|

Cô bạn, cô phù dâu ngày nào, Gấu gặp

lại ở hải ngoại. Cô phán, cực kỳ bi thương, cực kỳ hạnh phúc,

tại làm sao mà bao nhiêu năm trời, tình cảm của

anh dành cho tôi vẫn như ngày nào.

Nhờ gặp lại cô, Gấu viết lại được, không chỉ thế, mà còn làm được tí thơ!

Bài viết về cô, Cầm Dương Xanh, được một vị nữ độc giả, Bắc

Kít, Hà Lội, mê quá, bệ ngay về trang FB của cô.

Cô tình cờ thấy trang TV, trong khi lướt net, tìm tài liệu về Camus.

Có lẽ đã đến lúc cần nghiêm túc nghĩ đến

việc mở

một chuyên đề đích thực về Cioran :p

Blog NL

Bài viết về Ciroran của Charles Simic thật tuyệt. Gấu cứ tính đi hoài, mà cứ lu bu hoài.

Mới lật ra đi 1 đường loáng thoáng, vớ được câu này thật tuyệt:

Con người, bị đá văng ra khỏi Thiên Đàng, với 1 tí

tưởng tượng, đủ cho nó cảm thấy đời mình sao rất đỗi bi thương!

Ui chao, hồi còn trẻ, bị em bỏ, bị cuộc chiến hành, không

làm sao dám bỏ chạy, đúng là tâm trạng

Gấu khi đó.

Những ngày Mậu Thân căng thẳng,

Đại Học

đóng cửa, cô bạn về quê, nỗi nhớ bám riết vào da thịt thay cho cơn bàng

hoàng

khi cận kề cái chết theo từng cơn hấp hối của thành phố cùng với tiếng

hỏa tiễn

réo ngang đầu. Trong những giờ phút lặng câm nhìn bóng mình run rẩy

cùng với

những thảm bom B52 rải chung quanh thành phố, trong lúc cảm thấy còn

sống sót,

vẫn thường tự hỏi, phải yêu thương cô bạn một cách bình thường, giản dị

như thế

nào cho cân xứng với cuộc sống thảm thương như vậy...

Bạn đọc TV để ý, không có chấm câu. Câu văn dài thòng, như bè rau ruống!

Cô bạn, cô phù dâu ngày nào, Gấu gặp

lại ở hải ngoại. Cô phán, cực kỳ bi thương, cực kỳ hạnh phúc,

tại làm sao mà bao nhiêu năm trời, tình cảm của

anh dành cho tôi vẫn như ngày nào.

Nhờ gặp lại cô, Gấu viết lại được, không chỉ thế, mà còn làm được tí thơ!

Bài viết về cô, Cầm Dương Xanh, được một vị nữ độc giả, Bắc

Kít, Hà Lội, mê quá, bệ ngay về trang FB của cô.

Cô tình cờ thấy trang TV, trong khi lướt net, tìm tài liệu về Camus.

Cầm

Dương Xanh

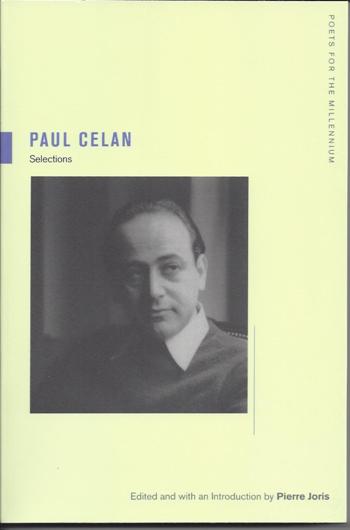

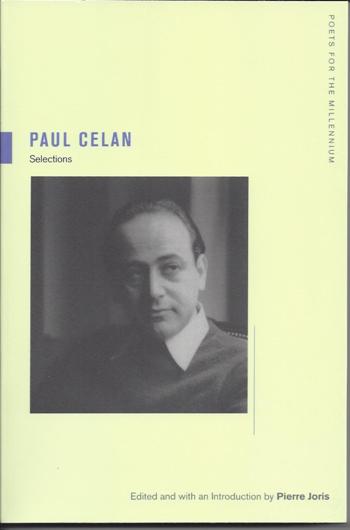

ENCOUNTERS

WITH PAUL CELAN

E. M. CIORAN

Précis de decomposition, my first book written in

French,

was published in I949 by Gallimard. Five works of mine had been

published in

Romanian. In 1937, I arrived in Paris on a scholarship from the

Bucharest

Institut francais, and I have never left. It was only in I947, though,

that I

thought of giving up my native language. It was a sudden decision.

Switching

languages at the age of thirty-seven is not an easy undertaking. In

truth, it

is a martyrdom, but a fruitful martyrdom, an adventure that lends

meaning to

being (for which it has great need!). I recommend to anyone going

through a

major depression to take on the conquest of a foreign idiom, to

reenergize

himself, altogether to renew himself, through the Word. Without my

drive to conquer

French, I might have committed suicide. A language is a continent, a

universe,

and the one who makes it his is a conquistador. But let us get to the

subject.

...

The German

translation of the Précis proved

difficult. Rowohlt, the publisher, had engaged an unqualified woman,

with

disastrous resuits. Someone else had to be found. A Romanian writer,

Virgil Ierunca,

who, after the war, had edited a literary journal in Romania, in which

Celan's

first poems were published, warmly recommended him. Celan, whom I knew

only by

name, lived in the Latin quarter, as did 1. Accepting my offer, Celan

set to

work and managed it with stunning speed. I saw him often, and it was

his wish

that I read closely along, chapter by chapter, as he progressed,

offering

possible suggestions. The vertiginous problems involved in translation

were at that

time foreign to me, and I was far from assessing the breadth of it.

Even the

idea that one might have a committed interest in it seemed rather

extravagant

to me. I was to experience a complete reversal, and, years later, would

come to

regard translation as an exceptional undertaking, as an accomplishment

almost

equal to that of the work of creation. I am sure, now, that the only

one to

understand a book thoroughly is someone who has gone to the trouble of

translating it. As a general rule, a good translator sees more clearly

than the

author, who, to the extent that he is in the grips of his work, cannot

know its

secrets, thus its weaknesses and its limits. Perhaps Celan, for whom

words were

life and death, would have shared this position on the art of

translation.

In 1978,

when Klett was reprinting Lehre vom Zerfall

(the German Précis), I was asked to correct any errors

that might exist. I was

unable to do it myself, and refused to engage anyone else. One does not

correct Celan. A few months before he

died, he said to me that he would like to review the complete text.

Undoubtedly, he would have made numerous revisions, since, we must

remember,

the translation of the Précis dates

back to the beginning of his career as a translator. It is really a

wonder that

a noninitiate in philosophy dealt so extraordinarily well with the

problems

inherent in an excessive, even provocative, use of paradox that

characterizes

my book.

Relations

with this deeply torn being were not simple. He clung to his biases

against one

person or another, he sustained his mistrust, all the more so because

of his

pathological fear of being hurt, and everything hurt him. The slightest

indelicacy, even unintentional, affected him irrevocably. Watchful,

defensive

against what might happen, he expected the same attention from others,

and

abhorred the easygoing attitude so prevalent among the Parisians,

writers or

not. One day, I ran into him in the street. He was in a rage, in a

state

nearing despair, because X, whom he had invited to have dinner with

him, had

not bothered to come. Take it easy, I said to him, X is like that, he

is known

for his don't-give-a-damn attitude. The only mistake was expecting him.

Celan,

at that time, was living very simply and having no luck at all finding

a decent

job. You can hardly picture him in an office. Because of his morbidly

sensitive

nature, he nearly lost his one opportunity.

The very day

that I was going to his home to lunch with him, I found out that there

was a

position open for a German instructor at the Ecole normale supérieure,

and that

the appointment of a teacher would be imminent. I tried to persuade

Celan that

it was of the utmost importance for him to appeal vigorously to the

German

specialist in whose hands the matter resided. He answered that he would

not do

anything about it, that the professor in question gave him the cold

shoulder,

and that he would for no price leave himself open to rejection, which,

according to him, was certain. Insistence seemed useless.

Returning

home, it occurred to me to send him by pneumatique,

a message in which I pointed out to him the folly of allowing such an

opportunity

to slip away. Finally he called the professor, and the matter was

settled in a

few minutes. "I was wrong about him," he told me later. I won't go so

far as to propose that he saw a potential enemy in every man; however,

what was

certain was that he lived in fear of disappointment or outright

betrayal. His

inability to be detached or cynical made his life a nightmare. I will

never

forget the evening I spent with him when the widow of a poet had, out

of

literary jealousy, launched an unspeakably vile campaign against him in

France

and Germany, accusing him of having plagiarized her husband. "There

isn't

anyone in the world more miserable than I am," Celan kept saying. Pride

doesn't soothe fury, even less despair.

Something

within him must have been broken very early on, even before the

misfortunes

which crashed down upon his people and himself. I recall a summer

afternoon

spent at his wife's lovely country place, about forty miles from Paris.

It was

a magnificent day.

Everything

invoked relaxation, bliss, illusion. Celan, in a lounge chair, tried

unsuccessfully to be lighthearted. He seemed awkward, as if he didn't

belong,

as though that brilliance was not for him. What can I be looking for

here? he

must have been thinking. And, in fact, what was he seeking in the

innocence of

that garden, this man who was guilty of being unhappy, and condemned

not to

find his place anywhere? It would be wrong to say that I felt truly ill

at

ease; nevertheless, the fact was that everything about my host,

including his

smile, was tinged with a pained charm, and something like a sense of

nonfuture.

Is it a

privilege or a curse to be marked by misfortune? Both at once. This

double face

defines tragedy. So Celan was a figure, a tragic being. And for that he

is for

us somewhat more than a poet .

E. M. Cioran, "Encounters

with

Paul Celan," in Translating Tradition: Paul Celan in France, edited by

Benjamin Hollander (San Francisco: ACTS 8/9,1988): 151-52.

Is it a

privilege or a curse to be marked by misfortune? Both at once. This

double face

defines tragedy. So Celan was a figure, a tragic being. And for that he

is for

us somewhat more than a poet .

Đặc quyền,

hay trù ẻo, khi nhận "ân sủng" của sự bất hạnh?

Liền tù tì cả

hai!

Cái bộ mặt

kép đó định nghĩa thế nào là bi kịch.

Và như thế, Celan là 1 hình tượng, một

con người bi thương.

Và như thế, ông bảnh hơn nhiều, chứ không "chỉ là 1 nhà

thơ"!

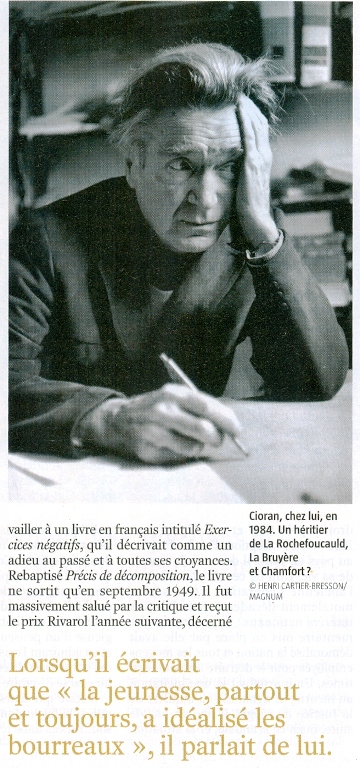

Triết Gia Của Sự Mất Ngủ

Trên tờ Books, có bài về

Philo, thú: Bằng cách nào Emil trở thành Cioran.

Khi ông ta viết, "tuổi

trẻ, ở đâu cũng thế, và luôn luôn là như vậy, thần tượng hóa, lý tưởng

hoá,

những tên đao phủ thủ”, ông nói về ông.

Cioran, là Thầy của CVD. GCC đoán thế, hình như anh có thừa nhận điều

này?

Và sau này, nếu CVD…sống sót, như… Murakami, thì có lẽ sẽ có 1 bài

viết, “Bằng

cách nào đao phủ thủ trở thành... dê tế thần”!

Hà, hà!

CVD lúc mới xuất hiện, cũng

trảm nhiều tác giả lắm, [trong số đó, có HH!]

Cioran là Thầy của NTV, cái này thì chắc chắn. Anh cũng chẳng thèm

chối, và còn

rất ư tự hào!

Nhưng theo GCC, NTV thua

thầy xa.

Thầy chán đời, mà để lại hằng hà tác phẩm.

Còn NTV, một con số không to tổ bố.

Nhớ, có lần ngồi đấu bia,

và tán láo, nghe GCC nhắc tới kỷ niệm về ông anh nhà thơ, và lời khuyên

của

ông, phải dịch, dịch, dịch, dịch tưới, đừng sợ sai, sai tới đâu sửa tới

đó,

không là không thể nào có tác phẩm… Anh buồn rầu than, giá mà hồi trẻ,

tao gặp

TTT, thì cũng đã có vô số tác phẩm rồi. Hồi đó, ngu quá, cứ sợ dịch sai!

Nhưng NTV cũng có chút an ủi. Khi anh dịch Cao Hành Kiện, TTT đọc, thú

quá,

phôn, khen, đúng giọng văn của tác giả Thằng Kình, tức Nguyễn

Đức Quỳnh.

NDQ cũng là Thầy của NTV. Anh có nhiều kỷ niệm về NDQ, giá mà viết ra

thì cũng

thú lắm. Thí dụ cái câu phán nổi tiếng của NDQ là GCC nghe qua NTV:

Quốc Gia thì như bát cơm hẩm, trộn cứt, VC thì như bát cơm gạo tám

thơm, trộn

thuốc độc.

Tuyệt cú!

Tuổi trẻ, ở đâu cũng thế,

và luôn luôn là như vậy, thần tượng hóa, lý tưởng hoá, những tên đao

phủ thủ.

Thảo nào tuổi trẻ Mít mê như điên Hoàng Phủ Ngọc Tường, chọn quốc ca là

thơ của

“hit man” VC.

Không biết

CVD ngoài đời có đẹp giai như sư phụ? Tính về thăm hoài, và, nếu có

thể, xin...

phò, nhưng sợ VC đá đít như Thầy Kuốc.

Thăm “Sách

Huyền” nữa chứ.

Nhớ Hà Nội

quá!

Hà, hà!

Không biết

CVD ngoài đời có đẹp giai như sư phụ? Tính về thăm hoài, và, nếu có

thể, xin...

phò, nhưng sợ VC đá đít như Thầy Kuốc.

Thăm “Sách

Huyền” nữa chứ.

Nhớ Hà Nội

quá!

Hà, hà!

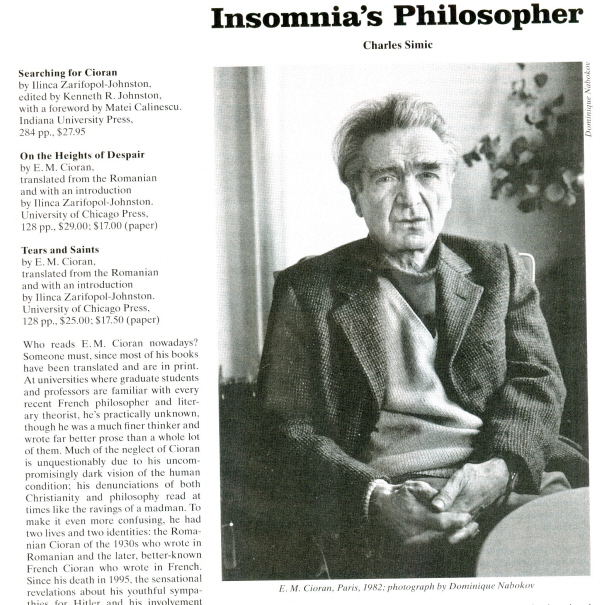

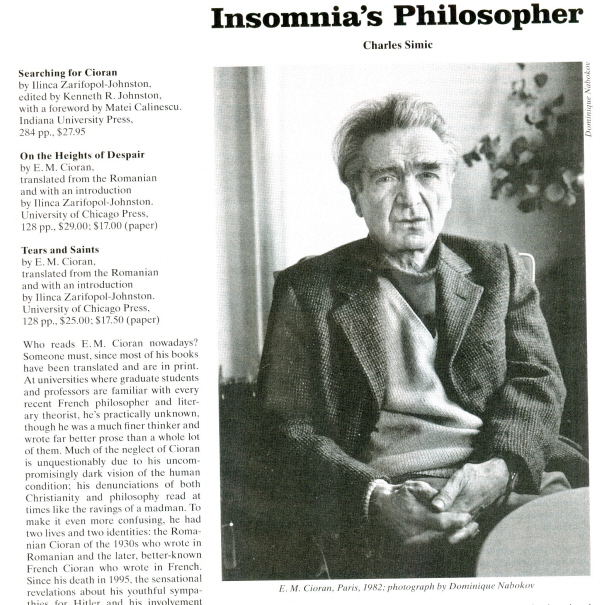

Who reads

E.M. Cioran nowadays? Someone must, since most of his books have been

translated and are in print. At universities where graduate students

and

professors are familiar with every recent French philosopher and

literary

theorist, he’s practically unknown, though he was a much finer thinker

and

wrote far better prose than a whole lot of them. Much of the neglect of

Cioran

is unquestionably due to his uncompromisingly dark vision of the human

condition;

his denunciations of both Christianity and philosophy read at times

like the

ravings of a madman. To make it even more confusing, he had two lives

and two

identities: the Romanian Cioran of the 1930s who wrote in Romanian and

the

later, better-known French Cioran who wrote in French. Since his death

in 1995,

the sensational revelations about his youthful sympathies for Hitler

and his

involvement with the Iron Guard, the Romanian pro-fascist, nationalist,

and

anti-Semitic movement in the 1930s, have also contributed to his

marginalization. And yet following the publication in 1949 of the first

book he

wrote in French, he was hailed in France as a stylist and thinker

worthy of

comparison to great seventeenth- and eighteenth-century moralists like

La

Rochefoucauld, La Bruyère, Chamfort, and Vauvenargues.

This is what

makes Searching for Cioran by

the late Ilinca Zarifopol-Johnston, who didn’t

live to finish her book, so valuable. It tells the story of his

Romanian years

and gives a fine account of the personal and political circumstances in

which

both his philosophical ideas and his brand of nationalism were formed.

In later

years, Cioran spoke rarely of that shameful period in his life and

never—except

to allude vaguely to his “youthful follies”—talked openly of his one

political

tract, Romania’s Transfiguration (1936), a short, demented book in

which he

prescribed how his native country could overcome its second-rate

historical

status through radical, totalitarian methods. Along with Mircea Eliade,

the

philosopher and historian of religion, the playwright Eugène Ionesco,

and many

others, equally eminent but less known abroad, he was a member of

Romania’s

“Young Generation,” the “angry young men” responsible for both a

cultural

renaissance and apocalyptic nationalism in the 1930s. To understand

what led

Cioran to leave Romania and become disillusioned with ideas he espoused

in his

youth, it’s best to start at the beginning.

Emil Cioran

was born in 1911, the second of three children, in the remote mountain

village

of Ra˘s¸inari near the city of Sibiu in southern Transylvania, which at

that

time was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father,

Emilian, was a

Romanian Orthodox priest who came from a long line of priests, as did

his

mother, Elvira. He loved his native landscape with its streams, hills,

and

woods where he ran free with other kids, even telling one interviewer,

“I don’t

know of anyone with a happier childhood than mine.”

At other

times, when not moved by nostalgia, he called …

|