|

Notes

|

Tại sao chúng ta nên hủy bỏ

giải Nobel Văn học?

Thông thường, Viện Hàn lâm đề

cao những nhà văn cánh tả như Sinclair Lewis, Gunter Grass, Jose

Saramago,

Pablo Neruda hoặc Jean-Paul Sartre. Những nhà văn Mỹ từng giành giật

được giải

thưởng này là một nhóm khá pha tạp như: tác giả chống tư bản John

Steinbeck,

nhà văn hạng xoàng Pearl S. Buck.

Note: Đề cao những nhà văn cánh

tả, vậy mà đề nghị nên huỷ bỏ ư?

Bài viết của báo Mẽo, quê,

vì bị coi là biệt lập thiển cận, vậy mà Mít "tả hơn cả tả lớ", cũng hò

theo. Tiếu lâm

thật!

Mấy anh Mẽo kỳ thị đòi huỷ

Nobel, thì cũng đúng thôi, khi bị ông thư ký chọc đúng ngay tim, văn

chương Mẽo

biệt lập, và thiển cận. Như nhà văn Ha Jin, trong bài tựa cho cuốn Nhà văn như một di dân của ông, đây là

thứ văn chương di dân [nghĩa là biệt lập, thiển cận], với vấn đề di dân

của nó,

nhưng nhược điểm đấy, mà cũng là cơ may đấy.

V/v Mít ra ý kiến nên huỷ

giải

Nobel, Gấu này thấy quái quá.

Bởi vì chưa bao giờ giải Nobel lại bảnh

như mấy

năm vừa rồi. Có một cái gì lầm lẫn, trong lịch sử ban phát giải thưởng,

trong

suốt chiều dài của giải, và chỉ mới đây thôi, Viện Hàn Lâm Thuỵ Điển

mới nhìn

ra, và sửa sai.

Cái sự sửa sai này, theo Gấu, liên quan tới Cái Đại Á

của thế kỷ,

là Lò Thiêu của Nazi và Trại Tù của Stalin, và cùng với nó, là câu phán

hiển hách

của Benjamin: Mọi tài liệu về văn minh là một tài liệu về dã man.

Tập tiểu luận,

nhà xb University

of Chicago Press,

2008

The

Writer as Migrant

Nhà văn thiên di

Preface

Sometimes

it is difficult to

differentiate an exile from an immigrant. Nabokov was both an immigrant

and an

exile. But to the great novelist himself, such a distinction was

unnecessary,

as he often maintained that the writer's nationality was "of secondary

importance" and the writer's art was "his real passport." In the

following chapters, my choice of the word "migrant" is meant to be as

inclusive as possible - it encompasses all kinds of people who move, or

are

forced to move, from one country to another, such as exiles, emigrants,

immigrants, and refugees. By placing the writer in the context of human

migrations, we can investigate some of the metaphysical aspects of a

"migrant writer's" life and work.

I make

references to many

works of literature because I believe the usefulness and beauty of

literature

lies in its capacity to illuminate life. In addition, I focus on

certain important

works-texts that may provide familiar ground for discussion. I will

speak at

length about some exiled writers, not because I view myself only as an

exile -

I am also an immigrant- but mainly because the most significant

literature

dealing with human migration has been written on the experience of

exile. By

contrast, immigration is a minor theme, primarily American. Therefore,

a major

challenge for writers of the immigrant experience is how to treat this

subject

in response to the greater literary traditions.

My observations are merely

that-my observations. Every individual has his particular

circumstances, and

every writer has his own way of surviving and practicing his art. Yet I

hope my

work here can shed some light on the existence of the writer as

migrant. That

is the purpose of this book.

Lời nói

đầu

Đôi khi thật khó mà phân

biệt

giữa lưu vong, và nhập cư. Nabokov là cả hai, nhập cư và lưu vong.

Nhưng nhà văn

lớn lao này coi một sự phân biệt như thế là không cần thiết, quốc tịch

là thứ

yếu, nghệ thuật mới là căn cước thực sự của nhà văn. Trong những chương

sau

đây, khi chọn từ thiên di, tôi muốn ôm lấy đủ kiểu dời đổi, hay bắt

buộc phải dời

đổi từ một xứ sở này qua một xứ sở khác, nào là lưu vong, nào là di cư,

nào là

nhập cư nào là tị nạn. Bằng cách đặt nhà văn vào cái thế thiên di

như thế chúng

ta có thể điều tra, nghiên cứu một vài khiá cạnh siêu hình của cuộc

sống của

một nhà văn thiên di, và tác phẩm của người đó….

Tôi viện dẫn nhiều tác phẩm

văn học, bởi vì tôi tin tưởng, sự hữu ích

và vẻ đẹp

của văn chương nằm ở trong khả năng làm sáng lên cuộc sống của nó. Tôi

xoáy vào

một số tác phẩm quan trọng - những bản văn có thể cung cấp một mảnh đất

chung để

bàn luận. Tôi sẽ nói nhiều về một số nhà văn lưu vong, không phải vì

tôi tự coi

mình là một trong số đó – nhưng chủ yếu là vì thứ văn chương có ý nghĩa

nhất bàn

về sự thiên di của con người thì được viết về kinh nghiệm lưu vong.

Ngược lại, nhập

cư chỉ là một đề tài thứ yếu, và là của Mỹ. Từ đó, thách đố lớn lao đối

với những

nhà văn viết về kinh nghiệm nhập cư, là, làm sao từ một kinh nghiệm thứ

yếu như

vậy mà có thể đáp ứng với những truyền thống văn chương lớn lao hơn.

Những nhận xét của tôi thì

chỉ

là của tôi. Với mỗi một cá thể nhà văn là những hoàn cảnh cá biệt của

người đó,

và mỗi nhà văn có một cách riêng của mình để sống sót và hành xử nghệ

thuật của

mình. Tuy nhiên, tôi hy vọng tác phẩm của tôi sẽ soi sáng được phần nào

về sự

hiện diện của nhà văn như là một kẻ thiên di. Đó là mục tiêu của cuốn

sách này.

*

Chuẩn vị hồ

sơ dự Nobel

Nếu muốn

đi đường tắt thì

sử dụng con đường của Gao Xingjian (Pháp-Tầu) hoặc Imre Kertész (Hung)

hay

Orhan Pamuk (Thổ) tuy nhiên con đường này cũng rất là gay go, nhiều khi

phải bỏ

quê cha đất tổ chạy trốn ra nước ngoài.

Người viết xin khuyên : Chớ nên chọn lựa

con đường tắt

này.

Nguồn

Viết thế này, thì nên đổi

tên blog là Ngộ Độc Văn

Chương!

Cũng trên blog này đã có lần nhét vô miệng ông nhà văn

Nhật Murakami, câu tuyên bố, hồi hai muơi tuổi, mê thiên đường Liên Xô

quá, ông đã hăm he dịch tác phẩm Ruồi

Trâu, sự thực, ông mê Fitzgerald và tính dịch The Great Gatsby, nhưng tự lượng

chưa đủ nội lực tiếng Anh, nên mãi sau này, mới dám dịch nó.

Giả như liều lĩnh, như dịch giả TL chẳng hạn, thì Nhật cũng đã có một

Đại gia Murakami từ hồi nào rùi!

*

Nhưng quái đản nhất, là,

khi thấy sai sót, Gấu lập tức thông báo trang chủ, vì nghĩ, một sai sót

như thế ảnh hưởng tới mọi anh chị Mít, nhưng lạ làm sao, trang chủ tỉnh

bơ, như người Hà Lội!

Trong khi đó, Tin Văn,

mỗi lần được độc giả hạ cố chỉ cho sai sót, còn mừng hơn cả chuyện được

độc giả xoa đầu!

*

Tay tác giả bài viết trên blog của Nguyễn Thi

Sĩ, hẳn là

chưa từng đọc ba nhà văn trên. Nên cứ đinh ninh là họ, do viết văn

chống đối nhà

nước của họ, nên phải bỏ chạy, và nhờ vậy được phát Nobel, và chỉ vì

muốn được

Nobel nên mới làm như vậy. Đọc bài viết, thì có vẻ như cũng rành tiếng

Anh tiếng

U cũng nên, nhưng “thư ký thường trực” khác “thư ký vĩnh viễn”. Mấy ông

hàn thì

“vĩnh viễn”, nhưng ai cấm mấy ông này quit job đâu?

Đúng là điếc không sợ súng.

Hình như vào thời đại net, ai

cũng có quyền mở blog, nên mới xẩy ra tình trạng này? Gấu nghi, chắc

không phải,

mà là hậu quả của một thế giới bị bịt kín lâu quá, thí dụ xã hội Miền

Bắc, đột

nhiên mọi cửa đều được mở ra, trước đám quyền chức, và con cái của họ,

luôn cả đám

tinh anh, tức mù dở trong đám mù.

Chứng cớ, sự ngu dốt của mấy

anh Yankee mũi tẹt làm cho đài Bi Bì Xèo, chẳng hạn.

Một người viết trong số họ

đã dùng hình ảnh, cái lỗ hổng không làm sao lấp đầy,

đúng quá, nhưng

khi người

này dùng, là để nhắm vào PTH, thế mới khổ!

Ngay cả

nhận xét của tay "thư

ký vĩnh viễn", về văn chương Mẽo cũng đâu có sai. Ha Jin, nhà văn

Mẽo gốc

Trung Quốc cũng nghĩ như vậy. Ông viết, trong bài The Writer as Migrant, Nhà văn thiên

di, Tin Văn

đang giới thiệu:

Ngược lại, nhập cư chỉ là một

đề tài thứ yếu, và là của Mỹ. Từ đó, thách đố lớn lao đối với những nhà

văn

viết về kinh nghiệm nhập cư, là, làm sao từ một kinh nghiệm thứ yếu như

vậy mà

có thể đáp ứng với những truyền thống văn chương lớn lao hơn.

Nhà văn Mít, theo Gấu muốn

được Nobel, là phải đối diện với vấn đề nhức nhối nhất hiện nay của văn

chương

và đồng thời xã hội Mít: Tại sao cuộc chiến thần kỳ

như thế, mà kết quả lại khốn khổ khốn nạn như thế.

Vả chăng hình như muốn là ứng

viên của Nobel, phải có đại gia, hội đoàn... tiến cử, giống như ở Việt

Nam,

muốn ứng cử là phải được Đảng và Mặt Trận Tổ Quốc OK, không thể độc

diễn như

Tông Tông Thiệu được. Vấn đề này Gấu không "xua" vì, chưa khùng đến

mức như vậy!

*

Nobel 2004

Đọc

Jelinek

Có

thể bà chẳng tin rằng thế giới này có thể là một nơi chốn tốt đẹp hơn,

nhưng bà

giận dữ, rằng cớ làm sao nó lại khốn kiếp như vậy. Bà rất bực,

theo một

cách thế đạo đức. Tôi gần như chỉ mong, được như bà.

Nobel

Sám Hối

[Nhân

bài dịch của Thụ Nhân, trên e-Văn, về giá trị giải Nobel văn

chương]

Việc trao giải Nobel cho một nhà văn chẳng mấy ai biết, thí dụ như năm

nay, và

luôn cả mấy năm trước, theo thiển ý, là một trong những chuyển hướng

lớn lao nhất

của Hàn Lâm Viện Thụy Điển, và - vẫn theo thiển ý – nó xoay quanh trục

Lò

Thiêu, và câu nói nổi tiếng của nhà văn, nhà học giả Đức gốc Do Thái,

Walter

Benjamin, một nạn nhân của Nazi: Mọi tài liệu về văn minh là một tài

liệu về dã man.

Mượn hơi men từ câu của ông, ta có thể cường điệu thêm, và nói, Nobel

mấy năm gần

đây, là Nobel của văn chương sám hối.

Khi Kertesz được Nobel, ngay dịch giả qua

tiếng Anh

hai tác phẩm của ông, trong có cuốn Không Số Kiếp, cũng không nghĩ tới

chuyện

ông được Nobel. Katharina Wilson, dạy môn Văn Chương So Sánh

(Comparative

Literature, Đại học Georgia), trong một cuộc phỏng vấn, ngay sau khi

biết

Kertesz được Nobel, cho biết, bà thực sự không tin, không thể tưởng

tượng được

lại có chuyện đó. "Tôi luôn luôn nghĩ, đây là một nhà văn hảo hạng

(first

rate), một thiên tài theo kiểu của ông ta, nhưng tôi chẳng hề tin, ngay

cả chuyện

ông được đề cử (nominated), đừng nói đến chuyện được giải Nobel."

Khi Cao Hành Kiện được, cả khối viết văn bằng tiếng Anh dè bỉu, chưa kể

đất mẹ

của ông, là Trung Quốc, cũng nổi giận: Thứ đó mà cũng được Nobel, hử?

Rõ ràng

là có mục đích chính trị!

Nhưng Nobel quả là có mục đích chính trị, và đây mới là chủ tâm của nó,

theo

tôi. Chính trị như là đỉnh cao của văn chương, chính trị theo nghĩa của

câu nói

của Benjamin dẫn ở trên.

Hãy nhớ lại những lời tố cáo nước Áo của bà Elfriede Jelinek,

[Bà gây

tranh cãi nhiều nhất vào năm 1980 khi được trích lời nói là

"Áo

là một quốc gia tội phạm", nhắc lại chi tiết quốc gia bà

từng

tham gia vào các tội ác của phát xít Đức. Trích BBC online], là

chúng

ta nhận ra sự sám hối của giải Nobel.

Trong

số những người cùng được vinh danh với bà, có Walter Benjamin. Có đế

quốc Áo

Hung, mà những nhà văn Jopseph Roth [Đức gốc Do Thái], đã từng coi như

đây là “nhà”

của mình, hay như Freud đã từng than [qua bài

viết của

J. M. Coetzee, điểm Tập Truyện Ngắn của Joseph Roth, The Collected

Stories]:

“Áo

Hung không còn nữa”, Sigmund Freud viết cho chính mình, vào

Ngày Đình Chiến, năm 1918: “Tôi không muốn sống ở bất cứ một nơi nào

khác… Tôi

sẽ sống trong què cụt như vậy, và tưởng tượng mình vẫn còn đầy đủ tứ

chi.” Ông

nói không chỉ cho chính ông mà còn cho rất nhiều người Do Thái

của văn

hóa Áo-Đức....

Cũng vậy khi trao cho Cao Hành Kiện là vinh danh sự sống sót của “chỉ"

một con

người, trong

cuộc chiến chống lại lịch sử của đám đông.

Với riêng tôi, mấy giải Nobel những năm gần đây mới thực sự là Nobel

văn

chương.

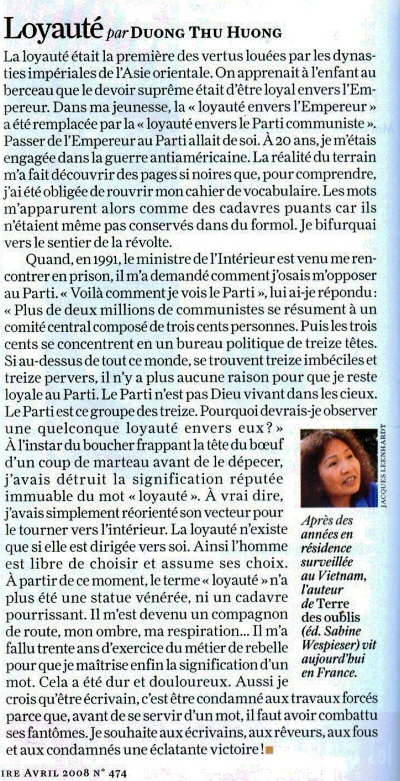

Nhìn theo đường hướng đó, nhà văn Việt Nam hy vọng đoạt giải văn

chương

Nobel nhất, trong tương lai, có thể là Dương Thu Hương.

Chắc chắn sẽ lắm người phản đối. Có thể “cả một quốc gia” phản

đối. Thứ

đó, đâu phải văn chương, mà là chính trị, mà là phản động, mà là…

Nhưng

như đã nói ở trên, Nobel là chính trị trước đã. Phải có “cái tâm”, rồi

hãy, viết

gì thì viết.

Nhật Ký Tin Văn

Thông thường, Viện Hàn lâm đề

cao những nhà văn cánh tả như Sinclair Lewis, Gunter Grass, Jose

Saramago,

Pablo Neruda hoặc Jean-Paul Sartre. Những nhà văn Mỹ từng giành giật

được giải

thưởng này là một nhóm khá pha tạp như: tác giả chống tư bản John

Steinbeck,

nhà văn hạng xoàng Pearl S. Buck.

Đề

cao những nhà văn cánh

tả, vậy mà đề nghị nên huỷ bỏ ư?

*

Việc

trao giải

Nobel cho một nhà văn chẳng mấy ai biết, thí dụ như năm nay, và luôn cả

mấy năm

trước, theo thiển ý, là một trong những chuyển hướng lớn lao nhất của

Hàn Lâm

Viện Thụy Điển, và - vẫn theo thiển ý – nó xoay quanh trục Lò Thiêu, và

câu nói

nổi tiếng của nhà văn, nhà học giả Đức gốc Do Thái, Walter Benjamin,

một nạn

nhân của Nazi: Mọi tài liệu về văn minh là một tài liệu về dã man.

Nhưng,

có lẽ phải nghe Cao

Hành Kiện phán, thì chúng ta mới nhận ra, giải Nobel trong những năm

gần đây, quan trọng như thế nào.

- Entry for August 02, 2008

-

Gao Xingjian. Photograph: Mike Clarke/AFP/Getty

In May this year, when news of the Sichuan

earthquake reached the Nobel laureate Gao Xingjian at his home in

Paris, he remembered living through a similar disaster in China more

than 30 years ago: "Even though I was quite far away then, I was

terrified." That earthquake, in Tangshan, near Beijing, was one of the

20th century's worst in terms of lives lost. "Afterwards there were

terrible downpours, but no one wanted to stay in the buildings. I can

imagine the fear in Sichuan."

It was the tail-end of the cultural revolution, the

collapse of which was accelerated by the aftermath of the 1976 quake.

When the 10-year terror began in 1966, Gao felt compelled to burn a

suitcase-full of all his manuscripts since adolescence, in case he was

denounced. But he was still sent for "re-education" in the countryside.

Labouring in the fields, he began again, hiding his work in a hole in

the ground, when "to write, even in secret, was to risk one's life". As

Gao said in 2000 when he became the first (and only) writer in Chinese

to win the Nobel prize for literature, "it was only during this period,

when literature became utterly impossible, that I came to comprehend

why it was so essential."

Gao, who was first published when he was almost 40,

has written more than 20 plays, short stories, essays, criticism and

two semi-autobiographical novels: Soul Mountain (1990), based on a

journey down the Yangtse river; and One Man's Bible (1999), memories of

the cultural revolution spliced with episodes in the life and loves of

a world-famous man of the theatre. The novels were translated into

English in 2000 and 2002, followed by Buying a Fishing Rod for My

Grandfather (2004), a collection of short stories. His Nobel lecture is

the title essay of The Case for Literature (2007). Yet since 1989 all

his work has been banned in mainland China (most has been published in

Taiwan).

A pioneer of experimental theatre in China in the

early 1980s, Gao fell foul of renewed purges, and left for Germany,

then France in 1987. But it was his reaction to the Tiananmen Square

massacre in 1989 that he believes sealed his fate. "I heard the news on

the radio that people were gunned down, and right then, I knew I was

looking at exile," he says. He condemned the crackdown on French

television, publicly resigned from the Chinese Communist party he had

joined in 1962, tore up his Chinese passport and applied for political

asylum. He has lived in Paris for 21 years as a painter and

writer/director, becoming a French citizen in 1998.

For Jung Chang, Gao has "immortalised the memories

of a nation suffering from forced amnesia; my own memories flooded back

reading him". Ma Jian, the London-based author of Beijing Coma, sees

Gao as "both a linguistic innovator and a writer of integrity, whose

work constantly reaffirms the importance of the individual over the

collective. He was one of the first writers of the post-Mao era to

absorb developments in western literature and philosophy, and meld them

with Chinese classical traditions to create a new kind of drama and

fiction." By contrast, the critic Julia Lovell commends his shorter

fiction yet feels the novels are a "sprawling, self-indulgent take on

the horrors of political oppression".

Aged 68, Gao lives in Paris's 2nd arrondissement

with Céline Yang, a novelist who left China after 1989. Gao, who also

writes in French, has translated and directed plays in his adopted

language, and was awarded the Légion d'honneur in 2000. He sees himself

as a "fragile man who has managed not to be crushed by authority and to

speak to the world in his own voice". As he pointed out recently at

Warwick University, on a rare visit to Britain, most of his life's work

has been done since leaving China. While the Swedish academy saw him as

a "perspicacious sceptic" possessed of "bitter insights", for Ma, Gao

is a "tranquil yet engaged presence; a very composed, mild-mannered

man, but a passionate reader and artist". Speaking in French, smiling

readily though he seems frail, Gao recalls the Nobel prize as a

"whirlwind. I was carried away, and it was difficult to organise my

life. Very soon after, I fell ill, and had two big heart operations one

after the other. It was because of the fatigue and pressure. I became

an ornament on the political scene."

The official Chinese reaction to the Nobel was

predictably hostile. The head of the Chinese Writers' Association said

the prize had been "used for political purposes and thus has lost its

authority". According to Ma, that body had "campaigned for years for

the Nobel prize to be awarded to one of their state-sanctioned writers,

so they were furious when it went to a political exile". Yet Gao has

also been attacked by dissidents - notably for his play Escape (1989),

written within months of the Tiananmen Square massacre, and the

ostensible trigger for all his work being banned in China. Its three

characters take refuge from the army crackdown in a warehouse, amid

sexual tensions and cynicism about self-proclaimed heroes. "Exiled

writers said my play blackened the democracy movement," Gao says. "Even

today, those attacks continue." In Ma's view, "It was criticised by the

pro-democracy activists because it failed to show the students in a

heroic light."

According to Gao, a writer's only responsibility is

"to the language he writes in". Determined to rid himself of others'

ideologies, to live, as he says, "without isms", he advocates a "cold

literature", detached from both political agendas and consumerist

pressures, whose purpose is to bear witness. His essays express a

loathing for Nietzsche's idea of the Superman and and its hold over

Chinese thought. "Many intellectuals feel themselves to be Supermen who

are spokesmen for the people," he says. "But in my opinion, they're to

be pitied. Under Mao's dictatorship, these poor sheep suffered the same

fate as everyone else. I don't want to be a strong hero who can save

society. I just want to save myself."

He was born in 1940, the eldest of two brothers, in

Ganzhou. Shortly after the Communist revolution of 1949, the family

moved to Nanjing. His father was a senior employee in the Bank of

China, and his mother an amateur actor. It was a "well-to-do, protected

childhood, and my parents were very open-minded - which was rare. It's

like a lost paradise." His mother read western literature in

translation, from Balzac and Zola to Steinbeck, and he grew up with

both western and Chinese classics. His love of theatre comes from his

mother, with whom he first acted on stage, aged five. She also

encouraged him to keep a diary. But when Gao was 20, during the "great

leap forward", she drowned at a rural labour camp. "Even though she

wasn't really an intellectual, she was sent away for re-education just

like all the others who were not from Communist 'red' families," he

says.

As a child he played the violin and flute, and

painted, but opted to study French literature at the Beijing Foreign

Languages Institute, drawn to such dramatists as Genet and Artaud.

After graduating in 1962, he worked at the Foreign Languages Press,

translating French classics. But in 1966-76, all foreign-language books

were banned.

In One Man's Bible, the narrator is both participant

in the cultural revolution and victim. After protesting against Red

Guards' beating of a colleague at his workplace, Gao was treated as a

hero, and led a rival Red Guard faction. The Red Guard, he explains,

was initially composed of "children of high-up party executives, who

felt like mowing down and killing old people like their parents. Other

youths reacted and set up a rebellious Red Guard faction. All young

people, to protect themselves, had to join one or the other. But once I

got in, I saw it wasn't really a way out. Experience has taught me that

any kind of political grouping is oppressive. It's the blind mass that

crushes the individual."

The novel also reflects Gao's experience of being

informed on by his first wife. On this he will say nothing, other than

to allude to Stalinist Russia and East Germany. After Mao's death in

1976, Gao translated Beckett and Ionesco, and visited France and Italy.

In his first book, essays on the modern novel, he took issue with Mao's

guidelines for literature urging didactic, realist art. In Ma's view,

the book "influenced a generation of writers by introducing them to the

concepts of stream of consciousness, surrealism and black humour." Gao,

Ma adds, was "the 'elder brother' of the small band of dissident

Beijing artists and writers that I belonged to. He could speak foreign

languages and had travelled abroad. We all looked up to him."

Made artistic director of the People's Art Theatre

in Beijing in 1981, Gao broke with realism in experimental plays such

as Absolute Signal (1982), about the change of heart of a would-be

train robber. It startled Ma by exploring, "in a nuanced way, the

psychology of a 'bad' individual. It heralded a new kind of drama, in

opposition to the one-dimensional propaganda of the cultural

revolution". Yet Gao became an early casualty of a renewed drive in

1983 against "spiritual pollution" and western modernism. His play Bus

Stop (1983), a take on Waiting for Godot, was banned after 10

performances.

"I'd already self-censored," Gao says. "Then I was

censored by others. That's when I decided to write just for myself."

His resolve coincided with being diagnosed with lung cancer - the

disease from which his father had died. "After Bus Stop, they

threatened to send me back to work camp. Then this shadow was found on

my lungs. I went back to my hometown and had more tests - and by a

miracle it had disappeared." The reprieve made him realise that "if you

want to do anything, do it now, without compromise or concession,

because you have only one life."

He fled to the forest highlands of south-west China,

ostensibly to research woodcutters' lives. For five months he tracked

the Yangtse riverfrom its source, from Sichuan's giant panda reserve to

the China sea. "I was looking for a place of refuge. It was also a

spiritual and cultural quest, to find the origin of Chinese culture,

the source that had not yet been polluted by politics." The result,

completed in Paris after more of his plays had been banned in rehearsal

in Beijing, was Soul Mountain, which took seven years to write.

The novelist and film-maker Xiaolu Guo read a

pirated copy and found it "very beautiful and poetic - intimate but

epic". "The novel in Chinese sensibility is 2,000 years old," she says.

"It's the language of real people from the streets - the non-official

version." For Gao, the "tiny history of a few individuals in a novel

can't be revised or manipulated. It goes to the heart of human nature.

If it's still read, it's still valuable."

Though it reads like an autobiographical monologue,

Soul Mountain shifts viewpoints - a technique repeated in One Man's

Bible and Gao's plays. "Literature can't merely be an expression of

self - that would be unbearable," Gao says. "You have to be critical

not just of society and others, but of yourself: each subject has three

pronouns: 'I', 'you', and 'he' or 'she'." He sees such self-scrutiny as

a safeguard: "If you're not perfectly conscious of yourself, that self

can be tyrannical; in relationship to others, anyone can become a

tyrant. That's why no one can be a Superman. You have to go beyond

yourself with a 'third eye' - self-awareness - because the one thing

you cannot flee is yourself. That's why Greek tragedy is still the

tragedy of human beings today."

Gao's later plays have been called a modern Zen

theatre, combining modernist techniques with traditional Chinese drama

and ritual, from masks and shadow play to opera. They have been widely

staged in Europe, Taiwan and Hong Kong - where Tales of Mountains and

Seas (1993) premiered in June at a festival devoted to Gao's work. But

they are rarely seen in the English-speaking world. Escape was

commissioned by a US theatre company, but premiered in Sweden after Gao

refused to revise it. "When the company asked me to change the text, I

understood what they wanted: there was no American-style hero," he

says. "I said, no. Even the Chinese Communist party couldn't make me

change a play; why should I accept correction from America?"

It was while directing his modern take on a Peking

opera, Snow in August (2002), in Taiwan, that Gao collapsed and later

had major heart surgery. In Marseilles rehearsing his play The Man Who

Questions Death (2003), he collapsed again. He has co-directed a

90-minute film, Silhouette/Shadow (2006), that reflects his brush with

death. Showing him painting, reciting poetry and rehearsing actors, it

captures a flow of images and memories as he is rushed to hospital in

an ambulance. A "cinepoem or modern fable - neither fiction nor

autobiography nor documentary", it was filmed over four years, without

funding. "Since childhood I'd dreamed of making a film, but producers

in France and Germany wanted to make commercial films with chinoiserie.

I refused."

The film, which has no dialogue and might be

released only on the internet, is part of a life's

experimentation.Though he enjoys dancing, swimming in the sea and

cooking seafood, Gao says he works "non-stop, 12 hours a day", and

never takes summer holidays "or even weekends, because freedom of

expression is so precious to me".

The market pressures China now shares with the west

are, he believes, "harder to resist than political and social customs".

He feels lucky that his ink paintings were selling in Europe before he

fled, and have been widely exhibited. "I could make a living, so I

could write books that didn't sell much. I always understood that

literature can't be a trade; it's a choice." Painting, he says, "begins

where language fails", and he works listening to music - often Bach. Ma

sees his paintings as "infused with the still, reflective quality of

Zen Buddhism that I think he strives to achieve in his writing."

To Ma, who believes that One Man's Bible is about

the "burden of painful memories, and how they corrupt the present and

destroy oneself and those around one", it is a "tragedy that a writer

of such calibre is condemned in his own homeland". Guo feels Gao's

voice is crucial for its "stubborn, personal view of our history. The

kids born after the 1980s know nothing about the past - the tragedy and

sorrow of my father's generation - and how society dedicated to a

collective dream ruined people and invaded their lives."

Gao sees his work as an affirmation of the self in

the face of efforts to extinguish it. Recalling a time when it was

"impossible to say freely what you thought, even in your family", he

says: "Everything people say in those circumstances is false; everybody

is wearing a mask. It's in literature that true life can be found. It's

under the mask of fiction that you can tell the truth."

Gao on Gao

"Without Isms is neither nihilism nor eclecticism;

nor is it egotism or solipsism. It opposes totalitarian dictatorship

but also opposes the inflation of the self to God or Superman. It hates

seeing other people trampled on like dog shit. Without Isms detests

politics and does not take part in politics, but is not opposed to

other people who do. If people want to get involved in politics, let

them go right ahead. What Without Isms opposes is the foisting of a

particular brand of politics on to the individual by means of abstract

collective names such as 'the people', 'the race' or 'the nation'."

(The idea behind it is that we need to bid goodbye

to the 20th century, and to put a big question mark over those "isms"

that dominated it.)

· From The Case for Literature, translated by Mabel

Lee, published by Yale University Press

*

By Orville Schell

Dark Matter

a film directed by Chen Shi-Zheng

Olympic Dreams: China and Sports, 1895–2008

by Xu Guoqi

Harvard University Press, 377 pp., $29.95

China's New Confucianism: Politics and Everyday

Life in a Changing Society

by Daniel A. Bell

Princeton University Press, 240 pp., $26.95

China's New Nationalism: Pride, Politics, and

Diplomacy

by Peter Hays Gries

University of California Press, 215 pp., $21.95 (paper)

China's Great Leap: The Beijing Olympic Games and

Olympian Human Rights Challenges

Edited by Minky Worden, with an introduction by Nicholas Kristof

Seven Stories, 231 pp., $18.95 (paper)

Living without 'isms

''It's in literature that true life can be found. It's under the mask

of fiction that you can tell the truth'

The idea behind it is

that we need to bid goodbye to the 20th century, and to put a big

question mark over those "isms" that dominated it

Sống đếch cần Ism!

Chính là trong văn chương mà đời thực có thể tìm kiếm thấy.

Note: Một bài phỏng

vấn tuyệt vời. Tin Văn sẽ đi bản dịch trong những kỳ tới.

Tình cờ làm sao: Bạn phải đọc bài này cùng lúc với bài trên NYRB, China: Humiliation & the Olympics TQ: Nhục Nhã &

Olympics rồi suy ra trường hợp

mấy anh Yankee mũi tẹt “Hà Lội ta hiên ngang ngửng đầu”, rồi đọc bài

viết của DTH, "Trung thành với Đảng" là cái đếch gì, thì mới đã! NQT

Loyauté

par DUONG THU HUONG

Trung

Trung là đức tính đầu

tiên của những triều đại phong kiến Đông phương đòi hỏi ở thần tử, phải

trung với vua. Ngay từ khi nằm nôi, con nít Á Châu đã được học điều

này. [Khi nghe tin Stalin chết, đứa trẻ con ngày nào ở trong Tố Hữu

sống dậy, và thốt lên, "Tiếng đầu lòng con gọi Stalin", là do đó]. Ngay

từ khi còn trẻ, với tôi, trung với vua được thay thế bằng trung với

Đảng Cộng Sản. Từ Vua qua Đảng là một quá trình tự thân. Vào lúc 20

tuổi tôi lao vào cuộc chiến chống Mỹ. Thực tại thực địa làm tôi khám

phá ra những trang quá đen tối, đến nỗi tôi lại phải mở ra cuốn tự vựng

của mình, để tìm hiểu. Những từ ngữ hiện ra như những xác chết thối

rữa, vì không được ướp formol. Tôi bước qua ngả đường nổi loạn.

Năm 1991, tên bộ trưởng Nội vụ đến gặp tôi trong nhà tù. Hắn hỏi tôi,

sao dám chống Đảng. "Mi nghe đây bà nói đây này. Hơn hai triệu thằng CS

bợ lên một uỷ ban trung ương gồm ba trăm thằng. Rồi ba trăm thằng này

bợ lên một bộ chính trị gồm 13 cái đầu ngu đần. Nếu ngất ngưởng ở trên

đầu thế gian, là 13 tên ngu đần, bại hoại này, thì chẳng có lý do gì để

mà bà trung thành với Đảng. Đảng đâu phải là ông Giời sống ở trên Giời.

Đảng là một nhóm 13 tên. Tại sao bà lại phải trung với chúng?". Vào lúc tên đồ tể vung búa chặt

đầu con bò, trước khi xả thịt nó, là tôi hết còn tin vào chữ “trung”.

Đúng ra, tôi đổi hướng nó: trung chỉ có nghĩa khi mình vận nó vào chính

mình. Và như thế, con người tự do chọn lựa và đảm nhận những chọn lựa

của mình. Kể từ lúc đó, “trung” không còn là một thánh tượng tôn thờ,

cũng không phải là xác chết thối rữa. Nó trở thành bạn đường của tôi,

cái bóng của tôi, hơi thở của tôi…. Phải mất ba chục năm làm giặc tôi

mới hiểu và làm chủ được, ý nghĩa của một từ. Thật đau thương. Cũng

vậy, tôi nghĩ, là nhà văn là kẻ bị kết án khổ sai, bởi vì, trước khi sử

dụng một từ, phải chiến đấu với những bóng ma của nó. Tôi chúc những

nhà văn, những kẻ mơ mộng, những kẻ khùng điên, và những kẻ bị kết án

một chiến thắng huy hoàng. DTH

Saturday

August 2, 2008 - 09:40pm

(ICT) Remove

Comment

|

|