|

Facing

History

Đếch khoái

trừu tượng và cực đoan, Camus bèn kiếm ra một cách, của riêng ông, để

viết về

chính trị:

thoáng, nhã, cao thượng, và hơi buồn buồn

Don Draper

of Existentialism

Tại sao

chúng ta yêu Camus.

Why we love

Camus.

Ở Mẽo,

Camus, trước hết, là 1 anh Tẩy; ở Tây, ông, quan trọng hơn hết, là 1

anh chân

đen, tức 1 anh Tây tới thuộc địa, là xứ Algeria, và làm nhà ở

đó.

Như một

nhà văn miệt vườn Mississippi, và cùng với người

đó, là 1 căn cước bí ẩn, một "Miền Nam Sâu

Thẳm", thí dụ

với Faulkner, thì với Camus, ông cũng có 1 căn cước thần bí như vậy,

hay, một

quá khứ có thể sử dụng được, một con người “Địa Trung Hải” đã từng ăn

nằm dài

dài với lịch sử biển.

Camus có cái

thứ thần bí đó: Có 1 cái gì “hoang dã” ở nơi ông, nhìn một phát là thấy

liền.

What Camus

wanted wasn't new: just liberty, equality, and fraternity. But he found

a new

way to say it. Tone was what mattered. He discovered a way of speaking

on the

page that was unlike either the violent rhetorical clichés of Communism

or the

ponderous abstractions of the Catholic right. He struck a tone not of

Voltaire

Parisian rancor but of melancholic loft. Camus sounds serious, but he

also

sounds sad-he added the authority of sadness to the activity of

political

writing. He wrote with dignity, at a moment when restoring dignity to

public

language was necessary, and he slowed public language at a time when

history

was moving too fast. At the Liberation, he wrote (in Arthur

Goldhammer's

translation):

Now that we

have won the means to express ourselves, our responsibility to

ourselves and to

the country is paramount. ... The task for each of us is to think

carefully

about what he wants to say and gradually to shape the spirit of his

paper; it

is to write carefully without ever losing sight of the urgent need to

restore

to the country its authoritative voice. If we see to it that that voice

remains

one of vigor, rather than hatred, of proud objectivity and not

rhetoric, of

humanity rather than mediocrity, then much will be saved from ruin.

Nhân nói đến

đã từng “ăn nằm dài dài với lịch sử biển.”

Nhà văn Bùi

Ngọc Tuấn vừa được giải thưởng biển lớn, của Tây, qua bản dịch tiếng

Tây tác phẩm Biển và Chim Bói Cá của ông, nhân Hội

Sách và Biển.

TV đăng lại bài cám ơn, của dịch giả, người thay mặt ông, nhận giải:

L’auteur Bùi

Ngọc Tấn est au Vietnam et regrette beaucoup de ne pas pouvoir assister

à cette cérémonie.

C’est son traducteur qui le représente. Le traducteur n’est

qu’un

exécutant, très impressionné de se trouver parmi tous ces créateurs.

C’est avec

émotion, joie et reconnaissance que nous recevons le prix décerné à

l’ouvrage, La Mer et le Martin

pêcheur. Le nous ici n’est pas de majesté, il est

simplement pluriel. Cette joie et cette émotion l’auteur me les a

exprimées

quand je l’ai eu au téléphone.

Ce prix est

pour nous une grande joie, un honneur et une consolation, parce qu’il

est la

reconnaissance internationale d’un talent mal traité dans son pays.

L’auteur a

eu de nombreux prix au Vietnam, au niveau national. Mais il a aussi

connu la prison

en raison de son talent, parce que le talent ne se soumet pas à

l’arbitraire et

à l’injustice, fussent-ils soutenus par la force.

Je remettrai

ce prix à l’auteur à mon prochain voyage au Vietnam, et nous aurons un

petite

fête avec nos amis écrivains et artistes, avec de l’alcool et du

poisson, comme

dans le roman.

Monsieur le

Président, Messieurs les membres du jury, c’est du fond du cœur, que

nous vous

disons merci.

Bản tiếng Việt

Nhà văn Bùi

Ngọc Tấn hiện đang ở Việt Nam và rất tiếc không đến dự được buổi họp

hôm nay.

Thay mặt tác giả là dịch giả. Dịch giả chỉ là người thi hành và thấy

mình thật

bé nhỏ khi đứng với bao nhiêu nhà sáng tạo.

Chúng tôi rất

cảm động vui mừng và cảm ơn nhận giải thưởng Đại Hội đã dành cho « Biển

và Chim

Bói Cá ». Chúng tôi đây không phải là lời ra oai của thiên tử mà chỉ là

đại

danh từ số nhiều. Sự cảm động và vui mừng tác giả đã biểu lộ khi được

tôi báo

tin trên điện thoại.

Giải thưởng

này là một vinh dự, một niềm vui, và là một an ủi cho chúng tôi, vì nó

là một sự

công nhận quốc tế đối với một tài năng bị bạc đãi ở chính nước mình.

Tác giả đã

từng nhận nhiều giải thưởng có tầm cỡ toàn quốc, ở trong nước. Nhưng

ông đã bị

giam cầm vì tài năng của mình. Bởi một người tài không bao giờ chấp

nhận những

điều phi lý hoặc phản công lý dù những điều đó dựa vào sức mạnh.

Tôi sẽ chuyển

giải thưởng cho tác giả khi về Việt Nam và chúng tôi sẽ có cuộc liên

hoan với

các bạn nhà văn, nghệ sĩ, có rượu và cá như đã viết trong tiểu thuyết (1)

Note:

Có 1 sự "lệch

pha" giữa bản tiếng Tây và bản tiếng Việt.

Le traducteur n’est qu’un

exécutant, très

impressionné de se trouver parmi tous ces créateurs.

Dịch giả chỉ

là người thi hành và thấy mình thật bé nhỏ khi đứng với bao

nhiêu nhà

sáng tạo.

Cùng ông, viết

hai bản văn mà đã "lệch pha", điều này cho thấy, dịch dọt rất căng,

không có phải cứ giỏi tiếng Tây mà dịch được.

GCC nghi là

ông dịch giả, ở Tây lâu quá, không rành tiếng Mít.

Từ

“exécutant” dịch là người thi hành thì cũng không "được" lắm đâu, nên

dịch là người được uỷ nhiệm thay mặt tác giả, hay đơn giản, người “thừa

hành”.

“Cérémonie”

đâu phải là… buổi họp?

Dịch “loạn”

như thế mà cũng đợp giải thưởng lớn!

Hà, hà!

Còn điều này

nữa.

BNT không phải

bị “mal traité” vì tài năng của ông, bởi vì, rõ ràng là nhà nước VC

phát cho

ông vô số giải thưởng.

Cái việc ông

ta đi tù, là do vướng tội Chống Đảng, chứ đâu phải vì ông có tài?

Bảo ông bị

đi tù vì có tài, thì quá sai, bởi vì chính là nhờ ông đi tù mà nhân đó,

hiểu rõ

hơn cái chế độ mà 1 đời ông phục vụ nó, và viết được Chuyện Kể Năm

2000, một

tác phẩm gây chấn động lương tâm Mít.

Ông ta nên

cám ơn Đảng chứ làm sao lại nói là Đảng “mal traité” ông?

Mais

il a aussi connu la prison en raison de son talent, parce que le talent

ne se

soumet pas à l’arbitraire et

à l’injustice, fussent-ils soutenus par la

force.

Nhưng

ông đã bị giam cầm vì tài năng của mình. Bởi một người tài không bao

giờ chấp

nhận những điều phi lý hoặc

phản công lý dù những điều đó dựa vào sức

mạnh.

Chưa

chắc! Thiếu gì người có tài, làm tà lọt cho cái ác?

Le vrai

Camus

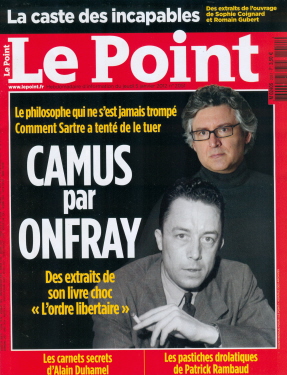

Michel

Onfray: de la grandeur de Camus

Nhà văn Bùi

Ngọc Tấn được Pháp trao giải

Note: Bài

trên BBC. Có hai lỗi, Livre de poche,

Vie de chien, [không phải en]

Don Draper

of Existentialism

Đối diện lịch

sử,

Facing History

Adam Gopnik

viết về Camus, trên The New Yorker,

April, 9, 2012

Tin động trời:

Sartre tính nhờ... Văn Cao làm thịt Camus!

Nhưng Văn Cao lúc đó, đói

lả, được Vũ Quí cho ăn bát cơm, lấy sức đi

làm thịt

tên Việt Gian Đỗ Đức Phin!

Hà, hà!

April 9,

2012 .

FACING

HISTORY

Why we love

Camus.

BY ADAM

GOPNIK

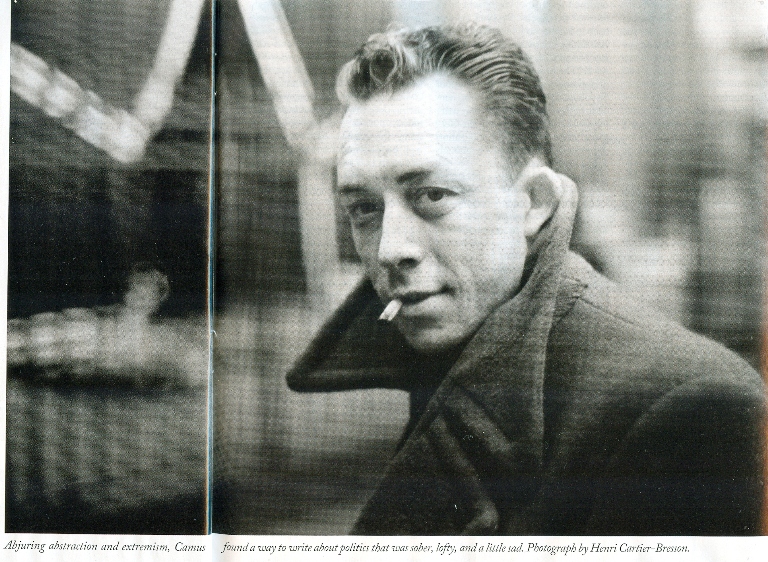

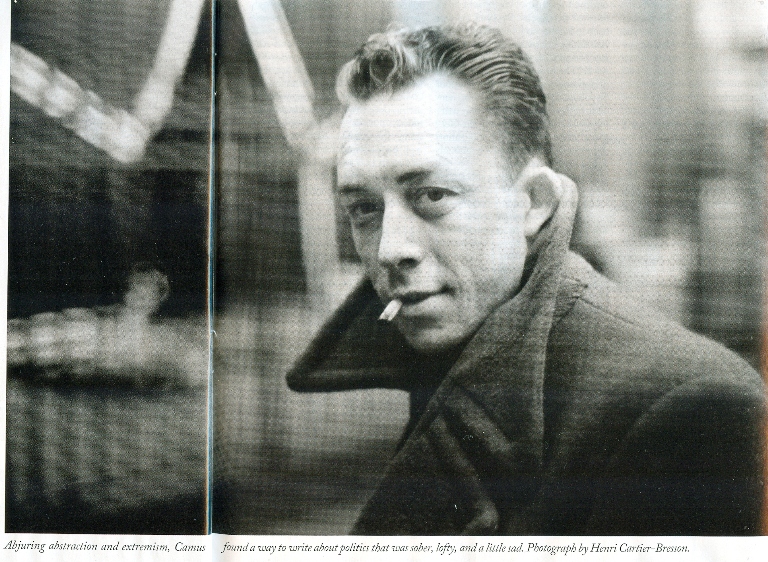

The French

novelist and philosopher Albert Camus was a terrifically good-looking

guy whom

women fell for helplessly-the Don Draper of existentialism. This may

seem a

trivial thing to harp on, except that it is almost always the first

thing that

comes up when people who knew Camus talk about what he was like. When

Elizabeth

Hawes, whose lovely 2009 book "Camus: A Romance" is essentially the

rueful story of her own college-girl crush on his image, asked

survivors of the

Partisan Review crowd, who met Camus on his one trip to New York, in

1946, what

he was like, they said that he reminded them of Bogart. "All I can tell

you is that Camus was the most attractive man I have ever met," William

Phillips, the journal's editor, said, while the thorny Lionel Abel not

only

compared him to Bogart but kept telling Hawes that Camus's central

trait was

his "elegance." (It took the sharper and more Francophile eye of A.

J. Liebling to note that the suit Camus wore in New York was at least

twenty

years out of Parisian style.)

Camus liked

this reception enough to write home about it to his French publisher.

''You

know, I can get a film contract whenever I want," he wrote, joking a

little, but only a little. Looking at the famous portrait of Camus by

Cartier-

Bresson from the forties- trench coat collar up, hair swept back, and

cigarette

in mouth; long, appealing lined face and active, warm eyes- you see why

people

thought of him as a star and not just as a sage; you also see that he

knew the

effect he was having. It's perfectly reasonable, then, that a new book

by

Catherine Camus, his surviving daughter, "Albert Camus: Solitude and

Solidarity" (Edition Olms), is essentially a photograph album, rather

than

any sort of philosophical gloss. Looks matter to the mind. Clever

people are

usually compensating for something, even if the wound that makes them

draw the

bow of art is no worse than an overlarge schnozzle and sticking-out

ears. The

ugly man who thinks hard-Socrates or Sartre-is using his mind to make

up for

his face. (Camus once saw Sartre over-wooing a pretty girl and wondered

why he

didn't, as Camus would have done, play it cool. ''You've seen my face?"

Sartre answered, honestly.) When handsome men or beautiful women take

up the

work of the intellect, it impresses us because we know they could have

chosen

other paths to being impressive; that they chose the path of the mind

suggests

that there is on it something more worthwhile than a circuitous route

to the

good things that the good-looking get just by showing up.

And then the

image of Camus persists-we recall him not just as a fine writer but as

an

exemplary man, a kind of secular saint, the spirit of his time, as well

as the

last French writer whom most Americans know something about. French

literary

critics sometimes treat him with the note of condescension that authors

of

high- school classics get here, too-a tone that the French writer

Michel

Onfray, in his newly published life of Camus, "L'Ordre Libertaire,"

tries to remedy, insisting that Camus was not only a better writer but

a more

interesting systematic thinker than Sartre.

The

skepticism of his native readers isn't just snobbish, though. Read

today, Camus

is perhaps more memorable as a great journalist-as a diarist and

editorialist-than as a novelist and philosopher. He wrote beautifully,

even

when he thought conventionally, and the sober lucidity of his writing

is, in a

sense, the true timbre of the thought. Olivier Todd, the author of the

standard

biography in French, suggests that Camus might have benefitted by

knowing more

about his anti-totalitarian Anglo-American contemporaries, Popper and

Orwell

among them. Yet in truth the big question Camus asked was never the

Anglo-American liberal one: How can we make the world a little bit

better

tomorrow? It was the grander French one: Why not kill yourself tonight?

That

the answers come to much the same thing in the end-easy does it;

tomorrow may

be a bit better than today; and, after all, you have to have a little

faith in

people- doesn't diminish the glamour that clings to the man who turned

the question

over and looked at it, elegantly, upside down.

In America,

Camus is, first of all, French; in France he remains, most of all,

Algerian-a

Franco-Algerian, what was later called a pied

noir, a black foot, meaning the European colonial class who had

gone to

Algeria and made a home there. A dense cover of clichés tends to cloud

that

condition: just as the writer from Mississippi is supposed to be in

touch with

a swampy mysterious identity, a usable past that no Northern boy could

emulate,

the "Mediterranean" man is assumed in France to be in touch with a

deep littoral history. Camus had that kind of mystique: he was supposed

to be

somehow at once more "primitive"-he was a strong swimmer and, until a

bout of tuberculosis sidelined him, an even finer football player-and,

because

of his Mediterranean roots, more classical, in touch with olive groves

and Aeschylus.

The reality was grimmer and more sordid. His father, a poorly paid

cellar man

for a wine company, was killed in battle during the First World War,

when Camus

was one. His mother was a maid, who cleaned houses for the healthy

French

families. Though he was, as a young man, sympathetic to Algerian

nationalism,

he understood in his marrow that the story of colonialist exploitation

had to

include the image of his mother on her knees, scrubbing. Not every

colonial was

a grasping parasite. Camus was a first-rate philosophy student, and the

French

meritocratic system had purchase even in the distant province. He

quickly

advanced at the local university, writing a thesis on Plotinus and St.

Augustine when he was in his early twenties. After a flirtation with

Communism,

he left for the mainland in 1940, with the manuscript of a novel in his

suitcase and the ambition to be a journalist in his heart. He worked

briefly

for the newspaper Paris-Soir, and

then returned to North Africa, where he finished two books. By 1943, he

was

back in France, to join the staff of the clandestine Resistance

newspaper Combat, and publish those books: first

the novel "The Stranger" and then a book of philosophical essays,

"The Myth of Sisyphus." Part of the paralyzing narcotic of the

Occupation was that writing could still go on; it was in the Germans'

interest

to allow the publication of books that seemed remote enough not to be

subversive.

The novel

and the essays announced the same theme, though the novel did it on a

downdraft

and the essays on up- lift: meaning is where you make it and life is

absurd. In

the novel, Camus meant absurd in the sense of pointless; in the essays

in the

sense of unjustified by certainty. Life is absurd because Why bother?

And life

is also absurd because Who knows? "The Stranger" tells the story of

an alienated Franco- Algerian, Meursault, who kills an Arab on the

beach one

day for no good reason. The no-good-reason is key: if it's possible to

act for

no good reason, maybe there is never any reason to talk about "good"

when you act. The of world is absurd, Meursault thinks (and- Camus

seconds),

because, without divine order, or even much pointed human purpose, it's

just

one damn thing after another, and you might as well be damned for one

thing as the

next: in a world bleached dry of significance, the most immoral act

might seem

as meaningful as the best one. The drained, eye-straining beach where

Meursault

murders his victim is a place not just without meaning but without real

feeling-it became the deadened landscape, and the cityscape, that was

populated

in the decade by everyone from Giacometti's emaciated walking figures

to

Bogart's private eyes.

In

"Sisyphus," though, Camus offers a way to keep Meursault's absurdity

from

becoming merely murderous: we are all Sisyphus, he says, condemned to

roll our

boulder uphill and then watch it roll back down for eternity, or at

least until

we die. Learning to roll the boulder while keeping at least a half

smile on your

face-"One must imagine Sisyphus happy" is his most emphatic aphorism-is

the only way to act decently while accepting that acts are always

essentially

absurd.

It was the

editorials that Camus wrote for Combat

that sustained his reputation. Editorial writers can seem the most

insipid and

helpless of the scribbling class: they sum up anonymously the ideas of

their

time, and truth and insipidity do a great deal of close dancing-the

right thing

to do is often hard but seldom surprising. Good editorial writing has

less to

do with winning an argument, since the other side is mostly not

listening, than

with telling the guys on your side how they ought to sound when they're

arguing.

It's a form of conducting, really, where the writer tries to strike a

down- beat,

a tonic note, for the whole of his section. Not "Say this!" but

"Sound this way!" is what the great editorialists teach.

What Camus

wanted wasn't new: just liberty, equality, and fraternity. But he found

a new way to say it. Tone was what mattered. He discovered a way of

speaking on

the page that was unlike either the violent rhetorical clichés of

Communism or

the ponderous abstractions of the Catholic right. He struck a tone not

of

Voltaire Parisian rancor but of melancholic loft. Camus sounds serious,

but he

also sounds sad-he added the authority of sadness to the activity of

political

writing. He wrote with dignity, at a moment when restoring dignity to

public

language was necessary, and he slowed public language at a time when

history

was moving too fast. At the Liberation, he wrote (in Arthur

Goldhammer's translation):

Now

that we have won the means to express

ourselves, our responsibility to ourselves and to the country is

paramount. ...

The task for each of us is to think carefully about what he wants to

say and

gradually to shape the spirit of his paper; it is to write carefully

without

ever losing sight of the urgent need to restore to the country its

authoritative

voice. If we see to it that that voice remains one of vigor, rather

than hatred,

of proud objectivity and not rhetoric, of humanity rather than

mediocrity, then

much will be saved from ruin.

Responsibility,

care, gradualness, humanity-even at a time of jubilation, these are the

typical

words of Camus, and they were not the usual words of French political

rhetoric.

The enemy was not this side or that one; it was the abstraction of

rhetoric

itself. He wrote, 'We have witnessed lying, humiliation, killing,

deportation,

and torture, and in each instance it was impossible to persuade the

people who were

doing these things not to do them, because they were sure of

themselves, and

because there is no way of persuading an abstraction." Sartre, in a

signed,

man-en-the-scene column for Combat,

wrote that the Liberation had been a "time of intoxication and joy."

(Actually,

Sartre kept off the streets and let Simone de Beauvoir do the writing,

while he

took the byline.) Intoxication and joy were the last things that Camus

thought

freedom should bring. His watchwords were anxiety and responsibility.

It was in

the forties that Camus became intimate with Sartre. Though each had

known the other's

writing before meeting the writer, they became friends, in

Saint-Germain, in 1943,

a time when the Cafe de Flore was not an expensive spot but one of the

few

places with a radiator reliable enough to keep you warm in winter. For

the next

decade, French intellectual life was dominated by their double act.

Although

Camus was married, and soon afterward had a mistress, and soon after

that had twins

(by his wife), an American reader of Todd's biography is startled to

realize that

after the twins were born Camus's life went on exactly as before-hi's

deepest

emotional attachment seems to have been to Sartre and his circle.

Indeed, the

image of the French philosophers in cafes debating existentialism dates

from

that moment and those men. (Before that, Frenchmen in cafes debated

love.)

Philosophers?

They were performers with vision, who played on the stage of history.

Their

first conversation was about the theatre-Sartre asked Camus,

impulsively, to direct

the coming production of his play "No Exit"-and not long afterward

Sartre was sent, by the Resistance unit he had belatedly joined, to

occupy the

Comedie-Francaise. (The Resistance actually had a theatre committee.)

Camus came into the theatre and found Sartre asleep in an orchestra

seat.

"At least your armchair is facing in the direction of history," Camus

teased him, meaning that the chair looked more committed than the

sleeping

philosopher.

The

wisecrack bugged Sartre more than he first let on, as such jokes will

among

writers. Sartre-bashing has become a favorite sport for Anglo-American

intellectuals-in

the past decades, Clive James and the late Tony Judt have both kicked

him

around-and so it's worth recalling why Camus valued Sartre's good

opinion more

than anyone else's. Sartre's appeal was, in no small part, generational

and

charismatic. If you had asked people whose lives Sartre changed why

they

admired him so keenly, they would have said that it was because in his

book

"Being and

Nothingness," and in the famous 1945 speech "Existentialism Is a

Humanism,"

he had reconciled Marxism and existentialism. To some, this may seem

like not

much of an accomplishment-they may feel rather as a parent feels when a

child

has, over breakfast, reconciled Lucky Charms and Froot Loops in one

bowl-but at

the time it

seemed life-giving. Sartre had found a role for both humanism and

history- "humanism"

meaning the Enlightenment

belief that individual acts had resonance and meaning, "history"

meaning the Marxist belief that, in the impersonal working out of the

dialectic,

they actually didn't. Sartre said that you couldn't know how history

would work

out, but you could act as if you did: "If I ask myself “Will the social

ideal, as such, ever become a reality?” I cannot tell I only know that

whatever

may be in my power to make it so, I shall do; beyond that, I can count

upon

nothing." And again: "Man is nothing else but what he purposes, he

exists only in so far as he realizes himself, he is therefore nothing

else but

the sum of his actions, nothing else but what his life is." (There are

moments when Sartre sounds like Tony Robbins-only you can

make you what you want to be! - which may also have been,

secretly, part of his appeal.) People aren't born free and everywhere

are in

chains; they're just born. What better way to choose freedom than by

unlocking

the next guy's chains, too?

Sartre's

move toward Marxism, and toward the French Communist Party, oddly

mimicked that

of the French philosopher Blaise Pascal's seventeenth-century "wager"

in favor of Christianity: the faith might be true, so why not embrace

it, since

you lose nothing by the embrace, and get at least the chance of all the

goodies

the faith promises? In Sartre's case, if the "social ideal" never

arrived, at least you had tried, and if it did you might get a place in

the

pantheon of proletariat heroes. This reasoning may seem a little shabby

and

self-interested, but to those within Pascal's tradition it seemed brave

and

audacious. (Camus called Pascal "the greatest of all, yesterday and

today.") Faith in the Party, which Sartre never joined but to which he

gave his purposefully blind allegiance, so closely mirrored faith in

the Church

that it borrowed some of the Church's residual aura of moral purpose.

It wasn't

that Sartre didn't notice the Soviet camps. He did. He just thought

that you

could look past them, as a good Catholic doesn't pretend not to see the

Hell on

earth that the Church often has made but still thinks you can see the

Heaven

beyond that it points to.

Camus moved

toward a break with Sartre, and Sartre's magazine, Les Temps Modernes,

in 1951,

after the publication of his "L'Homme Revolte," called in English, a

little misleadingly, "The Rebel." The fault line between the two men

was simple, if the fault-finding was complex. Sartre was a straight-out

fellow-traveler

with the P.C.F., the Parti Communiste Francais, and Camus was not.

Sartre was

outraged on behalf of the Party by such episodes as the "affair of the

carrier pigeons," in which the Party Secretary was found with pigeons

in

his car and was accused by the police of using them, like a good

revolutionary,

to coordinate illegal demonstrations. (It turned out that, like a good

Frenchman, he was merely planning a squab casserole.) In "The Rebel,"

Camus writes (in Philip Mairet's translation):

He

who dedicates himself to the duration of his

life, to the house he builds, to the dignity of mankind, dedicates

himself to

the earth and reaps from it the harvest that sows its seed and sustains

the

world again and again. Finally, it is those who know how to rebel, at

the

appropriate moment, against history who really advance its

interests.

In English,

this can come across as merely sonorous. In France in 1951, the real

meaning

was barbed and apparent: only a moral idiot would give his allegiance

to the

Communist Party in the name of the coming revolution. Camus spotted

"the

catch in Sartre's account of fellow-travelling as a leap of faith. The

only

practical way to unlock the next guy's chains, on Sartre's premise, is

to kill

the guy next to that guy first, since he's the one chaining him up;

kill all

the jailers and everyone will be free. This sounds great, Camus saw,

until

you've killed all the jailers and all you have is other jailers. There

is no

difference between dying in a Soviet camp and dying in a Nazi camp. We

should

be neither executioners nor victims; it is madness to sacrifice human

lives

today in the pursuit of a utopian future.

This

position was rightly praised for its truth and oddly praised for its

courage.

After all, opposition to both Fascism and Stalinism was exactly the

position of

every democratic government in North America and Western Europe. It was

Harry Truman's

position and it was Clement Atlee's position; it was Winston

Churchill's

position and Pierre Mendes-France's. It was the doctrine of the liberal

version

of the Cold War: the true inheritors of "totalitarianism" were the

Communists, and had to be resisted.

Well, it was

courageous, we say, because, though common people and politicians were

wiser,

intellectuals in France believed the opposite. This is not false, but

there is

a subtler point at play. It is in the nature of intellectual life-and

part of

its value-to gravitate toward the extreme alternative position, since

that is

usually the one most in need of articulation. Harvard and Yale pay some

of

their professors to tell the students that everything they believe is a

bourgeois illusion, as the Koch brothers pay their foundation staff to

say that

all bourgeois illusions are real, and the fact that neither is entirely

true

does not alter the need to pay people to say it. The ideas we pay for,

as Ayn

Rand grasped when she looked at her royalty statements, are those which

define

the outer edge. We want big minds to voice extreme ideas, since our

smaller

minds already voice the saner ones.

In this

sense, Sartre's admirers are not wrong when they protest what seems to

them the

naive moralizing of his Anglo-American critics. Those admirers, who

remain

plentiful in Paris, insist that Sartre was, above all, open-minded,

that

he reproached himself for his own errors, constantly revised his

mistakes,

broke with the Soviets not all that long after siding with them-that

his

open-ended, lifelong "recherche" was never meant to be concluded, and

that you shouldn't score it like a foot- ball match, Right Views 3,

Wrong Views

6. To accuse such a thinker of hypocrisy seems unfair, but

perhaps he can be

accused of too much habitual happiness. For all their self-advertised

agonies,

the lives Sartre and Camus led after the war mostly sound like a lot of

fun. Their

biographies are popular because they dramatize the agonizing

preoccupations of

modern man and also because they present an appealing circle of Left

Bank cafes

and late-night boites and long

vacations. A life like that implicitly assumes that the society it

inhabits

will go on functioning no matter what you say about it, that the cafes

and

libraries and secondhand bookstores will continue to function despite

the

criticism. A professor at the College de France who maintains that

there should

be no professors at the College de France does not really believe this,

or else

he would not be one.

This wasn't

a luxury that thinkers in Moscow, much less Phnom Penh, ever had.

Sartre's

great sin was not his ideology, which did indeed change all the time.

It was

his insularity. The apostle of ideas as action didn't think that ideas

would

actually alter life; he expected that life would go on more or less as

it had

in spite of them, while always giving him another chance to make them

better.

Nice work, if you can get it.

Camus wanted

a better Republic. What he got was the Fourth Republic. De Gaulle is

often

given credit for the myth of the Resistance, which is no more of a myth

than

the American myth of emancipation; i.e., it really did happen, you just

have to

leave a lot of other stuff out to make what happened sound like it was

mostly good.

But he also created another myth: that of the failure of the Fourth

Republic,

in order to prove the necessity of his Fifth. In fact, the Fourth

Republic, far

more parliamentary than the Presidential-monarchical Fifth, was no more

than

normally corrupt and inefficient, and did a terrific job of moving

France from

paralysis to prosperity from 1945 to 1958. It foundered exactly on the

insoluble problems of decolonization, about which it could be no wiser

than its

constituent parts.

Along the

way, it solved philosophical problems. It may be hard to reconcile

history and

humanism, but it isn't hard to make laws that force capitalism to give

workers

more rights and comforts and security than they had before, while still

respecting the liberty of each man to run a small shop and curse the

government. It's so easy that every wealthy Western country has done

it, and

was doing it, even as its masterminds were arguing about whether it

would ever

be imaginable. These things are easier to do than they are to think

about-a

Sartrean point that Sartre never quite got around to seeing.

Sartre

responded to "The Rebel" with truly papal exquisitism. Rather than

let the condemnation of the heretic come from the seat of Peter, it

would come

from lower down, which would both imply a certain papal ambiguity and

allow the

possibility of reproach and an eventual welcome home. The task of

condemning

Camus was handed to a staff writer for Les Temps Modernes named Francis

Jeanson,

who went after Camus full tilt, praising his prose style (praising a

writer's

smooth prose is usually a way of implying that he's not too bright

about the

big ideas) and accusing him of being both a philosophical naïf and an

unwitting

tool of the French right. Camus, replying, ignored Jeanson completely,

and

directed his words exclusively to Sartre, as the "Director of the

Publication." Sartre, replying in turn, tried to play the innocent:

Jeanson wrote that, not me; by writing to me, you dehumanize Jeanson.

In this way,

Sartre both protected and belittled Jeanson, implying that he was in

need of

papal protection, and accused Camus of indifference to the little

people Sartre

was at that moment belittling. It was a neat job. (Jeanson, as it

happens, was

a genuinely interesting character, more Catholic than the Pope, and

even more heretical than the heretic, and has recently received a good

biography by Marie-Pierre Ulloa. While Sartre was far too comfortable

and

cunning to be any kind of example of Sartrean man, and Camus far too

touched by

inner rectitude to be an instance of Camusean man, Jeanson was both. A

partisan

of the Algerian rebels, he ended up, poor guy, in hiding for almost a

decade,

far from Saint-Germain-the only man in the circle who thought they

meant it.)

Each man

knew where the other was vulnerable. Calling Sartre "Monsieur le

Directeur," that is, a kind of literary bureaucrat, was Camus's dig at

his

friend's position; Sartre countered by condescending to Camus's

philosophical

pretensions. "And sup-pose you didn't reason very well? And suppose

your

thinking was muddled and banal?" he suggested. Infuriated, Camus chose

to

remind Sartre of the nap at the Comedie-Francaise, saying that, as a

militant

who had "never walked away from the combats of the time," he was

tired of being given lessons by those who had "never placed more than

their armchairs in the direction of history." Like the word "upstart,"

which makes Groucho declare war in "Duck Soup," "armchair"

was the fatal insult. The two men never spoke again.

Wounded by

the exchange, Camus was silenced by the Algerian war. Sartre saw the

world's

crisis on a North-South, not an East-West, axis. The Soviet domination

of Europe,

and the fellow-travelling acquiescence of the French Communist Party in

that

domination-indeed, its explicit

desire to extend it to Western Europe-might have been, perhaps should

have

been, Sartre's central subject. But his preoccupation was instead the

wars of

colonial empire that dominated French foreign policy throughout the

fifties,

first the war in Indochina and then the one in Algeria, with Suez in

between.

To see the central political story of the fifties as the attempt by the

Western

democracies to hold on to their liberty is rational; but to see it as

the attempt

by the fading European empires to hold on to their overseas possessions

is not

false, either, and recedes for us in memory only because it failed so

completely that we don't even remember that they tried.

Though

impeccably anti-colonial, Camus refused to take part in the sentimental

embrace

of the National Liberation Front, the F.L.N. that became de rigueur in

left-wing circles in those years. Struggling to explain why he could

not

abandon the idea of a French Algeria-or, at a minimum, of some decent

compromise that would insure majority rule while protecting the rights

of the

"settler" minority-he ended with the weak-sounding formula that he

could not abandon his mother, which made it seem merely a question of

blood.

Lacking a better way of putting it, he chose silence, and this most

indispensable of editorialists spent the last five years of his life,

until his

death, in a car crash, in 1960, with his own tongue under house arrest,

vowing

not to speak about the Algerian problem.

Camus felt

as deeply for the seeming oppressor as for the oppressed. He grasped

that the

great majority of the settlers in any country, and in Algeria in

particular,

were as much victims of the circumstance as the locals, and made the

same

claims on decency and empathy. They were for the most part not rootless

colonists who had come for the main buck-and those who were would be

replaced

by a local boss class. Colonialism is wrong, but the human claims of

the

colonists are just as real as those of the colonized. No human being is

more

indigenous to a place than any other. This remains an unfashionable,

even

taboo, position; one feels it still, for instance, in the condescension

that

American leftists offer white South Africans. (Athol Fugard's plays are

a good

antidote for his simplification, while Mandela's moral greatness was to

see,

and say, that the Boers were as much South Africans as the Xhosa.)

Camus wasn't

wrong. What he meant by his mother was his mother: not blood loyalty or

genetic

roots but the particular experience of a woman who had labored all her

life as

a domestic servant and was no more guilty of or complicit in colonial

crimes

than everyone else who lives on earth is complicit in dispossessing

someone. It

wasn't that he wouldn't abandon his roots for a cause; it was that he

wouldn't

abandon his mother for an idea.

Camus called

the tendency to dehumanize those who stood in the way of history the

problem of

"abstraction." He meant that we can always look past the humanity of

the kulaks or the pieds noirs or

whoever is the necessary victim of the day. Read too much Marx, and

you'll look

right past your own mom. What's a few hundred thousand peasants in the

face of

history? Camus thought that all systems of ideal government were wrong,

and all

atrocities equally atrocious. To be a liberal in that sense, with a

style that conferred

eloquence on compromise, was the accomplishment. When Sartre's circle

praised

Camus's style and then objected to it, they were on to something. The

threat he

posed to totalitarian thought came from his ability to attach these

common-sense principles to a set of magisterial arguments and timeless

aphorisms. There is no better book to read for moral salt and sweetness

than

his notebooks from the fifties, which are filled with chiselled

epigrams:

"Progress-minded intellectuals. They are the tricoteuses

of the dialectic. As each head falls, they reknit the

sleeve of reasoning torn apart by the facts." Or simply: "Justice in

the big things only. For the rest, just mercy."

Liberalism

is optimistic in English- speaking countries, and therefore always a

little

fatuous. Telling Sisyphus that he'll get that stone up there someday is

an

empty hope. He won't. Camus imagined Sisyphus committed to his daily

act; he

doesn't encourage him to hope for a better stone and a shorter hill.

The

counsel given is essentially the same-short-term commitment to the best

available course of action-but, by accepting that the boulder is always

going

to roll back down, Camus put a tragic mask on common sense, and a

heroic face

on the daily boulder's daily grind. It may have been the handsomest

thing he ever did .•

THE NEW

YORKER, APRIL 9, 2012

|

|