ON REFLECTION, the habit had begun with Moishe the Beadle. It was Moishe

who led Elie Wiesel, much too young, to study Kabbalah. Most people in the

little shtetl of Sighet, in Transylvania, knew it was dangerous

even to go near those mysteries. But Moishe insisted on probing, seeking,

enquiring for deeper and deeper truths. Questions, he said, possessed power.

The more a man asked, the closer he got to God.

And why indeed had the townsfolk not asked more questions when, in 1942,

Moishe was suddenly deported? Why had they not listened to his agonised

cries of warning when he returned, weeping, knocking on doors? Why had they

insisted, even when the town was divided into two ghettos by the Nazis, that

they could live in this new world and treat it like a temporary vacation?

Why, in 1944, had they never heard the word “Auschwitz”?

As he was deported too, questions poured into Elie’s 15-year-old head.

Why were his friends and neighbours put into sealed cattle cars, to travel

for two days with almost no air or water? Why were they delivered to a place

fogged with the stench of human flesh, where pits of fire devoured the

bodies of babies and children? Why were they stripped of everything, shaved,

tattooed with numbers and made to run everywhere? Why, within a day, was

he torn from his mother and youngest sister, never to see them again? How,

in the 20th century, could such things happen, and the world stay silent?

The questions accumulated and became more disturbing. Why did fellow-inmates,

as well as Germans, beat new arrivals and call them sons of bitches? Why

did the prisoners watch the routine hangings for minor thefts without emotion,

staring indifferently at the swaying, swollen faces? Why did he find himself

thinking of nothing but his ration of soup and bread? What led him to claw

his way through a pile of dying men to save just himself? Most dreadful

of all, what led him to ignore his dying father’s request for water, when

his father was the only and dearest thing he had left in the world?

When, after a year, he was freed from the camps, he knew he had survived

to tell the tale. He must sear the memory of the Holocaust on human minds

for ever. In a world that preferred to blot it out, his motto had become

Zachor! Remember! But for a full decade he asked: How? Even as

a student of literature at the Sorbonne, even as a working journalist, how

could he find the words? What phrases could do justice to inexpressible

evil? What language could he write in, when language itself had been profaned

by obscene meanings for “selection”, “concentration”, “transport”, “chimney”

and “fire”?

Perhaps silence was a better response. Several famous rabbis had excelled

at it. After all, what authority did he have to speak for the dead, to recount

their mutilated dreams? None. But how else to remember them? For 800 pages

in Yiddish, itself a relic that had to be treasured and preserved, he poured

out his memories. Much shortened, they became “Night”, published in Engish

in 1960 and overlooked at first. He persevered. What other reason had he

to live, when six million had died? What else could be done to honour those

ghosts? In 1964 he returned to Sighet to find the town prospering but the

Jews forgotten, the closed synagogues filled with dust. He revisited the

labour camp at Buna to find it had vanished, reclaimed by trees and birds.

Who could prevent the disappearance of these things?

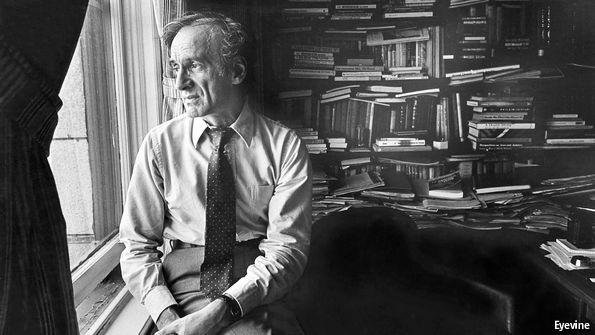

With a book every year—57 in all, each permeated by “Night”—with lectures,

articles, even cantatas, he rammed the subject of the Holocaust home. His

sad lined face, the shaggy hair, the brooding eyes, became ubiquitous where

Jewish leaders or luminaries gathered. By his 80th birthday the Holocaust

was established on modern-history curriculums, his books were on reading

lists, he had won the Nobel peace prize, and millions of visitors every

year streamed to the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, which he

had helped to found. Widening his scope beyond his beloved Israel, he set

up his own foundation to pursue human rights wherever they were threatened,

in Cambodia, Bosnia, South Africa, Chile, Rwanda. For just as he still had

nightmares of his parents and the dark, just as he still feared random

attackers and journeys by train, who was to say that the Holocaust might

not happen again?

Nor did the questions ever stop. His Talmud-studying childhood had been

devoted to God, but where had God been in the camps? Why had He allowed

Tzipora, the little golden-haired sister, to die for nothing? Why had He

caused old men to fall down from dysentery on forced marches, when they might

have died peacefully in their beds? Why had God created man, if only to

abandon him? What exactly did God need man for?

Against the melancholy that never really lifted—for how could it ever

do so?—he clung to the words “and yet”. The sun set, and yet it rose again.

Delirium struck, and yet it passed. He railed at God, and yet still strapped

on his tefillin and recited his prayers as fervently as he had

done on the day of his bar mitzvah. For ritual, too, was part of memory.

And besides, how could he ever get closer to the mystery of God, unless he

battered Him with his doubts?