|

Writers who spiedThe unsurprising link between authorship and espionage

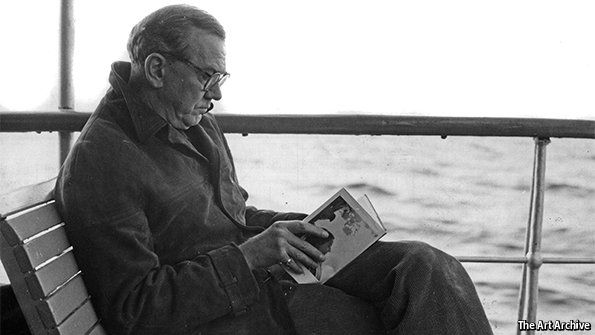

“CHAMPAGNE, if you are seeking the truth, is better than a lie detector,” Graham Greene (pictured above) wrote in “Ways of Escape” (1980). “It encourages a man to be expansive, even reckless, while lie detectors are only a challenge to tell lies more successfully.” Greene sought the truth in the people around him for the sake of his writing, but one can’t read this reflection without wondering how it was informed by his involvement in another kind of lie detecting. When he wasn’t writing (and sometimes when he was), Greene worked as an agent for MI6, the British intelligence service. Greene was recruited in 1941, after he had already established his career as a writer. It was a credible cover for intelligence gathering and his penchant for traveling to certain significant regions for his novels—Liberia, Mexico, Haiti, Cuba, Vietnam—made him a valuable informant. Spying had the added perk of offering Greene intriguing material. Some of his books, like “Our Man in Havana” (1958) and “The Quiet American” (1955), feature spies directly, but the relationship between writing and spying goes deeper and is more intriguing. Greene, who died 25 years ago this month, was by no means the first novelist to experiment with espionage. When Cambridge hesitated to award Christopher Marlowe his degree due to frequent absences, Queen Elizabeth I’s Privy Council explained that he was working “on matters touching the benefit of his country.” Marlowe is thought to have been recruited by Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth’s spymaster. He died under mysterious circumstances at age 29, stabbed in a tavern brawl in the company of other Walsingham acquaintances. Ian Fleming and John Le Carré’s careers in British intelligence are well known, but less obvious figures were recruited too. Roald Dahl served as a spy from Washington. Peter Matthiessen joined the CIA out of Yale. The Paris Review, an esteemed literary magazine, was born—somewhat scandalously—out of Matthiessen’s intelligence duties: “I needed more cover for my nefarious activities, the worst of which was the unpleasant task of checking on certain Americans in Paris to see what they were up to. My cover, officially, was my first novel, but my contact man… had said, ‘Anything else you can do while you’re here?’” Ernest Hemingway (pictured below) had contacts in American intelligence agencies as well as the Soviet Union’s NKVD, the predecessor to the KGB. He gathered intelligence with a French resistance group during the second world war. He patrolled the Caribbean in search of German submarines. He wasn’t particularly successful, but he seems to have enjoyed the game. According to declassified documents, Hemingway’s concept of operations was to “pretend to be fishing, wait until a German submarine came alongside to buy fresh fish and water, and then attack the enemy with bazookas, machine guns, and hand grenades.” The Soviets later recruited him “for work on ideological grounds”, and codenamed him “Argo”. Perhaps they hoped he would report on prominent Americans—he had notable contacts—or influence public opinion through his writing. It is not so surprising that so many writers have worked in intelligence. Writers create plots; spies uncover them. In a sense, all writers function like spies—observing the people around them, studying character types, becoming flies-on-the-wall for the purpose of their art. “Everything is useful to a writer,” Greene insisted. “Every scrap, even the longest and most boring of luncheon parties.” Writers are obsessed with plot and character, motive and perspective, and with the space between interior and exterior worlds, between what people think and what they say. Mr Le Carré has suggested that espionage is a kind of metaphor; we all live undercover and mask our private selves with projected social personalities. “Most of us live,” he said, “in a slightly conspiratorial relationship with our employer and perhaps with our marriage.” Writing is a means of decoding experience, of piercing through the surface of things to get at the truths beneath. Hemingway, in particular, was obsessed with the idea of concealment—so much so that he embedded it in his very style of writing. His famous minimalism derives from his “iceberg theory,” the principle that a writer should keep seven-eighths of a story beneath the surface—unspoken but implied. “The dignity of an iceberg,” Hemingway wrote, “is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.” When this was done well, he believed the reader would “have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them”. By representing only the bare tip of a story, without exposition or more revealing dialogue, he sought to mirror in fiction the concealment and uncertainty we experience in the world. Hemingway—like all writers—intended his reader to uncover the truth he submerged, to dig below the surface clues of the text. In this way, authors extend the reconnaissance game, setting down their webs of meaning for readers to unravel. The best spy-writers leave us with the sense that the whole world is a vast text to be deciphered, but they caution about deciphering too. In the world of espionage, as in the real world, the greatest tragedies and failings are often matters of misinterpretation. Of the CIA spy, Alden Pyle, Greene’s narrator in “The Quiet American”, observes, “I never knew a man who had better motives for all the trouble he caused.”

|