|

Notes

|

Cuộc gặp gỡ

giữa Parvus và Lenin là cái nơ, cú khủng nhất trong cuốn sách của Solz.

Có

những nét cọ thật tuyệt ở đó, khi hai mảng băng hoại, hư ruỗng cuốn

quít với

nhau, vờn lẫn nhau: một là âm mưu toàn thế giới, và một là ước muốn bất

khả tri

về quyền lực. Còn có những giọng ngầm chói tai. Parvus là 1 tên Do Thái

lang

thang nhập thân, một kẻ “chuyên sửa chữa” thuộc bậc đại sư. Ông đầu tư

vào hỗn

mang, chao đảo, hoảng loạn, như đầu tư vào chứng khoán. Không có

Parvus, Solz

nhủ thầm, là Lenin hỏng cẳng, đếch làm sao thành công. Lenin với sức

mạnh, sự dẻo

dai Tartar, trở thành kẻ mang con “vai rớt” ngoại [chủ nghĩa CS quỉ

ma]. Trong

bản gốc, những ám dụ mang tính biểu tượng sắc tộc này, có người cho

rằng, thuổng Dos: cuộc đối đáp giữa Lenin-Parvus là từ những cuộc đối

đáp lớn về

siêu hình học về cái ác trong Anh em nhà

Karamazov của Dos. Sự thực, nếu coi Tháng Tám 1914 nằm trong mạch Tolstoy, diễn tả cái hoành tráng,

sử thi của Solz, thì Lenin ở Zurich là

1 tác phẩm thuộc dòng Dos, vẽ ra cả hai, chính trị học Slavophile, và

văn phong

bi tráng, “pamphleteering” [sách mỏng để

trình bầy

quan điểm, tư tưởng của 1 tác giả], của Dos. Thật hấp dẫn, táo tợn, và

riêng tư.

Tính

riêng tư ở trong A Voice from the

Chorus (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), Một tiếng nói từ bản đồng ca,

của

Abram Tertz thì lại thuộc một trật tự khác hẳn.

Tertz là bút hiệu của

Andrei

Sinyavsky, nổi tiếng khi cho xb tại Tây Phương, từ 1959 tới 1966, một

loạt bài

tiểu luận phê bình và những truyện ngắn thần kỳ, huyền hoặc, trộn lẫn

chủ nghĩa

hiện thực với chính trị a xít [làm cháy da cháy thịt đám tổ sư VC], và

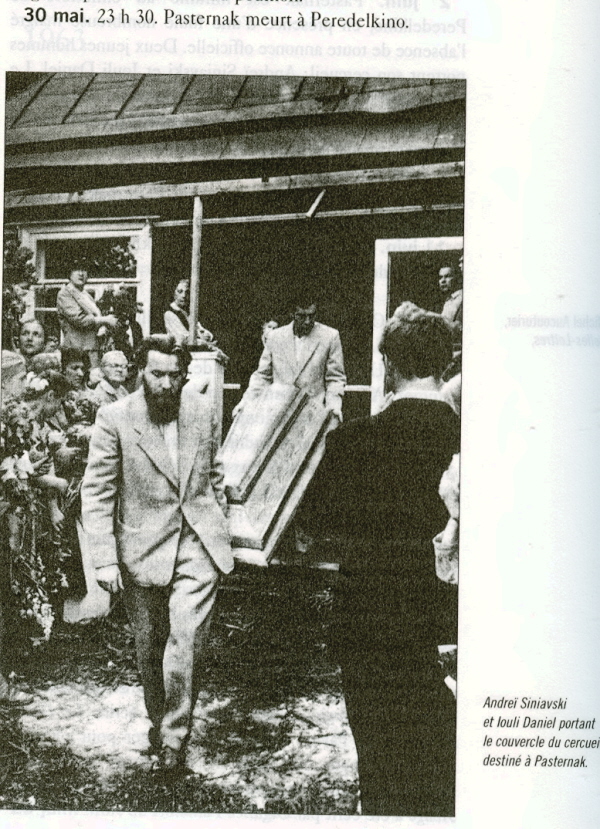

biếm văn xã hội. Ðây là do tác phẩm và sự mẫu mực của Pasternak mà cái

sự chôn

cất ông vào Tháng Năm 1960, mà Andrei Sinyavsky có dự phần, đã khiến

ông chọn

chống đối, và con đường nguy hiểm là cho in tác phẩm ở nước ngoài.

UNDER EASTERN EYES

Có một cái gì đó mang tính quốc

hồn quốc tuý, đặc Nga ở trong đó,

và nhất quyết không chịu bỏ nước ra đi.

Khi dịch câu trên, Gấu nghĩ đến Nguyễn Huy Thiệp, Văn Cao.

Nhất là NHT, và câu chuyện do anh kể, “tớ” đã từng đi vượt biên, nửa

đường bỏ

về, bị tay dẫn đường “xém” làm thịt!

Nhớ luôn cả cái tay phỏng vấn Gấu, và câu mở đầu cuộc phỏng vấn,

“off-record”,

lần Gầu trở lại đất Bắc sau hơn nửa thế kỷ xa cách:

Tôi cũng đi vượt biên, mấy lần, mà không thoát.

Nhưng, nhớ, nhất, là, Quê Người của Tô Hoài.

Dưới con mắt Đông phương

Có một nghịch

lý về thiên tài văn chương Nga. Từ Pushkin đến Pasternak, những sư phụ

của thơ

ca và giả tưởng Nga thuộc về thế giới, trọn một gói. Ngay cả ở trong

những bản

dịch què quặt của những vần thơ trữ tình, những cuốn tiểu thuyết và

những truyện

ngắn, chúng vẫn cho thấy một điều, không có chúng là không xong. Chúng

ta không

thể sẵn sàng bầy ra cái bảng mục lục những cảm nghĩ của chúng ta và của

nhân loại

nói chung, nếu không có chúng ở trong đó. Ngắn gọn, khiên cưỡng, theo

dòng lịch

sử, chỉ có văn học cổ Hy Lạp là có thể so đo kèn cựa được với văn học

Nga, nếu

nói về tính phổ quát. Tuy nhiên, với một độc giả không phải là người

Nga, khi đọc

Pushkin, Gogol, Dostoevsky, Mandelstam, họ vẫn luôn luôn là một kẻ đứng

bên lề,

một tên ngoại đạo. Họ có cảm giác mình đang nghe trộm, đọc lén một bản

văn, một

cuộc nói chuyện nội tại, rõ ràng thật dễ hiểu, sức truyền đạt cao, sự

thích hợp

phổ thông, vậy mà giới học giả, phê bình Tây phương, cho dù ở những tay

sắc sảo

nhất, vẫn không tin rằng họ hiểu đúng vấn đề. Có một cái gì đó mang

tính quốc hồn

quốc tuý, đặc Nga ở trong đó, và nhất quyết không chịu bỏ nước ra đi.

Tất

nhiên, đây là một vấn đề liên quan tới ngôn ngữ, hay chính xác hơn, đến

những

gam, những mảng quai quái, hoang dại của ngôn ngữ, từ tiếng địa phương,

của giới

quê mùa, cho tới thứ tiếng nói của giới văn học cao và Âu Châu hóa được

những

nhà văn Nga thi thố. Những trở ngại mà một Pushkin, một Gogol, một Anna

Akhmatova bầy ra, nhằm ngăn chặn một bản dịch tròn trịa, giống như một

con nhím

xù lông ra khi bị đe dọa. Nhưng điều này có thể xẩy ra đối với những

tác phẩm cổ

điển của rất nhiều ngôn ngữ, và, nói cho cùng, có một mức độ, tới đó,

những bản

văn lớn lao viết bằng tiếng Nga vượt qua (Hãy tưởng tượng "quang cảnh

quê

ta" sẽ ra sao nếu thiếu Cha và Con,

hay Chiến tranh và Hòa bình, hay Anh em

nhà Karamazov, hay Ba chị em). Và nếu có người vẫn

nghĩ rằng,

không đúng như vậy, rằng Tây phương, khi quá chú tâm vào một bản văn

thì đã làm

méo mó, sai lạc điều mà một nhà văn Nga tính nói, thì không thể chỉ là

do khoảng

cách về ngôn ngữ.

Văn học Nga

được viết dưới con mắt cú vọ của kiểm duyệt. Người Nga cũng là giống

dân đầu

tiên đưa ra nhận xét có tính “chuyện thường ngày ở huyện” này. Lấy đơn

vị là một

năm, thì, chỉ chừng một năm thôi [“là phai rồi thương nhớ”], mọi thứ

“sĩ” của

Nga, thi sĩ, tiểu thuyết gia, kịch tác gia, người nào người nấy, viết,

với con

mắt dòm chừng của nhân dân, thay vì với tự do suy tư. Một tuyệt tác của

Nga hiện

hữu “mặc dù” chế độ. Nói rõ hơn, dưới chế độ độc tài kiểm duyệt, nhìn

chỗ nào

cũng thấy có cặp mắt của…cớm, vậy mà Nga vưỡn có tuyệt phẩm!

Một tuyệt phẩm

như thế, nó chửi bố chế độ, nó mời gọi lật đổ, nó thách đố, hoặc trực

tiếp, hoặc

với một sự mặc cả hàm hồ nào đó, với chính quyền, hoặc Chuyên Chính Nhà

Thờ, hoặc

Mác Xít Lê Nin Nít, Xì Ta Lít.

Bởi vậy mà

Nga có 1 thật câu thật hách [thật oách, cho đúng tiếng Bắc Kít], nhà

văn nhớn

là một “nhà nước thay đổi, xen kẽ, đổi chiều”, “the alternative state”.

Những

cuốn sách của người đó, là một hành động chủ yếu - ở nhiều điểm, độc

nhất - của

sự chống đối chính trị.

Trong trò

chơi mèo chuột khó hiểu như thế đó, và nó gần như không thay đổi, kể từ

thế kỷ

18, Viện Cẩm Linh cho phép sáng tạo, và có khi còn cho phát hành, quảng

bá những

tác phẩm nghệ thuật hiển nhiên mang tính nổi loạn, phản động.

Với dòng đời

trôi qua, thế hệ này tiếp nối thế hệ khác, những tác phẩm như thế đó -

của

Pushkin, Turgenev, Chekhov - trở thành cổ điển, chúng là những cái van

an toàn

chuyển vào miền tưởng tượng một số những đòi hỏi thay đổi, đổi mới

chính trị,

mà thực tại không cho phép. Cuộc truy lùng, săn đuổi những nhà văn-từng

người,

tống vào tù, cấm đoán sách của họ, là 1 phần của sự mà cả giữa đôi bên.

Một kẻ ở bên

ngoài, không phải Nga, chỉ có thể biết đến cỡ đó. Anh ta nhìn vào nỗi

đau khổ của

Pushkin, sự chán chường của Gogol, hạn tù của Dostoevsky ở Siberia,

cuộc chiến

đấu thống khổ chống lại kiểm duyệt của Tolstoi, hay nhìn vào bảng mục

lục dài

những kẻ bị sát hại, mất tích, nó là cái biên nhận về sự thành tựu văn

học Nga

thế kỷ 20, và anh ta sẽ nắm bắt được “cơ chế”: Nhà văn Nga xục xạo,

dính líu

vào đủ thứ chuyện. Chỗ nào nhân dân Nga cần, là có nhà văn Nga. Anh ta

dí mũi vào

đủ thứ, khác hẳn thái độ buồn chán, và dễ dãi của đồng nghiệp Tây

phương. Thường

xuyên, trọn ý thức Nga được truyền vào ngòi viết của anh ta. Và để đổi

lại, là

mạng sống của anh ta, nói cách khác, anh ta trải đời mình, len lỏi đời

mình, suốt

địa ngục. Nhưng cái biện chứng tàn nhẫn này thực sự cũng không nói trọn

sự thực,

nó vẫn giấu đi ở trong chính nó, một sự thực khác, mà bằng trực giác,

nó thì thật

là hiển nhiên giữa những đấng nghệ sĩ Nga, nhưng kẻ bên ngoài đừng hòng

nắm bắt

được.

Lịch sử Nga

là một lịch sử của đau khổ và nhục nhã gần như không làm sao hiểu được,

hay, chấp

nhận được. Nhưng cả hai - quằn quại vì đau khổ, và ô nhục vì hèn hạ -

nuôi dưỡng

những cội rễ một viễn ảnh thiên sứ, một cảm quan về một cái gì độc nhất

vô nhị,

hay là sự phán quyết sáng ngời. Cảm quan này có thể chuyển dịch vào một

thành

ngữ “the Orthodox Slavophile”, với niềm tin của nó, là, Nga là một xứ

sở thiêng

liêng theo một nghĩa thật là cụ thể, chỉ có nó, không thể có 1 xứ nào

khác, sẽ

nhận được những bước chân đầu tiên của Chúa Ky Tô, khi Người trở lại

với trần

gian. Hay, nó cũng có thể được hoá thân vào trong chủ nghĩa thế tục

thiên sứ

[chúng ông đều là Phù Ðổng Thiên Vương cả đấy nhé, như anh VC Trần Bạch

Ðằng đã

từng thổi mấy đấng Bộ Ðội Cụ Hồ], với niềm tin, đòi hỏi sắt đá của CS

về một xã

hội tuyệt hảo, về một rạng đông thiên niên kỷ của một công lý tuyệt đối

cho con

người, và tất nhiên, tất cả đều bình đẳng, hết còn giai cấp. Một cảm

quan chọn

lựa thông qua khổ đau, vì khổ đau, là nét chung của cảm tính Nga, với

thiên

hình vạn trạng dạng thức của nó. Và điều đó còn có nghĩa, có một liên

hệ tam

giác giữa nhà văn Nga, độc giả của người đó, và sự hiện diện đâu đâu

cũng có của

nhà nước, cả ba quyện vào nhau, trong một sự đồng lõa quyết định. Lần

đầu tiên

tôi mơ hồ nhận ra mùi đồng lõa bộ ba này, lần viếng thăm Liên Xô, đâu

đó sau

khi Stalin chết. Những người mà tôi, hay một ai đó gặp, nói về cái sự

sống sót

của họ, với một sự ngỡ ngàng chết lặng, không một khách tham quan nào

thực sự

có thể chia sẻ, nhưng cũng cùng lúc đó, cùng trong giọng ngỡ ngàng câm

nín đó,

lại ló ra một hoài niệm, tiếc nuối rất ư là kỳ quái, rất ư là tế vi.

Dùng cái từ

“hoài niệm” này thì quả là quá lầm lẫn! Nhưng quả là như thế, tếu thế!

Họ không

quên những điều ghê rợn mà họ đã từng trải qua, nhưng họ lại xuýt xoa,

ui chao,

may quá, những điều ghê rợn đó, chúng tôi được Ðại Ác Nhân ban cho,

được một

Hùm Xám thứ thiệt ban cho, chứ không phải đồ gà chết! Và họ gợi ý rằng,

chỉ cái

sự kiện sống sót tại Nga dưới thời Xì Ta Lin, hay dưới thời Ivan Bạo

Chúa là một

bằng chứng hiển nhiên về nguy nga tận thế hay về lạ kỳ sáng tạo của số

mệnh, Cuộc

bàn luận giữa chính họ với sự ghê rợn thì mang tính nội tại, riêng tư,

cá nhân.

Người ngoài, nghe lén được thì chỉ biểu lộ sự rẻ rúng, hay đáp ứng bằng

1 thái độ

sẵn sàng, dễ dãi.

Những

đại văn hào Nga là như thế đó. Sự kêu gào

tự do của họ, sự rất ư bực mình của họ trước cái lương tâm ù lì của Tây

Phương,

thì rất ư là rền rĩ và rất ư là chân thực. Nhưng họ không chờ đợi được

lắng

nghe hay được đáp ứng bằng một thái độ thẳng thừng, ngay bong. Những

giải pháp thì

chỉ có thể có được, từ phía bên trong, theo kiểu nội ứng với những

chiều hướng

thuần sắc tộc và tiên tri. Nhà thơ Nga sẽ thù ghét tên kiểm duyệt,

khinh miệt lũ

chó săn, đám côn đồ cảnh sát truy nã anh ta. Nhưng anh ta sẽ chọn thế

đứng với

chúng, trong 1 liên hệ có tính cần thiết nhức nhối, cho dù đó là do

giận dữ,

hay là do thông cảm. Cái sự kiêu ngạo nguy hiểm, rằng có một mối giao

hảo theo

kiểu nam châm hút lẫn nhau giữa kẻ tra tấn và nạn nhân, một quan niệm

như thế

thì quá tổng quát, để mà xác định tính chất của bàu khí linh văn Nga.

Nhưng nó gần gụi hơn, so với sự ngây thơ

tự do. Và nó

giúp chúng ta giải thích, tại sao cái số mệnh tệ hại nhất giáng xuống

đầu một

nhà văn Nga, thì không phải là cầm tù, hay, ngay cả cái chết, nhưng mà

là lưu

vong qua Tây Phương, một chốn u u minh minh rất dễ tiêu trầm, may lắm

thì mới có

được sự sống sót.

Và

cuộc

lưu vong, phát vãng

xứ người, ra khỏi khối u, hộp đau, cục uất đó, bây giờ ám ảnh

Solzhnitsyn. Với

con người mãnh liệt bị ám ảnh này, có một cảm quan thực, qua đó, sự

nhập thân nơi

Gulag đem đến vinh quang và sự miễn nhiễm ở Tây Phương. Solz ghét Tây

Phương, và

cái sự la làng lên của ông về điều này thì chỉ khiến người ta dửng dưng

và… vô

tri. Cách đọc lịch sử của ông theo lý thuyết thần học Slavophile thì

cực rõ. Cuộc

cách mạng Pháp 1789 thăng hoa những ảo tưởng thế tục của con người,

cuộc nổi loạn

hời hợt của nó chống lại Chúa Ky Tô, và mạt thế luận. Chủ nghĩa Mác là

hậu quả

tất nhiên không thể nào tránh được, của cái thứ tự do bất khả tri này.

Và chính

con vai rớt, khuẩn trí thức, “đặc mũi lõ” đó, được đám trí thức mất

gốc, phần lớn

là Do Thái, cấy vô máu Gấu Mẹ vĩ đại, là nước Nga Thiêng, the Holy

Russia.

Gấu Mẹ vĩ đại sở dĩ nhiễm độc là do những rất dễ bị tổn

thương, và hỗn loạn của hoàn cảnh, điều kiện một nước Nga sau những

khủng

hoảng quân sự lớn

1914. Chủ nghĩa CS là một nhạo nhại của những lý tưởng thực sự về đau

khổ, tình

anh em đã làm cho nước Nga được Chúa chọn.

Nhưng 1914 chứng

kiến một nước Nga nhếch nhác,

thảm

hại tàn

khốc, và vô phương chống lại cơn dịch của chủ nghĩa

duy lý vô

thần.

Từ

đó, chúng ta nhận ra tầm quan trọng khủng mà Solz đánh vào năm đầu của

cuộc Thế

Chiến, và sự giải quyết của ông, để làm bùng nổ ra mọi khía cạnh vật

chất và

tinh thần của 1914 [một mùa Thu năm qua cách mạng tiến ra], và của

những sự kiện

đưa tới [Tôi nói đồng bào nghe rõ không] Tháng Ba, 1917, trong một dẫy

những “sự

kiện- giả tưởng” khổng lồ.

Nhưng

trong cái khoa nghiên cứu quỉ ma này, Lenin đặt ra 1 vấn đề mà Solz

cũng đã từ

lâu quan tâm tới. Chủ nghĩa Mác có thể là thứ bịnh [quỉ] của Tây Phương

và Hê-brơ

[Do Thái], nhưng Lenin là một Trùm Nga, và chiến thắng Bôn sê vích chủ

yếu là của

ông ta. Rõ ràng, trong những bản viết đầu tay của Solz đã có những dấu

vết chứng

tỏ, một cá nhân con người, như là tác giả những bài viết, chống lại 1

hình tượng

như là Lenin.

Trong

một nghĩa chỉ có tí phần có tính ám dụ, Solz hình như cảm ra được rằng,

ý chí, ước

muốn kỳ quặc

và viễn ảnh của riêng ông có gì xêm xêm của Lenin, và, cuộc chiến

đấu cho linh

hồn và tương lai của nước Nga, sẽ là cuộc tử đấu giữa ông và người tạo

ra hệ thống

Xô Viết: Trời cho mi ra đời là để dựng nên Xô Viết, còn ta, để huỷ diệt

nó. Và

tiếu lâm thay, đúng như 1 cú của định mệnh, thiên đường không đi, mà cả

hai cùng

hẹn nhau, không cùng lúc mà là trước sau, lần lượt: Solz thấy mình ở

Zurich, cũng

trong tình trạng lưu vong, với Lenin, là trước cú tận thế

1914. Solz

đã

đi 1 chương về Lenin trong “Tháng Tám 1914”, và còn dư chất

liệu cho những tập kế tiếp mà ông đặt tên

là “Knots". Nhưng cú tính cờ Zurich thì quá giầu có để mà bỏ đi. Từ đó,

xuất

hiện Lenin ở Zurich (nhà xb Farrar,

Strauss & Giroux).

Kết quả

thì

không tiểu thuyết mà cũng chẳng luận văn chính trị, mà chỉ là một bộ,

set, những

điểm xuyết nặng ký, in depth. Solz nhắm “lên sơ đồ, hoạch định, tìm ra”

những sở

đoản, điểm bại, tử huyệt của Lenin. Tin tức về Cách Mạng Nga đến với

Lenin

trong kinh hoàng, theo nghĩa, ông hoàn toàn ngạc nhiên đến sững sờ. Ðầu

óc thiên

tài quỉ quyệt với những âm mưu gây loạn của Lenin khi đó chỉ nhắm tạo

bất ổn ở

Thuỵ Sĩ và đẩy đất nước này vào 1 cuộc chiến.

Ngồi ăn sáng mà Lenin buỗn

nẫu ruột. Người

quậy tứ lung tung cố moi ra tiền vỗ lớn cái bào thai cách mạng. Người

nhức đầu

vì một người đàn bà khác trong cuộc đời khổ hạnh của Người, nàng Inessa Armand cực phấn kích, làm rùng mình, và

chấp nhận “lệch

pha ý hệ” ra khỏi nàng, và điều này có nghĩa là một đệ tử của

Thầy bị ăn

đòn!

Trên hết, như Solz, đích thị xừ luỷ,

Người nhận

thấy cái sự khoan thứ, rộng luợng đã được khử trùng và trở thành

trong

suốt của chủ nhà Thụy Sĩ khiến Người trở

nên khùng:

Cả Zurich,

chừng ¼ triệu

con người, dân địa phương , hay từ các phần khác của Âu Châu, xúm xít ở

dưới đó,

làm việc, trao đổi công chuyện, đổi tiền, bán, mua, ăn nhà hàng, hội

họp, đi bộ,

lái xe lòng vòng, mỗi người mỗi ngả, mỗi cái đầu thì đầy những ý nghĩ, tư tưởng chẳng

có trật tự, chẳng hướng về đâu. Trong khi đó, đứng trên đỉnh núi, Người

biết

cách hướng dẫn họ, và thống nhất thành một mối ước muốn của họ.

Ngoại trừ

điều này: Người đếch có tí quyền lực cần

thiết. Người có

thể đứng trên đỉnh Zurich, hay nằm trong mồ, nhưng không thể thay đổi

Zurich. Người

đã sống hơn một năm ở đó, mà mọi cố gắng của Người đều vô ích, chẳng có

gì thay

đổi.

Và, kìa,

chúng lại sắp hội

hè nữa kìa!

Lenin trở về

Nga, trong

cái “xe đóng khằn” trứ danh, với sự đồng lõa của nhà cầm quyền hoàng gia Ðức,

và bộ tướng lãnh (họ mong làm sao chiến tranh đừng xẩy ra tại Nga).

Nhưng Lenin

chẳng hề có tham vọng này. Nó là từ cái đầu của Parvus, alias Dr.

Helphand, alias Alexander Israel Lazarevich. Mặc dù cả một

cuốn tiểu sử hoành tráng của Z.A. Zeman và W.E. Scharlau, “Tên mại bản

cách

mạng”, "The Merchant of Revolution", chúng ta chẳng biết chi nhiều,

và rõ ràng, về ông này. Một nhà cách mạng a ma tưa, nhưng tầm nhìn đôi

khi vượt

cả của Lenin. Một tay gây vốn thiên tài cho Bolsheviks, nhưng còn là

gián điệp

nhị trùng, tam thùng, đi đi lại lại giữa các phần tử, đảng phái Thổ Nhĩ

Kỳ, Ðức,

và Nga. Ăn diện bảnh bao, dandy, người của muôn phương, cosmopolite,

chàng bèn

liền lập tức bị mất hồn và sướng điên lên vì chủ nghĩa khổ hạnh đến cuồng tín của

những đường hướng của Lenin. Tòa villa sang trọng, giầu sang mà Parvus xây

cho chính ông ta ở Berlin, và vào năm 1942, chết ở đó, sau

này được Himmler sử dụng để đi một đường “giải pháp chót” [nhổ sạch cỏ]

cho giống

dân Do Thái.

Bài

điểm cuốn sách mới nhất

về Solz, trên tờ Điểm Sách London, 11 Sept, 2008

Nhiệm

vụ của Solz: Solz's Mission.

Nhiệm vụ gì?

Chàng ra đời, với số mệnh làm

thịt Xô Viết, cũng như Lenin, ra đời, để xây dựng nó!

Like any prophet - like

Lenin... he knew himself born to a historic destiny... In the end, his

mission,

like Lenin, succeeded. In fact, one might say that it succeeded at

Lenin's

expense, a triumphant negation of Lenin's success.

Cuốn sách khổng lồ, về tiểu

sử Solz: gần 1 ngàn trang, với những tài liệu mới tinh, từ hồ sơ KGB.

Một David vs Soviet Goliath

What a fighter!

Chàng dũng sĩ tí hon chiến

đấu chống anh khổng lồ Goliath Liên Xô mới khủng khiếp làm sao. Niềm

tin của

chàng mới ghê gớm thế nào: Tao lúc nào cũng đúng!

Chính trại tù đã làm nên

Solz. Nhờ lao động cải tạo mà ông được cứu vớt, mất đi niềm tin Mác xít

Lêninít,

và tìm lại được niềm tin Chính thống giáo khi còn nhỏ, và nhận ra lời

gọi [the

calling]: ta sẽ là một ký sự gia của trại tù và kẻ tố cáo hệ thống Xô

viết [the

camps’ chronicler and the Xoviet system’s denouncer]

Đây có lẽ là cuốn tiểu sử mới

nhất, đầy đủ nhất [sửa chữa những sai sót trước đó về Solz]. Và tuyệt

vời nhất.

Tin Văn sẽ scan bài điểm hầu quí vị!

*

Nhìn ra số mệnh của Solz như

thế, và gắn nó với số mệnh của Lenin như vậy, thì thật là tuyệt. Mi

sinh ra là để hoàn thành Xô Viết, còn ta sinh ra để huỷ diệt nó, và tố

cáo với toàn thế giới cái sự ghê tởm, cái ác cực ác của nó.

G. Steiner

Bài viết này thật là thần

sầu.

Một cách nào đó, Gấu bị lừa, vì

một “thiên sứ” dởm, bởi vậy, khi

Chợ Cá vừa xuất hiện là Anh Cu Gấu bèn cắp rổ theo hầu SCN liền tù tì.

Gấu đọc NHT

là cũng theo dòng “chuyện tình không

suy tư” như vậy: “chấp nhận” Tướng Về Hưu, "thông cảm" với ông ta,

sau khi góp phần xây dựng xong xuôi Ðịa Ngục Ðỏ của xứ Mít, bèn về hưu,

sống

nhờ đàn heo, đuợc vỗ béo bằng những thai nhi của cô con dâu Bắc Kít...

THERE IS A

contradiction about the genius of Russian literature. From Pushkin to

Pasternak, the masters of Russian poetry and fiction belong to the

world as a

whole. Even in lame translations, their lyrics, novels, and short

stories are

indispensable. We cannot readily suppose the repertoire of our feelings

and

common humanity without them. Historically brief and constrained as it

is in

genre, Russian literature shares this compelling universality with that

of

ancient Greece. Yet the non-Russian reader of Pushkin, of Gogol, of

Dostoevsky,

or of Mandelstam is always an outsider. He is, in some fundamental

sense,

eavesdropping on an internal discourse that, however obvious its

communicative

strength and universal pertinence, even the acutest of Western scholars

and

critics do not get right. The meaning remains obstinately national and

resistant to export. Of course, this is in part a matter of language

or, more

accurately, of the bewildering gamut of languages ranging all the way

from the

regional and demotic to the highly literary and even Europeanized in

which

Russian writers perform. The obstacles that a Pushkin, a Gogol, an

Akhmatova

set in the way of full translation are bristling. But this can be said

of

classics in many other tongues, and there is, after all, a

level-indeed, an

immensely broad and transforming level-on which the great Russian texts

do get through.

(Imagine our landscape without Fathers

and Sons or War and Peace or The

Brothers Karamazov or The Three Sisters.) If one

still feels

that one is often getting it wrong, that the Western focus seriously

distorts

what the Russian writer is saying, the reason cannot only be one of

linguistic

distance.

It is a

routine observation-the Russians are the first to offer it-that all of

Russian

literature (with the obvious exception of liturgical texts) is

essentially

political. It is produced and published, so far as it can be, in the

teeth of

ubiquitous censorship. One can scarcely count a year in which Russian

poets,

novelists, or dramatists have worked in anything approaching normal,

let alone

positive, conditions of intellectual freedom. A Russian masterpiece

exists in

spite of the regime. It enacts a subversion, an ironic circumlocution,

a direct

challenge to or ambiguous compromise with the prevailing apparatus of

oppression, be it czarist and Orthodox ecclesiastical or

Leninist-Stalinist. As

the Russian phrase has it, the great writer is "the alternative

state." His books are the principal, at many points the only, act of

political opposition. In an intricate cat-and-mouse game that has

remained

virtually unchanged since the eighteenth century, the Kremlin allows

the

creation, and even the diffusion, of literary works whose fundamentally

rebellious character it clearly realizes. With the passage of

generations, such

works- Pushkin's, Turgenev's, Chekhov's-become national classics: they

are

safety valves releasing into the domain of the imaginary some of those

enormous

pressures for reform, for responsible political change, which reality

will not

allow. The hounding of individual writers, their incarceration, their

banishment, is part of the bargain.

This much

the outsider can make out. He looks at the harrowing of Pushkin, at

Gogol's

despair, at Dostoevsky's term in Siberia, at Tolstoy's volcanic

struggle

against censorship, or at the long catalogue of the murdered and

missing which

makes up the record of twentieth-century Russian literary achievement,

and he

will grasp the underlying mechanism. The Russian writer matters

enormously. He

matters far more than his counterpart in the bored and tolerant West.

Often the

whole of Russian consciousness seems to turn on his poem. In exchange,

he

threads his way through a cunning hell. But this grim dialectic is not

the

whole truth, or rather it conceals inside itself another truth

instinctively

apparent to the Russian artist and his public but almost impossible to

gauge

rightly from outside.

Russian

history has been one of nearly inconceivable suffering and humiliation.

But both

the torment and the abjection nourish the roots of a messianic vision,

of a

sense of uniqueness or radiant doom. This sense can translate into the

idiom of

the Orthodox Slavophile, with his conviction that the Russian land is

holy in

an absolutely concrete way, that it alone will bear the footsteps of

Christ's

return. Or it can be metamorphosed into the messianic secularism of the

Communist claim to a perfect society, to the millenary dawn of absolute

human

justice and equality. A sense of election through and for pain is

common to the

most varied shade~ of Russian sensibility. And it means that there is

to the

triangular relationship of the Russian writer, his readers, and the

omnipresent

state that enfolds them a decisive complicity. I had my first inkling

of this

when visiting the Soviet Union some time after Stalin's death. Those

whom one

met spoke of their survival with a numbed wonder that no visitor could

really

share. But at the very same moment there was in their reflections on

Stalin a

queer, subtle nostalgia. This is almost certainly the wrong word. They

did not

miss the lunatic horrors they had experienced. But they implied that

these

horrors had, at least, been dished out by a tiger, not by the paltry

cats now

ruling over them. And they hinted that the mere fact of Russia's

survival under

a Stalin, as under an Ivan the Terrible, evidenced some apocalyptic

magnificence or creative strangeness of destiny. The debate between

themselves

and terror was an internal, private one. An outsider demeaned the

issues by

overhearing it and responding to it too readily.

So it is

with the great Russian writers. Their cries for liberation, their

appeals to

the drowsy conscience of the West are strident and genuine. But they

are not

always meant to be heard or answered in any straightforward guise.

Solutions

can come only from within, from an inwardness with singular ethnic and

visionary

dimensions. The Russian poet will hate his censor, he will despise the

informers and police hooligans who hound his existence. But he stands

toward

them in a relationship of anguished necessity, be it that of rage or of

compassion. The dangerous conceit that there is a magnetic bond between

tormentor and victim is too gross to characterize the Russian

spiritual-literary ambience. But it gets nearer than liberal innocence.

And it

helps explain why the worst fate that can befall a Russian writer is

not

detention or even death but exile in the Western limbo of mere

survival.

It is just

this exile, this ostracism from the compact of pain which now obsesses

Solzhenitsyn. For this haunted powerful man, there is a real sense in

which

reincarceration in the Gulag would be preferable to glory and immunity

in the

West. Solzhenitsyn detests the West, and the oracular nonsense he has

uttered

about it points as much to indifference as to ignorance. Solzhenitsyn's

theocratic-Slavophile

reading of history is perfectly clear. The French Revolution of 1789

crystallized man's secular illusions, his shallow rebellion against

Christ and

a messianic eschatology. Marxism is the inevitable consequence of

agnostic

liberalism. It is a characteristically Western bacillus that was

introduced by

rootless intellectuals, largely Jews, into the bloodstream of Holy

Russia. The

infection took because of the terrible vulnerabilities and confusions

of the

Russian condition after the first great military disasters of 1914.

Communism

is a travesty of the true ideals of suffering and brotherhood that made

Russia

the elect of Christ. But 1914 saw Mother Russia fatally disheveled and

defenseless against the plague of atheist rationalism. Hence the

tremendous

importance that Solzhenitsyn attaches to the first year of the World

War, and

his resolve to explore every material and spiritual aspect of 1914 and

of the

events leading up to March, 1917, in a row of voluminous

"fact-fictions."

But in this

demonology Lenin poses a problem, of which Solzhenitsyn has long been

aware.

Marxism may have been a Western and Hebraic disease, but Lenin is an

arch-Russian figure and the Bolshevik victory was essentially his

doing.

Already in Solzhenitsyn’s earlier writings there were traces of a

certain

antagonistic identification of the author with the figure of Lenin. In

a sense

that is only partly allegorical, Solzhenitsyn seems to have felt that

his own

uncanny force of will and vision were of a kind with Lenin's and that

the

struggle for the soul and future of Russia lay between him and the

begetter of

the Soviet regime. Then, by a turn of fate at once ironic and

symbolically

inescapable, Solzhenitsyn found himself in Zurich, in the same prim,

scrubbed,

chocolate-box arcadia of exile in which Lenin raged away his time

before the

1917 apocalypse. He had left out a Lenin chapter in "August 1914" and

had much Lenin material in hand for later volumes-or "Knots," as he

now calls them. But the Zurich coincidence was too rich to be left

fallow. From

it comes the interim scenario Lenin in

Zurich (Farrar, Straus & Giroux).

The result

is neither a novel nor a political tract but a set of vignettes in

depth.

Solzhenitsyn aims to establish Lenin's fallibility. News of the Russian

Revolution takes the Bolshevik leader totally by surprise. What he has

been

concentrating his conspiratorial genius on is a wildly involutes and

harebrained scheme to involve Switzerland in the war and consequent

social

unrest. Lenin worries over his breakfast. He dabbles fastidiously in

each and

any contrivance that may secure funds for his embryonic movement. He

aches for

the other woman in his austere life, the thrilling Inessa Armand, and

accepts

ideological deviations from her that would bring down anathema on any

other

disciple. Above all, like Solzhenitsyn himself, he finds the antiseptic

tolerance of his Swiss hosts maddening:

All Zurich,

probably a quarter of a million people, locals or from other parts of

Europe,

thronged there below, working, making deals, changing currency,

selling,

buying, eating in restaurants, attending meetings, walking or riding

through

the streets, all going their separate ways, every head full of thoughts

without

discipline or direction. And he stood there on the mountain knowing how

well he

could direct them all, and unite their wills.

Except that

he lacked the necessary power. He could stand here up above Zurich, or

lie in

that grave, but he could not change Zurich. He had been living here for

more

than a year, and all his efforts had been in vain, nothing had been

done.

And, to make

matters worse, the good burghers are about to stage another one of

their

tomfool carnivals.

Lenin will

get back to Russia in the famous "sealed carriage," with the

connivance of the German imperial government and general staff (anxious

to get

Russia out of the war). But this brilliantly ambiguous escapade is not

the

product of Lenin's cunning or political means. It springs from the

teeming

brain of Parvus, alias Dr. Helphand, alias Alexander Israel Lazarevich.

Despite

a full-scale biography by Z.A. Zeman and W.E. Scharlau, "The Merchant

of

Revolution," much about Parvus remains unclear. He was an amateur

revolutionary whose foresight sometimes exceeded Lenin's own. He was a

fundraiser of genius for the Bolsheviks, but also a double or triple

agent

acting as go-between for Turkish, German, and Russian parties. He was a

dandy

and cosmopolite, at once fascinated and amused by the fanatic

asceticism of

Lenin's ways. The opulent villa that Parvus built for himself in

Berlin, and in

which he died, in 1924, was later used by Himmler to plan "the final

solution."

The meeting

between Parvus and Lenin is the crux of Solzhenitsyn’s book. There are

fine

touches in it, as two kinds of corruption, that of worldly intrigue and

that of

an agnostic will to power, circle each other. There are also grating

undertones. Parvus is the wandering Jew incarnate, the supreme fixer.

He

invests in chaos as he does on the bourse. Without Parvus, Solzhenitsyn

intimates, Lenin might not have succeeded. Lenin, with his own Tatar

strength,

becomes the carrier of a foreign virus. In the original, these

ethnic-symbolic

allusions are, one suspects, underlined by the analogies between the

Lenin-Parvus dialogue and the great dialogues on the metaphysics of

evil in

Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov.

Indeed, if "August

1914" can he said to illustrate, not altogether coherently,

Solzhenitsyn's

Tolstoyan side, his epic vein, Lenin in Zurich is a frankly

Dostoevskian work,

drawing both on Dostoevsky’s Slavophile politics and on his dramatic

pamphleteering

style. It is intriguing but scrappy and, in many respects, very

private.

The privacy

of Abram Tertz's A Voice from the Chorus

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux) is of an entirely different order. Tertz

is the

pen name of Andrei Sinyavsky, who became famous with the publication in

the

West, from 1959 to 1966, of a series of critical essays and fantastic

tales,

blending surrealism with acid political and social satire. It was the

work and

example of Pasternak, at whose burial in May, 1960, he took a prominent

part,

that seem to have compelled Sinyavsky toward opposition and the

dangerous road

of publication abroad. He had begun, like so many of his generation, as

a Communist

idealist or even Utopian. Doctor Zhivago,

the revelations concerning the true nature of Stalinism in Khrushchev's

Twentieth

Party Congress speech, and his own sharp-eyed observations of Soviet

reality

disillusioned Sinyavsky. By means of critical argument and poetic

invention, he

sought an alternative meaning of Russian existence.

For a time,

"Abram Tertz"-the name is that of the hero of an underworld ballad

from the Jewish thieves' quarter of Odessa - protected Andrei

Sinyavsky. But

the secret leaked out, and Sinyavsky, together with his fellow

dissident writer

Yuli Daniel, was arrested in September, 1965. The trial, in February,

1966, was

at once farcical and of extreme importance. The crime of the accused

lay in

their writings. This fact, added to the ferocity of the sentences

imposed, unleashed

a storm of international protest. More significantly, it gave impetus

to the

widespread intellectual dissent and clandestine distribution of

forbidden texts

(samizdat) which are now so vital a part of the Soviet scene.

From 1966 to

1971, Sinyavsky served his term in a succession of forced-labor camps.

Twice a

month, he was allowed to write a letter to his wife. Oddly, these

letters could

run to any length (the inmate having to use all the cunning and good

will

available to him in order to get paper). References to political topics

or the

literal horrors of camp life would be instantly punished. But within

these

limits the prisoner could let his mind and pen roam free. "A Voice from

the Chorus" is based on Sinyavsky's missives from the house of the

dead.

But this is

no prison journal. There are few dates or circumstantial details. What

Sinyavsky has kept for us is a garland of personal meditations on art,

on

literature, on the meaning of sex, and, principally, on theology.

Sinyavsky's

literary range is prodigious: he sets down his reflections on many of

the major

figures in Russian literature, but also on Defoe, whose Robinson Crusoe

assumes

a direct, evident relevance to his own estate, and on Swift. His inner

eye of

loving remembrance passes over Rembrandt's "Prodigal Son" and the

holy icons, whose magic reflection of suffering becomes clearer and

clearer to

him. Though the actual details of the play are no longer certain in his

mind,

Sinyavsky writes a miniature essay on what he now takes to be the core

of

Hamlet-what he calls "the inner music of his image." Over and over,

he ponders the creative, fictive genius of human speech, its power to

shape

worlds.

In the

camps, Sinyavsky meets members of various religious sects dogged nearly

to

annihilation by Soviet repression. They range from strict Orthodoxy to

Christian fundamentalism (he records prisoners speaking in tongues) and

the

Islamic Faith as practiced among the chechen people of the Crimea.

These

encounters and his own sensibility impel Sinyavsky toward an

ever-deepening

religiosity. He studies Church Slavonic and the martyrs' chronicles; he

meditates on the unique place Orthodoxy assigns to the Assumption of

the Mother

of the Lord; he seeks to make out the possible relations between the

Russian

national character and the special focus of Orthodox theology on the

Holy

Ghost. Above all else, Sinyavsky bears witness that

The text of

the Gospels explodes with meaning. It radiates significance, and if we

fail to

see something, this is not because it is obscure, but because there is

so much,

and because the meaning is too bright-it blinds us. You can turn to it

all

through your life. Its light never fails. Like the sun's. Its

brilliance

astounded the Gentiles and they believed.

It was

doubtless this ecstatic piety, and its specifically Russian Orthodox

flavor of

accepted suffering, which enabled Sinyavsky to endure his sentence with

something akin to zest. He comes to cherish the slow tempo of camp

life: in it

"existence opens its blue eyes all the wider." Such is the radiance

of spiritual revelation that "when all is said and done, a camp gives

the

feeling of maximum freedom." where else do the woods, seen beyond the

barbed wire, glow with such Pentecostal flame or the stars throw down

their

spears before His coming?

Punctuating

these homilies are the literal "voices from the chorus"-brief

interjections, snatches of song, oaths, anecdotes, malapropisms

selected from

the babble of camp speech. Max Hayward, who with Kyril Fitzlyon has

produced

what is obviously a brilliant translation, tells us that these

fragments are

among the most fascinating to come out of modern Russia. He adds that

their

quality is accessible only to a Russian ear. This is certainly the

impression

one gets. There are haunting exceptions ("Buy yourself a nice pair of

shoes-and you'll feel just like King Lear" or "Till our children's

dying day!"), but most of the phrases are poignantly banal.

This is a

profoundly moving testimonial by a man of exceptional strength,

subtlety,

compassion, and faith. Deliberately, perhaps, it leaves a rather

dreamlike,

muted impression. Sinyavsky read a great deal in the camps. In fact, he

wrote a

dazzling study of Pushkin while incarcerated. How was this made

possible? Did

his reading include the prohibited texts of Pasternak, Akhmatova, and

Mandelstam to which he makes extended reference? One jotting alludes to

what

must have been an ideological discussion between a camp commander and

the

condemned. Was this an exceptional lapse of the usual discipline? One

of the

voices from the chorus makes a highly significant remark: "There used

to

be more fun in the camp in the old days. Someone was always being

beaten up or

hanged. Every day there was a special event." What are the

metamorphoses

in the politics of hell? There is so much more one would want to learn

about

from a witness of Sinyavsky's stature. But, again, his message is

intended for

Russian consumption. We eavesdrop. And Sinyavsky's exile-he now lives

in

Paris-makes this process the more uncomfortable.

Lydia

Chukovskaya's novel Going Under

(Quadrangle) is far more accessible to the Western reader than either

Solzhenitsyn's polemic fragment or Sinyavsky's memoir. The paradox is

that Miss

Chukovskaya is still "inside," in the twilight zone assigned to

writers, artists, and thinkers who have offended the regime and are

barred from

normal professional life. In the Soviet Union, Chukovskaya's writings

circulate, where at all, by clandestine mimeographs. Thus there is a

sense in

which Going Under-pellucidly

translated by Peter Weston-is meant for the outside. It is we who are

to

extract the message from the bottle.

The time is

February, 1949, and the zhdanovshchina-the

purge of intellectuals by Stalin's culture hoodlum, Andrei Zhdanov-is

beginning. The action takes place at a rest home for writers in Russian

Finland. Nina Sergeyevna, a translator, is one of the fortunate few to

whom the

Writers' Union has granted a month of pastoral repose away from the

stress of

Moscow. Ostensibly, she is to rest or get on with her translations.

What she is

actually attempting to do is to set down an account of her husband's

disappearance during the Stalin manhunts of 1938, and thus free

herself, at

least in part, from a long nightmare. Nothing very much happens at

Litvinovka.

Nina becomes more or less involved in the lives of Bilibin, a writer

who is

attempting to come to terms with the demands of his Stalinist masters

after a

spell at forced labor, and of Veksler, a Jewish poet and war hero. In

the

drawing room, the literati come and go, spitting venom on Pasternak,

their

nostrils quivering at the latest rumor of repression in Moscow. The

snow glows

among the birches, and just beyond the neat confines of the rest home

lie the

inhuman deprivation and backwardness of rural Russia in the aftermath

of total

war. Nina's bad dreams draw her back to the infamous queues of the

nineteen-thirties, tens of thousands of women waiting in vain in front

of police

stations for some word of their vanished husbands, sons, brothers.

(There are

echoes here of Akhmatova's great poem "Requiem.") Bilibin would make

love to her, out of the gentleness of his desolation. The N.K.V.D. come

for

Veksler. War heroes-Jewish war heroes in particular-are no longer

wanted. Soon

it is March and time to return to Moscow.

Set in a

minor key, this short novel echoes and re-echoes in one's mind. Every

incident

is at once perfectly natural and charged with implication. Walking in

the white

woods, Nina realizes that the Germans have been there, that the snow

masks a

literal charnel house. To have fought the Nazis in order to save and

consolidate Stalinism-the ironies are insoluble. When the suave hack

Klokov

denounces the obscurity of Pasternak, Nina's spirit writhes. But in her

solitude she is shadowed by the conviction that very great art can

belong only

to the few, that there is, sometimes in the greatest poetry, an

exaction that

cuts one off from the common pace and needs of humanity. The narrative

is both

spare and resonant. Pushkin, Akhmatova, Mandelstam, Pasternak, and

Turgenev are

obliquely present-especially Turgenev, whose play A Month

in the Country seems to counterpoint Chukovskaya's scenes.

This is a classic.

Under

Eastern eyes-Solzhenitsyn makes the point relentlessly-much of our own

concerns

and literature have a trivial mien. Seen from the Gulag, our urban

disarray or

racial tensions or economic hiccups look Edenic. The dimensions of

cruelty and

of endurance in which the Russian imagination works are, to most of us,

almost

unimaginable. So, even more strikingly, are the mechanisms of hope, of

exquisite moral perception, of vital enchantment that produce such

books as the

memoirs of Nadezhda Mandelstam or the tales of Chukovskaya. We don't

really

understand the daily breath of terror, and we don't understand the joy.

This is

because the indissoluble bond between them is for us, at best, a

philosophical

abstraction. "Driven into a cage," writes Sinyavsky, "the mind

is forced to break out into the wider open spaces of the universe

through the

back door. But for this to happen it must first be hunted down and

brought to

bay." The "cage" happens to be the name for the barred

compartment of Russian railway coaches in which prisoners travel to the

camps.

Within it, the Solzhenitsyn’s, the Sinyavskys, the Chukovskayas seem to

find

their freedom, as did Pushkin, Dostoevsky, and Mandelstam before them.

They

would not, one suspects, wish to trade with us. Nor is it for us to

imagine

that we can penetrate, let alone break open, the prison of their days.

October 11,

1976

GEORGE

STEINER: At The New Yorker

|

|