BACK in 2007, the prize-winning Irish writer, Colm Toibin, told a press conference that the most interesting writer he had come across in two years of reading contemporary fiction as a judge of that year’s Man Booker International prize was Laszlo Krasznahorkai, a reclusive Hungarian with a reputation for sentences so long and convoluted that some of them went on for an entire chapter.

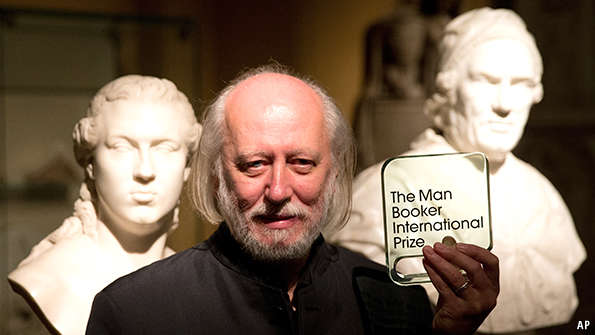

So impressed was Mr Toibin by the Hungarian’s fabulist confections that he founded a small publishing imprint, Tuskar Rock Press, to bring just such fiction to a wider audience. Eight years on, Mr Toibin’s faith in Mr Krasznahorkai’s talent has been vindicated. Just after Tuskar brought out his latest book, “Seiobo There Below” in Britain, the Hungarian novelist was named the winner of the Man Booker International prize for 2015. Now ten years old, the prize, the winner of which was announced on May 19th, differs from the annual Man Booker prize for fiction in that it is awarded every two years, and for a body of work rather than a single book.

This novel of 17 stories brings together a series of artists—the Italian Renaissance painter Perugino in his workshop, a Japanese Noh actor rehearsing—and ordinary people who are trying to grasp what sacred means or understand what beauty, art and transcendence might look like. Mr Krasznahorkai’s sentences worry at these eternal questions, picking and unpicking tiny details, actions and reactions, in a relentless attempt both to pin down and describe the complexities of contemporary life.

The Hungarian is, of course, not the first modernist to manhandle prose and use the sentence as instrument. But even more than Thomas Bernhard or W.G. Sebald, he winds and unwinds and rewinds, creating what one translator has described as “a slow lava-flow of narrative, a vast black river of type”, which along the way acquires a transcendent quality of its own. The stories in “Seiobo There Below” are arranged according to the Fibonacci mathematical sequence, with each one as long as the two previous ones, which adds to the reader’s sense of being on a journey. As always with Mr Krasznahorkai, real understanding remains beyond mortal grasp, though a sense of illumination is pervasive. As a novelist he is a one-off, even if his work—as this book so finely shows—is universal.