GRANTA

WHEN THERE

IS TALK OF 1945

Ryszard

Kapuscinski

TRANSLATED

FROM THE POLISH BY IKLARA GLOWCZEWSKA

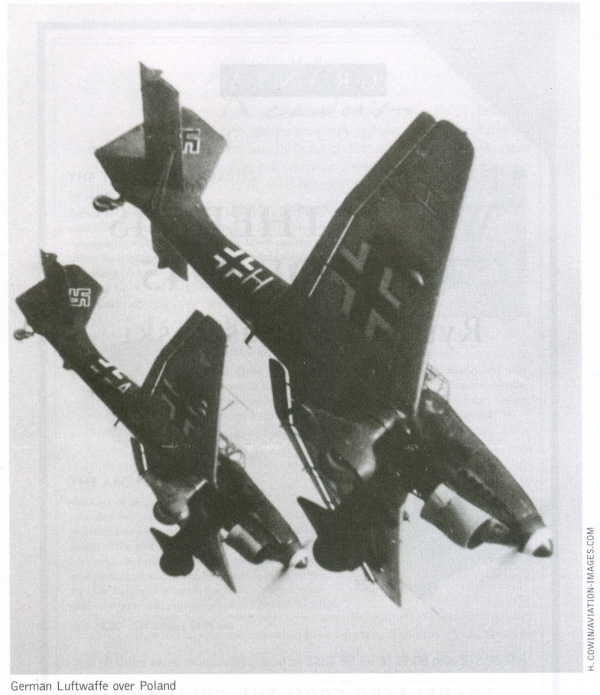

Total war

has a thousand fronts; during such a war, everyone is at the front,

even if

they never lie in a trench or fire a single shot. When I go back in

memory to

those days, I realize, not without a certain surprise, that I remember

the

beginning of the war better than its end. Its onset is clearly "fixed

for

me in time and place. I can conjure up its image without difficulty

because it

has retained all its colors, all its emotional intensity. It starts

with my

suddenly noticing one day, in the azure sky of a summer's ending (and

the sky

in September 1939 was wondrously blue, without a single cloud),

somewhere very,

very high up, twelve glittering silver points. The entire bright, lofty

dome of

the sky fills with a dull, monotonous rumble, unlike anything I've ever

heard

before. I am seven years old, I am standing in a meadow in eastern

Poland, and

I am staring at the points that are barely moving across the sky.

Suddenly,

there's a dreadful bang close-by, at the edge of the forest. I hear

bombs

exploding. It is only later that I learn they are bombs, for at this

moment I

do not yet know that there is such a thing as a bomb; the very notion

is

foreign to me, a child from the deepest provinces who had never even

listened

to a radio or gone to the movies, who didn't know how to read or write,

who had

never heard of wars and deadly weapons. I see gigantic fountains of

earth

spraying up into the air. I want to run towards this extraordinary

spectacle

which stuns and fascinates me, because, having as yet no wartime

experiences, I

am unable to connect into a single chain of cause and effect those

shining

silver planes, the thunder of the bombs, the plumes of earth flying up

to the

height of the trees, and the danger of imminent death. I start to run

there,

towards the forest and the falling and exploding bombs, but a hand

grabs me

from behind and throws me to the ground. 'Lie still!' I hear my

mother's

shaking voice. 'Don't move!' And I remember my mother, as she presses

me close

to her, saying something I don't understand and which I want to ask her

about

later. She is saying, 'There's death over there, child.'

It's night

and I'm sleepy, but I am not allowed to sleep; we must run, we must

escape.

Where to, I don't know. But I do understand that flight has suddenly

become

some sort of higher necessity, a new form of life, because everyone is

fleeing.

All the highways, roads, even country paths are full of wagons,

carriages, and

bicycles; full of bundles, suitcases, bags, buckets; full of terrified

and

helplessly wandering people. Some are making their way to the east,

others to

the west, still others to the north and the south. They run in all

directions,

circle about, collapse from exhaustion, fall asleep anywhere they can,

and

then, having caught their breath for a moment, they summon what's left

of their

strength and start once again their confused and endless journey.

I am

supposed to hold my little sister tightly by the hand. We can't get

lost, my

mother warns. But I sense, even without her saying it, that the world

has

suddenly become dangerous, foreign and evil, and that one must be on

one's

guard. I walk with my sister next to the horse-drawn wagon; it is a

simple

wooden cart lined with hay, and high up on the hay, on a linen sheet,

lies my

grandfather. He is paralysed and cannot move. When an air raid starts,

the

panicked crowd, until then patiently trudging along, dives for the

shelter of

the ditches, hides in the bushes, drops down in the potato fields. On

the

empty, deserted road only the wagon remains, and on it my grandfather.

He sees

the planes coming towards him, sees them abruptly descending, sees them

taking

aim at the abandoned wagon, sees the fire of the on-board guns, hears

the roar

of the machines over his head. When the planes vanish, we return to the

wagon

and mother wipes my grandfather's perspiring face. Sometimes there are

air

raids several times a day. After each one, sweat trickles down my

grandfather's

exhausted face.

We find

ourselves in an increasingly bleak landscape. There is smoke along the

distant

horizon, we pass empty settlements, lonely, burned-out houses. We pass

battlefields strewn with abandoned implements of war, bombed out

railway

stations, overturned cars. It smells of gunpowder, of burnt things, of

rotting

meat. We encounter dead horses everywhere. The horse-a large,

defenseless

animal - doesn’t know how to hide; during a bombardment it stands

motionless,

awaiting death. There are dead horses in the roads, in ditches, in the

fields a

bit further out. They lie there with their legs up in the air, as if

shaking

their hooves at the world. I don't see dead people anywhere; they are

quickly

buried. Only the horses-black, bay, piebald, chestnut-lie where they

stood, as

if this were not a human war but a war of horses; as if it were they

who had

waged among themselves a battle to the death and were its only victims.

A cold and

hard winter arrives. Under difficult circumstances, one feels the cold

more

keenly; the chill is more penetrating. Winter can be just another

season, a

waiting for spring; but now winter is a disaster, a catastrophe. That

first

winter of the war is truly bitter. In our apartment the stoves are cold

and the

walls covered with thick white frost. There is nothing to burn; there

is no

fuel to buy, and it's too dangerous to steal any. It's death if you're

caught

filching coal or wood. Human life is worth little now, no more than a

lump of

coal or a piece of kindling. We have nothing to eat. Mother stands

motionless

for hours at the window, staring out. You can see people gazing out at

the

street like this in many windows, as if they were counting on

something,

waiting for something. I roam around the yards with a group of boys,

neither

playing nor explicitly hunting for something to eat; that would mean

hope and

then disappointment. Sometimes the smell of warm soup wafts through a

door.

When that happens one of my friends, Waldek, sticks his nose into the

crack and

begins feverishly to inhale the odor and to rub his stomach with

delight, as if

he were sitting at a sumptuously laid table. A moment later he grows

sad again,

and listless.

One day we

hear that they are going to be giving away candy in a store near the

square. We

immediately line up-a string of cold and hungry children. It's the

afternoon

already, and getting dark. We stand all evening in the freezing

temperatures,

then all night and all the following day. We stand huddled together,

hugging

each other for a little bit of warmth, so as not to freeze. Finally the

store

opens, but instead of candy we each get an empty metal tin that once

used to

contain fruit drops. Weak, stiff from the cold and yet, at that moment,

happy,

I carry home my booty. It is valuable because a residue of sugar still

remains

on the inside walls of the can. My mother heats up some water, pours it

into

the can, and we have a hot, slightly sweet beverage: our only

nourishment that

day.

Then we are

on the road again, travelling westwards from our town, Pinsk, because

my mother

has heard that our father is living in a village outside Warsaw. He was

captured at the front, escaped, and is now, we think, teaching children

in a

small country school. When those of us who were children during the war

recall

that time and say 'father' or 'mother', we forget, because of the

solemnity of

those words, that our mothers were young women and our fathers were

young men

and that they desired each other strongly, missed each other terribly,

and

wanted to be together. And so my mother sold everything in the house,

rented a

wagon, and we set off to search for our father. We found him by

accident.

Riding through the village called Sierak6w, my mother suddenly cries

out to a

man crossing the road: 'Dziudek!' From that day we live together in a

tiny room

without water or electricity. When it grows dark, we go to bed, because

there

aren't even candles. Hunger has followed us here from Pinsk. I search

constantly for something to eat-a crust of bread, a carrot, anything.

One day,

father, having no other recourse, tells his class: 'Children, whoever

wants to

come to school tomorrow must bring one potato.' Father didn't know how

to

trade, didn't know how to do business and received no salary, so he

decided he

had only one option: to ask his students for a few potatoes. Half the

class

don't show up the next day. Some children bring half a potato, others a

quarter. A whole potato is an enormous treasure.

Next to my

village lies a forest, and in that forest, near a settlement called

Palmira, is

a clearing. In this clearing SS men carry out executions. At first,

they shoot

at night and we are woken up by the dull, repetitive sound of gunfire.

Later,

they do it also by day. They transport the condemned in enclosed,

dark-green

trucks, with the firing squad bringing up the rear of the convoy in a

truck

without a covering.

The firing

squad always wear long overcoats, as if a long overcoat belted at the

waist

were an indispensable prop in the ritual of murder. When such a convoy

passes

by, we, the village children, observe it from our hiding place in the

roadside

bushes. In a moment, behind the curtain of trees, something that we are

forbidden to witness will begin. I feel a cold tremor running up and

down my

spine-I'm trembling. We wait for the sound of the salvos. There they

are. Then

come the individual shots. After a while the convoy returns to Warsaw.

The SS

men again bring up the rear. They are smoking cigarettes and talking.

At night the

partisans come. They appear suddenly, their faces pressed against the

window. I

stare at them as they sit at the table, always excited by the same

thought:

that there is still time for them to die tonight, that they are marked

by

death. We could, of course, all die, but they embrace the possibility,

confront

it head on. They come one rainy night in autumn and talk to my mother

in

whispers (I haven't seen my father for a month now, and won't until the

end of

the war; he's in hiding). We get dressed quickly and leave: there is a

round-up

taking place nearby and entire villages are being deported to the

camps. We

flee to Warsaw, to a designated hiding place. I see a large city for

the first

time: trams, multi-storey buildings, big stores. Then we are in the

countryside

again in yet another village, this time on the far bank of the Vistula.

I can't

remember why we went. I remember only walking once again next to a

horse-drawn

wagon and hearing the sand of the warm country road sifting through the

wheels'

wooden spokes.

All through

the war I dream of shoes. To have shoes. But how? What must one do to

get a

pair? In the summer I walk barefoot, and the skin of my soles is as

tough as

leather. At the start of the war father made me a pair of shoes out of

felt,

but he is not a shoemaker and the shoes look strange; besides, I've

grown, and

they are already too tight. I fantasize about a pair of big, strong,

hobnailed

shoes which make a distinctive noise as they strike the pavement. The

fashion

was then for high-topped boots; I could stare for hours at a

good-looking pair.

I loved the shine of the leather, loved listening to the crunching

sound it

made. But my dream of shoes was about more than beauty or comfort. A

good,

strong shoe was a symbol of prestige and power, a symbol of authority;

a shoddy

shoe was a sign of humiliation, the brand of a man who has been

stripped of all

dignity and condemned to a subhuman existence. But in those years all

the shoes

I lusted for trod past me in the street with indifference. I was left

in my

rough wooden clogs with their uppers of black canvas, to which I would

sometimes apply a crude ointment in an unsuccessful attempt to impart a

tiny

bit of lustre.

Late in the

war, I became an altar boy. My priest is the chaplain of a Polish Army

field

hospital. Rows of camouflaged tents stand hidden in a pine forest on

the left

bank of the Vistula. During the Warsaw Uprising, before the Russian

army moved

on the city in January 1945, an exhausting bustle reigns here.

Ambulances speed

in from the front lines, which rumble and smoke not far away. They

bring the

wounded, who are often unconscious and arranged hurriedly and in

disarray one on

top of the other, as if they were so many sacks of grain (only these

sacks are

dripping blood). The medics, themselves half dead from fatigue, take

the

wounded out, lay them on the grass, and then drench them with a fierce

spray of

cold water. Those that give some signs of life they carry into the

operating

tent (in front of this tent there is always a fresh pile of amputated

arms and

legs). Those that no longer move are brought to a large grave at the

rear of

the hospital. There, over that yawning tomb, I stand for hours next to

the

priest, holding his breviary and the cup with holy water. I repeat

after him

the prayer for the dead. 'Amen,' we say to each deceased, 'Amen,'

dozens of

times a day, but quickly, because somewhere beyond the woods the

machinery of

death is working non-stop. And then one day everything is suddenly

quiet and

empty-the ambulances stop coming, the tents disappear. The hospital has

moved

east. In the forest only the crosses remain.

And later?

The passages above are a few pages from a book about my wartime years

that I

began to write and then abandoned. I wonder now what the book's final

pages

would have been like, its conclusion, its epilogue. What would have

been

written there about the end of the Second World War? Nothing, I think.

I mean,

nothing conclusive. Because in some fundamental sense, the war did not

end for

me in 1945, or at any time soon afterwards. In many ways, something of

it

endures in me still. For those who lived through it, war is never over,

not in

an absolute way. It is a truism that an individual dies only when the

last

person who knew and remembered him dies; that a human being finally

ceases to

exist when all the bearers of his memory depart this world. Something

like this

also happens with war. Those who went through it will never be free of

it. It

stays with them as a mental hump, a painful tumor, which even as

excellent a

surgeon as time will be unable to remove. Just listen to people who

lived

through a war when they sit down around a table of an evening. It

doesn't

matter what the first topics of conversation might be. There can be a

thousand

topics. But in the end there will be only one: reminiscences from the

war.

These people, even after years of peace, will superimpose war's images

on each

new reality, a reality with which they are unable to fully identify

because it

has to do with the present and they are possessed by the past, by the

constant

returning to what they lived through and how they managed to live

through it,

their thoughts an obsessively repeated retrospection.

But what

does it mean, to think in the images of war? It means to see everything

as

existing at maximum tension, as reeking of cruelty and dread. Because

wartime

reality is a world of extreme, Manichaean reduction, which eliminates

all

intermediate hues, all things gentle and warm, and limits everything to

an

aggressive counterpoint, to black and white, to the most primal battle

of two

powers: the good and the evil. No one else on the battlefield! Only the

good

(in other words, us) and the evil (meaning everything that stands in

our way,

that opposes us, and which we force wholesale into the sinister

category of the

enemy). The image of war is imbued with the atmosphere of force, a

nakedly

physical force, grinding, smoking, constantly exploding, always on the

attack,

a force brutally expressed in every gesture, in every strike of a boot

against

pavement, of a rifle butt against a skull. Strength, in this universe,

is the

only criterion against which everything is measured-only the strong

matter,

their shouts, their fists. Every conflict is resolved not through

compromise,

but by destroying one's opponent. And all this plays itself out in a

climate of

exaltation, fury, and frenzy, in which we feel always stunned, tense,

and

threatened. We move in a world brimming with hateful stares, clenched

jaws,

full of gestures and voices that terrify.

For a long

time I believed that this was the world, that this is what life looked

like. It

was understandable: The war years coincided with my childhood, and then

with

the beginnings of maturity, of rational thought, of consciousness. That

is why

it seemed to me that war, not peace, is the natural state. And so when

the guns

suddenly stopped, when the roar of exploding bombs could be heard no

more, when

suddenly there was silence, I was astonished. I could not fathom what

the

silence meant, what it was. I think that a grown-up confronted with

that quiet

could say: 'Hell is over. At last peace will return.' But I did not

remember

what peace was. I was too young for that; by the time the war was over,

hell

was all I knew. Months passed, and war constantly reminded us of its

presence.

I continued to live in a city reduced to rubble, I climbed over

mountains of

debris, roamed through a labyrinth of ruins. The school that I attended

had no

floors, windows, or doors-everything had gone up in flames. We had no

books or

notebooks. I still had no shoes. War as trouble, as want, as burden,

was still

very much with me. I still had no home. The return home from the front

is the

most palpable symbol of war's end. Tutti

a casal But I could not go home. My home was now on the other side

of the

border, in another country called the Soviet Union. One day, after

school, I

was playing soccer with friends in a local park. One of them plunged

into some

bushes in pursuit of the ball. There was a tremendous bang and we were

thrown

to the ground: my friend was killed by a landmine. War thus continued

to lay in

wait for us; it didn't want to surrender. It hobbled along the streets

supporting itself with wooden crutches, waving its empty shirtsleeves

in the

wind. It tortured at night those who had survived it, reminded them of

itself

in bad dreams.

But above

all war lived on within us because for five years it had shaped our

young

characters, our psyches, our outlooks. It tried to deform and destroy

them by

setting the worst examples, compelling dishonorable conduct, releasing

contemptible emotions. 'War,' wrote Boleslaw Micinski in those years,

'deforms

not only the soul of the invader, but also poisons with hatred, and

hence

deforms, the souls of those who try to oppose the invader'. And that is

why, he

added, 'I hate totalitarianism because it taught me to hate.' Yes, to

leave war

behind meant to internally cleanse oneself, and first and foremost to

cleanse

oneself of hatred. But how many made a sustained effort in that

direction? And

of those, how many succeeded? It was certainly an exhausting and long

process,

a goal that could not be achieved quickly, because the psychic and

moral wounds

were deep.

When there

is talk of the year 1945, I am irritated by the phrase, 'the joy of

victory'.

What joy? So many people perished! Millions of bodies were buried!

Thousands

lost arms and legs. Lost sight and hearing. Lost their minds. Yes, we

survived,

but at what a cost! War is proof that man as a thinking and sentient

being has

failed, disappointed himself, and suffered defeat.

When there

is talk of 1945, I remember that in the summer of that year my aunt,

who

miraculously made it through the Warsaw Uprising, brought her son,

Andrzej, to

visit us in the countryside. He was born during the uprising. Today he

is a man

in late middle-age,

and when I

look at him I think how long ago it all was! Since then, generations

have been

born in Europe who know nothing of what war is. And yet those who lived

through

it should bear witness. Bear witness in the name of those who fell next

to

them, and often on top of them; bear witness to the camps, to the

extermination

of the Jews, to the destruction of Warsaw and of Wroclaw. Is this easy?

No. We

who went through the war know how difficult it is to convey the truth

about it

to those for whom that experience is, happily, unfamiliar. We know how

language

fails us, how often we feel helpless, how the experience is, finally,

incommunicable.

And yet,

despite these difficulties and limitations, we should speak.

Because

speaking about all this does not divide, but rather unites us, allows

us to

establish threads of understanding and community. The dead admonish us.

They

bequeathed something important to us and now we must act responsibly.

To the

degree to which we are able, we should oppose everything that could

again give

rise to war, to crime, to catastrophe. Because we who lived through the

war

know how it begins, where it comes from. We know that it does not begin

only

with bombs and rockets, but with fanaticism and pride, stupidity and

contempt,

ignorance and hatred. It feeds on all that, grows on that and from

that. That

is why, just as some of us fight the pollution of the air, we should

fight the

polluting of human affairs by ignorance and hatred. D