|

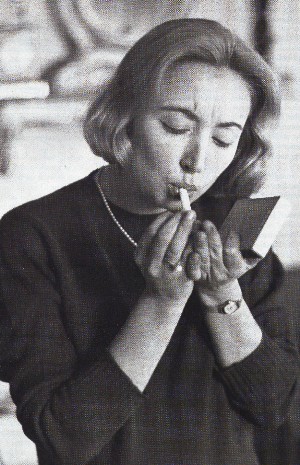

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS During the

Vietnam War, she was sometimes photographed in

fatigues and a helmet; her rucksack bore handwritten instructions to

return her

body to the Italian Ambassador “if K.I.A.” [killed in action].

In these

images she looked as slight and vulnerable as a child. [The

New Yorker]

Trong Cuộc

Chiến Việt Nam, những bức hình của bà đôi khi lộ vẻ mệt mỏi,

với cái nón sắt, chiếc ba lô, và với những dòng di chúc viết tay: Xin

đưa xác tôi tới Toà Đại Sứ Ý, nếu tôi bị giết trong khi hành nghề ký

giả. Trong những bức hình như thế trông bà chẳng khác gì một đứa bé,

rất dễ bị thương tổn.

*

DTH: The Trouble Maker

Còn dưới đây là chân dung của The Agitator: Oriana Fallaci  Fallaci in

"Whether it

comes from a

despotic

sovereign or an

elected president, from a murderous general or a beloved leader, I see

power as

an inhuman and hateful phenomenon.... I have always looked on

disobedience

toward the oppressive as the only way to use the miracle of having been

born."[Sự thông minh quá quắt, quỷ quyệt, thói hung hăng con bọ xít - cộng vẻ nhìn thật dễ ưa, và cái thói nịnh đầm của Âu Châu - đã làm bà trở thành một phỏng vấn gia đệ nhất hạng, đếch có ai sánh bằng] Nguồn [Người Nữu Ước số đề ngày 5 Tháng Sáu 2006] Kissinger đã từng than, đó là cuộc nói chuyện thê thảm nhất mà tôi đã ngu si dính vô, [ngu si, vì Vua Đi Đêm bị phỉnh, là bài phỏng vấn sẽ được đem vô đền thờ những vị thần của giới báo chí]. “Bất kể là thằng cha nào, cho dù Tổng Bí Thư hay Tổng Thống do dân bầu, cho dù Tướng Sát Nhân hay Nhà Lãnh Đạo Đáng Yêu, Người Cầm Lái Vĩ Đại, Cha Già Dân Tộc.... tôi đều tởm, như tởm quyền lực, một thứ bất nhân đáng ghét. Tôi luôn nhìn kẻ áp bức, thằng có quyền, bằng cái nhìn không thân thiện, như thế đó, và coi đây là cách độc nhất để sử dụng tới phép lạ, là được sinh ra ở trên cõi đời này.” Và tất nhiên, nếu mắc ỉa, thì ị ngay vào mặt chúng! Lần đầu Gấu đọc Fallaci, là lần Bà phỏng vấn tướng độc nhãn Do Thái. Bà hỏi, có phải Do Thái là đồ chơi, búp bế, tà lọt... của Mẽo? Ông này điên lên, sủa liền, Bà có thấy cảnh quan thầy bỏ chạy khỏi Việt Nam trên đỉnh tòa nhà Sài Gòn? Do Thái chúng tôi, từ khi lập nước, chưa hề gặp cảnh nhục nhã như thế. Làm sao thứ khốn nạn đó lại là sư phụ của chúng tôi? Nhật Ký Tin Văn 40 * The Rage and The Pride Oriana Fallaci: Will Chairman Mao's portrait above Tiananmen Gate be kept there? Deng Xiaoping: It will, forever. In the past there were too many portraits of Chairman Mao. They were hung everywhere Phỏng vấn Đặng Tiểu Bình Bức hình Mao Xếng Xáng vưỡn cứ hơi bị được treo ở Thiên An Môn, như chuyện thường ngày ở huyện chứ? Tại sao không? Trước đây, chỗ nào mà không có hình Mao Xếnh Xáng? INSHALLAH By Oriana Fallaci * Có vài ý kiến cùng Ông trong đoạn viết về Fallaci Combative: dịch là hung hăng, hay cãi cọ thì gần hơn. (Eager or disposed to fight; belligerent. See synonyms at argumentative.) Chic: Không phải là thói nịnh đầm mà là hợp thời trang 1 cách lịch sự. (Adopting or setting current fashions and styles. See synonyms at fashionable.) Chuyện nhỏ thôi. Kính. Cám ơn bạn. Trân trọng. NQT TB: Tôi tra từ điển Cassell. Combative: inclined to combat: Nghiêng về uýnh lộn. Gửi thêm bài ai điếu trên Người Kinh Tế. Báo này dùng những từ mạnh hơn: Fighter, Tiger. Kính. NQT  Người Kinh Tế 23 Tháng Chín, 2006  Báo Time

Thực tình mà nói, một cái tít

như là Người

phỏng vấn tướng Giáp đã qua đời, ở một nơi chốn như Bi Bì Xèo,

làm người nghe/đọc không thể nào không có ý nghĩ, đây là một cách nâng

bi mấy anh VC.

Tít như thế chưa đủ đô, còn tố thêm, bằng những dòng 'uy tín nhất' (1, sau đây nữa chớ: Trong sự nghiệp báo chí, bà đã có nhiều cuộc phỏng vấn với các nhân vật nổi tiếng, từ Đại tướng Võ Nguyên Giáp, Tổng thống Nguyễn Văn Thiệu đến Henry Kissinger, Ali Bhutto, Indira Gandhi và Đặng Tiểu Bình. * Hãy coi cách loan tin của Time, mà học hỏi. Đồng ý, đây là một bản tin tiếng Việt, cho người Việt. Nhưng một cái tít như thế, chỉ có thể đăng trên một tờ báo ở trong nước. Gấu thực sự tin rằng, tay nào làm tin này, đã từng làm cho Đài Hà Nội! NQT * (1) Chữ của NMG: 1. Bây giờ điểm lại người có uy tín nhất hiện nay là Nguyễn Hưng Quốc, tiếp theo là Đặng Tiến, Bùi Vĩnh Phúc, Thụy Khuê, Trần Hữu Thục, Nguyễn Vy Khanh... và một vài người khác nữa. 2. Khi kê khai mà thiếu bất kỳ ai thì chết với họ. Có khi kể họ sau người khác cũng không được. Mà chẳng lẽ kê khai đồng hạng cả thì cũng không được. * Thưa Giáo Chủ, làm thế nào mà Ngài bơi được, trong chiếc áo choàng?. Câu hỏi thật là đểu của Fallaci, với Khomeini làm Gấu nhớ một giai thoại về Nguyễn Tuân: Mặc áo gấm, nhẩy xuống sông, thi bơi. Nhưng câu này thì thật là tuyệt: Chẳng có chi lột trần con người như cái kiểu chiến tranh lột trần. Nothing reveals man the way war does. Câu này đẻ ra câu sau: Chỉ ở trong tù, nhất là tù cải tạo, không có án, chẳng biết khi nào được về, thì mới biết được giá trị của con người. Thực tình mà nói, một cái tít như là Người phỏng vấn tướng Giáp đã qua đời, ở một nơi chốn như Bi Bì Xèo, làm người nghe/đọc không thể nào không có ý nghĩ, đây là một cách nâng bi mấy anh VC. Tít như thế chưa đủ đô, còn tố thêm, bằng những dòng 'uy tín nhất' sau đây nữa chớ: Trong sự nghiệp báo chí, bà đã có nhiều cuộc phỏng vấn với các nhân vật nổi tiếng, từ Đại tướng Võ Nguyên Giáp, Tổng thống Nguyễn Văn Thiệu đến Henry Kissinger, Ali Bhutto, Indira Gandhi và Đặng Tiểu Bình. * Nhưng đâu chỉ Fallaci phỏng vấn Đại Tướng Võ Nguyên Giáp. Như Đại tướng Võ Nguyên Giáp đã từng nói với tôi [Karnow], vào năm 1990 tại Hà Nội, điều quan tâm chính của ông ta, là chiến thắng. Khi tôi hỏi, bao lâu, "Hai chục năm, có thể 100 năm - lâu cỡ nào cũng được, chết bao nhiêu cũng được", ["Twenty years, maybe 100 years - as long as it took to win - regardless of cost"]. Con số người chết thật là khủng khiếp. Chừng ba triệu người hai miền, cả binh sĩ và thường dân. Sinh Nhạt Bác: Đi tìm một cái nón cối đã mất. Giá mà kiếm được cú phỏng vấn tướng Giáp của người đã qua đời Fallaci, chắc là còn nhiều chi tiết quái dị lắm. Liệu Fallaci có biết tướng Giáp đã từng lo chuyện sinh đẻ? Cái gì gì "Ngày xưa Đại tướng công đồn, bi giờ Đại Tướng...", "Ngày xưa Đại Tướng cầm quân, Bi giờ Đại Tướng cầm quần chị em"! In 1969, General Vo Nguyen Giap admitted in an interview with Oriana Fallaci, an Italian reporter, that his Vietnamese Communist forces had lost half million men. But recently, [Vào năm 1969 tướng Giáp thừa nhận với Fallaci, VC mất nửa triệu, nhưng mới đây, VC nói lại, mất 1,100,000]. Nguồn * Cái tít rất quan trọng. Một trong những cách nói về mình. Đọc cái tít, người ta đoán ngay ra tẩy của bạn. Nhà văn Norman Manea, cũng thuộc loại chạy trốn quê hương, kể kinh nghiệm, một lần ông mở một khóa học ở Mẽo, với cái tít là: "Danube: A Literary Journey", Danube, một chuyến đi văn học, gồm một số nhà văn như Kafka, Ionesco, Danilo Kis, vv.. Đếch có một sinh viên nào thèm ghi danh! Lạ quá, ông xin ý kiến đồng nghiệp. Họ bèn lôi ông về với thực tại [One of them tried to wake me up to reality]: "Lỗi của anh ở ngay cái tít: Danube. Danube là cái đếch gì?" "Bạn nên đặt là, thí dụ: "Kafka Giết Cha Mình"." Hiện nay, tôi đang dậy một khóa, "Kafka và Láng Giềng", trong có mấy ông như Schulz, Musil, Ionesco, Joseph Roth. Rất đông sinh viên tham dự! Lần đầu Gấu viết bài cho một diễn đàn bạn. Cái tít dài thòng. Bà chủ quán cười, nói, để 'thiến' bớt. (1) Còn đúng ba chữ: Dịch Là Cướp. Tuyệt cú mèo! (1) Từ trước, đã đọc NQT, nhưng chưa bao giờ thấy tức cười như bài này. Đây là một khía cạnh mới, của... Gấu? [Trích mail riêng]. Một bạn văn, thuộc loại trẻ, ngoài nước, viết thường trực cho VHNT [hồi còn sống], mail: Chưa từng thấy bài nào tức cười như bài này, nhất là cái chi tiết nhét hột ngô vào đúng chỗ chuyên làm giống để mang về làm giống cho cả một dân tộc. Thú thật ! NQT * Theo tôi, dịch là cướp. Nếu không cướp được thì ăn cắp, như trường hợp một ông trạng đi xứ nhét hột ngô Tầu vào bìu khi qua ải Nam Quan, đem về Việt Nam làm giống. Dịch Là Cướp * Cái tít này, của bà chủ quán, mà chả 'tuyệt cú mèo'? Miếng Cơm, Manh Chữ To the Italian reporter, Ms. Orion Fallaci in an interview in February 1969, when she asked him about how 45,000 soldiers dead, he said, "Every two minutes, three hundred thousand people die on this planet. What are forty-five thousand for a battle? In war death doesn't count." Despite the objectives of a war, good or bad, a commander of an armed force cannot be a military genius if he hold the life of his soldier so cheap as if it were money that can be paid to win a battle at any price. In the above-mentioned interview, when Ms. Fallaci asked him whether he thought the Tet Offensive was a failure, Giap said, "Tell that to, or rather ask, the Liberation Front." He explained it was a delicate question that he couldn't express judgments, that he wouldn't meddle in the affairs of the Front. He also said, "I won't discuss the Tet offensive, which didn't depend on me, didn't depend on us; it was conducted by the Front." The interview thus revealed some of Giap's personality. First of all, everybody knows for certain that during the war, all major campaigns in Some reliable sources in He has lost his comrades' trust since. But it was in 1979, after the Vietnam Communist forces overthrew Khmer Rouge regime and occupied According to the same sources, once again in a secret meeting of the Politburo about the campaign to liberate This time the supreme ruling body did not tolerate him and Giap was ousted from the Politburo. His status of the top leader was revoked. Later he was appointed president of the National Family Planning Committee, a job that brought Cái tít rất quan trọng. Một trong những cách nói về mình. Đọc cái tít, người ta đoán ngay ra tẩy của bạn. Nhà văn Norman Manea, cũng thuộc loại chạy trốn quê hương, kể kinh nghiệm, một lần ông mở một khóa học ở Mẽo, với cái tít là: "Danube: A Literary Journey", Danube, một chuyến đi văn học, gồm một số nhà văn như Kafka, Ionesco, Danilo Kis, vv.. Đếch có một sinh viên nào thèm ghi danh! Lạ quá, ông xin ý kiến đồng nghiệp. Họ bèn lôi ông về với thực tại [One of them tried to wake me up to reality]: "Lỗi của anh ở ngay cái tít: Danube. Danube là cái đếch gì?" "Bạn nên đặt là, thí dụ: "Kafka Giết Cha Mình"." Hiện nay, tôi đang dậy một khóa, "Kafka và Láng Giềng", trong có mấy ông như Schulz, Musil, Ionesco, Joseph Roth. Rất đông sinh viên tham dự! Lần đầu Gấu viết bài cho một diễn đàn bạn. Cái tít dài thòng. Bà chủ quán cười, nói, để 'thiến' bớt. (1) Còn đúng ba chữ: Dịch Là Cướp. Tuyệt cú mèo! (1) Từ trước, đã đọc NQT, nhưng chưa bao giờ thấy tức cười như bài này. Đây là một khía cạnh mới, của... Gấu? [Trích mail riêng]. Một bạn văn, thuộc loại trẻ, ngoài nước, viết thường trực cho VHNT [hồi còn sống], mail: Chưa từng thấy bài nào tức cười như bài này, nhất là cái chi tiết nhét hột ngô vào đúng chỗ chuyên làm giống để mang về làm giống cho cả một dân tộc. Thú thật ! NQT * Theo tôi, dịch là cướp. Nếu không cướp được thì ăn cắp, như trường hợp một ông trạng đi xứ nhét hột ngô Tầu vào bìu khi qua ải Nam Quan, đem về Việt Nam làm giống. Dịch Là Cướp * Cái tít này, của bà chủ quán, mà chả 'tuyệt cú mèo' sao? Miếng Cơm, Manh Chữ * Nhân nói chuyện cái tít, gặp liền một cái tít khó nhai: Les Bienveillantes. Nghĩa đen, những người đàn bà khoan dung, nhân từ. Nhưng, nó còn là lối nói trại của từ Furies, còn gọi là Erinyes [Furies là cách gọi của người La Mã]. Như thế, đây là sự nhập thân vào người đàn bà của sự trả thù [female personifications of vengeance]. Oriana Fallaci directs her

fury toward Islam.by Margaret Talbot The New Yorker “Yesterday,

I was hysterical,” the Italian

journalist and novelist Oriana Fallaci said. She was telling me a story

about a

local dog owner and the liberties he’d allowed his animal to take in

front of

Fallaci’s town house, on the Upper East Side. Big mistake. “I no longer

have

the energy to get really angry, like I used to,” she added. It called

to mind

what the journalist Robert Scheer said about Fallaci after interviewing

her for

Playboy, in 1981: “For the first time in my life, I found myself

feeling sorry

for the likes of Khomeini, Qaddafi, the Shah of Iran, and Kissinger—all

of whom

had been the objects of her wrath—the people she described as

interviewing

‘with a thousand feelings of rage.’ ” For two

decades, from the mid-nineteen-sixties to the mid-nineteen-eighties,

Fallaci

was one of the sharpest political interviewers in the world. Her

subjects were

among the world’s most powerful figures: Yasir Arafat, Golda Meir,

Indira

Gandhi, Haile Selassie, Deng Xiaoping. Henry Kissinger, who later wrote

that

his 1972 interview with her was “the single most disastrous

conversation I have

ever had with any member of the press,” said that he had been flattered

into

granting it by the company he’d be keeping as part of Fallaci’s

“journalistic

pantheon.” It was more like a collection of pelts: Fallaci never left

her

subjects unskinned. Fallaci’s

manner of interviewing was deliberately unsettling: she approached each

encounter with studied aggressiveness, made frequent nods to European

existentialism (she often disarmed her subjects with bald questions

about

death, God, and pity), and displayed a sinuous, crafty intelligence. It

didn’t

hurt that she was petite and beautiful, with straight, smooth hair that

she

wore parted in the middle or in pigtails; melancholy blue-gray eyes,

set off by

eyeliner; a cigarette-cured voice; and an adorable Italian accent.

During the

Vietnam War, she was sometimes photographed in fatigues and a helmet;

her

rucksack bore handwritten instructions to return her body to the

Italian

Ambassador “if K.I.A.” In these images she looked as slight and

vulnerable as a

child. When she was shot, in 1968, while reporting on the student

demonstrations in Mexico City, and then confined by the police with the

wounded

and the dying on one floor of an apartment building, the first impulse

of the

students around her was to protect her; one boy gave her his sweater,

in order

to cover her face from the drip of a sewage pipe. Her essential

toughness never

stopped taking people—men, especially—by surprise. Fallaci’s

journalism, at first conducted for the Italian magazine L’Europeo and

later

published in translation throughout the world, was infused with a

“mythic sense

of political evil,” as the writer Vivian Gornick once put it—an almost

adolescent aversion to power, which suited the temperament of the

times. As

Fallaci explained in her preface to “Interview with History,” a 1976

collection

of Q. & A.s, “Whether it comes from a despotic sovereign or an

elected

president, from a murderous general or a beloved leader, I see power as

an

inhuman and hateful phenomenon. . . . I have always looked on

disobedience

toward the oppressive as the only way to use the miracle of having been

born.”

In Fallaci’s interview with Kissinger, she told him that he had become

known as

“Nixon’s mental wet nurse,” and lured him into boasting that Americans

admired

him because he “always acted alone”—like “the cowboy who leads the

wagon train

by riding ahead alone on his horse, the cowboy who rides all alone into

the

town.” Political cartoonists mercilessly lampooned this remark, and,

according

to Kissinger’s memoirs, the quote soured his relations with Nixon.

(Kissinger

claimed that she had taken his words out of context.) But the most

remarkable

moment in the interview came when Fallaci bluntly asked him, about

Vietnam,

“Don’t you find, Dr. Kissinger, that it’s been a useless war?,” and

Kissinger

began his reply with the words “On this, I can agree.” from the

issuecartoon banke-mail this.Fallaci’s interview with Khomeini, which

appeared

in the Times on October 7, 1979, soon after the Iranian revolution, was

the

most exhilarating example of her pugilistic approach. Fallaci had

travelled to

Qum to try to secure an interview with Khomeini, and she waited ten

days before

he received her. She had followed instructions from the new Islamist

regime,

and arrived at the Ayatollah’s home barefoot and wrapped in a chador.

Almost

immediately, she unleashed a barrage of questions about the closing of

opposition newspapers, the treatment of Iran’s Kurdish minority, and

the

summary executions performed by the new regime. When Khomeini defended

these

practices, noting that some of the people killed had been brutal

servants of

the Shah, Fallaci demanded, “Is it right to shoot the poor prostitute

or a

woman who is unfaithful to her husband, or a man who loves another

man?” The

Ayatollah answered with a pair of remorseless metaphors. “If your

finger

suffers from gangrene, what do you do? Do you let the whole hand, and

then the

body, become filled with gangrene, or do you cut the finger off? What

brings

corruption to an entire country and its people must be pulled up like

the weeds

that infest a field of wheat.” Fallaci

continued posing indignant questions about the treatment of women in

the new

Islamic state. Why, she asked, did Khomeini compel women to “hide

themselves,

all bundled up,” when they had proved their equal stature by helping to

bring

about the Islamic revolution? Khomeini replied that the women who

“contributed

to the revolution were, and are, women with the Islamic dress”; they

weren’t

women like Fallaci, who “go around all uncovered, dragging behind them

a tail

of men.” A few minutes later, Fallaci asked a more insolent question:

“How do

you swim in a chador?” Khomeini snapped, “Our customs are none of your

business. If you do not like Islamic dress you are not obliged to wear

it.

Because Islamic dress is for good and proper young women.” Fallaci saw

an

opening, and charged in. “That’s very kind of you, Imam. And since you

said so,

I’m going to take off this stupid, medieval rag right now.” She yanked

off her

chador. In a recent

e-mail, Fallaci said of Khomeini, “At that point, it was he who acted

offended.

He got up like a cat, as agile as a cat, an agility I would never

expect in a

man as old as he was, and he left me. In fact, I had to wait for

twenty-four

hours (or forty-eight?) to see him again and conclude the interview.”

When

Khomeini let her return, his son Ahmed gave Fallaci some advice: his

father was

still very angry, so she’d better not even mention the word “chador.”

Fallaci

turned the tape recorder back on and immediately revisited the subject.

“First

he looked at me in astonishment,” she said. “Total astonishment. Then

his lips

moved in a shadow of a smile. Then the shadow of a smile became a real

smile.

And finally it became a laugh. He laughed, yes. And, when the interview

was

over, Ahmed whispered to me, ‘Believe me, I never saw my father laugh.

I think

you are the only person in this world who made him laugh.’ ” Fallaci

recalled that she found Khomeini intelligent, and “the most handsome

old man I

had ever met in my life. He resembled the ‘Moses’ sculpted by

Michelangelo.”

And, she said, Khomeini was “not a puppet like Arafat or Qaddafi or the

many

other dictators I met in the Islamic world. He was a sort of Pope, a

sort of

king—a real leader. And it did not take long to realize that in spite

of his

quiet appearance he represented the Robespierre or the Lenin of

something which

would go very far and would poison the world. People loved him too

much. They

saw in him another Prophet. Worse: a God.” Upon leaving

Khomeini’s house after her first interview, Fallaci was besieged by

Iranians

who wanted to touch her because she’d been in the Ayatollah’s presence.

“The

sleeves of my shirt were all torn off, my slacks, too,” she recalled.

“My arms

were full of bruises, and hands, too. Do believe me: everything started

with

Khomeini. Without Khomeini, we would not be where we are. What a pity

that,

when pregnant with him, his mother did not choose to have an abortion.” Today,

Fallaci believes, the Western world is in danger of being engulfed by

radical

Islam. Since September 11, 2001, she has written three short, angry

books

advancing this argument. Two of them, “The Rage and the Pride” and “The

Force

of Reason,” have been translated into idiosyncratic English by Fallaci

herself.

(She has had difficult relationships with translators in the past.) A

third,

“The Apocalypse,” was recently published in Europe, in a volume that

also

includes a lengthy self-interview. She writes that Muslim immigration

is

turning Europe into “a colony of Islam,” an abject place that she calls

“Eurabia,” which will soon “end up with minarets in place of the

bell-towers,

with the burka in place of the mini-skirt.” Fallaci argues that Islam

has

always had designs on Europe, invoking the siege of Constantinople in

the

seventh century, and the brutal incursions of the Ottoman Empire in the

fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. She contends that contemporary

immigration

from Muslim countries to Europe amounts to the same thing—invasion—only

this

time with “children and boats” instead of “troops and cannons.” And, as

Fallaci

sees it, the “art of invading and conquering and subjugating” is “the

only art

at which the sons of Allah have always excelled.” Italy, unlike

America, has

never been a melting pot, or a “mosaic of diversities glued together by

a

citizenship. Because our cultural identity has been well defined for

thousands

of years we cannot bear a migratory wave of people who have nothing to

do with

us . . . who, on the contrary, aim to absorb us.” Muslim

immigrants—with their

burkas, their chadors, their separate schools—have no desire to

assimilate, she

believes. And European leaders, in their muddleheaded multiculturalism,

have

made absurd accommodations to them: allowing Muslim women to be

photographed

for identity documents with their heads covered; looking the other way

when

Muslim men violate the law by taking multiple wives or defend the abuse

of

women on supposedly Islamic grounds. (European governments are, in

fact,

hardening on these matters: France recently deported a Muslim cleric in

Lyons

who advocated wife-beating and the stoning of adulterous women.) According to

Fallaci, Europeans, particularly those on the political left, subject

people

who criticize Muslim customs to a double standard. “If you speak your

mind on

the Vatican, on the Catholic Church, on the Pope, on the Virgin Mary or

Jesus

or the saints, nobody touches your ‘right of thought and expression.’

But if

you do the same with Islam, the Koran, the Prophet Muhammad, some son

of Allah,

you are called a xenophobic blasphemer who has committed an act of

racial

discrimination. If you kick the ass of a Chinese or an Eskimo or a

Norwegian

who has hissed at you an obscenity, nothing happens. On the contrary,

you get a

‘Well done, good for you.’ But if under the same circumstances you kick

the ass

of an Algerian or a Moroccan or a Nigerian or a Sudanese, you get

lynched.” The

rhetoric of Fallaci’s trilogy is intentionally intemperate and

frequently

offensive: in the first volume, she writes that Muslims “breed like

rats”; in

the second, she writes that this statement was “a little brutal” but

“indisputably accurate.” She ascribes behavior to bloodlines—Spain, she

writes,

has been overly acquiescent to Muslim immigrants because “too many

Spaniards

still have the Koran in the blood”—and her political views are often

expressed

in the language of disgust. Images of soiling recur in the books: at

one point

in “The Rage and the Pride” she complains about Somali Muslims leaving

“yellow

streaks of urine that profaned the millenary marbles of the Baptistery”

in

Florence. “Good Heavens!” she writes. “They really take long shots,

these sons

of Allah! How could they succeed in hitting so well that target

protected by a

balcony and more than two yards distant from their urinary apparatus?”

Six

pages later, she describes urine streaks in the Piazza San Marco, in

Venice,

and wonders if Muslim men will one day “shit in the Sistine Chapel.” These books

have brought Fallaci, who will turn seventy-seven later this month, and

who has

had cancer for more than a decade, to a strange place in her life. Much

of the

Italian intelligentsia now shuns her. (The German press has been highly

critical, too.) A 2003 article in the left-wing newspaper La Repubblica

called her

“ignorantissima,” an “exhibitionist posing as the Joan of Arc of the

West.” A

fashionable gallery in Milan recently showed a large portrait of

her—beheaded.

After the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera published the long

article that

became “The Rage and the Pride,” La Repubblica ran a reply from Umberto

Eco,

which did not mention Fallaci by name but denounced cultural chauvinism

and

called for tolerance. “We are a pluralistic society because we permit

mosques

to be built in our own home, and we cannot give this up just because in

Kabul

they put evangelical Christians in jail,” he wrote. “If we did, we

would become

Taliban ourselves.” Fallaci has

repeatedly fallen afoul of some of Europe’s strict laws against

vilifying

religions or inciting racial hatred. (In Europe, the prevailing impulse

toward

certain kinds of outré opinions is to ban their expression.) In 2002, a

French

group, Movement Against Racism and for Friendship Between Peoples,

tried

unsuccessfully to get “The Rage and the Pride” banned. The following

year,

Swiss officials, under pressure from Muslim groups in that country,

asked that

she be extradited for trial; the Italian Minister of Justice refused

the

request. And she currently faces trial in Italy, on charges that amount

to

blasphemy, of all things. Last year, Adel Smith, a convert to Islam who

heads a

group called the Muslim Union of Italy, and who had previously sued the

government to have a crucifix removed from his sons’ classroom,

persuaded a

judge in Bergamo to allow him to charge Fallaci with defaming Islam. A

Mussolini-era criminal code holds that “whoever offends the state’s

religion,

by defaming those who profess it, will be punished with up to two years

of

imprisonment.” Though the code was written to protect the Catholic

Church, it

has been successively amended in the past ten years, so that it

encompasses any

“religion acknowledged by the state.” The complaint against Fallaci

marks the

first time that the code has been invoked on behalf of any religion but

Catholicism. (In January, Fallaci’s supporters in the Italian Senate

pushed

through an amendment to the code, reducing the maximum penalty to five

thousand

euros.) Yet

Fallaci’s recent books, and the specious trial that she is facing as a

result—her books may offend, but it is no less offensive to prosecute

her for

them—have also made her a beloved figure to many Europeans. The books

have been

best-sellers in Italy; together they have sold four million copies. To

her

admirers, she is an aging Cassandra, summoning her strength for one

final

prophecy. In September, she had a private audience with Pope Benedict

XVI at

Castel Gandolfo, his summer residence outside Rome. She had criticized

John

Paul II for making overtures to Muslims, and for not condemning

terrorism

heartily enough, but she has hopes for Joseph Ratzinger. (The meeting

was

something of a scandal in Italy, since Fallaci has always said that she

is an

atheist; more recently, she has called herself a “Christian atheist,”

out of

respect for Italy’s Catholic tradition.) Last December, the Italian

government

presented her with a gold medal for “cultural achievement.” Fallaci’s

arguments appeal to many Europeans on a visceral level. The murder of

the Dutch

filmmaker Theo van Gogh, the “honor killings” of young women in England

and

Sweden, and the controversy in France over whether girls may wear head

scarves

to school have underscored the enormous clash in values between secular

Europeans and fundamentalist Muslim immigrants. In Holland, immigration

officials have begun showing potential immigrants films and brochures

that

detail certain “European” values, including equality of the sexes and

tolerance

of homosexuality. The implicit suggestion is that in order to live in

Europe

you must accept these ideas. Such clumsy efforts betray the frustration

and

confusion that many Europeans have felt since the riots that broke out

in the

suburbs of Paris last fall—perhaps the most spectacular sign that the

assimilation of Western Europe’s fifteen million Muslims has stalled in

many

places, and never started in others. Some

European intellectuals have given Fallaci credit for offering an

enraged,

articulate voice to people who are genuinely bewildered and dismayed by

the

challenges of assimilating Islamic immigrants. In 2002, writing in the

Italian

weekly Panorama, Lucia Annunziata, a former foreign correspondent and

columnist, and Carlo Rossella, then the magazine’s editor, argued that

“The

Rage and the Pride” had “redefined Italy’s conception of the current

conflict

between the Western world and the Islamic world. . . . Oriana Fallaci

has

confronted the issue with ironclad simplicity: We are different, she

has said.

And, at this point, we are incompatible.” The French philosopher Alain

Finkielkraut, writing in Le Point, said that Fallaci “went too far,”

reducing

all “Sons of Allah to their worst elements,” yet he commended her for

taking

“the discourse and the actions of our adversaries” at their word and—in

the

wake of September 11th, the execution of Daniel Pearl, the destruction

of

Buddhas in Afghanistan, and other atrocities committed in the name of

Islam—not

being intimidated by the “penitential narcissism that makes the West

guilty of

even that which victimizes it.” Last year, a

support committee for Fallaci collected some letters that it had

received from

people across Italy and presented them as a testimonial to her. A

Florentine

couple wrote, “Brava, Oriana. You had the courage and the pride to

speak in the

name of most Italians (who are perhaps too silent) who still have not

sold out

the social, moral, and religious values that belong to us. . . . If

[immigrants] do not share our ideas, then why do they come to Italy?

Why should

we endure arrogance and interference by those who have no desire to

integrate

into our system and who are darkened by anti-Western hatred? We welcome

them as

guests, but immediately they act like the owners.” Another fan wrote,

“In this

tragic and historic moment, only one voice has been raised high to

speak for

the conscience of most Westerners. . . . That is why we are impotently

witnessing the breakdown and decline of a civilization whose values are

now

ridiculed by those who are in charge of protecting them. . . . Thank

you,

Oriana.” Fallaci owns

an apartment in Florence and has an estate in the Tuscan countryside.

But she

spends most of the year in New York, where she leads a fairly solitary

life

and, necessarily, spends a lot of time visiting doctors. In November,

when she

delivered an acceptance speech for an award given by the conservative

Center

for the Study of Popular Culture, it was a rare public appearance. “Darling,”

she growled over the phone the first time we spoke, “as you well know,

I never

give interviews.” Strictly speaking, this isn’t true. Over the years,

she’s

given many of them, sometimes with embarrassing results—in Scheer’s

1981

Playboy interview, she complained about homosexuals who “swagger and

strut and

wag their tails” and “fat” women reporters who didn’t like her. When I

visited

her on a rainy Saturday afternoon in April, and again the next day, I

found her

voluble and dramatic, capable of leaping to her feet to illustrate a

point, and

shouting when she felt the point warranted it—which was often. She

smoked

little brown Nat Sherman cigarettes; smoking, she believes,

“disinfects” her. Fallaci’s

New York residence is a handsome nineteenth-century brownstone, painted

white,

with a walled garden in the back. She had longed for such a house since

childhood; as a young girl in Italy during the Second World War, she’d

found a

Collier’s magazine in a care package dropped by U.S. military pilots,

and

fallen in love with a photo essay about American houses. “It’s funny to

say

that, with the marvellous architecture we have in Italy, I desired a

house like

this,” she said. “I grew up with this obsession of a white house with a

black

door.” Inside, the second-floor rooms, where we talked, had a

scholarly,

slightly worn elegance. The bookshelves held translations of Fallaci’s

books

and leather-bound early editions of Dickens, Voltaire, and Shakespeare.

There

were eighteenth- and nineteenth-century oil paintings on the walls; an

old-fashioned cream-colored dial phone sat on a small table with a

stained-glass

lamp. It was the sort of setting where you could imagine retired

professors

sipping port and sparring genially over Greek participles. It was not

the sort

of setting where you expected to find a woman of Fallaci’s age yelling

“Mamma

mia! ” and threatening to break various people’s heads and blow things

up. We sat down

next to a table piled with newspaper clippings from Italy, which

chronicled

Fallaci’s anti-Islamic crusade: articles by her and articles about her,

often

on the front page. The Italian press is, as she puts it, “ob-sess-ed”

with her.

One article, “Reading Oriana in Tehran,” which had run in La Stampa,

claimed

that Fallaci was a legend among independent-minded women in Iran.

“That’s damn

good!” she said. Fallaci’s earlier books are widely available in Iran,

but the

trilogy has been banned. “You know what these women did?” she said.

“They got

copies in English and in French, and they photocopied them, chapter by

chapter,

and distributed them to others. They can go to jail for that.” The

reporter for

La Stampa had mainly found women who admired Fallaci for her earlier

work: two

female university students noted that Fallaci had been equally tough on

the

Shah and on Khomeini, and that she’d shown up to get her Iranian visa

wearing

nail polish and jeans. On the day I

visited, Fallaci was dressed like a refined European lady: tweed skirt,

leaf-green sweater, handsome antique jewelry, suède pumps. She wore her

hair

tied neatly at the nape of her neck rather than long and loose, as she

used to,

but she still looked beautiful—she has a perfect oval face and robust

cheekbones. She put on a pair of jewel-rimmed reading glasses as she

brandished

another clipping, and said with satisfaction, “Ah, this is the

scandal!” The

conservative newspaper Libero had campaigned, unsuccessfully, for

Fallaci to be

made a Senator for Life, an honor conferred by the Italian President.

According

to the paper, the outgoing President, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, had

considered

giving Fallaci the title, but lost his nerve. “To me, in a sense, it

was a

relief,” Fallaci said. “I didn’t want to be Senator for Life, and stay

in Rome.

I would not know where to sit.” She hopped up to demonstrate, pointing

to the

left and the right sides of an imaginary aisle—she belonged to no

political

side. Nevertheless, with evident delight, she noted that Ciampi’s “wife

was

infuriated at him” for the decision. “For some time, she didn’t speak

to him.

Three days after Christmas, she managed to have me receive a bouquet of

white

flowers. That was cute.” I visited

Fallaci on the day before the Italian election, in which Prime Minister

Silvio

Berlusconi was defeated by the center-left candidate, Romano Prodi.

Fallaci

told me that she had not sent in an absentee ballot. She loved

referenda: “Do

you want the hunter to go hunting under your window? No! Do you want

the Koran

in your schools? No!” “No” was something Fallaci was happy to say. But

Berlusconi and Prodi were “two fucking idiots,” she said. “Why do the

people

humiliate themselves by voting? I didn’t vote. No! Because I have

dignity. . .

. If, at a certain moment, I had closed my nose and voted for one of

them, I

would spit on my own face.” Many of the

clippings on Fallaci’s table focussed on Adel Smith’s lawsuit against

her. She

said that she would not attend the trial, which is scheduled for later

this

month. Although she is no longer at risk of incarceration, she invoked

the

possibility. “Because, you know, I am a danger to myself if I get

angry,” she

said. “If they were thinking to give me three years in jail, I will say

or do

something for which they give me nine years! I am capable of everything

if I

get angry.” I’d always

thought of Fallaci as an icon of the nineteen-sixties—one of those

women who

had lived an emancipated life without ever calling herself a feminist,

an

insouciant heroine out of “The Golden Notebook” or “Bonjour Tristesse.”

She

denigrated marriage, got thrown out of nice restaurants for wearing

slacks, and

hung out with Anna Magnani and Ingrid Bergman. Her autobiographical

novel

“Letter to a Child Never Born” (1975) was a free woman’s despairing

confession

of ambivalence about bearing a child. “A Man” (1979) was a fictional

tribute to

her great love, the Greek resistance fighter Alexandros Panagoulis, who

died in

a suspicious automobile accident in Athens three years after they met.

Panagoulis had been imprisoned, and endured torture, for his failed

attempt on

the life of the Greek junta leader George Papadopoulos, in 1968. “I

didn’t want

to kill a man,” he told Fallaci in an interview. “I’m not capable of

killing a

man. I wanted to kill a tyrant.” As a political prisoner, Panagoulis

was

defiant toward his captors and wrote poetry in his own blood; Fallaci

considered him a model of what it is to be a man. I thought of her as a

product

of that heady time when big and bloody political matters were still at

stake in

Europe (dictators ruled Spain, Portugal, and Greece), but small,

sophisticated

cultural rebellions (movies, hair styles, poetic manifestos) made life

chic and

interesting. There’s some truth to this image, but Fallaci’s

sensibility is a

product less of the sixties than of the forties, and the struggle

against

Fascism in the Second World War. Fallaci was

born in Florence in 1929, to a family with a long history of rebellion.

Her

mother, Tosca, she said, was the orphaned daughter of an anarchist—“and

I tell

you those were people with balls! With balls! And they were the first

ones to

be executed.” On both sides of her family, she said, she had relatives

who

fought for the Risorgimento—“people who were always in jail.” Fallaci

was an

avid reader as a child (her parents lived modestly but splurged on

books), and

a favorite author was Jack London. His tales of brave acts in the face

of

savage nature inspired her to become a writer. She describes her

father,

Edoardo—a craftsman who became a leader in the anti-Fascist movement in

Tuscany, and who served time in prison for it—as a sweet man. “Heroes

can be

sweet,” she said, adding that Panagoulis had been that way, too. But

both of

Fallaci’s parents prized courage and toughness in their three

daughters. In

“The Rage and the Pride,” she tells a story about the Allied

bombardment of

Florence on September 25, 1943. She and her family took refuge in a

church as

the bombs began to fall. The walls were shaking—the priest cried out,

“Help us,

Jesus!”—and Oriana, who was the eldest, at fourteen, began to cry. “In

a

silent, composed way, mind you,” she writes. “No moans, no hiccups. But

Father

noticed it all the same, and, in order to help me, to calm me down,

poor

Father, he did the wrong thing. He gave me a powerful slap—he stared me

in the

eyes and said, ‘A girl does not, must not, cry.’ ” Fallaci says that

she’s

never cried since—not even when Panagoulis died. As a

teen-ager, Fallaci did clandestine work for the anti-Fascist

underground—she

had her own nom de guerre, Emilia, and she carried explosives and

delivered

messages. After Italy surrendered, in September, 1943, and American and

British

prisoners began escaping from prison camps, one of her tasks was to

accompany

them “past the lines” and to safe refuge. Fallaci was chosen because

she wore

her hair in pigtails and looked deceptively innocent. “It was so scary,

because

there were minefields, and you never knew where the mines were,” she

recalled.

“When my mother read that in a book later, she said, to my father, ‘You

would

have sacrificed newly born children! You and your ideas.’ And then she

said,

‘Well, but I had a feeling you were doing something like that.’ ” Fallaci’s

parents looked upon the Americans as their particular friends, and when

she was

in high school they insisted that she learn English when her classmates

were

studying French. It was the beginning of a lifelong affinity for

America, even

when, as during the Vietnam War, she was sharply critical of its

policies. “In

my old age, I have been thinking about this, and I have reached the

conclusion

that those who have physical courage also have moral courage,” she

said.

“Physical courage is a great test.” She added, “I know I have courage.

But I’m

not alone. My sister Neera was like me. And my second sister, Paola,

too. It

came from the education my parents gave us.” She proudly

told a story about her mother, which, like other recollections, sounded

as if

it might have been polished over time. “When my father was arrested, we

didn’t

know where they had him, so she went everywhere for two days and

finally she

found him, at the house of torture. It was called Villa Triste. They

killed

people there. And the Fascist major was named Mario Carità—Major

Charity.

Mother—I don’t know how she did it—she went to the office of Major

Charity,

passing a room that was full of blood on the floor, the blood of three

men who

had been arrested and tied together, and one of them was my father.

Carità

says, ‘Madam. I have no time to lose. Your husband will be executed

tomorrow

morning at six. You can dress in black.’ My mother got up—and I always

imagine

the scene this way, as if she were the Statue of Liberty—and my mother

said,

‘Mario Carità, tomorrow morning I shall dress in black, like you said.

But if

you are born from the womb of a woman, ask your mother to do the same,

because

your day will come very soon.’ You could think for a year before you

came up

with something like that—to her, it came.” Her mother was pregnant at

the time,

Fallaci went on. “She mounted on her bicycle, and all at once she had

pains so

terrible. She entered into a beautiful building and, in the atrium, she

lost

the child. She put it in, I don’t know, a handkerchief or something.

She

mounted the bicycle again. She rode home. I opened the door, and there

was

mother, as pale as snow. And before she entered she said, ‘Father will

be

executed tomorrow morning at six, and Elena’—that was the name she had

given

the baby—‘is dead.’ No tears.” In the end, Edoardo Fallaci was spared,

though

he spent additional time in jail. Fallaci’s sister Neera became a

writer, and

died of cancer; Paola is a perfectionist gardener—imagine a cross

between

Martha Stewart and Oriana—who raises prize-quality chickens on

Fallaci’s

property in rural Tuscany. Fallaci sees

the threat of Islamic fundamentalism as a revival of the Fascism that

she and

her sisters grew up fighting. She told me, “I am convinced that the

situation

is politically substantially the same as in 1938, with the pact in

Munich, when

England and France did not understand a thing. With the Muslims, we

have done

the same thing.” She elaborated, in an e-mail, “Look at the Muslims: in

Europe

they go on with their chadors and their burkas and their djellabahs.

They go on

with the habits preached by the Koran, they go on with mistreating

their wives

and daughters. They refuse our culture, in short, and try to impose

their

culture, or so-called culture, on us. . . . I reject them, and this is

not only

my duty toward my culture. Toward my values, my principles, my

civilization. It

is not only my duty toward my Christian roots. It is my duty toward

freedom and

toward the freedom fighter I am since I was a little girl fighting as a

partisan

against Nazi-Fascism. Islamism is the new Nazi-Fascism. With

Nazi-Fascism, no

compromise is possible. No hypocritical tolerance. And those who do not

understand this simple reality are feeding the suicide of the West.” Fallaci

refuses to recognize the limitations of this metaphor—say, the fact

that Muslim

immigration is not the same as an annexation by another state. And

although

European countries should indeed refuse to countenance certain cultural

practices—polygamy, “honor killings,” and anti-Semitic teachings, for

example—Fallaci tends to portray the worst practices of Islamic

fundamentalists

as representative of all Muslims. Certainly, European countries have

made some

foolish compromises in the name of placating Muslim residents. In

Germany, where

courts have ordered that Muslim religious instruction be offered in

schools,

just as Christian instruction is, critics have complained that the

Islamic

teaching often perpetuates a conservative version of Islam. The result,

the

historian Bernard Lewis argued, in a recent talk in Washington, is that

“Islam

as taught in Turkish schools is a sort of modernized, semi-secularized

version

of Islam, and Islam as taught in German schools is the full Wahhabi

blast.”

(This is a good reminder of why the American model of keeping religious

instruction out of public schools facilitates assimilation.) Many of

Fallaci’s

objections, however, have more to do with her aesthetic sensibilities.

For her,

hearing Muslim prayers in Tuscany—she does her own wailing imitation—is

a form

of oppression. Yet such examples do not rise to the level of argument

that she

wants to make, which is that the native culture of Italy will collapse

if

Muslims keep immigrating. “They live

at our expense, because they’ve got schools, hospitals, everything,”

she said

at one point, beginning to shout. “And they want to build damn mosques

everywhere.” She spoke of a new mosque and Islamic center planned for

Colle di

Val d’Elsa, near Siena. She vowed that it would not remain standing.

“If I’m

alive, I will go to my friends in Carrara—you know, where there is the

marble.

They are all anarchists. With them, I take the explosives. I make you

juuump in

the air. I blow it up! With the anarchists of Carrara. I do not want to

see

this mosque—it’s very near my house in Tuscany. I do not want to see a

twenty-four-metre minaret in the landscape of Giotto. When I cannot

even wear a

cross or carry a Bible in their country! So I BLOW IT UP! ” The

magnificently rebellious Oriana Fallaci now cultivates, it seems, the

prejudices of the petite bourgeoisie. She is opposed to abortion,

unless she

“were raped and made pregnant by a bin Laden or a Zarqawi.” She is

fiercely

opposed to gay marriage (“In the same way that the Muslims would like

us all to

become Muslims, they would like us all to become homosexuals”), and

suspicious

of immigration in general. The demonstrations by immigrants in the

United

States these past few months “disgust” her, especially when protesters

displayed the Mexican flag. “I don’t love the Mexicans,” Fallaci said,

invoking

her nasty treatment at the hands of Mexican police in 1968. “If you

hold a gun

and say, ‘Choose who is worse between the Muslims and the Mexicans,’ I

have a

moment of hesitation. Then I choose the Muslims, because they have

broken my

balls.” In “The Rage

and the Pride,” Fallaci portrays the attacks of September 11th as a

thunderclap

that woke her from a quiet, novel-writing existence and transformed

her, almost

unwillingly, into an anti-Islamic rebel. But Fallaci’s distaste for

Islam goes

way back. Reasonable worries about the rise of Muslim fundamentalism

were

combined with a visceral revulsion and the need for a new enemy, in the

post-Fascist, post-Communist world. Her interviews with Yasir Arafat

(whom she

loathed), Qaddafi (whom she also loathed), and even Muhammad Ali (whom

she

walked out on, she says, after he belched in her face) all fuelled her

antipathy toward the Muslim world. So did her experiences in Beirut

during its

disintegration, in the nineteen-eighties—the basis for her 1990 novel,

“Inshallah.” I started

wondering if Fallaci would tolerate any Muslim immigration, or any

mosque in

Europe, so I asked her these questions by e-mail, and she sent back

lengthy

replies. “The tolerance level was already surpassed fifteen or twenty

years

ago,” she wrote, “when the Left let the Muslims disembark on our coasts

by the

thousands. And it is well known . . . that I do not accept the

mendacity of the

so-called Moderate Islam. I do not believe that a Good Islam and a Bad

Islam exist.

Only Islam exists. And Islam is the Koran. And the Koran says what it

says.

Whatever its version. Of course there are exceptions. Also, considering

the

mathematical calculation of probabilities, some good Muslims must

exist. I mean

Muslims who appreciate freedom and democracy and secularism. But, as I

say in

the ‘Apocalypse,’ . . . good Muslims are few. So tragically few, in

fact, that

they must go around with bodyguards.” (Here she mentioned Ayaan Hirsi

Ali, the

Somali-born former member of the Dutch parliament, whom Holland,

shamefully,

declared last month that it would strip of her citizenship, citing an

irregularity in her 1997 asylum application.) She wrote that she found

my

question about whether she would tolerate any mosques in Europe

“insidious” and

“offensive,” because it “aims to portray me as the bloodthirsty

fanatics, who

during the French Revolution beheaded even the statues of the Holy

Virgin and

of Jesus Christ and the Saints. Or as the equally bloodthirsty fanatics

of the

Bolshevik Revolution, who burned the icons and executed the clergymen

and used

the churches as warehouses. Really, no honest person can suggest that

my ideas

belong to that kind of people. I am known for a life spent in the

struggle for

freedom, and freedom includes the freedom of religion. But the struggle

for

freedom does not include the submission to a religion which, like the

Muslim

religion, wants to annihilate other religions. Which wants to impose

its ‘Mein

Kampf,’ its Koran, on the whole planet. Which has done so for one

thousand and

four hundred years. That is, since its birth. Which, unlike any other

religion,

slaughters and decapitates or enslaves all those who live differently.” My second

meeting with Fallaci was a less inflammatory encounter. She is an

excellent

cook, and she made us lunch—cotechino sausage, polenta, mashed

potatoes, and

delicious little tarts with pine nuts and dried fruit—and served

champagne. I’d

never seen anyone approach certain kitchen tasks with such ferocity. “I

must

CRUSH the potatoes,” she declared. At one point, we spoke about

populist

leaders in Latin America, and the political left’s romance with them

over the

years; I mentioned Hugo Chávez, the President of Venezuela. “Mamma mia!

Mamma

mia! ” Fallaci shouted from the kitchen. “Listen,” she said more

calmly. “You

cannot govern, you cannot administrate, with an ignoramus.” When I

left, she

insisted on giving me a bag of chestnut flour and dictating a recipe

for a

dessert that she says children love. “If you make a mistake, you spoil

everything,”

she instructed, adding, “Get the good olive oil—not the kind they do in

New

Jersey.” Fallaci was

wearing a sweater and a skirt again that day. Late in life, she

realized that

skirts are more comfortable than the pants she had favored as a young

woman.

Besides, she wore pants when other women didn’t because she was “a

person who

had always gone against the current,” certainly since she started her

writing

career, at age sixteen, as a beat reporter for a Florentine newspaper.

Now that

everybody wore pants, what was the point? She had some evening dresses

upstairs, relics from a brief period in her early thirties when she’d

been a

little less serious. But now they felt to her “like monuments”; where

would she

wear them? We talked about the historical novel that she had set aside

after

September 11th, when “this Islam business kidnapped me,” her regrets

that she’s

never had children, and her long illness. One of her doctors, she said,

had

asked her recently, “Why are you still alive?” Fallaci responded,

“Dottore,

don’t do that to me. Someday I break your head.” She added, “Another

day, I

smiled and said, ‘You tell me—you are the doctor.’ See, I got offended.

‘I

don’t want to come here to hear about my death. Your duty is to speak

to me

about life, to keep me alive.’ ” She

surprised me with a charming story about being a young writer in New

York in

the nineteen-sixties. At the time, she recalled, she’d had a chance to

interview Greta Garbo—a mutual friend wanted to set it up. But Fallaci

admired

Garbo’s fierce and elegant privacy, and didn’t want to pursue the

matter. And

then one winter evening Fallaci was shopping at the Dover Delicatessen,

on

Fifty-seventh Street, and Garbo happened to be there: “You couldn’t not

recognize her. She was Greta Garbo. She was dressed like Greta

Garbo—with the

hair, the glasses. And she was choosing chicken with extreme care. She

would

look at a leg and toss it back, then the breast, and so on. And I felt

ashamed

of myself that I was observing her. I went in the other aisle, and I

remember I

got a lot of things, because I wanted her to go out and not go by me.”

It was a

rainy night and Fallaci had no umbrella. She recalled that Garbo, on

her way

out the door, stopped and held it open. “She said, ‘Here, Miss

Fallaci.’ I looked

like a poor, pitiful bird.” They walked together, under Garbo’s

umbrella, to

the corner of Third Avenue, and Fallaci—in a rare moment of

restraint—barely

said a word. After I had

interviewed Fallaci, I discovered two great examples of her journalism

that I

had not read before. In a witty 1963 article about Federico Fellini,

Fallaci

describes with wary, nervy thoroughness the many times and places that

the

great director kept her waiting. When she finally corners him, she

begins by

saying, “So then let us brace ourselves, Signor Fellini, and let us

discuss

Federico Fellini, just for a change. I know you find it hard: you are

so

withdrawing, so secretive, so modest. But it is our duty to discuss

him, for

the sake of the nation.” She goes on in this vein until Fellini cuts

her off,

saying, “Nasty liar. Rude little bitch.” In her introduction to the

interview,

she writes, “I used to be truly fond of Federico Fellini. Since our

tragic

encounter, I’m a lot less fond. To be exact, I’m no longer fond of him.

That

is, I don’t like him at all. Glory is a heavy burden, a murdering

poison, and

to bear it is an art. And to have that art is rare.” Equally absorbing,

in a

different way, was the section of her 1969 book, “Nothing, and So Be

It,” in

which she describes the events of October, 1968, in Mexico City, when

soldiers

shot and bayonetted hundreds of anti-government protesters. Fallaci was

detained with a group of students, and was ultimately shot three times.

“In

war, you’ve really got a chance sometimes, but here we had none,” she

writes.

“The wall they’d put us up against was a place of execution; if you

moved the

police would execute you, if you didn’t move the soldiers would kill

you, and

for many nights afterward I was to have this nightmare, the nightmare

of a

scorpion surrounded by fire, unable even to try to jump through the

fire

because if it did so it would be pierced through.” Dragged down the

stairs by

her hair and left for dead, Fallaci was ultimately taken to a hospital,

where

she underwent surgery to remove the bullets. One of the doctors who

cared for

her came close and murmured, “Write all you’ve seen. Write it!” She

did,

becoming a crucial witness to a massacre that the Mexican government

denied for

years. These pieces

showed Fallaci in her prime. In her e-mail, however, she told me that

she

didn’t really remember the interview with Fellini—only that she didn’t

like

him. And her memories of Mexico City in 1968 had largely devolved into

a

dislike of Mexicans. Fallaci’s virtues are the virtues that shine most

brightly

in stark circumstances: the ferocious courage, and the willingness to

say

anything, that can amount to a life force. But Fallaci never convinced

me that

Europe’s encounter with immigration is that sort of circumstance. Not that it

would matter to her. “You’ve got to get old, because you have nothing

to lose,”

she said over lunch that afternoon. “You have this respectability that

is given

to you, more or less. But you don’t give a damn. It is the ne plus

ultra of

freedom. And things that I didn’t used to say before—you know, there is

in each

of us a form of timidity, of cautiousness—now I open my big mouth. I

say, ‘What

are you going to do to me? You go fuck yourself—I say what I want.’ ” ♦ |