|

Vẫn chuyện

phê bình, điểm sách, do nhà văn, tiểu thuyết gia viết. GCC đọc

Mantel mới đây thôi, sau khi bà đoạt liền tù tì hai Booker Prize, hai

cuốn tiểu

thuyết,

cùng đề tài, cùng 1 dạng, tiểu thuyết lịch sử.

The New York Review of

Books In 2013, The

New York Review of Books celebrates its fiftieth anniversary. During

the course

of the year we will reprint excerpts from other notable pieces

published in the

Review over the last five decades. For news and

features about the fiftieth anniversary, visit www.nybooks.com/50.

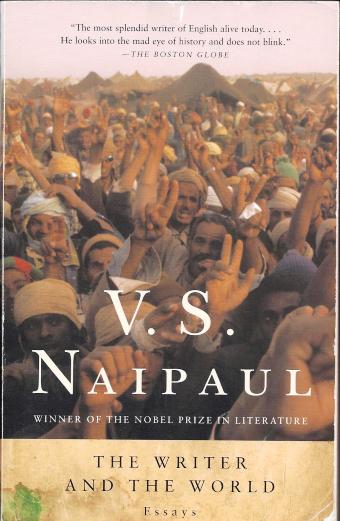

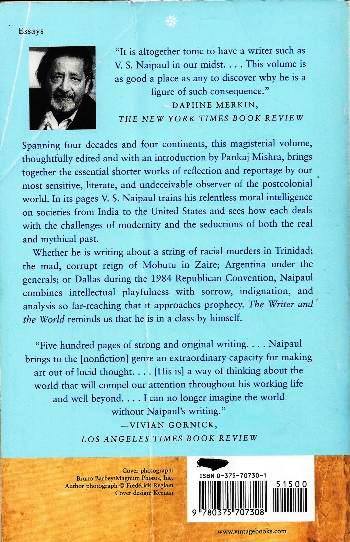

Naipaul's

Book of the World Hilary

Mantel Hilary

Mantel has contributed over forty reviews and works of fiction to The New York Review since

1989.

The following is an extract from "Naipaul's Book of the World," a

review of V. S. Naipaul's The Writer and the World. It

appeared

in the October 24,2002, issue and may be There are

places on earth where, at certain moments in the cycle of day and

night, the

two are indistinguishable. It is impossible to know, without other

referents,

whether you are looking at dawn or dusk. And there are places at the

margins of

cities, or at the edges of the man-made sprawl of holiday islands,

where at

twilight growth and decay are indistinguishable; you can't tell, at

first

glance, whether you are looking at a building site or a ruin. Is that

earth-colored brick waiting for its glassy marble cladding, or is it

crumbling

back into the condition of soil? And that distant rumble, of traffic or

marching feet: Have the entrepreneurs arrived, or is it the barbarians?

Is it

possible that they are the same? Instances of crepuscular insight,

coupled with

the qualms of self doubt, are for the privileged but disinterested eye;

they

come more readily to the artist than to the politician or the aid

worker or the

hard-hated man driving a digger into the jungle. You have to pick your

place to

stand, and work by the light of informed intellect, before you can

judge

whether social institutions or indeed whole societies are accreting

meaning or

leaking it away. Over forty years of

traveling and writing, V. S. Naipaul has

made himself both a judge and an expert witness in the topography of

"half- made societies." Visiting India in 1962, he saw "towns

which, even while they develop, have an air of decay." Montevideo in

1973

is a "ghost city" mimicking European glories. It is populated by

statues and the figures of historical tableaux cast in bronze, but

their inscriptions,

with individual letters fallen away, are becoming indecipherable. The

shops are

empty but street vendors crowd the sidewalks. The restaurants have no

meat.

Public clocks have stopped. As colonizers pack their

bags and dream cities dissolve, the

bush is always waiting to creep back. Tenderness toward the bush is an

emotion

only the secure can feel. Only those who are free to leave them can be

sentimental about the wild places of the earth. The bush is a recurrent

conceit

in Naipaul's work. It has "its own logical life," but it is a logic

that leads nowhere, except into the self-serving thickets of

irrationality. It

is the place where the social contract breaks down; it represents not

just the physical

encroachment of nature but the proliferating undergrowth of the human

psyche. From the first, Naipaul's

sardonic and fastidious approach

distinguished him from those who write about the underdeveloped world

in eggshell

pieties. He has a sharp eye for the intellectually fraudulent, and is a

scourge

of self-delusion; he gives the underdog as bad a name as his master.

Oppression, he notices, doesn't make people saintly, it makes them

potential

killers; all victims are dangerous. On the one hand he has been accused

of contempt

for peoples of the third world; less liberal readers have embraced him

as a

sort of projection of themselves, more derogatory about developing

countries

than they would ever dare to be, his color and ethnic background

excusing him

from the obloquy they would attract if they expressed the same distaste

and

unease. * One reason

to welcome the present volume is that a gap has opened, over the years,

between

what Naipaul has written, what people think he has written, and what

they feel

he ought to have written. His asides are often more pessimistic than

the body

of his work, and his dogmatic pronouncements in interviews-"Africa has

no

future"-contrast with the subtlety of thought and expression in his

written pieces. He writes with delicacy and compassion about individual

lives,

and much of the work in this collection employs a calm perspective that

his

detractors often miss. And yet, there is no respite from the Naipaul

personality,

ferociously intelligent and permanently aggrieved. As a travel writer he

knows journeys are to be endured, not

enjoyed. They look glamorous only in retrospect. Most people's

journeys, in the

course of history, have not been voluntary. Transportation, slavery,

and forced

migration have taken more people away from their birthplace than has

the desire

for novelty. Naipaul is spiritually among them, as remote from the

tourist

mentality as he is from the mind-set of those travelers who get into

trouble

only to feel smug on getting out of it. He is at all times anxious

about his

own person- the witness, after all, must be preserved-and his faculty

of

physical disgust is highly developed. Given the chance, he heads

straight for the nearest international

hotel. He knows that the unfamiliar need not be sought, for it comes to

find

you; for the nervous man, familiarity can be destroyed by a walk into

the next

room. The real undiscovered country is other people, human beings in

all their singularity.

He lets them speak and shape his narrative for him, and his respect for

their

stories is far removed from the misanthropy with which he is sometimes

taxed. It

is true that he has a dread of the flamboyant and the willfully

eccentric:

"I recognized her as a 'character," he says, warily eyeing the

manageress when checking into the only hotel in Anguilla that has

electricity.

"Characters lie on my spirit like lead." * Fastidious

in his person as in his intellect, Naipaul is a puritan in matters of

style. It

is the sparseness of his effects, his exactness, which transfixes the

reader.

Naipaul's contempt for "fine writing" is clear. He cultivates

plainness, so that his actual words are seldom remembered by the

reader; what

lingers is their authoritative rhythm, an impression of discrimination

and scruple,

of wit and restraint. "I work with very strong emotions," he has

said, "and one's writing is a refining of those emotions." With

Naipaul,

style is substance. Each sentence pounces on its meaning, neat as a

cat. Each

paragraph has attack, dash, élan. There are no jokes, no whimsy; there

is no descent

to the demotic, no bravura display. What has been important to

Naipaul throughout his career is

to make a relationship with language that is clean, unflawed, fit for a

man who

has had to write himself into being. It is a common experience of

expatriates

and travelers that, when you meet someone from another culture, you

begin to

act out a part you feel you have been assigned in an earlier life. Your

persona

goes into action, and you deliver the lines provided by some mysterious

central

scripting unit. But there was no one to provide Naipaul with lines. He

has had

to write his own. He has represented no one but himself, spoken for no

one but

himself, and spoken in no one else's language. He seems impervious to

the influence

of systems, just as he is unaltered by changing fashions in writing.

You sense

that the curve of evolution in his own work comes from within himself

and is

something he alone fully understands. Perhaps what we will say

about Naipaul was that he was the

self-made man who didn't stop at weaving the cloth for his own garments

but

clothed his own bones in prose. We will say he was the rational man who

was

afraid to see night fall, because it falls within himself. His shining

belief

in order and progress is stained by an area of internal darkness: by a

natural apprehension-though

not a certainty-that the power of reason will be defeated. "The aim has

always

been to fill out my world picture, and the purpose comes from my

childhood: to

make me more at ease with myself." To our profit, this is the

one aim he has missed. His readers

may complain that they are trapped in an enactment of his own

psychodrama, but

the point is that it is not simply his own; we are all afraid of the

dark, and

though Naipaul is an isolate, he is not a solipsist. The narrator of

the novel

The Enigma of Arrival writes, "To see the possibility, the certainty,

of

ruin, even at the moment of creation; it was my temperament." Naipaul's

myth is that of the artist who has suffered more from his art than his

life,

more from his interpretations of reality than from reality itself. He

is the

person most haunted by what he has rejected, by the childhood he has

cast off,

by the private fear he has made into a universal condition. Wherever he

goes,

he is sailing the inland sea. +

|