|

NOTHING ELSE

Friends of the small hours of the night: Stub of a pencil, small notebook, Reading lamp on the table, Making me welcome in your circle of light. I care little the house is dark and cold With you sharing my absorption In this book in which now and then a sentence Is worth repeating again in a whisper. Without you, there'd be only my pale face Reflected in the black windowpane, And the bare trees and deep snow Waiting for me out there in the dark. -Charles Simic NYRB Jan 13. 2011 Cần Gì Nữa Đâu Bạn

bè của những giờ nho nhỏ của đêm Không

có em, thì sẽ chỉ có cái bộ mặt xanh xao của anh   BOOK 23: ARTISTS AND MODELS BY ANAIS NIN February 18,

2008 Dear Mr.

Harper, Valentine's

Day was just a few days ago and we've had a long cold snap here in

Saskatchewan-two good reasons to send you something warming. Yours truly,

Yann Martel ANAIS NIN

(1903-1977) was born in Paris, raised in the United States and

identified

herself as a Catalan-Cuban-French author. Nin was a prolific novelist,

short

story writer and diarist, best known for her multi-volume Diary. She

was also

one of the greatest writers of female erotica, and is famous for her

affairs

with notable individuals including Henry Miller and Gore Vidal. Note: Ngày

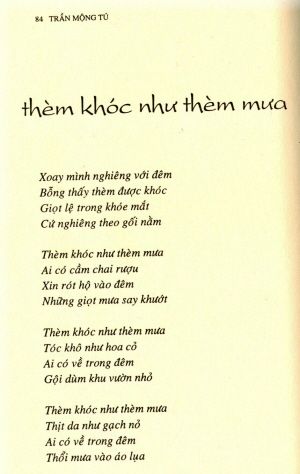

Tình Nhân, đề nghị đọc liền một mạch ba bài trên. “Thèm khóc

như thèm mưa/ Thịt da như gạch nỏ/Ai có về trong đêm/Thổi mưa vào áo

lụa” “Mưa không ướt

đất”! Bài thơ mới của Charles Simic,

xuất hiện trên tờ NYRB mà không tuyệt sao? Nhưng tuyệt nhất là lá thư gửi thủ trưởng Canada, nhân Ngày Tình Nhân của nhà văn Canada, Yann Martel. Khi chúng ta

trần truồng, chúng ta chân thật. *

Ed. Alfred

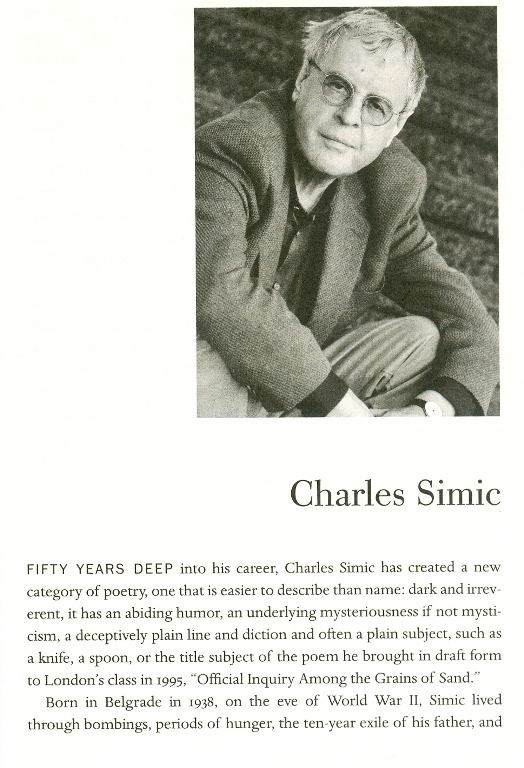

A. Knopf, NY, 2010 FIFTY YEARS

DEEP into his career, Charles Simic has created a new category of

poetry, one

that is easier to describe than name: dark and irreverent, it has an

abiding

humor, an underlying mysteriousness if not mysticism, a deceptively

plain line

and diction and often a plain subject, such as a knife, a spoon, or the

title

subject of the poem he brought in draft form to London's class in 1995,

"Official Inquiry Among the Grains of Sand." Born in

Belgrade in 1938, on the eve of World War II, Simic lived through

bombings,

periods of hunger, the ten-year exile of his father, and the

imprisonment of

his mother. "Hitler and Stalin conspired to make me homeless," he has

said. Not until he was in his mid-teens was his family reunited,

settling in

the United States. Simic began writing poetry as a high school student

in the

Chicago suburbs. One aim of

his poetry, Simic says, is "to restore strangeness to the most familiar

aspects of experience." To London he says that "the foundation of

poetry is based on chance," and as chance can run toward violence,

violence, too, is at an edge not far away. "Official Inquiry" and its

grains of sand run together with a snooping seagull of "a secret

government agency." But even as Simic describes line by line the making

of

the poem, he laughs when London suggests that he might have an overall

vision.

"No. No, I never had a vision," he says. "Sometimes awkwardness

is inevitable and important." Simic was

still making "Official Inquiry Among the Grains of Sand" at the time

of his visit. "Here's a little poem I'm working on," he wrote to her

weeks earlier. "This draft will change, so I'll have another version

when

I come." The poem eventually appeared in his 1996 volume, Walking

the Black Cat, a National Book

Award finalist and one of five books of poetry he published in the

1990S.

Simic, who has taught at the University of New Hampshire since 1973,

became the

U.S. poet laureate in 2007. Năm mươi năm

ăn nằm với thơ, Charles Simic đã tạo ra một thể loại thơ, mới, dễ miêu

tả hơn

là đặt tên cho nó: u tối, thiếu sự tôn kính, thường xuyên tưng tửng, bí

ẩn “chìm”,

nếu không muốn nói, thần bí; dòng thơ bằng phẳng đánh lừa người đọc;

lời phán,

và đề tài thường giản dị, như con dao, cái thìa, hay như tít bản nháp

bài thơ

mà ông mang vô lớp cho London coi, vào năm 1955: “Một cuộc điều tra

chính thức

giữa những hạt cát” Sinh tại

Belgrade 1938, đêm trước Đệ Nhị Chiến, Simic ‘đau đáu’ kinh qua bom

đạn, đói khát,

và 10 năm lưu vong của ông già và bà mẹ đi tù. “Hitler và Stalin, hai

thằng khốn

này đã âm mưu làm cho tôi thành 1 kẻ không có nhà ở”, ông đã từng nói.

Phải đến

khi ông được 15, 16 tuổi thì gia đình mới được đoàn tụ, và tái định cư

ở Mẽo.

Simic bắt đầu làm thơ khi học trung học ở vùng ngoại ô Chicago. Thơ tôi nhắm tái lập lại cái “kỳ kỳ cho hầu hết những sắc thái quen thuộc của kinh nghiệm”. “Cơ bản của thơ dựa trên cơ may, tình cờ”, và bởi vì cơ may thường chạy tới bạo động, thành thử bạo lực thì cũng ngay mép bờ, chẳng ở đâu xa. Và mặc dù ông làm thơ từng dòng, từng dòng, khi được hỏi, liệu ông có 1 viễn ảnh lớn, bao trùm lên nó, nhà thơ lắc đầu. Nô, tớ chẳng bao giờ có một viễn ảnh. “Đôi khi, cái sự lớ ngớ thì không thể tránh được, và nó thì quan trọng”

*

TALE A Prince was annoyed at always being occupied with perfecting vulgar generosities. He foresaw amazing revolutions in love, and suspected that his wives could come up with something better than complacency adorned with sky and luxury. He wished to see the truth, the hour of essential desire and satisfaction. Whether or not this was an aberration of piety, he wanted it. He possessed at the very least a rather broad human power. All the

women who had known him were murdered. What wanton pillaging of the

garden of

beauty! Beneath the saber, they gave him their blessing. He ordered no

new

ones.-The women reappeared. He killed

his followers, after the hunt or after drinking. -They all followed

him. He amused

himself with cutting the throats of thoroughbred animals. He torched

palaces.

He hurled himself on people and hacked them to pieces.-The crowds, the

golden

roofs, the beautiful beasts still lived. Is it

possible to become ecstatic amid destruction, rejuvenate oneself

through

cruelty! The people didn't complain. No one offered the support of his

own

opinions. One evening

he was galloping fiercely. A Genie appeared, of an ineffable, even

unfavorable

beauty. From his face and bearing sprang the promise of a multiple and

complex

love! of an unspeakable, even unbearable love! The Prince and the Genie

probably disappeared into essential health. How could they not die of

it? So

they died together. But this

Prince passed away, in his palace, at a normal age. The Prince was the

Genie.

The Genie was the Prince. Wise music

is missing from our desire. -From Arthur

Rimbaud's Illuminations (Translated

from the French by John Ashbery) Thèm khóc như

thèm mưa Thèm khóc như

thèm mưa Thèm khóc như

thèm mưa Ôi! Đêm nghiêng

theo gối Bốn khổ thơ chót, tuyệt. Hình ảnh "đêm

nghiêng theo gối", quái làm sao, làm Gấu nhớ tới Brodsky. Pages

full of women who are wet not because it's raining and men who are hard

not

because they're cruel. Em đã biết

tay anh chưa! "Thân cong như nhánh hoa"

thì Gấu hiểu, và tưởng tượng ra được, Thịt da như

gạch nỏ. Hình ảnh “đóm

nỏ hút thuốc lào”... đưa chúng ta

trở lại

với bài thơ của Akhmatova, như là 1 kết thức tuyệt vời cho những dòng

trên đây: THE LAST ROSE You will

write about us on a slant Bông Hồng Cuối Bạn sẽ viết,

nghiêng nghiêng, về chúng ta Tôi sẽ bay lên cùng khói từ giàn thiêu Dido Tôi sẽ khiêu vũ với Salome Và rồi lại bắt đầu với Joan trong giàn hỏa Ôi Chúa ơi! Người cũng biết đấy, ta mệt đến bã người Với ba chuyện làm xàm phục sinh, và chết, và sống, Lấy mẹ hết đi, cha nội, trừ CM – Hãy để cho ta cảm thấy sự mát rượi của món quà mà nàng mang tới!

|