johannesburg she also

discovered the intellectual energy of bohemian, black Sophiatown and,

soon

after, the freedom of being newly divorced. Sexual liberation,

especially for

women, would be a central theme of her work. She had been publishing

short

stories since she was 15 and was not yet 30 when her first novel, “The

Lying

Days”, appeared. In another

time and

another place Ms Gordimer might not have become a political writer. But

she

wrote of life around her, and the life around her was racist. Fiction,

reading

it and writing it, became synonymous with seeking truth. In 1953 the New

York Times compared “The Lying Days” with Alan Paton’s “Cry, the

Beloved

Country”, which had come out five years before, and said that her book

was “the

longer, the richer, intellectually the more exciting”. Ms

Gordimer’s first story

for the New Yorker in 1954 began the relationship that led to

her renown

outside South Africa. “Allusions in a Landscape” is a mordant tale

about a

white suburban housewife and a wacher, a Jewish watcher-over of

the

dead. There are no blacks in it, which is strange but also in a way

symbolic.

Her novels and short stories about apartheid made her famous, but her

writer’s

eye was more ambitious and far subtler than that. She could

see her way

into the lives of men and women, black and white, beyond South Africa’s

borders

to other, independent African countries; even into a post-apartheid

South

Africa when such an idea was still unthinkable for many. Seamus Heaney

called

her one of “the guerrillas of the imagination.” “The Conservationist”

won the

Booker prize in 1974. “The Lying

Days”, written

in the first person and with no plot or denouement, would hardly have

been

regarded as a novel 70 years ago, except by fans of James Joyce and

Virginia

Woolf. And yet the journey that Helen Shaw, the young white heroine,

takes into

the hovels of poor Johannesburg displays “the whole panorama of this

explosive

continent’s most explosive corner”, wrote one reviewer. Freedom

writer The arrest

of her best

friend, Bettie du Toit, and the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 sharpened

her

political courage. She joined the then-illegal African National

Congress (ANC),

and for a while she and her second husband sheltered the ANC’s

president, Albert

Luthuli, Africa’s first Nobel laureate. Three of her books were banned.

She

spoke out fiercely against censorship, both before and after apartheid

ended,

and helped found the Congress of South African Writers, to which she

gave part

of her own Nobel prize money. Prospero Guerrilla of

the imagination

Jul 15th 2014,

12:51 by E.W. NADINE

GORDIMER, the first South African and only the seventh woman to win the

Nobel

Prize for Literature, died on July 14th at the age of 90. Seamus

Heaney, a

fellow Nobel laureate, called her one of the great “guerrillas of the

imagination”. In over two dozen works of fiction, she frequently

addressed the

complex and often tormented political situation of her native land. Her

first

book, a collection of short stories called "Face to Face", was

published in 1949, just a year after the South African government

instituted

the system of apartheid. She won her Nobel Prize in 1991, the year that

system

was finally brought to an end. Along with

writers such as Alan Paton and J.M. Coetzee, hers was one of the voices

that

brought an awareness of the injustices of South African politics to the

wider

world—and her work suffered because of it. "A World of Strangers"

(1958) was banned for 12 years in her native country; "The Late

Bourgeois

World" (1966) was banned for 10 years. "Burger’s Daughter"

(1979) was also banned, but only briefly, for by that point Ms Gordimer

was an

author with a worldwide reputation. But it was not just under apartheid

that

her work was threatened: in 2001, a decade after the end of apartheid,

her 1981

novel, "July’s People"—set in a future, apocalyptic South Africa

where racial tension has erupted into full-blown civil war—was

recommended for

removal from the school curriculum in Gauteng, South Africa’s

wealthiest

province. The criticism leveled at the book was that the author did not

distance

herself strongly enough from the racism explored in the novel.

("Hamlet" was also recommended for removal because it was “not

optimistic or uplifting”.) In the end, however, the ban was not upheld. And yet in

many respects Ms Gordimer—who as a girl longed to be a ballet dancer, a

dream

destroyed because her overbearing mother believed her daughter’s health

would

suffer—never saw herself as a political writer. Her father was a Jewish

watchmaker who had come to South Africa from Lithuania as a boy; her

parents’

marriage was unhappy and she was largely self-schooled, a girl who

found

herself in books. “I would have been a writer anyway,” she told the

Paris

Review in 1983. “I was writing before politics impinged itself upon my

consciousness. In my writing, politics comes through in a didactic

fashion very

rarely…The real influence of politics on my writing is the influence of

politics on people. Their lives, and I believe their very

personalities, are

changed by the extreme political circumstances one lives under in South

Africa.” The strength

of her fiction lay in the way a social and political landscape was

expressed

through such a wide variety of characters: characters both white and

black,

characters from very different economic circumstances. The breadth of

her

imagination, and her willingness to create characters from all walks of

life,

brought criticism from those who would wish a writer of her stature to

follow a

cleanly political agenda. She answered those critics in her Nobel

lecture. “The

writer sometimes must risk both the state’s indictment of treason, and

the

liberation forces’ complaint of lack of blind commitment,” she said.

“As a

human being, no writer can stoop to the lie of Manichean ‘balance’.” In her last

book, "No Time Like the Present" (2012), her characters struggle with

the “new” South Africa, with rising crime and an inadequate education

system:

in 2006 Ms Gordimer herself became the victim of an attack, when

thieves broke

into her Johannesburg house. In her later years she lent her voice to

the

HIV/AIDS movement, campaigning for treatment for sufferers; and she

criticised

the ANC under its current leader, Jacob Zuma, expressing her opposition

to a

proposed law that would limit the publication of information deemed

“sensitive”

by the government. “The reintroduction of censorship is unthinkable

when you

think how people suffered to get rid of censorship in all its forms,”

she said

last month. But finally,

as she saw it, a writer’s task was both simple and infinitely complex:

“What a

writer does is try to make sense of life,” she said. That was something

she

always did. TV sẽ đi liền

1 đường dịch thuật.  Nadine

Gordimer, Novelist Who Took On Apartheid, Is Dead at 90 Gordimer @ TV Trong

cả ba nhà văn nổi tiếng nổi lên từ Nam Phi, chẳng có ai học xong trung

học, cả

ba đều tự học tới chỉ, và trở thành những nhà trí thức đến tận lỗ chân

lông. Điều

này cho thấy, sự quyết tâm, của những người trẻ tuổi ở mép bờ của đế

quốc, bởi

vì họ tin rằng chỉ có cách đó, mới có được cuộc sống mà họ thèm khát:

cuộc sống

của trí tưởng. (a) The function

of the writer is to act in such way that nobody can be ignorant of the

world and

that nobody may say that he is innocent of what is all about. Coetzee

trích dẫn trong bài viết về Gordimer [nhà văn Nam Phi được Nobel trước

ông],

trên tờ Điểm Sách Nữu Ước, NYRB,

số đề ngày Oct 23, 2003 In his 1988 book of essays,

“Prepared for the Worst,” Christopher

Hitchens recalled a bit of advice given to him by the South African

Nobel

Laureate Nadine Gordimer. “A serious person should try to write

posthumously,”

Hitchens said, going on to explain: “By that I took her to mean that

one should

compose as if the usual constraints—of fashion, commerce,

self-censorship,

public and, perhaps especially, intellectual opinion—did not operate.”

Hitchens’s untimely death last year, at the age of sixty-two, has

thrown this

remark into relief, pressing upon those of us who persist in writing

the

uncomfortable truth that anything we’re working on has the potential to

be

published posthumously; that death might not be far off, and that,

given this

disturbing reality, we might pay attention to it. Bài viết này quả là thần sầu!

Gấu mê quá, tính dịch hoài, rồi lại

lu bu, quên mất. Bây giờ thì lại nhớ ra, là,

Hannah Arendt cũng đã từng phán, tương

tự như Gordimer, về Walter Benjamin. Danh vọng "muộn" (posthume) - sau khi đã xuống lỗ - ít được người đời ham chuộng, tuy đây là thứ vững vàng nhất. Thứ hàng (nhà văn) có lời nhất, thì đã chết, và do đó, không phải là đồ "lạc xoong" (for sale). Trong vài món hiếm muộn, phi-thương, phi-lợi (uncommercial and unprofitable), có Walter Benjamin. (b)

This

is the text of a paper delivered at the Conference on ' Writings from

Africa: Concern and Evocation', held by the South African Indian

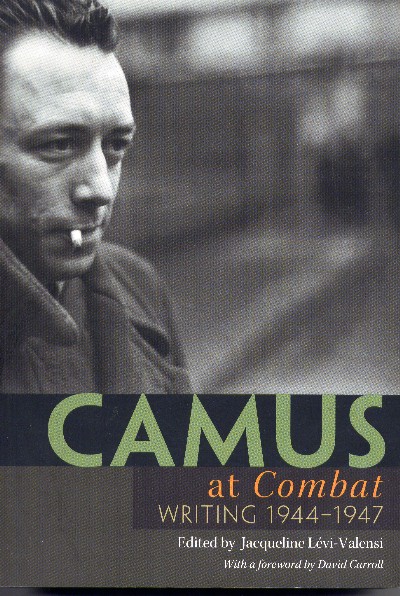

Teachers' Association in Non-fiction - Camus at

"Combat": Writing 1944-1947 by Albert Camus, edited by

Jacqueline Levi-Valensi (

|