|

He Told the Truth About China’s Tyranny Another essay deals with the "Land

Problem." In the Mao era, farmers lost their land and were reduced to

virtual serfdom in the "communes." They were bound to work on land that

was no longer theirs. During the catastrophic madness of the Great Leap

Forward the poverty of the farmers reached the point where they did not

have food to eat or clothes to wear. In some places people were driven

to cannibalism. More than forty million people starved to death during

the great Mao-made famine of 1958-1962. Not long after Mao died in

1976, a "half-baked liberation" of the serfs took place: farmers were

given the right not to own land but to use it, unless farmland needed

to be "developed" and it then reverted to state property.

Officials wielding the power of the state and invoking "government ownership of land" have colluded with businessmen all across our country .... The biggest beneficiaries of the resultant land deals, at all levels, have been the Communist regime and the power elite .... Farmers are the weakest among the weak. Without a free press and an independent judiciary, they have no public voice, no right to organize farmers' associations, and no means of legal redress .... And that is why, when all recourse within the system ... is stifled, people are naturally drawn to collective action outside the system .... Một tiểu luận

khác trong "Không Kẻ Thù, Không Hận Thù" viết về “Vấn Lạn Đất”. Dưới

thời

Mao, chủ

đất mất đất của mình và biến thành tên nông nô, [bị kết án bởi

cái gọi là

chuyên chính vô sản], của những “hợp tác xã", buộc phải cày như trâu,

trên

cũng mảnh

đất của chính mình, nhưng đếch còn là của mình. Trong thời kỳ khùng

điên

Bước Nhảy

Vọt Vĩ Đại, nỗi đói khổ của người nông dân đạt tới "đỉnh của đỉnh": họ

đếch còn cái

gì để ăn, hay quần áo để mặc. Ở một vài nơi, dân chúng bị đẩy đến tình

trạng ăn

thịt lẫn nhau. Hơn bốn chục triệu con nguời chết đói trong trận đói vĩ

đại do

Mao làm ra, thời kỳ 1958-1962. Chẳng lâu sau khi Mao ngỏm, vào năm

1976,

một cú

"giải phóng nướng 1 nửa" [tạm dịch cái từ khó dịch “half-baked

liberarion”] đã xẩy ra: nông dân được quyền, không phải sở hữu đất,

nhưng mà

là sử dụng nó, trừ khi nào đất khu vực được trưng thu, dành vào việc

“phát triển”, nó trở thành tài sản của nhà nước. Hình như hơi bị giống trường hợp đồng chí “Vươn” của Tiên Lãng: Đảng giao đất cho chú Vươn để sử dụng, không phải để sở hữu, và khi Đảng cần đất để phát triển, Đảng lấy lại, dù chú Vươn tự mình phát triển mảnh đất, biến nó to bằng năm bằng mười so với lúc trước, bằng cách lấn biển? Viên

chức

dùng uy quyền

của

nhà nước,

nhắc

nhở

quyền

chủ

đất

của

nhà nước,

cấu

kết

với

đám con buôn, trên địa

bàn cả

nước…

Những

người

thụ

hưởng

mập,

bẫm,

từ

những

cú làm ăn này, thì là chế

độ

CS, và đám ngồi

trên đầu

nhân dân, tức

đám tinh anh nắm

quyền

lực…

Nông dân là những

người

yếu

nhất

trong số

những

kẻ

yếu.

Không có một

nền

báo chí tự

do, và 1 nền

luật

pháp độc

lập,

họ

không có tiếng

nói công cộng,

không có quyền

thành

lập

những

hiệp

hội

của

nông dân, và vô phương

đòi hỏi

bồi

thường

thiệt

hại…

Bởi

thế,

một

khi mọi

chạy

chọt

bên trong chế

độ,

hệ

thống…

bị

hỏng

cẳng,

người

dân đành trông vào thứ

võ khí tự

chế,

và hành động

tập

thể

ở

bên ngoài hệ

thống.

Another essay deals with the "Land

Problem." In the Mao era, farmers lost their land and were reduced to

virtual serfdom in the "communes." They were bound to work on land that

was no longer theirs. During the catastrophic madness of the Great Leap

Forward the poverty of the farmers reached the point where they did not

have food to eat or clothes to wear. In some places people were driven

to cannibalism. More than forty million people starved to death during

the great Mao-made famine of 1958-1962. Not long after Mao died in

1976, a "half-baked liberation" of the serfs took place: farmers were

given the right not to own land but to use it, unless farmland needed

to be "developed" and it then reverted to state property. Officials

wielding the power of the state and invoking "government ownership of

land" have colluded with businessmen all across our country .... The

biggest beneficiaries of the resultant land deals, at all levels, have

been the Communist regime and the power elite .... Farmers are the

weakest among the weak. Without a free press and an independent

judiciary, they have no public voice, no right to organize farmers'

associations, and no means of legal redress .... And that is why, when

all recourse within the system ... is stifled, people are naturally

drawn to collective action outside the system ....  NYRB

Feb 9, 2012 Bài viết này

bảnh lắm. Simon Leys là 1 chuyên gia về xứ Tầu. “Trí thức là

người lao động trí óc... giá trị của trí thức là giá trị sản phẩm anh

ta làm ra

chẳng liên quan gì đến vai trò phản biện xã hội.” “Tôi là người

thuộc thế hệ đã nghe Stalin phán, ‘Nhà văn là những kỹ sư của tâm hồn

nhân

loại’, và điều này đã đem đến cho một vài người một số tác phẩm tệ vô

cùng chưa

từng được viết ra” He Told the Truth About

China’s

Tyranny Simon Leys No Enemies,

No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems by Liu

Xiaobo, edited by

Perry Link, Tienchi

Martin-Liao, and Liu Xia, and with a foreword by Vaclav Havel. Belknap

Press/Harvard University Press, 366 pp., $29.95 Better than

the assent of the crowd: The dissent

of one brave man! -Sima Qian

(145-90 BC) Records of the Grand

Historian Truth will

set you free. -Gospel

according to John The economic

rise of China now dominates the entire landscape of international

affairs. In

the eyes of political analysts and statesmen, China is seen as

potentially

"the world's largest economic power by 2019." Experts from financial

institutions suggest an even earlier date for such a prognosis:

"China," one has said, "will become the largest economy in the

world by 2016." This fast transformation is rightly called "the

Chinese miracle." The general consensus, in China as well as abroad, is

that

the twenty-first century will be "China's century." International

statesmen fly to Peking, while businessmen from all parts of the

developed

world are rushing to Shanghai and other provincial metropolises in the

hope of

securing deals. Europe is begging China to come to the rescue of its

ailing

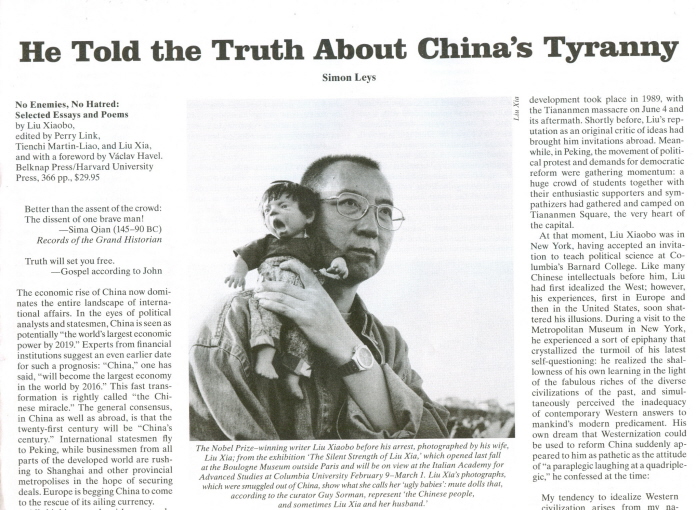

currency. Born in 1955

in northeastern China, Liu truly belongs to the generation of "Mao's

children," which, by an interesting paradox, eventually produced the

boldest dissenters and most articulate activists in favor of

democracy-for

example, Wei Jingsheng, hero of the Democracy Wall episode in Peking

between

1978 and 1979, who spent eighteen harsh years in prison before being

exiled to

the West. Liu Xiaobo pays frequent homage to these early pioneers. He

was too

young to participate in the Cultural Revolution, but this

movement-ironically-had a positive impact upon his life. My

tendency to idealize Western civilization

arises from my nationalistic desire to use the West in order to reform

China.

But this has led me to overlook the flaws of Western culture .... I

have been

obsequious toward Western civilization, exaggerating its merits, and at

the

same time exaggerating my own merits. I have viewed the West as if it

were not

only the salvation of China but also the natural and ultimate

destination of

all humanity. Moreover I have used this delusional idealism to assign

myself

the role of savior ....

While Liu

was still in New York, the student movement in Peking continued to

develop, not

realizing that it was now set on a collision course with the hard-line

faction

of the Communist leadership-the faction to which Deng Xiaoping was

finally to

give free rein. But Liu sensed that a crisis would soon be reached, and

he made

a grave and generous decision: he gave up the safety and comfort of his

New

York academic appointment and rushed back to Peking. He did not leave

the

square during the last dramatic days of the students' demonstration; he

desperately tried to persuade them that democratic politics must be

"politics without hatred and without enemies," and simultaneously,

after martial law was imposed, he negotiated with the army in the hope

of

obtaining a peaceful evacuation of the square. Thanks to

his intervention, countless lives were saved, though in the end he

could not

prevent wider carnage-we still don't know how many students, innocent

bystanders, and even volunteer rescuers disappeared during the

bloodbath of

that final night. Liu himself was arrested in the street three days

after the

massacre and imprisoned without trial for the next two years. He came

out of

jail a changed man. He was dismissed from the university and banned

from

publishing and from giving any public lectures within China. "Dictatorship

of the proletariat" has

become a rigid, purely formal structure, protecting the tyranny of a

minority-or of a single person; the way of the future, towards true

modernization, is parliamentary democracy-on the Western model. This

transformation would probably require a fairly long period of

transition; yet

it is feasible, as it is already shown by the examples of Taiwan and

South

Korea .... All the

essays of Liu Xiaobo included in the present volume deal with a period

of

twenty years-from Tiananmen to Charter 08. During this period, though

several

times arrested and detained without trial, Liu was active in freelance

political journalism. Having no regular employment, he managed to make

a precarious

living with his pen. As for the

judicial system-also used by the Party to protect its monopoly of

power-it is

utterly reluctant to tackle issues involving the alliance between the

Party and

the underworld: In

China the underworld and officialdom have

interpenetrated and become one. Criminal elements have become

officialized as officials

have become criminalized. Underworld chiefs carry tittles in the

National

People's Congress and the People's Political Consultative Conference,

while

civil officials rely on the underworld to keep the lid on local

society. Another

essay deals with the "Land Problem." In the Mao era, farmers lost

their land and were reduced to virtual serfdom in the "communes."

They were bound to work on land that was no longer theirs. During the

catastrophic madness of the Great Leap Forward the poverty of the

farmers

reached the point where they did not have food to eat or clothes to

wear. In

some places people were driven to cannibalism. More than forty million

people

starved to death during the great Mao-made famine of 1958-1962. Not

long after

Mao died in 1976, a "half-baked liberation" of the serfs took place:

farmers were given the right not to own land but to use it, unless

farmland

needed to be "developed" and it then reverted to state property. Officials

wielding the power of the state and

invoking "government ownership of land" have colluded with

businessmen all across our country .... The biggest beneficiaries of

the

resultant land deals, at all levels, have been the Communist regime and

the

power elite .... Farmers are the weakest among the weak. Without a free

press

and an independent judiciary, they have no public voice, no right to

organize

farmers' associations, and no means of legal redress .... And that is

why, when

all recourse within the system ... is stifled, people are naturally

drawn to

collective action outside the system ....

Most of the

major clashes that have broken out in China in recent years have pitted

commoners against officials. Most have occurred at the grassroots in

the

countryside, and most have been about land. Local officials, protecting

the

vested interests of the power elite, have been willing to use a range

of savage

means, drawing on government violence as well as on the violence of the

criminal underworld, to repress the uprisings. Apart from

Liu's essays dealing with injustices and various forms of criminal

abuses of

power, other articles address more general questions: for instance, the

meaning

and implications of the rise of China as a great power, still a matter

of great

uncertainty. The very rapid growth of a market economy and people's

increased

awareness of private property rights have generated enormous popular

demand for

more freedom, and this ultimately might have an effect on China's

international

position. On the other hand, the Communist government's At

home, they defend their dictatorial system any

way they can, [whereas abroad] they have become a blood-transfusion

machine for

a host of other dictatorships .... When the "rise" of a large

dictatorial

state that commands rapidly increasing economic strength meets with no

effective deterrence from outside, but only an attitude of appeasement

from the

international mainstream, and if the Communists succeed in once again

leading

China down a disastrously mistaken historical road, the results will

not only

be another catastrophe for the Chinese people, but likely also a

disaster for

the spread of liberal democracy in the world. If the international

community

hopes to avoid these costs, free countries must do what they can to

help the

world's largest dictatorship transform itself as quickly as possible

into a

free and democratic country.

Yet what

hope is there for such a transformation to take place? The regime

itself is

rigid. After more than twenty years of "reform," the only feature of

Maoist ideology that is being unconditionally retained by the Communist

Party

is the principle of its absolute monopoly over political power. There

is no

prospect that any organization will be able to muster the political

force

sufficient to bring regime change anytime soon. Liu writes: "There

is ... no sign, within the ruling elite of an enlightened figure like

Mikhail

Gorbachev or Chiang Ching-kuo, who ... helped turn the USSR and Taiwan

toward

democracy." Civil society is unable to produce in the near term a

political organization that might replace the Communist regime. In an essay

titled "To Change a Regime by Changing a Society" (also cited as

evidence in his criminal trial), Liu spells out his hopes: political

tyranny

would remain, but the people would no longer be ignorant or atomized;

there

would be a new awareness of solidarity in the face of injustice, and a

common

indignation provoked by the blatant corruption and the various abuses

of power

committed by local authorities. There would be new advances in civic

courage,

greater awareness of people's rights. Also greater economic

independence

fosters more freedom on the part of citizens to move, to acquire, and

to share

information. China

has entered an Age of Cynicism in which

people no longer believe in anything .... Even high officials and other

Communist Party members no longer believe Party verbiage. Fidelity to

cherished

beliefs has been replaced by loyalty to anything that brings material

benefit.

Unrelenting inculcation of Chinese Communist Party ideology has ...

produced

generations of people whose memories are blank .... The

post-Tiananmen urban generation, raised with

prospects of moderately good living conditions [have now as their main

goals]

to become an official, get rich, or go abroad .... They have no

patience at all

for people who talk about suffering in history .... A huge Great Leap

famine? A

devastating Cultural Revolution? A Tiananmen massacre? All of this

criticizing

of the government and exposing of the society’s "dark side" is, in

their

view, completely unnecessary. They prefer to use their own indulgent

lifestyles

plus the stories that officialdom feeds them as proof that China has

made

tremendous progress.

I know of

Western liberals who, confronted with the extreme Puritanism of the

Maoist era,

naively assumed that, after long repression, sexual liberation was bound to explode sooner or later and would

act like dynamite and open the way toward a freer society. Now an

"erotic

carnival" (Liu's words) of sex, violence, and greed is indeed sweeping

through the entire country, but-as Liu describes it-this wave merely

reflects

the moral collapse of a society that has been emptied of all values

during the

long years of its totalitarian brutalization: "The craze for political

revolution in decades past has now turned into a craze for money and

sex." anti

humane and anti moral. ... The cruel

"struggle" that Mao's tyranny infused throughout society caused

people to scramble to sell their souls: hate your spouse, denounce your

father,

betray your friend, pile on a helpless victim, say anything to remain

"correct." The blunt, unreasoning bludgeons of Mao's political

campaigns, which arrived in an unending parade, eventually demolished

even the

most commonplace of ethical notions in Chinese life. This pattern

has abated in the post-Mao years, but it has far from disappeared.

After the

Tiananmen massacre, the campaign of compulsory amnesia once again

forced people

to betray their consciences in public shows of loyalty. "If China has

turned into a nation of people who lie to their own consciences, how

can we

possibly build healthy public values?" And Liu concludes: The

inhumanity of the Mao era, which left China in

moral shambles, is the most important cause of the widespread and

oft-noted

"values vacuum" that we observe today. In this situation sexual

indulgence becomes a handy partner for a dictatorship that is trying to

stay on

top of a society of rising prosperity .... The idea of sexual freedom

did not

support political democracy so much as it harked back to traditions of

sexual

abandon in China's imperial times .... This has been just fine with

today's

dictators. It fits with the moral rot and political gangsters that

years of

hypocrisy have generated, and it diverts the thirst for freedom into a

politically innocuous direction. In a last

short piece written in November 2008, Liu looked "Behind the 'China

Miracle.''' Following the Tiananmen massacre, Deng Xiaoping attempted

to

restore his authority and to reassert his regime's legitimacy after

both had

melted away because of the massacre. He set out to build his power

through

economic growth. As the economy began to flourish, many officials saw

an

opportunity to make sudden and enormous profits; their unscrupulous

pursuit of

private gain became the engine of the ensuing economic boom. The most

highly profitable

of the state monopolies have fallen into the hands of small groups of

powerful

officials. The Communist Party has only one principle left: any action

can be

justified if it upholds the dictatorship or results in greater spoils.

Liu

concludes: In

sum, China's economic transformation, which

from the outside can appear so vast and deep, in fact is frail and

superficial.

... The combination of spiritual and material factors that spurred

political reform

in the 1980s-free-thinking intellectuals, passionate young people,

private

enterprise that attended to ethics, dissidents in society, and a

liberal

faction within the Communist Party-have all but vanished. In their

place we

have a single-barreled economic program that is driven only by lust for

profit. One month

after writing this, on December 8, 2008, Liu was arrested and

eventually

charged with "inciting subversion of state power"-whereas his only

activity was, and has always been, simply to express his opinions.

After a

parody of a trial-which the public was not allowed to attend-he was

sentenced

to eleven years in jail on December 25, 2009. (3) When, one year later,

he was

awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, Chinese authorities acted hysterically:

his

wife, his friends, and his acquaintances were all subjected to various

forms of

arbitrary detention to ensure that none of them would be able to go to

Oslo to

collect the prize on his behalf. Today his wife, Liu Xia, is in her

second year

of house arrest without charges. These dramatic measures had one clear

historical precedent: in 1935, the Nazi authorities gave the same

treatment to

the jailed political dissenter Carl von Ossietsky. (1) Two books,

actually; a similar (yet not identical) collection, in French, appeared

earlier

in 2011: Liu Xiaobo, La philosophie du

pore et autres essais, selected, translated, and introduced by

Jean-Philippe Béja (Paris: Gallimard). Since the contents of both

volumes do

not completely overlap, one would wish for a third collection that

could

combine both. For more information on Liu himself-his life, activities,

arrest,

and trial, see Perry Link, Liu Xiaobo's Empty Chair (New York Review

Books

e-book, 2011). (2 ) A new

collection of his poetry, translated by Jeffrey Yang, will be published

as June Fourth Elegies in April by

Graywolf. Additional footnotes appear in the Web version of this review

at

www.nybooks.com. (3) On December

23, 2011, the writer Chen Wei, who had been arrested in February after

posting

essays online calling for freedom of speech and other political

reforms, was

convicted of the same crime of "inciting of subversion of state

power" and sentenced, following a two-hour trial, to nine years in

prison. (4) The reader

will find that I pose a question of my own about a different country in

the

Letters section of this issue. |