|

Tác giả/tác

phẩm ảnh hưởng nặng nề lên Pat [Patricia Highsmith] là Dos/Tội ác và Hình Phạt.

Như… Sến, em gặp ông già rậm râu là mê

liền, năm em 13 tuổi!

Trong nhật

ký, em coi Dos, là "Thầy", và coi Tội

Ác là 1 cuốn tiểu thuyết

suspense, trinh thám nghẹt thở.

Thomas Mann phán, Tội Ác là

một trong những cuốn

tiểu thuyết trinh thám lớn lao nhất của mọi thời.

Cuốn trứ

danh của Pat, Những kẻ lạ trên tàu, Strangers

on a Train, là từ Tội Ác

mà ra.

Em phán: "Tôi có ý nghĩ của riêng tôi về nghệ thuật, và nó như vầy:

điều mà hầu

hết mọi người coi là kỳ quặc, thiếu tính phổ cập, fantastic, lacking in

universality, thì tôi coi là cực yếu tính, the utmost essence, của sự

thực."

Tzvetan Todorov, khi viết về sự quái dị trong văn chương, đã cho thấy,

bằng cách

nào tiểu thuyết trinh thám hiện đại đã thay thế truyện ma quỉ của quá

khứ, và

những nhận định của ông áp dụng rất OK với tiểu thuyết của Pat: “căn

cước gẫy vụn,

bể nát, những biên giới giữa cá nhân và môi trường chung quanh bị phá

vỡ, sự mù

mờ, lấp lửng giữa thực tại bên ngoài và ý thức bên trong”, đó là những

yếu tố

thiết yếu làm nền cho những đề tài quái dị.

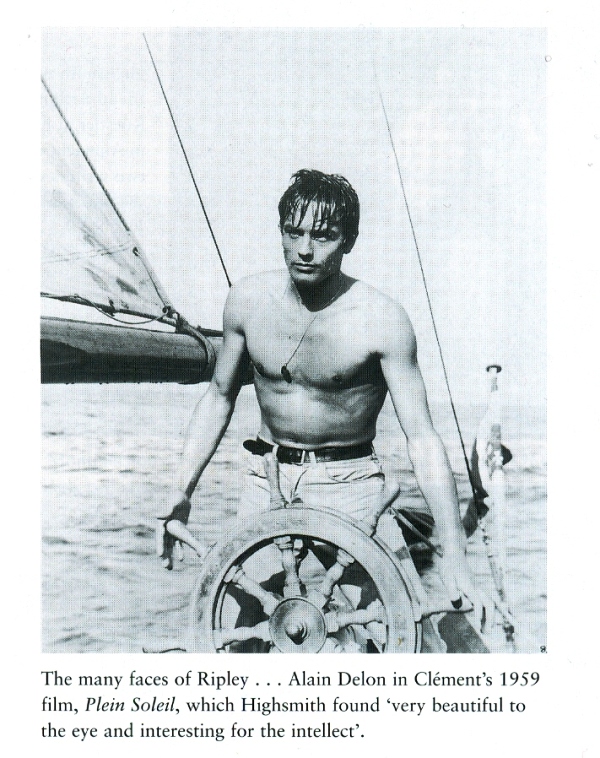

GCC biết đến

Patricia Highsmith qua phim Plein Soleil, Alain Delon

đóng vai Mr. Ripley. Thời còn Sài Gòn. Còn đi học, hoặc mới

đi làm.

Sau đó, mò coi truyện.

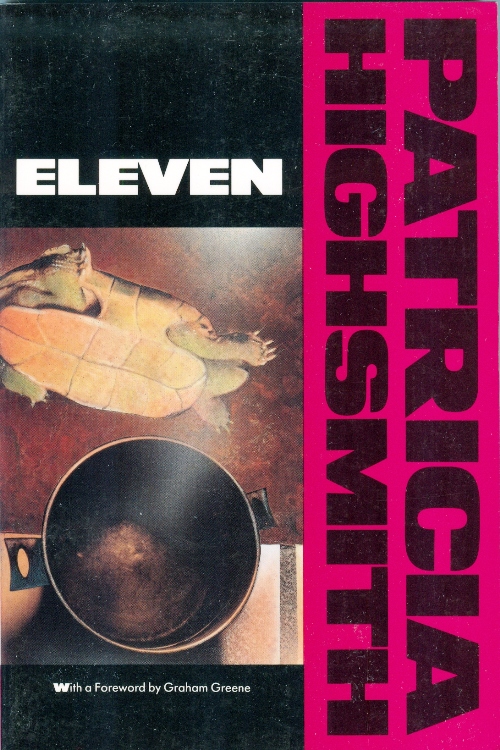

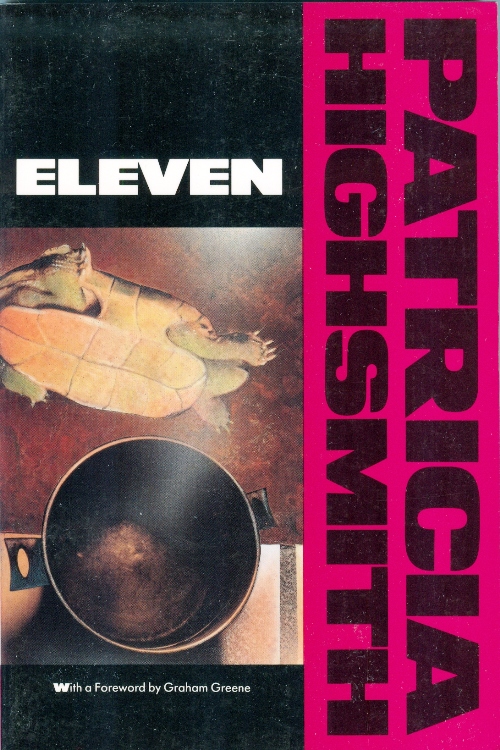

Mua Eleven, do đọc bài giới thiệu của Grahm Greene.

Truyện trinh

thám của PH, theo GCC "khủng" hơn hết, so với các tác giả khác, đúng

như Greene viết, bà tạo ra 1 thế giới của riêng bà, mỗi lần chúng ta mò

vô, là

một lần thấy ơn ớn.

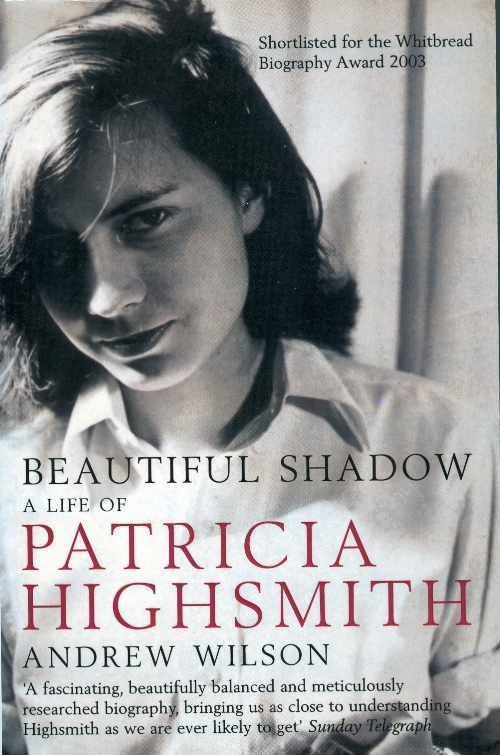

Trong cuốn tiểu sử của bà, Cái bóng

xinh đẹp, Beautiful shadow, người viết

trích dẫn 1 câu trong nhật ký của bà, và là 1 câu trích dẫn

Kierkegaard:

Mỗi cá

nhân con người thì có nhiều cái bóng tạo thành những nếp gấp, tất cả

những cái

bóng đó thì giống người đó, và thi thoảng, có 1 cái bèn chiếm luôn chỗ

của người

đó.

Nguyên văn câu tiếng Anh, khác 1 tí, so với câu của GCC:

"The

individual has manifold shadows, all of which resemble him, and from

time to

time have equal claim to be the man himself."

Kierkegaard,

quoted in Highsmith’s 1949 journal

Miss

Highsmith is a crime novelist whose books one can reread many times.

There are

very few of whom one can say that. She is a writer who has created a

world of

her own - a world claustrophobic and irrational which we enter each

time with a

sense of personal danger, with the head half turned over the shoulder,

even

with a certain reluctance, for these are cruel pleasures we are going

to

experience, until somewhere about the third chapter the frontier is

closed

behind us, we cannot retreat, we are doomed to live till the story's

end with

another of her long series of wanted men.

GG

Foreword

by

Grallam

Greene

Miss

Highsmith is a crime novelist whose books one can reread many times.

There are

very few of whom one can say that. She is a writer who has created a

world of

her own - a world claustrophobic and irrational which we enter each

time with a

sense of personal danger, with the head half turned over the shoulder,

even

with a certain reluctance, for these are cruel pleasures we are going

to

experience, until somewhere about the third chapter the frontier is

closed

behind us, we cannot retreat, we are doomed to live till the story's

end with

another of her long series of wanted men.

It makes the

tension worse that we are never sure whether even the worst of them,

like the

talented Mr Ripley, won't get away with it or that the relatively

innocent

won't suffer like the blunderer Walter on the relatively guilty escape

altogether like Sydney Bartleby in A. Suspension of Mercy. This is a

world without

moral endings. It has nothing in common with the heroic world of her

peers,

Hammett and Chandler, and her detectives (sometimes monsters of cruelty

like

the American Lieutenant Corby of The Blunderer or dull sympathetic

rational characters

like the British Inspector Brockway) have nothing in common with the

romantic

and disillusioned private eyes who will always, we know, triumph

finally over

evil and see that justice is done, even though they may have to send a

mistress

to the chair.

Nothing is

certain when we have crossed this frontier.

It is not the world as we once believed we knew it, but it is

frighteningly

more real to us than the house next door. Actions arc sudden and

impromptu and

the motives sometimes so inexplicable that we simply have to accept

them on

trust. I believe because it is impossible. Her characters are

irrational, and

they leap to life in their very lack of reason; suddenly we realize how

unbelievably

rational most fictional characters are as they lead their lives from A

to Z,

like commuters always taking the same train. The

motives of these characters are never inexplicable because they are so

drearily

obvious. The characters are as Hat as a mathematical symbol. We

accepted them

as real once, but when we look back at them from Miss Highsmith's side

of the frontier,

we realize that our world was not really as rational as all that.

Suddenly with

a sense of fear we think, 'Perhaps I really belong here,' and going out

into

the familiar street we pass with a

shiver of apprehension the offices of the American Express, the centre,

for so

many of Miss Highsmith's dubious men, of their rootless European

experience,

where letters are to be picked up (though the name on the envelope is

probably false)

and travellers' cheques are to be cashed (with a forged signature) .

Miss

Highsmith's short stories do not let us down, though we may be able

sometimes

to brush them off more easily because of their brevity. We haven't

lived with

them long enough to be totally absorbed. Miss Highsmith is the poet of

apprehension

rather than fear. Fear after a time, as we all learned in the blitz, is

narcotic, it can lull one by fatigue into sleep, but apprehension nags

at the

nerves gently and inescapably. We have to learn to live with it. Miss

Highsmith's finest novel to my mind is The Tremor of Forgery, and if I

were to be

asked what it is about I would reply, 'Apprehension'.

In her short

stories Miss

Highsmith has naturally to adopt a different method. She is after the

quick

kill rather than the slow encirclement of the reader, and how admirably

and

with what field-craft she hunts us down. Some of these stories were

written

twenty years ago, before her first novel, Strangers

on a Train, but we have no sense

that she is

learning her craft by false starts, by trial and error. 'The Heroine',

published nearly a quarter of a century ago, is as much a study of

apprehension

as her last novel. We can feel how dangerous (and irrational) the young

nurse

is from her first interview. We want to cry to the parents, 'Get rid of

her

before it's too late'.

My own

favourite in this collection is the story 'When the Fleet Was In at

Mobile'

with the moving horror of its close here is Miss Highsmith at her

claustrophobic best. 'The Terrapin', a late Highsmith, is a cruel story

of

childhood which can bear comparison with Saki's masterpiece, 'Sredni

Vashtar',

and for pure physical horror, which is an emotion rarely evoked by Miss

Highsmith, 'The Snail-Watcher' would be hard to beat.

Mr Knoppert has

the same attitude to his snails as Miss Highsmith to human beings. He

watches

them with the same emotionless curiosity as Miss Highsmith watches the

talented

Mr Ripley:

Mr Knoppert

had wandered into the kitchen one evening for a bite of something

before

dinner, and had happened to notice that a couple of snails in the china

bowl on

the draining board were behaving very oddly. Standing more or less on

their

tails, they were weaving before each other for all the world like a

pair of

snakes hypnotized by a flute player. A moment later, their faces came

together

in a kiss of voluptuous intensity. Mr Knoppert bent closer and studied

them from all angles. Something else was happening: a protuberance like

an ear

was appearing on the right side of the head of both snails. His

instinct told

him that he was watching a sexual activity of some sort.

Graham Greene

|